Amanda Britton and Johanna Norry usually create work on their own, using a mix of techniques and processes. But in their collaborative project Common Thread they got together, creating work using a back and forth process of communication – a process based on trust and respect.

The two artists had known each other for a long time so they quickly grasped the potential benefits of working together. Each gained insights from the other’s work while meeting online and in the studio.

Amanda was able to incorporate weavings made by Johanna, which added an extra element of interest to her compositions. And Amanda’s experiments triggered new ideas for Johanna. This co-working experience helped to motivate them both and accelerate their progress.

When you read on, you’ll find inspiration and ideas for working with others, and discover how collaboration can elevate your art to a new level. Through a productive phase of shared activity, Johanna and Amanda were able to release feelings of protectiveness of their own work, bounce ideas off each other, and allow their work to evolve into a cohesive gathering of exhibits.

There’s more than one way to stimulate your creative ideas – and collaborative working might be just what you are looking for.

Accumulating, remembering, archiving…

Can you tell us a little about the art you make?

Amanda Britton: Utilising unconventional materials including paper, vellum, resin and plexiglass, the work I make is like intricate fabrics, ‘woven’ with a variety of techniques, colours, and constructions.

Recently I’ve been thinking a lot about the concept of migration – moving towards some things and away from others. The ways in which we shift, change and create patterns, rituals and repetition.

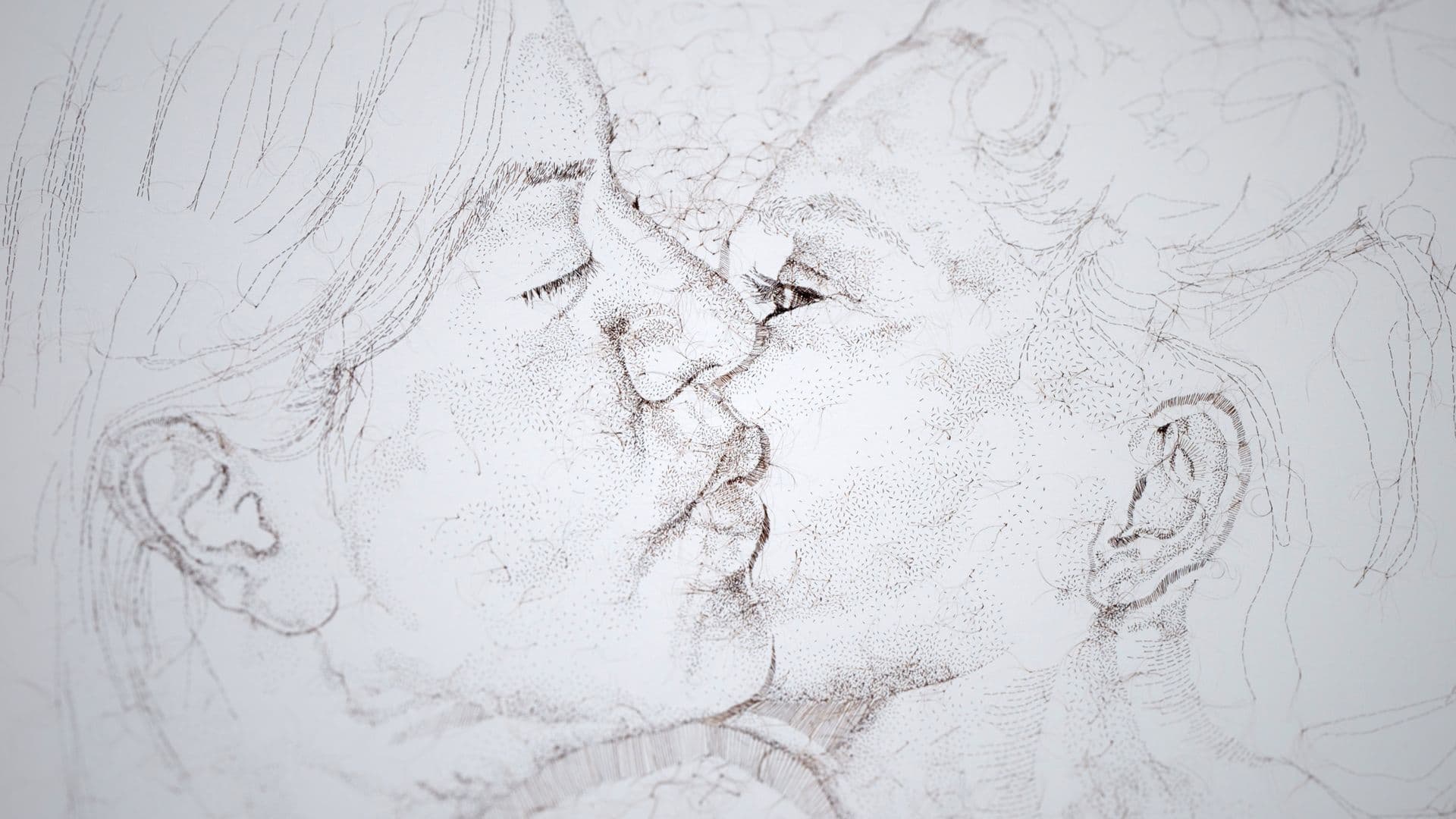

Creating intersections, remembering, and archiving the parts that are left behind, my work takes the form of sewn collages on paper, bringing together fragments of material, paper, and found objects – or casts of those objects.

I’ve always been interested in the perpetuation of relationships between people and the exploration of families, place, narrative and language. Concerned with documentation and preservation, my work is personal in concept, yet quirky and humorous in delivery.

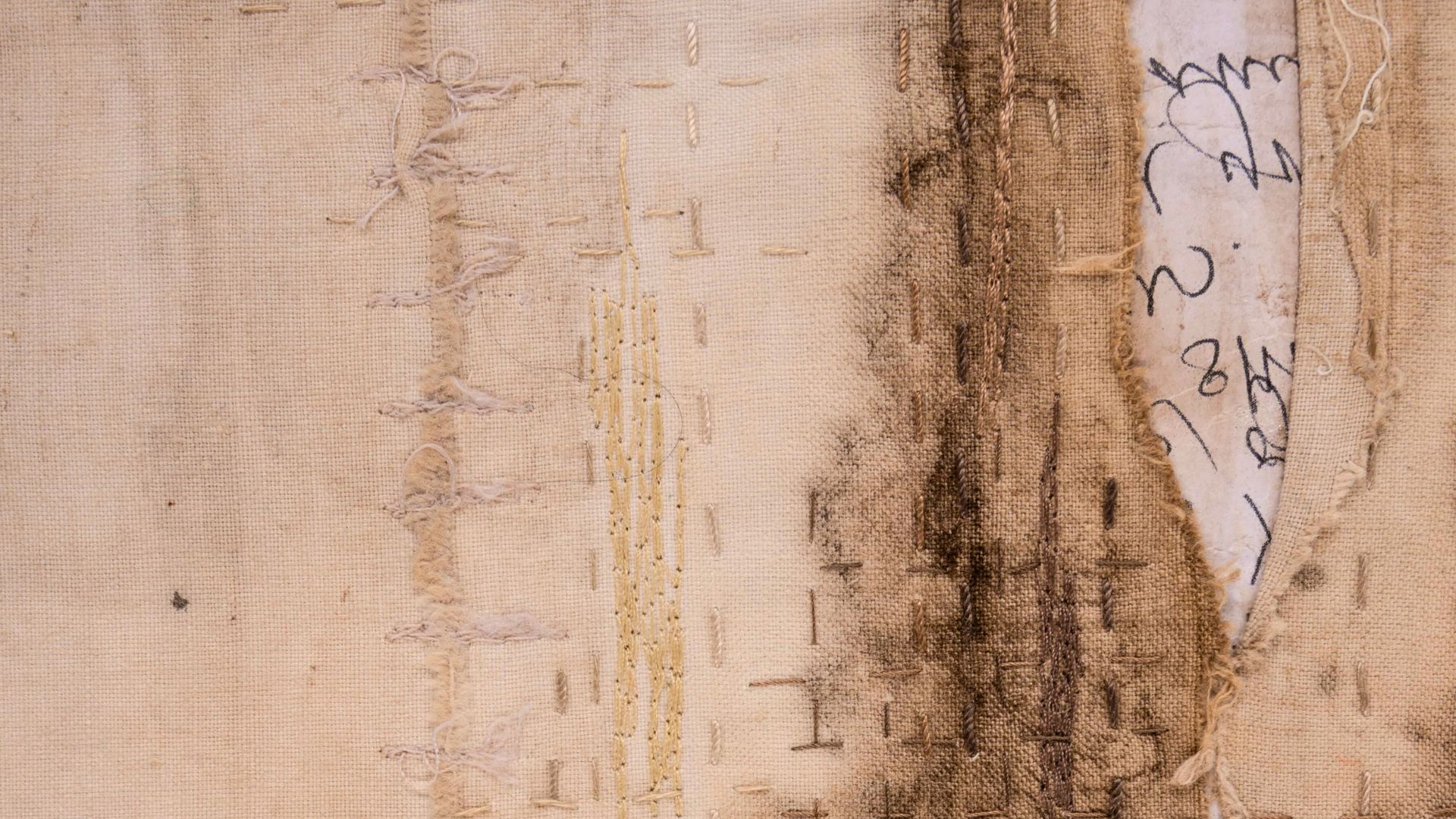

Johanna Norry: My work employs the traditional techniques of weaving, hand knitting, coiling, embroidery and stitching. Often I create work that combines comforting materials with unexpected forms. I take a similar approach when I am collaging and working with photos, whether family snaps or found images, or mining memories – working with real and metaphorical archives.

My artistic process is to respond to my research in a way that culminates with art and installations that are themselves a sort of documentation, whether an accumulation or manipulation of evidence. The resulting work might appear incomplete, and distorted, with only a fraction of the truth remaining, as revealed by my material interpretations.

I used to see my textile work and my collage work as separate. Recently, those lines began to blur. It began with appliqué textile collage and quilted portraits, and morphed into woven photos, piecing together my hand woven and hand knitted material in the same manner as I might assemble various photos and papers into a more traditional collage.

The metaphors of weaving, stitching and collage are always at the forefront of my art making thought process. My work is usually about my inner life, my identity, my values and obsessions, my connection to my family and ancestors, and I combine disparate parts as a way of illustrating how I am made up inside – different parts, different experiences and different inheritances, sometimes cohesive and sometimes incongruous.

What initially attracted you to textiles as a medium?

Amanda: My mother, Heather Britton, ignited my passion for textile art and design. I grew up falling asleep to the hum of her sewing machine – she’s a novice sewer and also worked in the carpet industry for more than 40 years.

Johanna: My husband’s mother was a textile artist and weaver, with a weaving studio in Rochester, New York. She had several weavers who came to her studio each day to weave her commissions. Sadly, she died from cancer just a few years after I met her. I inherited everything from her studio including her loom, her tools, her yarn and her notes.

I was pregnant at the time and the last thing I had time for was learning to weave. It all went into storage and I made myself a promise that I would learn to weave on the same schedule she did When my son turned five, I signed up for a weaving class. I was immediately hooked and took classes for several years.

One of my weaving teachers suggested I take a dyeing class at Georgia State University. After just a few weeks I knew that I wanted to make art and be in the textiles classroom, for the rest of my life.

While pursuing my Textiles BFA and MFA, my work expanded beyond weaving, and incorporated embroidery, knitting, digital processes, piecing and quilting, and felting. I chose the process that I thought best suited the concept I was exploring.

As an older student, others assumed that I already knew how to do all these things, but it was all new to me. The last time I’d used a sewing machine was when I got a C grade for a wraparound skirt made in my junior high home economics class.

My gravitation toward fibres wasn’t based on familiarity of technique, but rather the familiarity with fabric. We adorn our bodies and homes with fabric, and the textures, patterns and colours can elicit memories and nostalgic longing.

My work with fibre may have started with the inheritance of a loom, but I really can’t imagine any other medium being better suited for communicating my ideas about the human experience.

Long term support

Tell us more about how this collaboration came about…

Johanna: Amanda and I met in graduate school at the University of Georgia. For two years, our studios were next door to each other. It was awesome. And while I think I was subtly aware of the specialness of that time, and the luxury of devoting time to making our own work within a supportive community, I wasn’t quite prepared for how much I would miss it when I moved on.

It turned out that Amanda also missed it and, fairly soon after she graduated, we decided to meet occasionally, if not regularly, to support each other and critique each other’s work.

While our show’s name Common Thread refers to the relationship we began to observe in our current work, the truth is there was already a thread – conceptually, if not aesthetically – in our graduate school work as well.

Amanda’s work was tethered to her family memories and the ephemeral nature of memory itself, and my work was also rooted in family, in research, and unearthing hidden family secrets and exposing them to the light of day through my art.

We had both been regularly making and showing work in juried shows since graduation. But we were also both beginning to accumulate work that felt like it needed to be shown all together.

‘Our decision to work towards a show together, Common Thread, was so organic that I cannot even remember who thought of it first.’

Johanna Norry, Textile artist

Once we had decided to collaborate, it motivated both of us to flesh out work we had started, and to make more, knowing that if our proposals were accepted, we would need to do a lot of work to fill a gallery. As we were making new pieces, that’s when the collaboration conversation began – the intentional back and forth development process, responding to elements we observed in each other’s work.

Back & forth process

Tell us about the collaboration process…

Johanna: Amanda and I began to prepare for our first duo show at Berry College, Georgia, in the summer of 2023. Initially, we worked separately in our home studios, communicating by texting photos of our work to each other.

Then we organised several joint studio days where we would bring our works in progress – works we considered finished – as well as remnants, and uncommitted bits of cloth that we had created by one method or another.

Pieces migrated from my table to hers, and vice versa. For example, I had a long and narrow woven test sample, which Amanda saw with fresh eyes; she cut it in two and incorporated it in an installation of dyed organza strips that she had sewn ephemera into.

Our process was like a conversation – a back and forth. I would see something in Amanda’s work, like the way she was using family beach photos, shells and references to the migration of sea birds. I realised that I also had 1970s family photos taken at the beach that I could use, and my own collection of rocks and shells.

This led to my weaving together old family photos, pairing them with collages of woven remnants, and combining rocks and shells with off-loom wovens in plexiglass boxes, as companions to Amanda’s natural history display-inspired assemblages.

How did you achieve the collaboration, logistically?

Amanda: Thankfully, both Johanna and I live and work relatively close to one another in North Georgia. Over the summer, my university’s facilities were open and available, which allowed us a central location to meet and make. While we did call and meet online, our most productive days were those shared in the same studio space.

Our advice for anyone collaborating or wanting to initiate a collaborative project is to let it be organic. Partner with someone you respect and are excited by their work. Ask yourself if you see a connection in your work, while still being distinct from each other.

‘A collaborative connection might be the theme, process or an aesthetic. If there’s a connection between you, that you think others could see as well, then that’s a good place to start.’

Amanda Britton, Textile artist

While it was awesome that we could meet and work together in the studio, it would equally be possible to collaborate with someone in another city, thanks to Zoom and ease of sharing virtually.

Evolution & unification

Did the project’s exhibition feel as cohesive as you hoped?

Amanda: We had a lot of wonderful feedback from both students and staff at Berry College. The work covers so many different techniques, mediums and interests, including photography, textiles, sculpture and installation, yet it was unified by colour and archiving concepts.

We wanted to push the visuals and create an unexpected viewer experience. I think we captured this with scale variations and colour juxtaposition of the work.

However, and I think Johanna would agree with me, as soon as the exhibition went up we knew the work would likely shift and evolve as it travelled to its next location. Edits and considerations have been vital throughout.

How did you help your audience understand the connections built through the collaboration?

Amanda: Johanna and I are very intentional about the layout of our travelling exhibition. Not only have we considered the space of each gallery (the Moon Gallery at Berry College is expansive with low ceilings, whereas Westobou is a tight space with high ceilings), but we are also interested in conceptualising new or alternative display methods.

Like paintings, textile works tend to be displayed in very traditional ways and we knew we wanted to activate the space differently. Whether hanging woven pieces high and then paper collages low, we are intentionally and thoughtfully curating the works by colour, technique and concurring themes.

Also in this duo display, we’re not concerned with labelling every piece with its maker and materials – we like the idea of just letting the viewer experience the work as a unified whole.

Did you have any previous experience that helped prepare you for working on a duo project?

Johanna: In graduate school, Amanda and I, along with another textile artist and two ceramic artists, collaborated on a show called Undermined. The collaboration involved the ceramic artists making work, primarily functional objects, but also more sculptural and figurative work, then the three textile artists set about undermining the functionality of the objects.

We bound plates together with thread, which included my knitted tubes that connected the cups to each other, and a web of screen printed silk organza created by Amanda.

Undermined was my first experience of collaboration as a sort of call and response process. The Common Thread collaboration was similar, but the conversation was more of a repeated back and forth process, rather than a simple call and response.

Other group shows I’d been in were different, in that I was invited because my work was perceived as fitting into an already existing concept. The artworks in those shows were pieces I had already made and had not been created in such a conversational way.

The benefits of collaboration

Could you choose one particular favourite artwork and share how the collaborative process improved it?

Amanda: Carapace Capsules is one of my favourite collaborative pieces in the show. The piece is small in scale but allows for an intimacy with the work.

Both Johanna and I are very interested in the concept of the archive: questioning what is collected and what memories are retained through these mementoes. These transparent boxes and trays felt like precious time capsules that combine both of our unique perspectives.

Johanna: Possibly my favourite collaboration of the exhibit relates to how we installed our work together, and how we viewed our work in relation to each other’s art.

We decided to install Amanda’s work Hereditary Smoker Series, a pair of plexi-trapped textiles and digitally printed vellum, next to my work Sapelo Dreams: Asleep in a Live Oak, a long clasp-woven cloth and a pair of woven collages I made from weavings on hand-painted warps.

I would never have installed these collages on their own in this way, higher and lower than usual. But it was all about the interaction of the work – we invited the viewer to see my work through Amanda’s work, which was mounted on hinges perpendicular to the wall.

Amanda’s work was about her grandmother, and my pieces were about my own family memories of places (Sapelo Island, a favourite family camping spot) and about our lives as a process of repair, piecing ourselves (back) together from a combination of inheritances and experiences.

I think both our works were elevated by their proximity and how they interacted with each other.

What were the main benefits of collaborating and would you do it again (with other artists or with each other)?

Amanda: Since this experience, I’ve been more receptive to both working with others and using techniques, processes and mediums that I’m not as familiar with. For instance, I am in the beginning stages of a collaborative project with a local sculptor for an outdoor sculpture installation. Without this experience with Johanna, I wouldn’t have been as easily persuaded to join in on this opportunity.

Johanna: I’d collaborate again, most definitely. And I’m thinking of including a collaboration project in my textiles course next semester. I’d love to give my students an opportunity to experience the impact of working with another artist and the effect it can have on the direction of their work.

Do you have any tips for readers wanting to set up their own collaborative project?

Johanna: My advice would be to begin with trust. I already knew and trusted Amanda. I knew that while our processes were not the same, that they were compatible. A collaboration could be successful with two artists who were previously strangers, but you can’t go into a collaboration with a fear of the other artist stealing your ideas or accusing you of stealing theirs.

‘If you begin with respect, trust, and a commitment to honour each other in the work that comes out of the collaboration, I think it will be a positive experience and it will result in elevating both artists’ work.’

Johanna Norry, Textile artist

Amanda and I have a show coming up in 2025 where the curator has paired us with another duo of textile artists who know each other, but we don’t know them or their processes, and I am hopeful it will be successful and an uplifting experience.

Amanda: Setting and sticking to a timeline would be my biggest tip – deadlines for a show or an upcoming application can help with the planning of your timeline.

Also, it’s handy for both contributors to be working on a similar scale or technique. For example, Johanna and I both knew we wanted to create long narrow pieces to have as a visual mirroring effect.

When she suggested creating an eight foot woven assemblage Sometimes, It Just Fits, that allowed a direction for my nine foot collection display A Sea of Sinister Dots. These pieces were displayed across the gallery from each other, and I love the effect of the scale and central placement.

How has the collaboration affected your own art practice?

Amanda: Before this experience, I would say I was closed off to the idea of collaboration.

I am very goal-oriented and independently motivated, however, this experience has allowed me to see how collaboration is important for growth – not only as a person but to allow one’s art to grow as well.

It is amazing to have a partner to bounce around ideas for colours, techniques and concepts with.

Johanna: I’ve always sought feedback. Whenever I make something, at the very least my husband gets called in to look at it, and I value his response.

But I’ve also felt possessive about what I’ve made – or perhaps protective is a better word. Like I had some sort of parental responsibility to defend my art, since I had made it.

I think the collaborative, sharing process – where things I’ve made have been incorporated into Amanda’s work, and things she’s made have gone into mine – has expanded my emotional attachment to my artworks. I feel more accepting of what they become once they’re made.

Comments