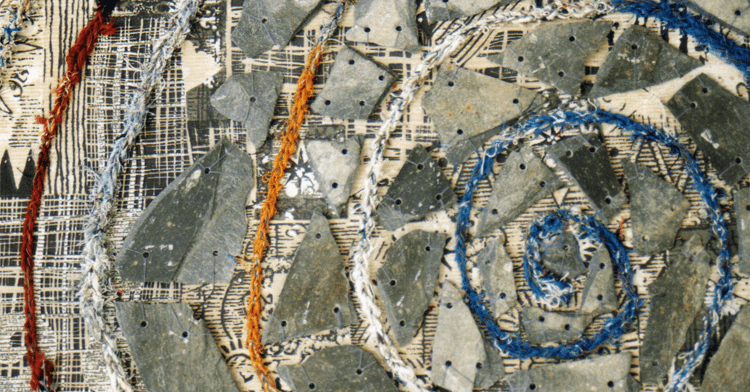

Sue Hotchkis’s textile art is proudly contrarian. In a world that worships youth and the latest new thing, Sue celebrates all things falling down and falling apart. She captures the beauty only true relics can bear, glorifying all their bumps, scrapes, missing parts and other forms of neglect.

You’d think pursuit of the decrepit would lead to sombre tones and overall sadness in her work. But Sue’s 3D ‘fragments’ remind us to look for the overlooked and discover their treasures of colour, pattern and texture. There’s a joyfulness that Sue presents that’s both engaging and remarkable.

Sue’s creative process is also as textured and dimensional as the ageing process she presents. Each work features a mashup of photography, dyeing, print, fabric manipulation and embroidery. And we’re grateful to Sue for sharing many of her insider tips related to each of those techniques.

Welcome to Sue’s world that celebrates the lost and forgotten. It’s simply gorgeous.

Fragile fragments

Sue Hotchkis: I call my abstract works ‘fragments’ because they capture the fragile, transient beauty of things ageing and decaying. When nature breaks things down in urban or rural places, it’s a slow process. Holes and layers are created that reveal long-forgotten hidden surfaces or paint colours. A cracked edge of rusted metal becomes lace-like.

I love finding new patterns and shapes that are different and original. I also get excited using my camera to zoom in on the details and imagine how I can use them in my work.

To me, all that decay looks like miniature works of art. And I try to infuse that same broken quality into my work.

I also try to blur the boundary between a picture and an object. Playing with the shape and form makes my art feel as though it was once a part of something that existed versus making a 2D image that’s more like a photograph or picture.

Intuition leads the way

I work organically and respond to what develops. I enjoy trusting accident and chance when manipulating and experimenting with fabrics. And I relish finding new ways to create marks on surfaces.

I don’t use commercially printed fabrics. Very occasionally I might find one with an interesting texture, but then I’ll work into it to the point it becomes unrecognisable. I prefer to create every aspect of my work, although having a limited amount of handmade fabric can result in me running out. Still, I enjoy the problem-solving aspect of all that. So, I never throw anything away, no matter how small. The bit that got chopped off today may well be the bit I need later.

One of my must-haves is a wall space on which I can pin a work during the creative process. It’s important to be able to stand back and view the work from a distance. Every one of my works finds me piecing together parts which I add and remove along the way. As a result, a single piece can take anywhere from a week to several months to fully evolve.

Seeking decay

I’m passionate about surface and texture, and I’m drawn to the insignificant and overlooked. I look for things that have been damaged in some way by human touch, neglect or the weather. Cracked plaster, crumbling paint, torn posters, or broken metal from oxidation are all interesting to me.

I find what I’m looking for mainly when travelling, often on trains, in stations, harbours or the high street. It can be found on walls and pavements and derelict buildings. I look for patterns, shapes and colour combinations within those damaged surfaces to use in my work.

I then take photographs with either a traditional camera or my iPhone which is handy if I’m out and about. I can edit and play around with an image whilst on the move. My actual camera has a long zoom which helps me close in on a detail, and it takes quality high-resolution images that I can accurately crop.

I don’t work directly into a sketchbook, because I get distracted trying to make it become a beautiful work of art. I prefer to work directly with my photographs and on loose paper and prints from computer images. I use Photoshop to turn my photographs into black and white images that can be used to make a thermofax or silk screen.

I do have a few ‘favourite’ sets of images that I’ve used a lot in my work. One is a collection of photos I took of a rusty old fishing boat in Iceland way back in 2007. It has inspired several works, most recently Avast (2022). I also adore the images I took at a Heritage Railway’s repair yard that was filled with bits of old trains. It was before digital cameras took off, so I only have a couple of images. But they continue to provide inspiration.

Dyeing and printing

I took a print workshop during my embroidery degree, and then, during my master’s degree, my tutor pushed me out of my comfort zone by having me focus on using print rather than stitch. It was definitely a challenge, but I’m glad I accepted. I’ve enjoyed combining the two techniques ever since. For me, they go hand in hand, and the print enhances the stitching.

I usually work with any plain white medium-weight cotton, as long as it is 100 per cent cotton and takes the dye. I also use synthetic fabrics such as voile and felt.

I create thermofax screens (like a silk screen) from my images for printing. I then use either a procion dye mixed with Manutex or a ready-mixed textile printing medium. Procion dyes take longer to prepare and fix, whereas ready-made textile printing mediums are immediate and can be heat set. Procion dye fully colours a cloth, while textile medium just sits on top of the fabric, making the handle much stiffer. For each work, I weigh the pros and cons, and sometimes I’ll use both types on one cloth.

I also use a discharge paste to remove dye, taking the fabric back to its original colour before printing. Depending on the paste’s strength, dye removal varies which can lead to variations in colour. The paste is clear, and you don’t see its effect until heat and steam are applied. I enjoy that element of surprise.

Bring on the heat

Fabric manipulation plays a strong role in how I create my work. That includes using stitch, padding and quilting to distort a shape.

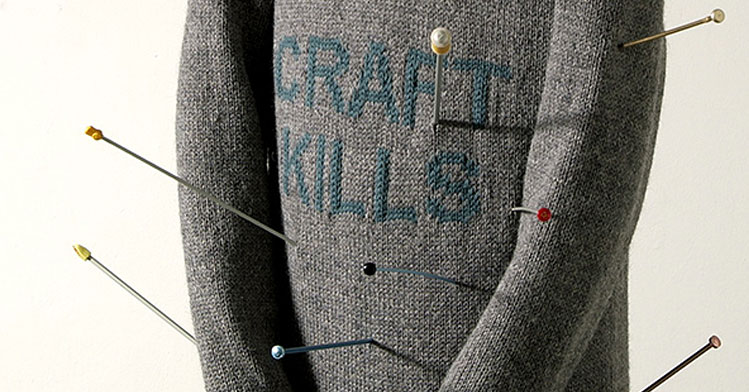

But I’m not too precious about my artwork, so I also chop or rip larger pieces of fabric, as well as use a heat gun.

I learned most of my techniques during my embroidery degree, but I explored using a heat gun on my own. My mum gifted me one, and I found it a great way to create holes and broken edges with synthetic fabrics. I stitch on the fabric first and then use the heat gun to manipulate it further, as melted fabrics often become too hard to stitch.

I wear a mask when using the heat gun, and I make sure the room is well ventilated to protect against nasty fumes. I only use the gun in short bursts, as once a fabric is melted, there’s no going back.

I had tried using a soldering iron in the past, but I struggled to completely clean the tip, so the unpleasant fumes from melted fabric would linger until the iron cooled down. I also managed to burn myself, so I gave up on that tool.

Free-motion tips

Embroidery is on my mind throughout my creative process. I stitch onto fabric at the beginning of a project, as well as once it’s been printed and quite often again whilst the piece is being made.

I look at the patterns and marks on my images and think about how they can be translated into computerised stitching or how I could use free-motion stitch. I’ll build up a collection of printed and stitched fabrics that I can use, sometimes deconstructing them as I create the final piece.

I prefer working with a sewing machine, particularly one that can drop the feed dogs for free-motion stitching. I had to replace my old Bernina 1001 after 20 years of constant use, but I replaced it with a similar model (the 1008). I still have my computerised Bernina 730E. I use it a lot, but I haven’t fully explored everything it can do. There’s always something I’d rather do than read the enormous online manual!

My best free-motion embroidery tip is to bring the bottom thread up through the fabric before starting to stitch. Then take a couple of stitches, and snip off both threads. Leaving a long thread underneath leads to tangles and knots that can break a needle. It also leaves a tidier back.

I also suggest changing needles frequently, because a blunt needle can cause lots of problems. And use the best thread you can afford. Cheaper threads can be coarse and have tiny slubs that can cause more knotting that leads to thread and needle breakages.

Lastly, always use a presser foot. I find the open darning foot works best. Never use the needle on its own, as it’s too dangerous and can damage the machine.

A later start

As a child, I was constantly making things, and my parents encouraged me with endless supplies of paint and glue. My father was a skilled carpenter, and my grandfather was a painter. Although I never met my grandfather, I was fascinated by the marks and textures in the few oil paintings my father kept. I’d try to reproduce them in my own basic oil paintings.

My mother and grandmother were always knitting and sewing, so as a child, I was surrounded by fabric and suchlike. I had my first sewing machine at seven years old and used it to make my own dolls’ clothes.

When I was in middle school, ‘Art and Needlework’ was my favourite subject, but it wasn’t until I did a foundation course at Manchester Metropolitan University that I discovered how much I enjoyed combining the two. I was 28 at the time, and as an older student, I loved every minute of it. I then went on to complete an MA in Textiles at the same university.

When I was in middle school, ‘Art and Needlework’ was my favourite subject, but it wasn’t until I did a foundation course that I discovered how much I enjoyed combining the two. I was 28 at the time, and as an older student, I loved every minute of it. I then went on to complete a degree in embroidery and an MA in Textiles at Manchester Metropolitan University.

My greatest challenge then and now is writing. I struggled with spelling and essays throughout all my education. But it wasn’t until an adult friend training as a dyslexia teacher asked to practise with me that I discovered I had dyslexia.

Fortunately, word processors were available when I wrote my dissertation, and today, predictive text and autocorrect help me enormously. I also find dictating to Microsoft Word is a great help, although it doesn’t always type what I say (while writing this, it wrote ‘banana’ instead of ‘Bernina!’).

Technology has been a lifesaver, but I do hate having to write an artist’s statement or interview. I know these things are important, but it’s hard. I wouldn’t change being dyslexic, though, as it’s part of what makes me so creative. It allows me to see the world differently.

1 comment

Sarahjane

This is a great interview. I can totally appreciate the alure of the old and decaying. The aging process is fascinating. I too take photos of everything while I’m out and about of weather beaten, surfaces and work them into my creative processes.

Thankyou