Limitless. That’s how so many artists describe the creative medium of textiles. Time and time again they explain that the possibilities are never-ending, and so very exciting.

Take Debbie Smyth, Lisa Kokin, Rosie James, Inge Jacobsen and Lindsey Gradolph, who have all found unique and personal ways to express their ideas.

These makers are constantly experimenting and advancing their craft. Some are well versed in traditional techniques and materials, others are new to textiles.

But what they all have in common is a curiosity to look beyond what’s expected. Each plays with the medium in order to tell a personal story, create a striking image, interpret feelings or to comment on the world around them.

We asked each of these contemporary textile artists about one of their artworks and to reveal the ideas that shaped it.

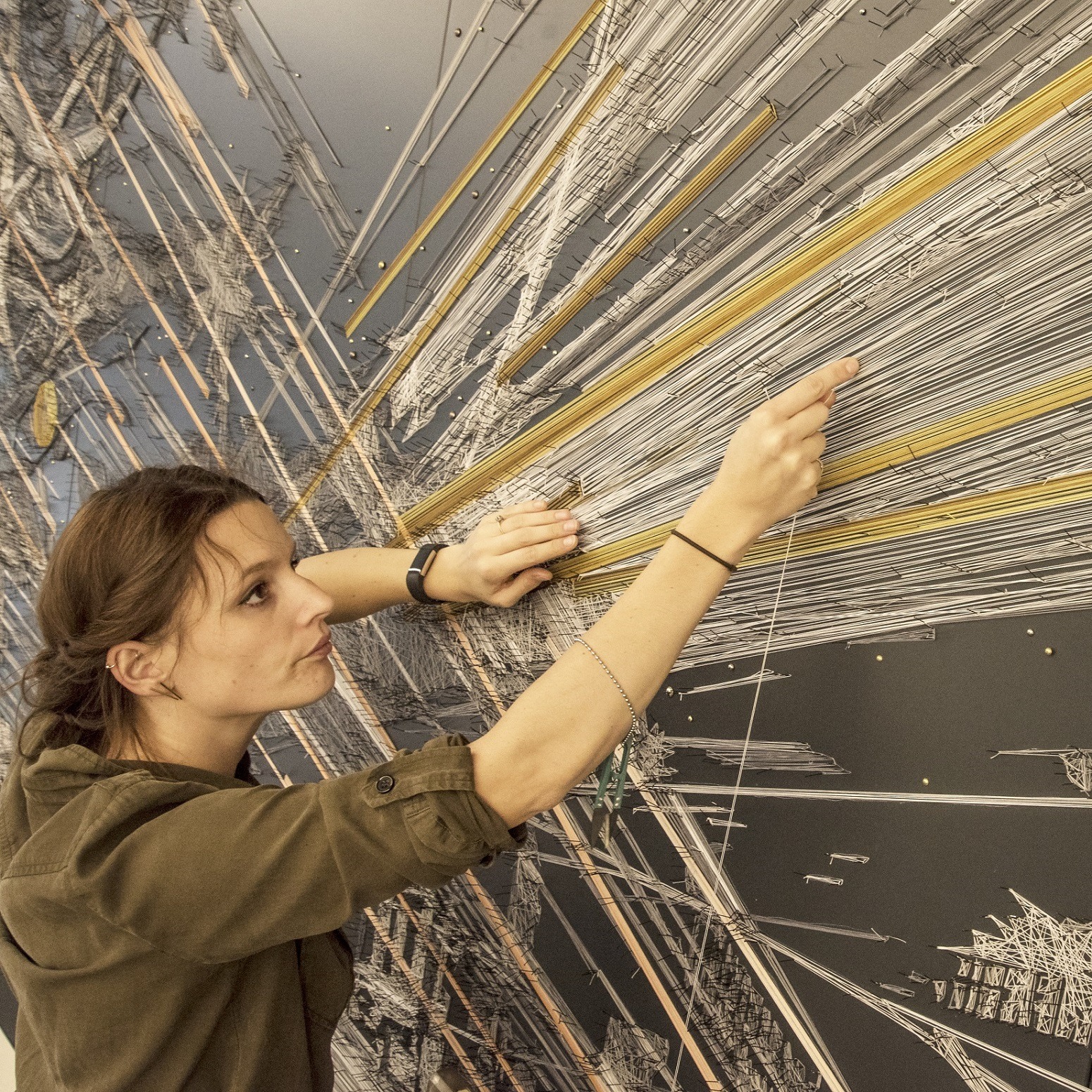

Debbie Smyth

‘Drawing is the foundation of what I do and you can draw with any materials.’ It’s a bold statement but one Debbie Smyth, who’s known for her statement thread drawings is definitely qualified to make.

Tensioned threads are stretched between precisely plotted points. Up close, you find your vision overwhelmed by a cluster of colliding, hanging threads strung amid a constellation of dressmaker’s pins, each hammered directly into the wall. Step back and suddenly the entire canvas comes into focus.

The result is a powerful, dynamic image that’s full of movement. Yet there’s not a stitch in sight.

Debbie, who’s known for her monumental, statement thread drawings, likes to blur the boundaries between the disciplines of drawing and textiles.

Using thread allows Debbie to ‘draw in space’, transforming 2D lines and planes into 3D shapes and spaces. It’s a process that results in floating, linear thread structures.

Her practice is about pushing the limits of her materials and making the ordinary, extraordinary. Take her FOLIO X FUBON series, made during a three-month residency in Taiwan.

‘I really was just desperate for an avenue to express myself… I’m always trying to create a visual landscape and record of my inner thoughts and ideas. I have never been adept at expressing myself with language. Abstract imagery combined with the thoughtful slowness of embroidery has been a lucky discovery for me.’

The idea of freely stitching in this way helped Lindsey to develop her own personal form of expressive, stitch vocabulary.

‘I’m an excellent over-thinker in all areas of my life, but my embroidery is the one place where I don’t feel compelled to do so. Whatever comes out, comes out. Sometimes it’s good, sometimes it’s only ok, and sometimes it’s pretty ugly. I just keep going.’

Choosing to work with discarded or unused and unloved textiles was also a positive choice for Lindsey, as is embroidering with fine, machine weight or button thread, handy for creating detailed repetitive patterns. For this artist, it’s the perfect combination of her aesthetic tastes and personal values.

But what most excites her is that this way of working always results in the unexpected. She never draws or makes a plan before starting a piece, and never unpicks her work.

The goal is to try to capture a feeling or an idea through her freestyle stitching.

Up close and personal

‘Basically, my work has been just an exercise in throwing my hands up, thinking to myself “whaddya gonna do?”, and then just keeping going.’

And her advice to others is similarly succinct. ‘Don’t worry so much. Just show up, get started. Make what you want to see more of in the world.’

Lindsey Gradolph (Lindzeanne) is a self-taught embroidery artist and English teacher based in Tokyo, Japan. Her work is inspired by traditional Japanese textile traditions such as Sashiko and Indigo dying, and also the concept of Mottainai or ‘waste nothing’.

Website: lindzeanne.com

Instagram: @lindzeanne

‘The machismo and violence were so overt, and over the top, that they begged to be rearranged and recontextualised.’

The medium is the message

The series was stitched in 2008, at the end of the Bush Administration, a time when Lisa hoped the cowboy mentality would soon ‘be left in the dust’. ‘How wrong I was! I continued to use the cowboy novels to comment on guns and the violence that is prevalent in our culture, and I make them now as commissions when asked.’

Trees and the natural environment were another influence since Lisa’s move to her current base in El Sobrante, a semi-rural area in California.

‘It adds a layer of richness because of the fragments of imagery and text, and also the unexpectedness of book parts being stitched into horticultural forms. I also like the symmetrical, conceptual element of tree to paper to book, and back to the image of tree and leaves.’

‘I love the fragments of imagery that occur, the inadvertent compositions that result from randomly cutting out the leaf shapes from the book covers. I make dozens of leaves and then start to arrange them by colour and shape until I have an arrangement that works. If I have to make more I do, until I’ve made enough to create a composition that works colour- and form-wise.

For Lisa, it’s an exciting approach that can bring huge rewards for anyone working with textiles creatively. ‘I would suggest that you regard materials that you encounter in everyday life as potential art supplies, not limiting yourself to what can traditionally be found in stores or online.’

Lisa Kokin’s work is in numerous public and private collections, including the Boise Art Museum, the Buchenwald Memorial, the di Rosa Preserve, Mills College, Kaiser Permanente San Francisco, Yale University Art Museum, and Tiffany & Co. She has received multiple awards and commissions in her four-decade long career. Lisa currently maintains a thriving teaching and mentoring practice.

Website: www.lisakokin.com

Instagram: @lisakokin

Inge Jacobsen

Centuries ago, the value of embroidery and lace lay not only in the time consuming and skilled nature of their production but in their exclusivity and signalling of status, as any portrait of Elizabeth I or Henry VIII reveals.

Today, mass-produced images infiltrate our every waking moment. They’re available for instant consumption, to be scrolled and liked, shared or forgotten, each quickly replaced by another in an instant.

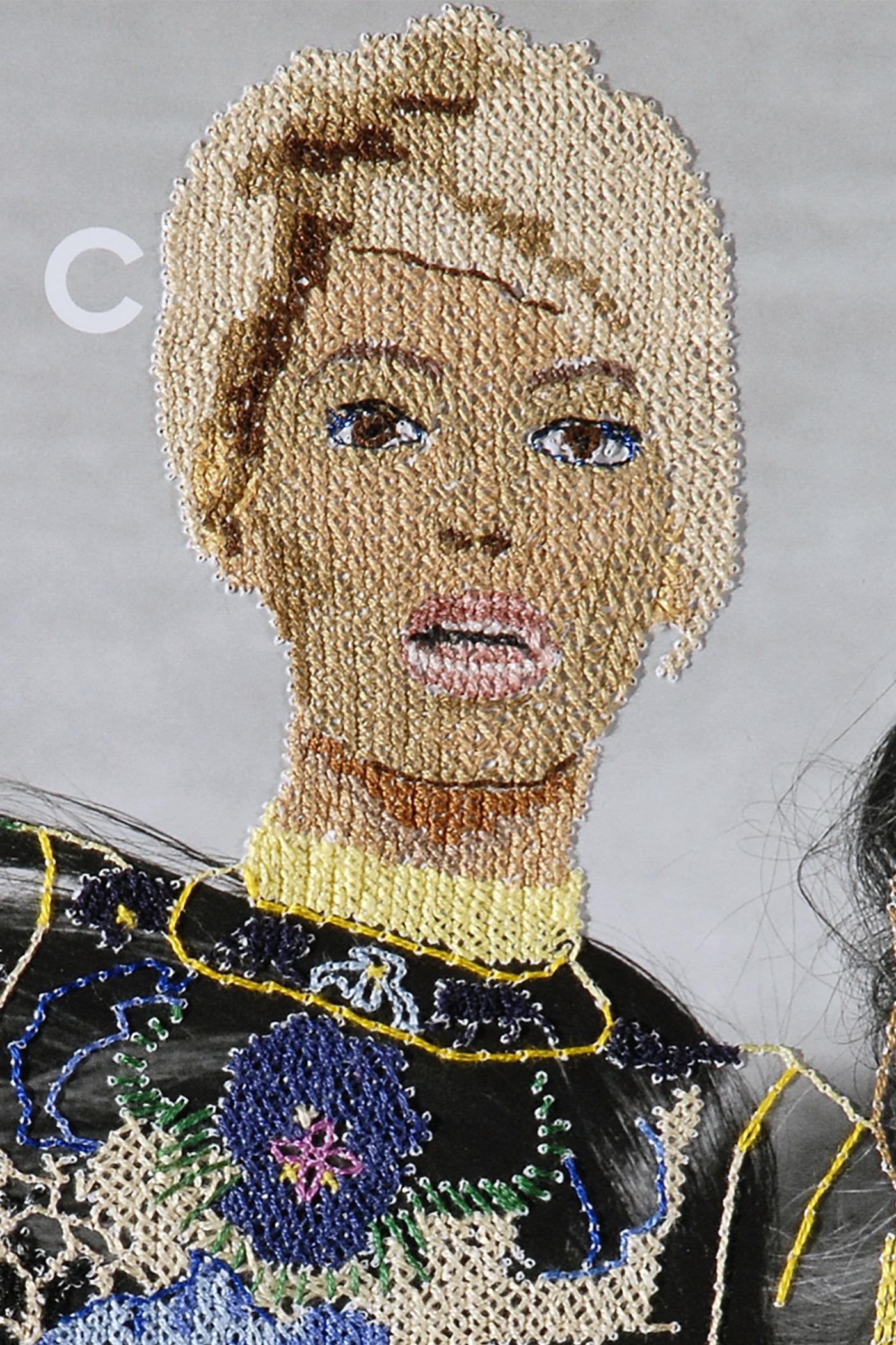

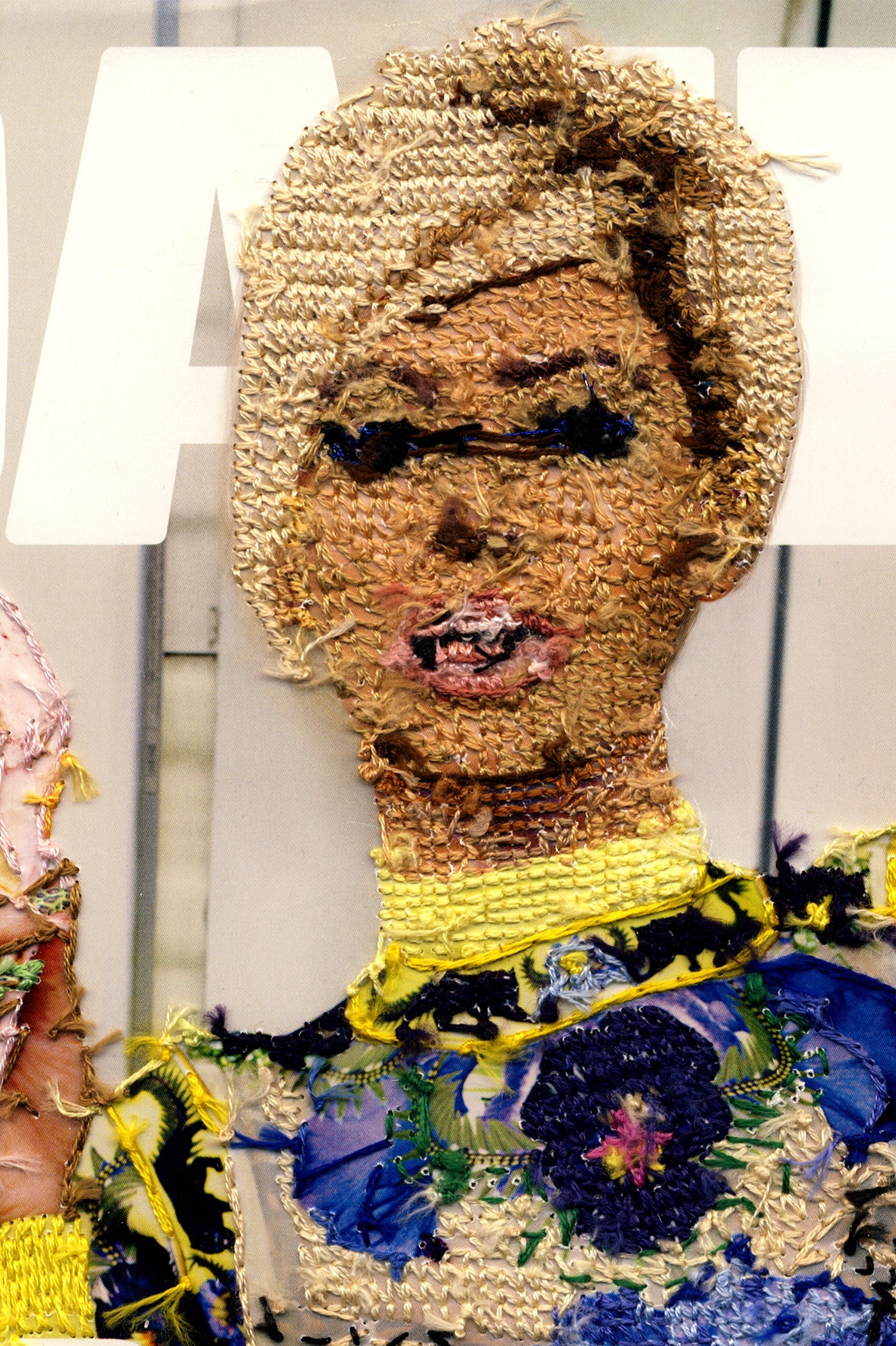

So when Inge Jacobsen chooses to spend hours embroidering a magazine cover, an obsession that results in works such as Beyoncé – Dazed & Confused – Hijacked, the result is something of a conundrum.

Obscuring the cover star’s carefully selected outfit, her perfectly styled hair and make-up are thousands of meticulously hand embroidered cross-stitches, forming a pixelated yet recognisable facsimile of the singer.

And in a further twist, the cover is stitched from the back: ‘It was such a good image and outfit, I didn’t think embroidery would improve it, so I decided to disrupt it by inverting it,’ says Inge.

Beyond the surface

While the overall image is retained it is simplified. The embroidery is still an embellishment of sorts, yet it’s a playful subversion around the conventions of worth assigned to labour and materials.

‘Why would anyone in their right mind spend hours and hours carefully embroidering something that could melt if it gets wet or tear if you pull the thread too hard, right?’ It’s a question that Inge loves to consider.

‘I love working on magazines because for most people, once they’re read or looked at a few times they become disposable – more mass-produced artwork for the trash heap, so adding time consuming embroidery adds a certain uniqueness that’s lost in the mass-production process.’

‘It goes back to the idea of making something mass-produced unique, beautiful, delicate and special. I could embroider the same cover 50 times and each one would be unique.’

For Inge, the aim is to push beyond what’s expected. ‘You can do a lot with a needle and thread – physically and conceptually. I love appropriating images versus creating an image from scratch. There is nothing wrong with a bit of creative collaboration.’

Inge Jacobsen was born in Galway, Ireland where she currently resides. She attended Kingston University, London, graduating in 2011 with a BA in Fine Art Photography and has worked as a professional artist with brands such as Apple TV and WIRED magazine UK.

Website: www.ingejacobsen.com

Facebook: www.facebook.com/IngeJacobsenArtist

Instagram: @ingejacobsen

Rosie James

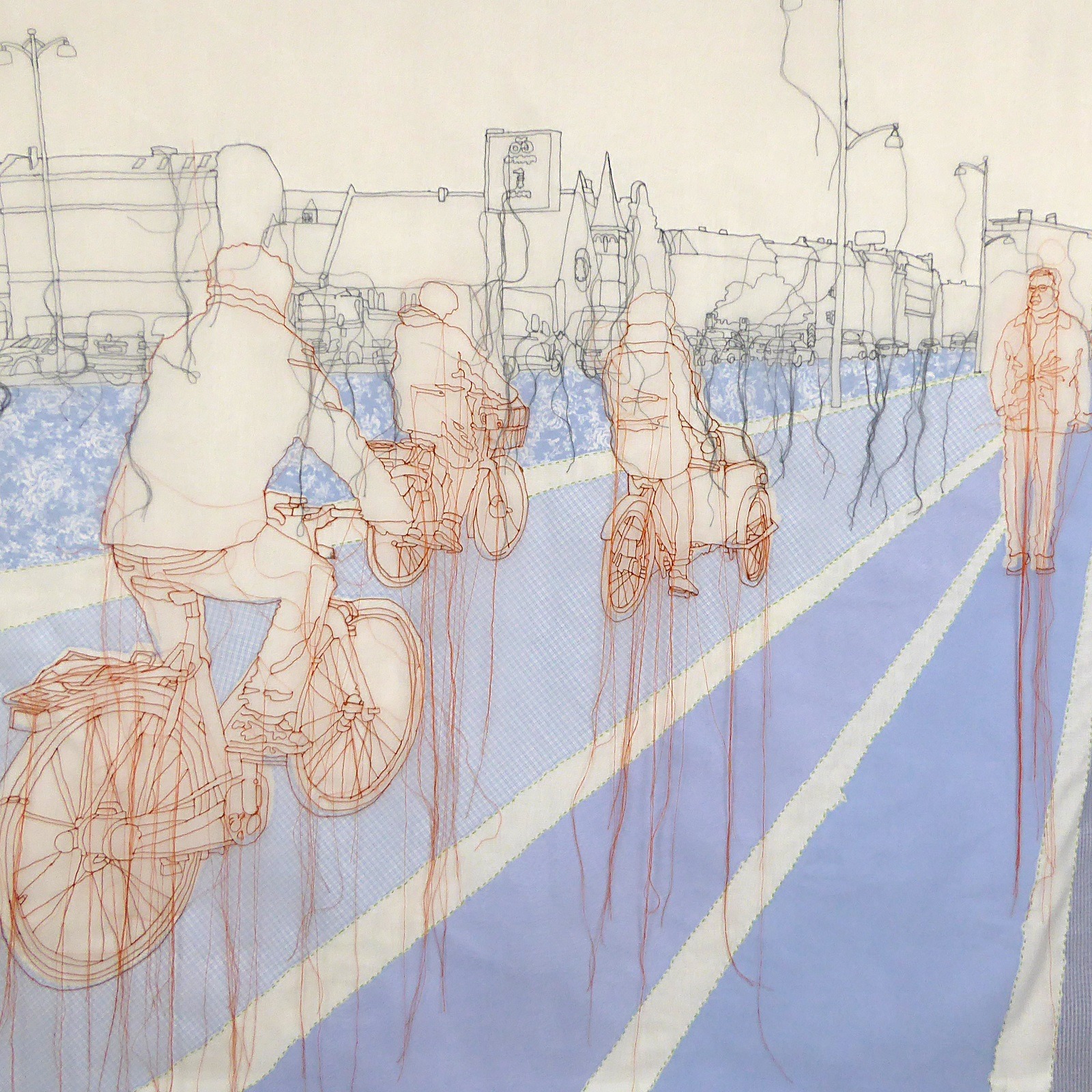

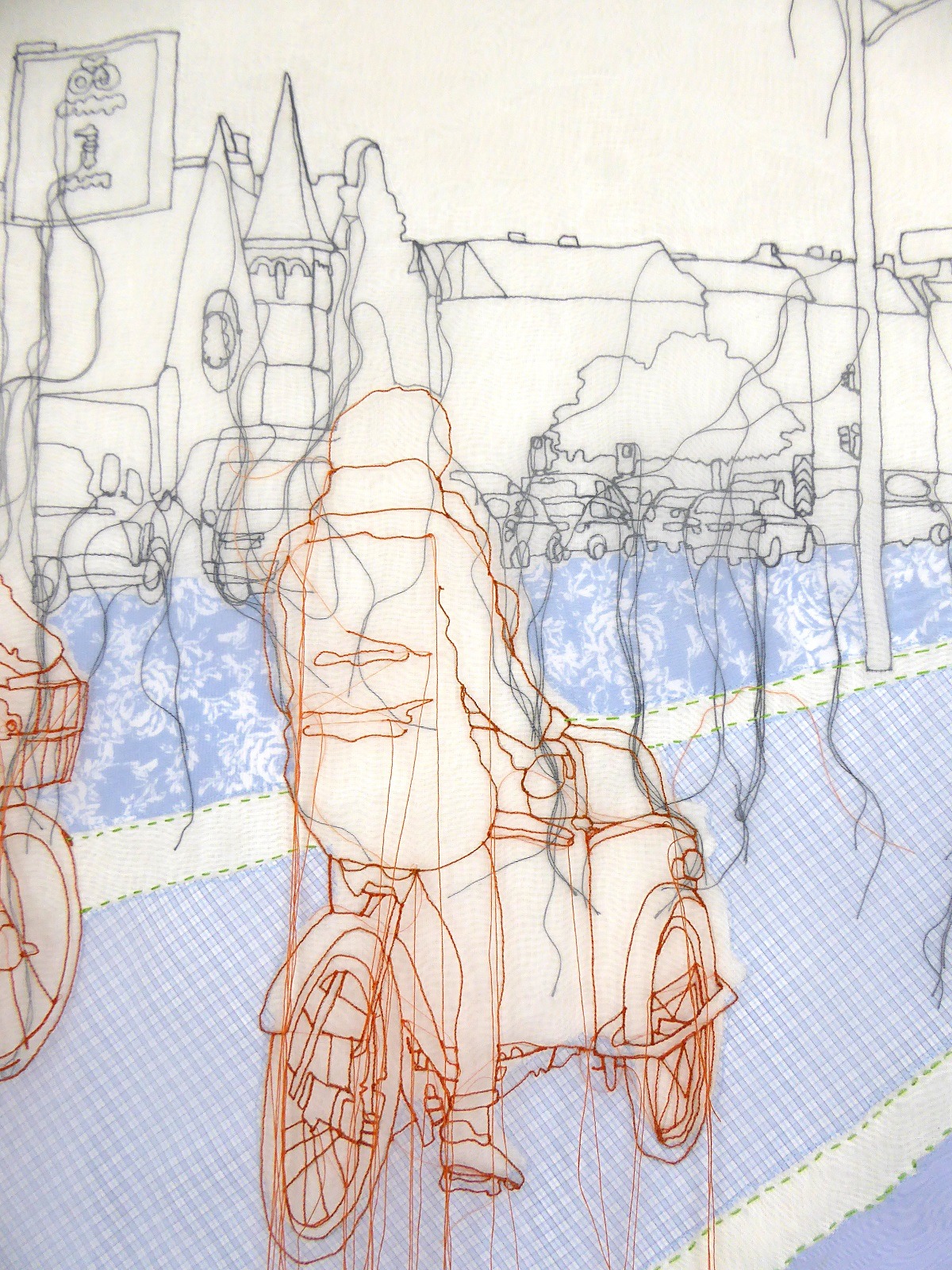

‘I love seeing how the stitched version of a photo will turn out,’ says Rosie James. ‘I think that the sewing machine has some say on what comes out the other end; you never quite know… But mostly I think I love the possibilities: there are so many different ways of working in this way and so many ideas to explore.’

Rosie James likes to use her sewing machine as a drawing tool, and photography as her inspiration. Her machine-stitched works are usually figurative, and composition is always a key element, something she’s intuitively drawn to.

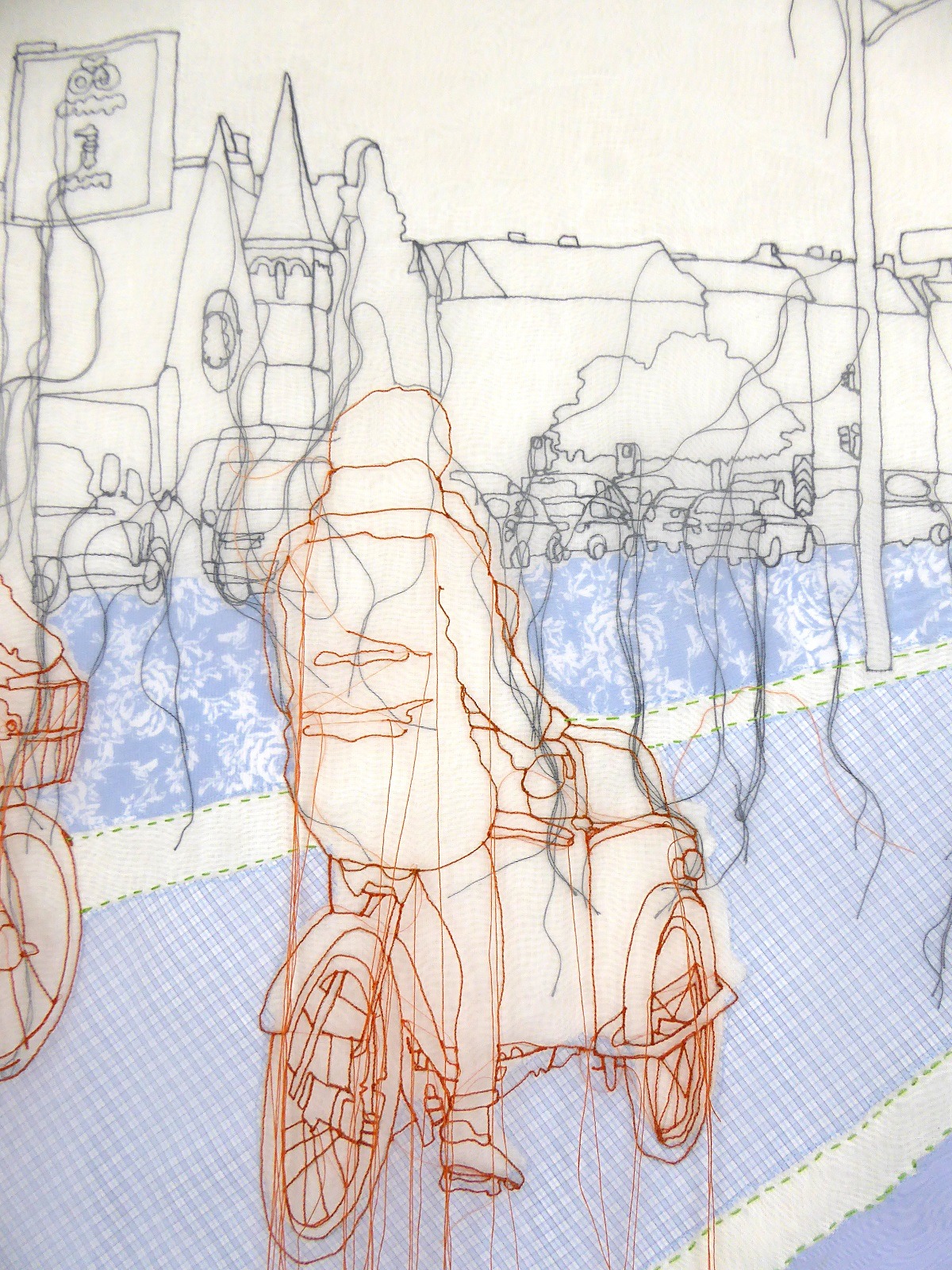

Take Rosie’s artwork Copenhagen Streetlife, a textile hanging based on a photograph snapped in Copenhagen. Three cyclists pedal away from us, while a man strolls towards us – both elements are balanced on a long diagonal axis – a road that sweeps from the foreground into the distance.

Composed of two fabric layers, contrasting coloured stitched lines differentiate between the architecture (stitched in black on the base layer) and the figures (in orange on the top sheer layer). The ‘road’, made from blue shirting fabric is sandwiched between the layers, which are stitched together in green running stitch.

But there’s something else. The original photograph pictured the scene after a recent downpour; Rosie has used loose dangling threads to give the surface ‘a rainy feel’, as if the coloured threads are actually dripping from the surface.

It’s raining thread

‘I started out by having a go at free machine embroidery and realised the possibilities immediately as a form of drawing,’ says Rosie. ‘I think it achieves a different kind of line. It’s reliant on the machine, which creates a continual line. It’s a more flowing line and lends itself to the way I like to draw, which is a kind of contour drawing.’

Even though Rosie primarily works with two materials – thread and cloth – she’s adamant that the possibilities are endless.

‘Within those two things there are so many varieties… Thread can be anything from thick cord to very fine hair, it doesn’t have to be thread as such. What else could it be?’

And she regards her materials with the same curiosity. Any surface – ‘paper, card, plastic, whatever you have lying around’ is ripe for experimentation on her sewing machine. ‘Experiment,’ she says. ‘Also consider the loose threads: change the length, the colour of them, where they go, attach them, pull them straight. Consider all the possibilities.’

Rosie James is based near Rochester in Kent in the UK. She is the author of Stitch Draw: Design and technique for figurative stitching, and a member of Art Textiles: Made in Britain.

Website: www.rosiejames.com

Instagram: @rosiejamestextileartist

Lindzeanne

Eddies of white stitches swell into circular whirlpools, nudging up against thick, broad brushstrokes of thread and thousands of tiny stabs of cotton. Lindsey Gradolph’s stitch palette may be an economical mix of back, seed and blanket stitches, but she lets them meander over the entire surface of her cloth.

A kind of pattern emerges but it’s hard to pin down. There are hints of sashiko in the work, yet there’s none of the orderliness of the technique’s uniform lines of running stitch.

Lindsey (who goes by the online name Lindzeanne) lives and works in Japan. That’s where she developed her method of expressive hand stitching, which was actually born out of creative frustration.

‘I really was just desperate for an avenue to express myself… I’m always trying to create a visual landscape and record of my inner thoughts and ideas. I have never been adept at expressing myself with language. Abstract imagery combined with the thoughtful slowness of embroidery has been a lucky discovery for me.’

The idea of freely stitching in this way helped Lindsey to develop her own personal form of expressive, stitch vocabulary.

‘I’m an excellent over-thinker in all areas of my life, but my embroidery is the one place where I don’t feel compelled to do so. Whatever comes out, comes out. Sometimes it’s good, sometimes it’s only ok, and sometimes it’s pretty ugly. I just keep going.’

Choosing to work with discarded or unused and unloved textiles was also a positive choice for Lindsey, as is embroidering with fine, machine weight or button thread, handy for creating detailed repetitive patterns. For this artist, it’s the perfect combination of her aesthetic tastes and personal values.

But what most excites her is that this way of working always results in the unexpected. She never draws or makes a plan before starting a piece, and never unpicks her work.

The goal is to try to capture a feeling or an idea through her freestyle stitching.

Up close and personal

‘Basically, my work has been just an exercise in throwing my hands up, thinking to myself “whaddya gonna do?”, and then just keeping going.’

And her advice to others is similarly succinct. ‘Don’t worry so much. Just show up, get started. Make what you want to see more of in the world.’

Lindsey Gradolph (Lindzeanne) is a self-taught embroidery artist and English teacher based in Tokyo, Japan. Her work is inspired by traditional Japanese textile traditions such as Sashiko and Indigo dying, and also the concept of Mottainai or ‘waste nothing’.

Website: lindzeanne.com

Instagram: @lindzeanne

Line of enquiry

In this expressive series of thread portraits of local people, each character represents a personal impression of Taipei City developed from sketches and photographs. These were then scaled up and the all-absorbing ‘meditative’ process of plotting each image began, along with the winding and knotting of countless lines of thread.

‘I like the idea of using the most familiar textile materials (pins and thread) in an unorthodox way. Having worked with thread for some time now, I tend to see it as an alternate drawing medium. The process is very material-led; how the thread falls or knots often dictates my next step.’

Singled out, these materials appear flimsy and delicate, however when built, layer upon layer at a monumental scale, they become a robust tapestry-like architectural surface pattern: a quality that’s difficult to achieve through stitch alone.

Debbie discovered her technique while in her final year at university, intrigued by the idea of finding a way to lift the drawn line off the page. She says it’s important to experiment.

‘Get hands-on with materials and allow yourself to be material-led. It’s very easy to follow instructions with textile techniques, as it’s seen as a craft, but try not to. Deviate and see where you end up. Enjoy the process.’

UK artist Debbie Smyth established her studio practice in 2009 in Stroud, Gloucestershire. Her family-based design studio collaborates regularly with interior designers and architects, and counts companies such as Disney, Marvel, Ellesse, Adidas, BA, BBC, Mercedes Benz, The New York Times, and Sony among its clients. The three works from the FOLIO X FUBON series are permanently installed at Folio Da’an Hotel, Taipei.

Website: www.debbie-smyth.com

Instagram: @Debbiesmyth

Facebook: www.facebook.com/debbiesmythX/

Lisa Kokin

Materials can often act as a catalyst for new ideas, and Lisa Kokin’s practice thrives on this idea of chance and spontaneity.

Lisa is no stranger to the potential of found, often random, materials – from textiles, paper, books and metal to shredded money. She brings a textile sensibility to working with them within a conceptual framework. ‘My work is often a commentary on the world around me, incorporating the age-old Jewish response to adversity – humour,’ she says.

In Shooter, part of her ‘How the West Was Sewn’ series, Lisa reimagined the natural form of a branch, inspired by a set of discarded paperback books, which she rescued from her local recycling centre.

The techniques are straightforward – she machine stitched the outline of leaf veins directly onto the paperback covers, after backing them with bookbinding material and incorporating wire for rigidity. But she used the books’ ‘campy’ imagery to tell another story.

‘The machismo and violence were so overt, and over the top, that they begged to be rearranged and recontextualised.’

The medium is the message

The series was stitched in 2008, at the end of the Bush Administration, a time when Lisa hoped the cowboy mentality would soon ‘be left in the dust’. ‘How wrong I was! I continued to use the cowboy novels to comment on guns and the violence that is prevalent in our culture, and I make them now as commissions when asked.’

Trees and the natural environment were another influence since Lisa’s move to her current base in El Sobrante, a semi-rural area in California.

‘It adds a layer of richness because of the fragments of imagery and text, and also the unexpectedness of book parts being stitched into horticultural forms. I also like the symmetrical, conceptual element of tree to paper to book, and back to the image of tree and leaves.’

‘I love the fragments of imagery that occur, the inadvertent compositions that result from randomly cutting out the leaf shapes from the book covers. I make dozens of leaves and then start to arrange them by colour and shape until I have an arrangement that works. If I have to make more I do, until I’ve made enough to create a composition that works colour- and form-wise.

For Lisa, it’s an exciting approach that can bring huge rewards for anyone working with textiles creatively. ‘I would suggest that you regard materials that you encounter in everyday life as potential art supplies, not limiting yourself to what can traditionally be found in stores or online.’

Lisa Kokin’s work is in numerous public and private collections, including the Boise Art Museum, the Buchenwald Memorial, the di Rosa Preserve, Mills College, Kaiser Permanente San Francisco, Yale University Art Museum, and Tiffany & Co. She has received multiple awards and commissions in her four-decade long career. Lisa currently maintains a thriving teaching and mentoring practice.

Website: www.lisakokin.com

Instagram: @lisakokin

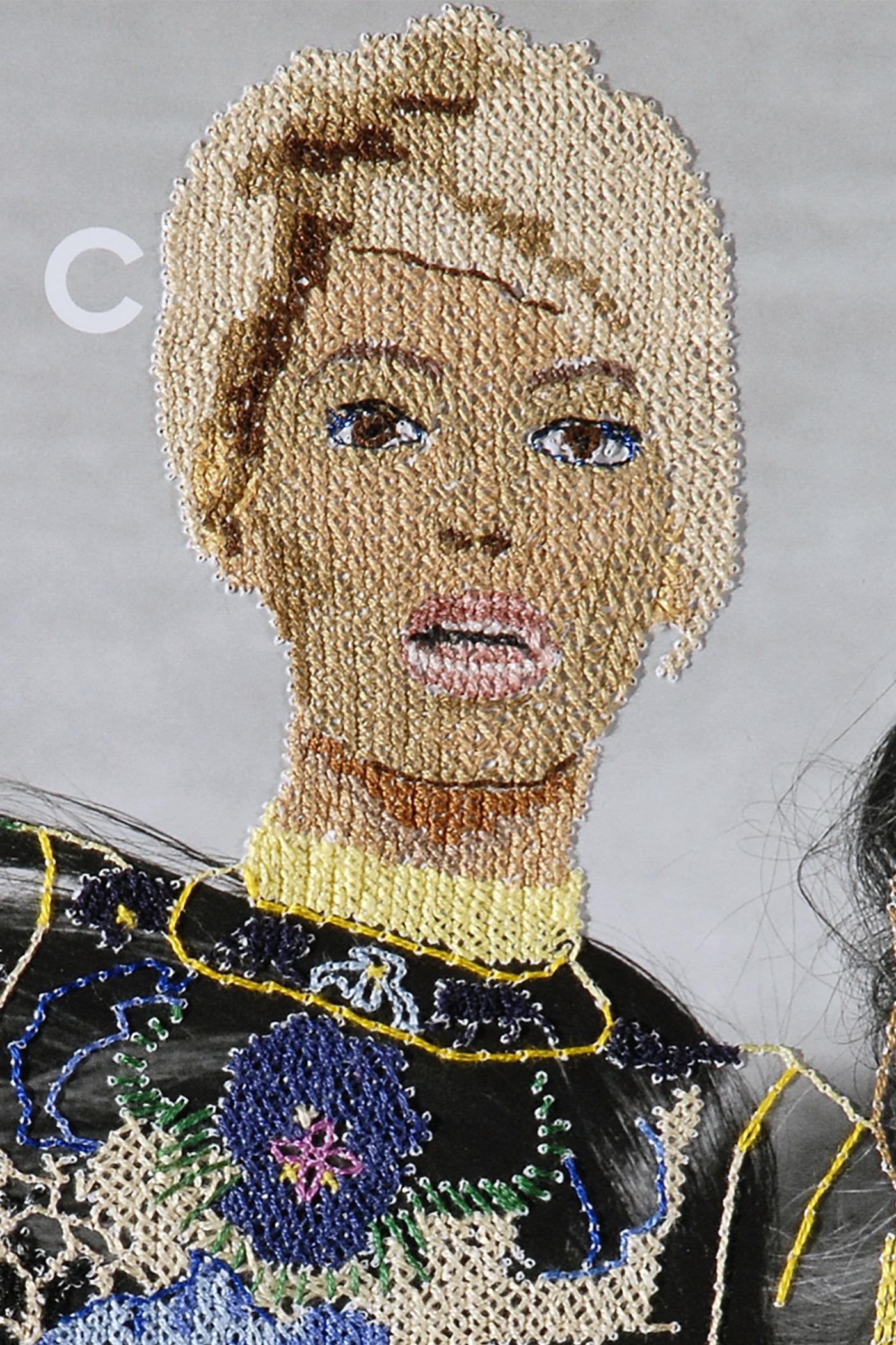

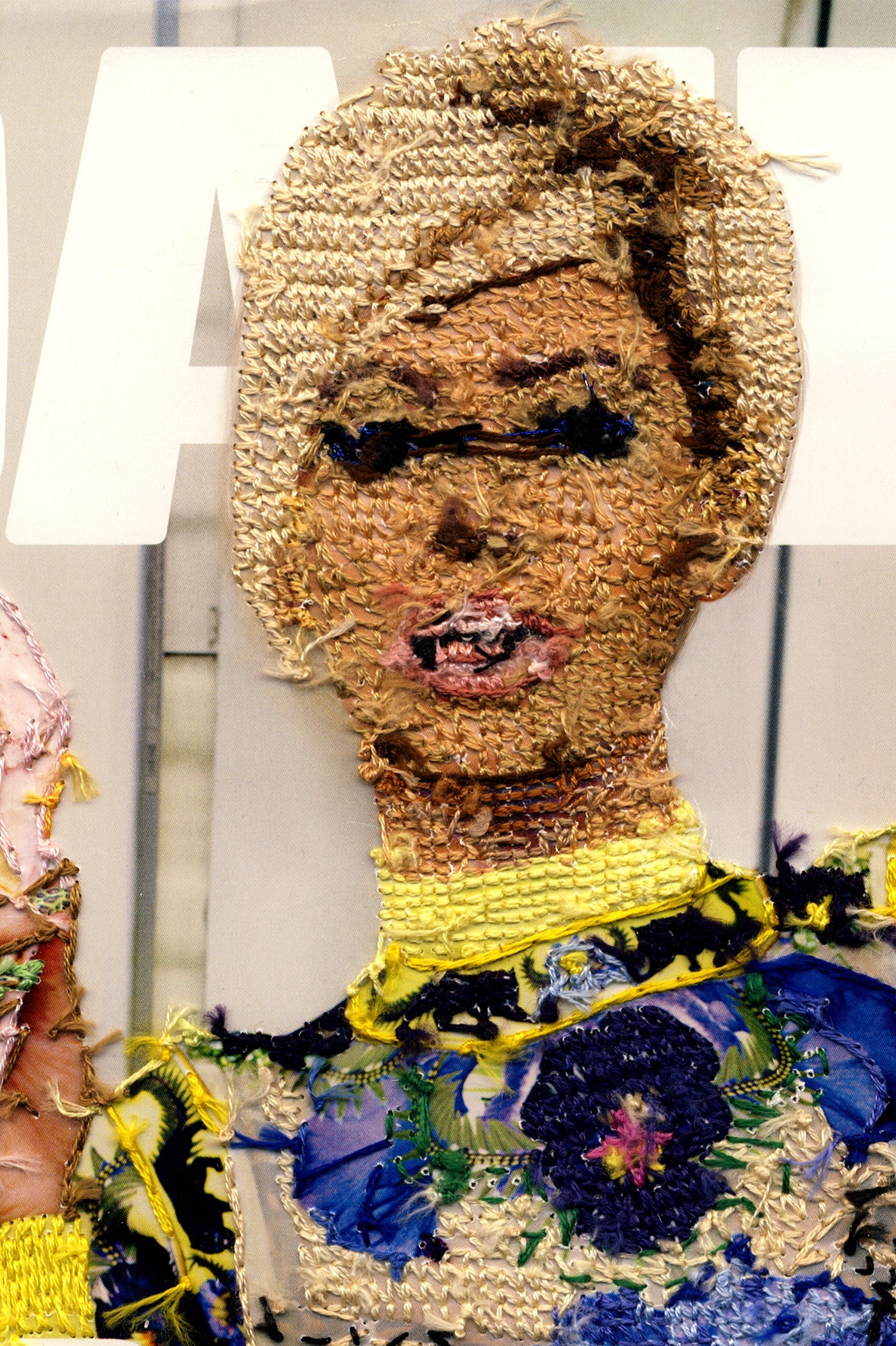

Inge Jacobsen

Centuries ago, the value of embroidery and lace lay not only in the time consuming and skilled nature of their production but in their exclusivity and signalling of status, as any portrait of Elizabeth I or Henry VIII reveals.

Today, mass-produced images infiltrate our every waking moment. They’re available for instant consumption, to be scrolled and liked, shared or forgotten, each quickly replaced by another in an instant.

So when Inge Jacobsen chooses to spend hours embroidering a magazine cover, an obsession that results in works such as Beyoncé – Dazed & Confused – Hijacked, the result is something of a conundrum.

Obscuring the cover star’s carefully selected outfit, her perfectly styled hair and make-up are thousands of meticulously hand embroidered cross-stitches, forming a pixelated yet recognisable facsimile of the singer.

And in a further twist, the cover is stitched from the back: ‘It was such a good image and outfit, I didn’t think embroidery would improve it, so I decided to disrupt it by inverting it,’ says Inge.

Beyond the surface

While the overall image is retained it is simplified. The embroidery is still an embellishment of sorts, yet it’s a playful subversion around the conventions of worth assigned to labour and materials.

‘Why would anyone in their right mind spend hours and hours carefully embroidering something that could melt if it gets wet or tear if you pull the thread too hard, right?’ It’s a question that Inge loves to consider.

‘I love working on magazines because for most people, once they’re read or looked at a few times they become disposable – more mass-produced artwork for the trash heap, so adding time consuming embroidery adds a certain uniqueness that’s lost in the mass-production process.’

‘It goes back to the idea of making something mass-produced unique, beautiful, delicate and special. I could embroider the same cover 50 times and each one would be unique.’

For Inge, the aim is to push beyond what’s expected. ‘You can do a lot with a needle and thread – physically and conceptually. I love appropriating images versus creating an image from scratch. There is nothing wrong with a bit of creative collaboration.’

Inge Jacobsen was born in Galway, Ireland where she currently resides. She attended Kingston University, London, graduating in 2011 with a BA in Fine Art Photography and has worked as a professional artist with brands such as Apple TV and WIRED magazine UK.

Website: www.ingejacobsen.com

Facebook: www.facebook.com/IngeJacobsenArtist

Instagram: @ingejacobsen

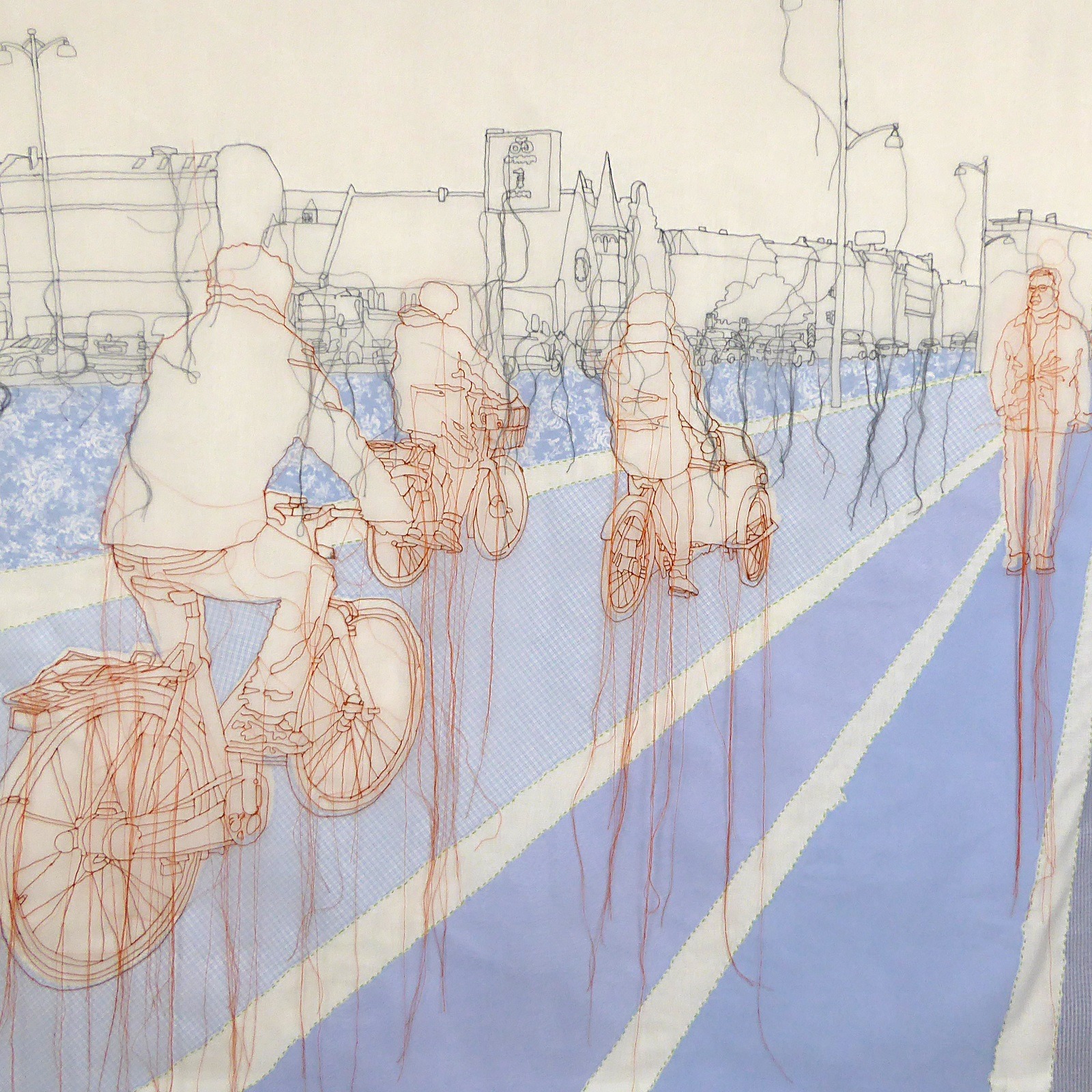

Rosie James

‘I love seeing how the stitched version of a photo will turn out,’ says Rosie James. ‘I think that the sewing machine has some say on what comes out the other end; you never quite know… But mostly I think I love the possibilities: there are so many different ways of working in this way and so many ideas to explore.’

Rosie James likes to use her sewing machine as a drawing tool, and photography as her inspiration. Her machine-stitched works are usually figurative, and composition is always a key element, something she’s intuitively drawn to.

Take Rosie’s artwork Copenhagen Streetlife, a textile hanging based on a photograph snapped in Copenhagen. Three cyclists pedal away from us, while a man strolls towards us – both elements are balanced on a long diagonal axis – a road that sweeps from the foreground into the distance.

Composed of two fabric layers, contrasting coloured stitched lines differentiate between the architecture (stitched in black on the base layer) and the figures (in orange on the top sheer layer). The ‘road’, made from blue shirting fabric is sandwiched between the layers, which are stitched together in green running stitch.

But there’s something else. The original photograph pictured the scene after a recent downpour; Rosie has used loose dangling threads to give the surface ‘a rainy feel’, as if the coloured threads are actually dripping from the surface.

It’s raining thread

‘I started out by having a go at free machine embroidery and realised the possibilities immediately as a form of drawing,’ says Rosie. ‘I think it achieves a different kind of line. It’s reliant on the machine, which creates a continual line. It’s a more flowing line and lends itself to the way I like to draw, which is a kind of contour drawing.’

Even though Rosie primarily works with two materials – thread and cloth – she’s adamant that the possibilities are endless.

‘Within those two things there are so many varieties… Thread can be anything from thick cord to very fine hair, it doesn’t have to be thread as such. What else could it be?’

And she regards her materials with the same curiosity. Any surface – ‘paper, card, plastic, whatever you have lying around’ is ripe for experimentation on her sewing machine. ‘Experiment,’ she says. ‘Also consider the loose threads: change the length, the colour of them, where they go, attach them, pull them straight. Consider all the possibilities.’

Rosie James is based near Rochester in Kent in the UK. She is the author of Stitch Draw: Design and technique for figurative stitching, and a member of Art Textiles: Made in Britain.

Website: www.rosiejames.com

Instagram: @rosiejamestextileartist

Lindzeanne

Eddies of white stitches swell into circular whirlpools, nudging up against thick, broad brushstrokes of thread and thousands of tiny stabs of cotton. Lindsey Gradolph’s stitch palette may be an economical mix of back, seed and blanket stitches, but she lets them meander over the entire surface of her cloth.

A kind of pattern emerges but it’s hard to pin down. There are hints of sashiko in the work, yet there’s none of the orderliness of the technique’s uniform lines of running stitch.

Lindsey (who goes by the online name Lindzeanne) lives and works in Japan. That’s where she developed her method of expressive hand stitching, which was actually born out of creative frustration.

‘I really was just desperate for an avenue to express myself… I’m always trying to create a visual landscape and record of my inner thoughts and ideas. I have never been adept at expressing myself with language. Abstract imagery combined with the thoughtful slowness of embroidery has been a lucky discovery for me.’

The idea of freely stitching in this way helped Lindsey to develop her own personal form of expressive, stitch vocabulary.

‘I’m an excellent over-thinker in all areas of my life, but my embroidery is the one place where I don’t feel compelled to do so. Whatever comes out, comes out. Sometimes it’s good, sometimes it’s only ok, and sometimes it’s pretty ugly. I just keep going.’

Choosing to work with discarded or unused and unloved textiles was also a positive choice for Lindsey, as is embroidering with fine, machine weight or button thread, handy for creating detailed repetitive patterns. For this artist, it’s the perfect combination of her aesthetic tastes and personal values.

But what most excites her is that this way of working always results in the unexpected. She never draws or makes a plan before starting a piece, and never unpicks her work.

The goal is to try to capture a feeling or an idea through her freestyle stitching.

Up close and personal

‘Basically, my work has been just an exercise in throwing my hands up, thinking to myself “whaddya gonna do?”, and then just keeping going.’

And her advice to others is similarly succinct. ‘Don’t worry so much. Just show up, get started. Make what you want to see more of in the world.’

Lindsey Gradolph (Lindzeanne) is a self-taught embroidery artist and English teacher based in Tokyo, Japan. Her work is inspired by traditional Japanese textile traditions such as Sashiko and Indigo dying, and also the concept of Mottainai or ‘waste nothing’.

Website: lindzeanne.com

Instagram: @lindzeanne

![Contemporary textile artist Lisa Soloman featured image||Lisa Soloman - Sen [1000 doilies]](https://www.textileartist.org/wp-content/uploads/Lisa.jpg)

Comments