San Francisco-based artist Bren Ahearn’s embroidery draws from a variety of cultural references. His work appropriates these recognisable symbols to question expectations about manhood and its assumed qualities of courage, vigour, and determination.

Bren’s samplers are imbued with feelings of tenderness, innocence, and tongue-in-cheek wit. He uses textile crafts to explore masculinity’s conflicting messages and employs the cross stitch ABC sampler form to document how he’s been educated to be a man in US society.

In this interview, Bren explains why cross stitch gives him room for self-expression like no other form. We learn about his creative family, where his interest in gender comes from and how exploring his own history continues to influence his style and life beyond art.

The thread of the conversation

TextileArtist.org: What initially attracted you to textiles as a medium?

Bren Ahearn: I got into textiles by accident. In 1996 I went to the local craft center to sign up for pottery, but pottery was full. So, I signed up for weaving instead. At first, I thought that my choice was random; however, I can see the textile influences in my life. My grandmother crocheted afghans, my mother is a quilter, my sister is a skillful sewer who has created costumes for theatrical productions and has worked on a few designers’ collections for the most recent New York fashion week, and my brother is a puppeteer who makes the costumes for his puppets and himself. Though my other two siblings do not work in textiles, they work in other creative media — my brother is a woodworker/singer, and my sister is a graphic designer.

What or who were your early influences and how has your upbringing influenced your work?

My mother encouraged all of her children to pursue creative activities. So, I did all sorts of crafts activities during the crafts renaissance in the USA during the 1970s. I tried decoupage, sand art, candle-making, rock-painting, shrinky dinks, string art, etc. Though my mother encouraged us to be creative, I’m afraid that there were external forces from society that discouraged certain types of creativity for boys. As a result, I went into the crafting closet and eventually stopped most crafting activities.

My mother also encouraged us to play musical students. Though I do not play the French horn and piano anymore, I’m grateful for the training and for having my eyes opened up to a new world and language. I still do sing every day.

Additionally, my mother was an English language arts teacher, and I remember spending many hours playing scrabble with her. She instilled in me a love of language and the power of language. After I had started working with textiles, I learned that the words “text” and “textile” come from the same root, meaning “to weave,” and this text-textile connection is evident in English, e.g., “spin me a tale,” “the thread of the conversation,” etc.

And, more specifically, how was your imagination captured by stitching?

In 2007, I decide to go back to school for art. I decided to switch to embroidery because I have always been interested in gender, and I thought I could exploit embroidery since in recent times embroidery has been gendered feminine in the US and Europe. I learned to cross stitch from Connie Barwick on the website about.com. I am grateful to Connie for posting these instructions, and I call her Connie-sensei.

My earliest embroidery pieces were my manmades, for which I stitched the word “manmade” onto found objects with a woven pattern. In particular, I was interested in working with molded plastic objects. I am fascinated by the lifting of textile motifs and the rendering of them in non-textile media. Why does a molded plastic basket have to look like a woven basket? What as a society do we get from recreating these motifs?

In the November/December 2005 issue of Fiberarts magazine, Debra Valoma addresses in detail this migration of textile motifs to other media, such as architecture, pottery and brickwork.

We are born a blank slate

What was your route to becoming an artist?

While the manmades addressed topics such as machine–made versus human-made, sexism in language, etc., they really did not tell my story. This is where my mentor and advisor, Vic De La Rosa, comes into the picture. His artwork deals with topics such as his ancestry, his history and population migrations, and I am so grateful to him that he encouraged me to explore my own history when I started school.

At the same time, Northern California artist Barbara Shapiro saw that I was interested in embroidery, and she gave me this wonderful opportunity to view a prominent embroidery sampler collection. Thanks to her and Mrs. Marian Soss, the owner of the collection.

During the collection viewing and subsequent research, I learned that samplers were typically done by European and Euramerican girls for a variety of reasons at different periods in time. For example, for some girls, this was the only education they got – they learned the ABCs by stitching them onto cloth. For others, this sampler was used later in life as an actual example of monograms the women would stitch onto their textiles. For others, embroidery was a mark that one lived a life of leisure and did not have to work in the fields.

In the book [easyazon_link identifier=”1848852835″ locale=”UK” tag=”wwwtextileart-21″]The Subversive Stitch by Roszika Parker, Parker notes that the gendering of embroidery as feminine is a relatively recent phenomenon. She notes that during the medieval era, both men and women embroidered, and that during the Victorian era, embroidery was deemed essentially feminine.

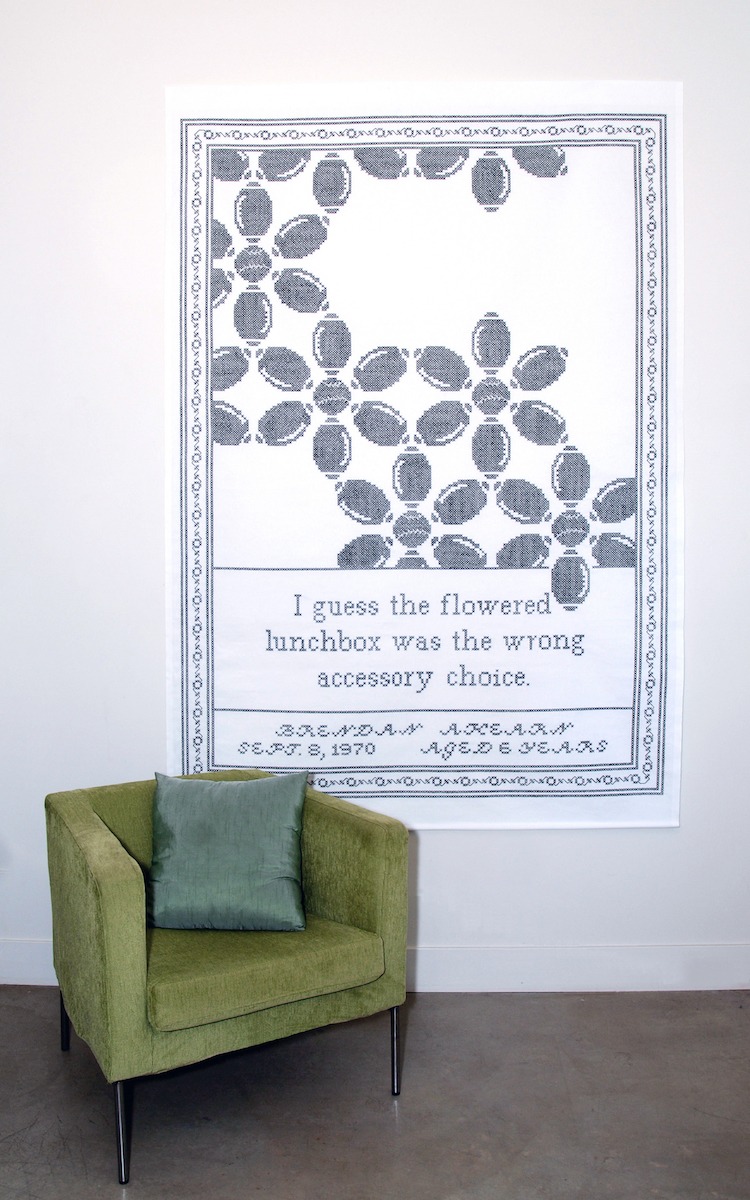

During the viewing of the collection, I noticed that a number of the samplers show the ABCs, the name of the person who stitched the piece, the date of completion, and some sort of religious or moral saying about how to be a proper woman. This got me thinking about how I have been educated to be a man in American society, and the samplers were born. The first thing that came to mind was the socialization of American men to be violent, whether it be physically violent, verbally violent, or violent by taking up more than one’s fair share of space. I also thought about Judith Butler’s notion of gender as performance, that is, we are born a blank slate, and society tells us how to act by giving rewards for “appropriate” behavior and punishments for “wrong” behavior.

Symbolic cross stitch

Tell us a bit about your chosen techniques.

I decided to use cross stitch because it looks old-fashioned and because it was a technique used by the girls way back when. At the time, I did not realize the cross stitch could be symbolic of other things. For example, the stitch is an X, which can symbolize the erasure of “women’s work” from history. Also, an X can be a signature, perhaps the signature of anonymous stitchers. Moreover, an X is composed of two slashes, perhaps symbolizing a binary, opposed structure, e.g., male-female, us-them, and in the US, Democrat-Republican. I had none of this other symbolism in mind when I first started working in cross stitch. That’s the nice thing about art – sometimes other things pop up.

I also use running stitch, double running stitch and French knots. Rarely have I used chain stitch or fly stitch. I have a pretty limited stitch repertoire.

I have done some pattern repeat design and have had the patterns printed. I would like to revisit pattern repeat. I created this design while I was in Vic De La Rosa’s pattern repeat course at San Francisco State University.

Notions of femininity

How do you use these techniques in conjunction with cross stitch?

I typically use cross stitch for the main design, running stitch for lines, double running stitch for skinny lettering, and French knots for dotting I’s.

How would you describe your work and where do you think it fits within the sphere of contemporary art?

The curator of my show at the Bellevue Arts Museum, Stefano Catalani, is much more eloquent than I could ever hope to be and wrote this about my work:

“In the artist’s hands, needlework—with its history of exclusion from the (capital A) Art world as result of its association with notions of femininity, the triviality of everyday domesticity, and hobby-ish woman’s leisure—becomes a narrative device to address the culturally-shunned topic of a man’s sensitivity.”

More info about that show is below.

Do you use a sketchbook? If not, what preparatory work do you do?

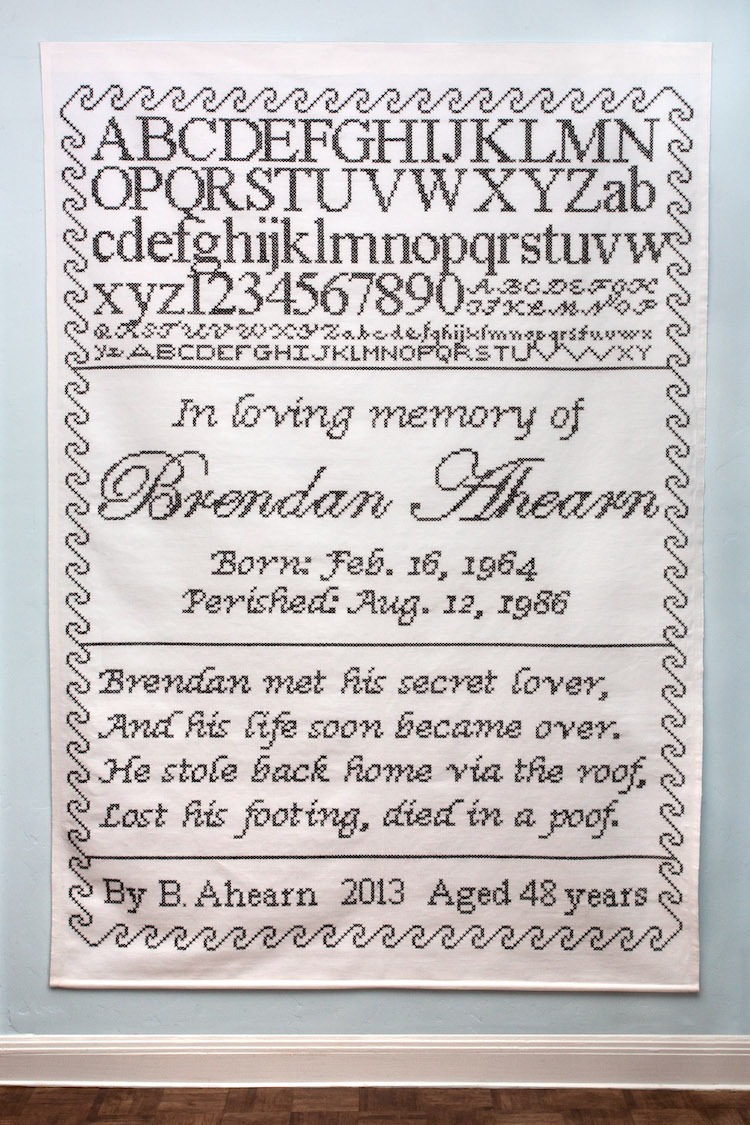

I use an idea book, rather than his sketchbook, because I don’t know how to draw. In this book I write down ideas, as well as work out the text on my samplers. I am looking at my book, and I see that this sampler had at least 3 earlier iterations for the text before I decided upon the final text:

Tell us about your process from conception to conclusion.

Typically, something strikes my fancy, and I write a quick little note in my book. For example, for my death samplers, I see a page in the book called “headstone project”.

Let me take a step back to explain the death samplers. I often read the news online, and I am saddened that people leave horrible comments at the end of tragic stories. Some example comments might be, “Darwin award” or “that person should have known better.” It makes me sad that people do not have compassion. I started to think about times in my life when I exhibited risky behavior, but I just was lucky and am alive today. I decided to document a parallel history in which I was not so lucky and died, and I decided to stitch headstones to document those times.

I see in my notebook that I then brainstormed a bunch of potential headstones inscriptions about situations from my past, e.g., “he should have used a condom” and “he should have not driven after that last drink.” On the next page, I see a note that says “Don’t do headstones. Rather, do large samplers.” This makes sense with my body of work and also historically, since there was a tradition of mourning samplers, and a number of old samplers deal with mortality.

For the sampler below, I revisited the ABC format and decided to revisit a real-life situation when I climbed over the roof to have a tryst with my secret lover. In this parallel history, however, I fell to my death. I have other death samplers in which I’m found dismembered in a park, run over by a trolley, pricked by an infected needle, etc.

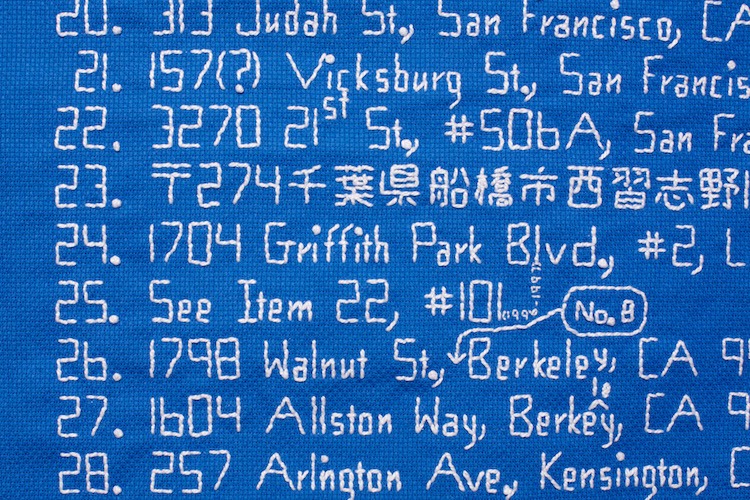

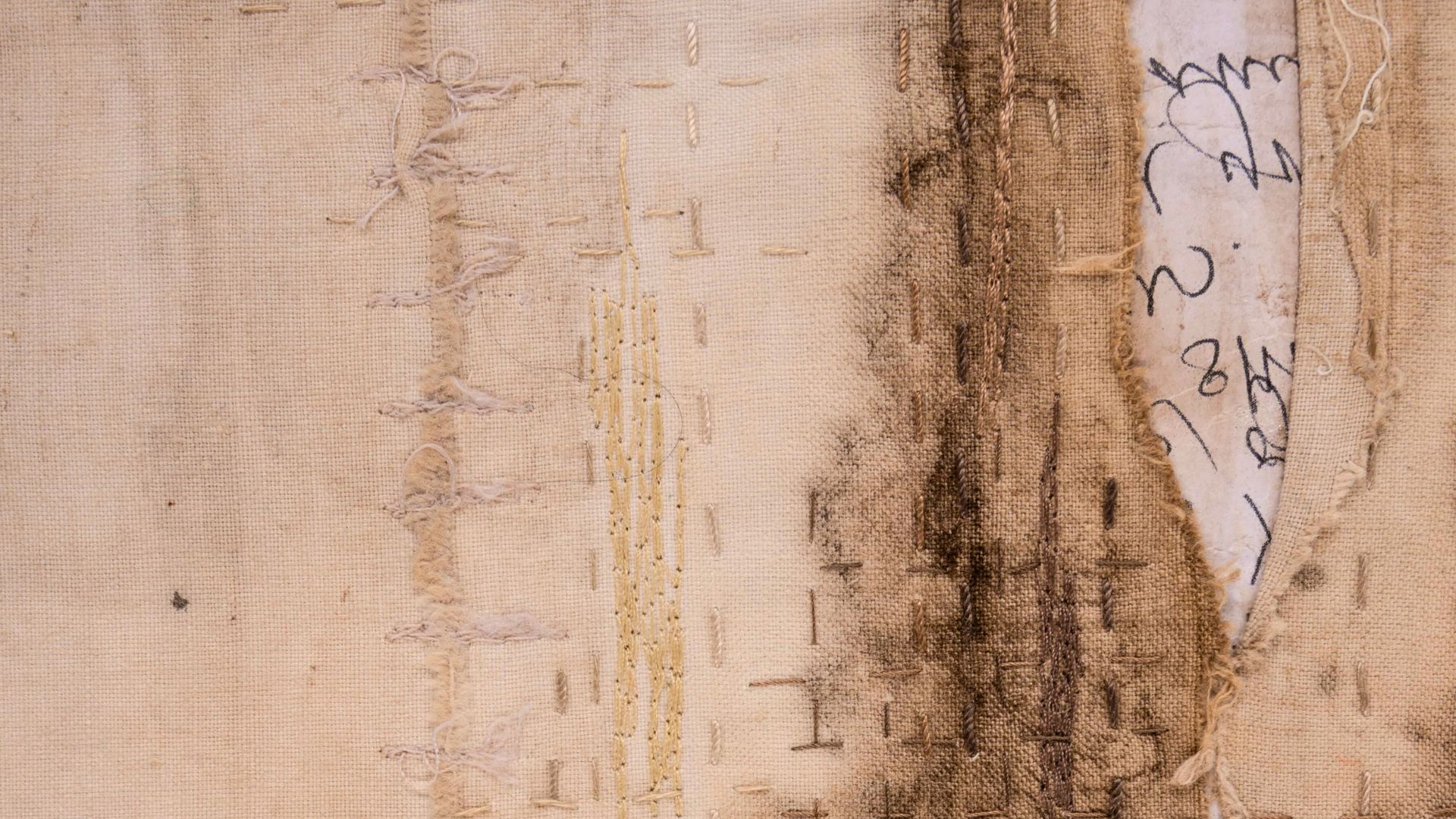

Getting back to the process– once I decide upon what I’m going to do, I draft out the sampler in Stitches for Mac, a cross stitch program. Though the design is pretty much set before I start, there still is room for some freedom and errors, as you can see from the below blue sampler documenting my various addresses. These errors are more in line with how real old-fashioned samplers were made.

If you’re interested in the nitty-gritty details, for the large samplers, I use 14-count AIDA cloth, 60″ wide. For readers who are not familiar with this cloth, AIDA cloth is woven with little evenly-spaced gaps, which the stitcher uses as a guide. So, 14–count cloth has 14 gaps/inch in each direction; both vertical warp and horizontal weft directions. I like using this cloth because it is used by home crafters and doesn’t have the same prestigious status as linen or other fancy fabric. I view my work as firmly rooted in the home craft realm, since I grew up in this tradition.

The yarn I use for these bigger pieces typically is 3/2 cotton from UKI. For cross stitch, each half of each cross goes over three blank holes and down into the fourth hole.

For the smaller samplers, I use the same cloth and embroidery floss from DMC or Presencia. The floss goes up one hole and down the adjacent hole. I do have two samplers with a linen base cloth.

For a few medium-sized pieces I use 5/2 cotton over one blank hole and down the second hole.

A form of instruction

What environment do you like to work in?

I like to meet with others to discuss work and get inspired from them, and then I prefer to work at home with only me or my husband and me at home, since I tend to be more of an introvert. Working in a studio with lots of people around is too chaotic for me. I like it to be quiet when I am designing, but sometimes I listen to the radio when I am stitching. I think my listening to the radio distracts me, which leads to errors, which I like.

What currently inspires you?

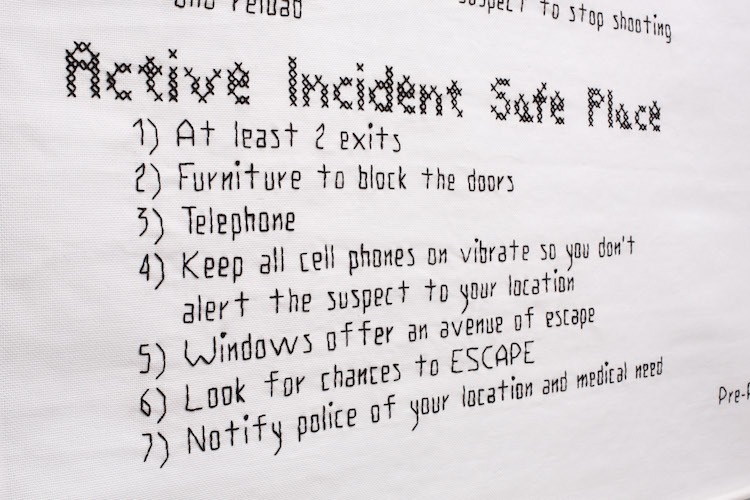

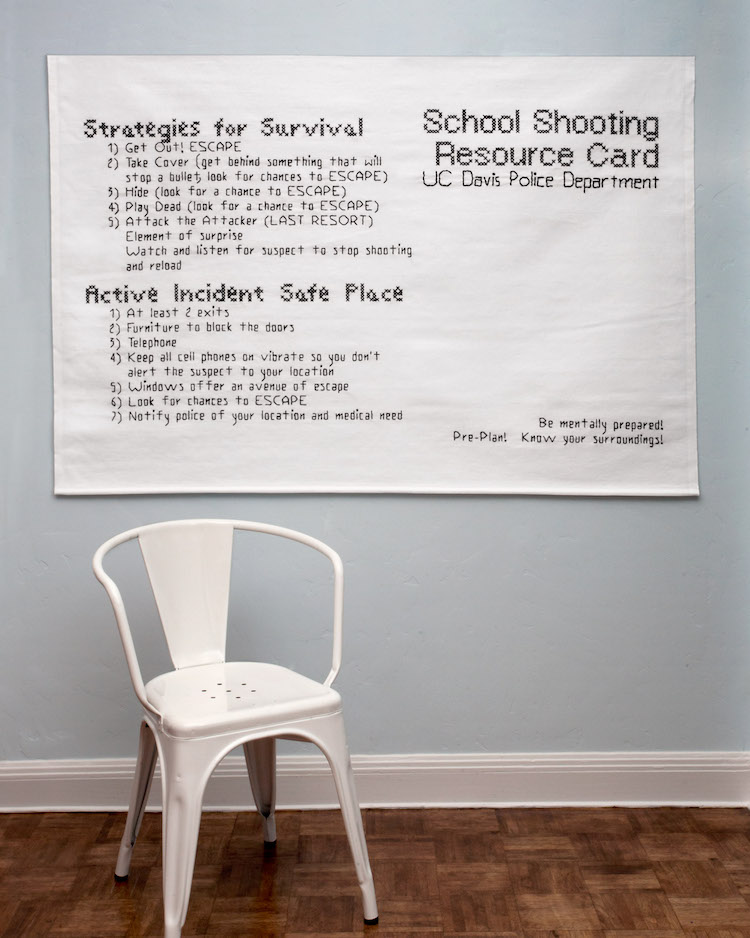

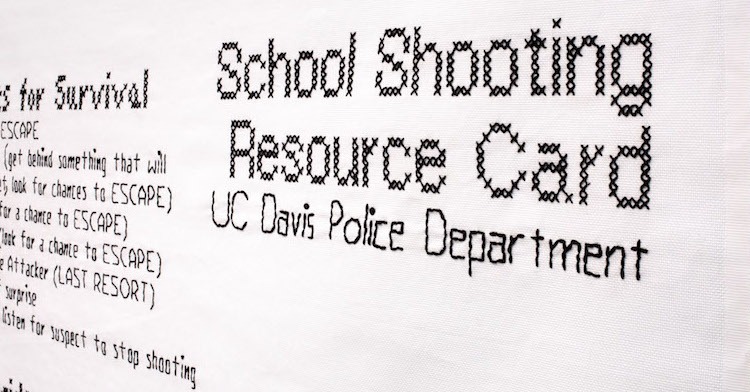

Since 2011 I have been inspired by active shooter situations. When I worked at UC Davis, they called all of the first year medical students and staff into the auditorium for a program about what to do if someone comes in and tries to kill everyone. At the end of the assembly, they gave us all a handy card with directions. I thought that it was crazy that they were not addressing the underlying things in American society that cause people to kill each other. So, I decided to stitch a large version of this card.

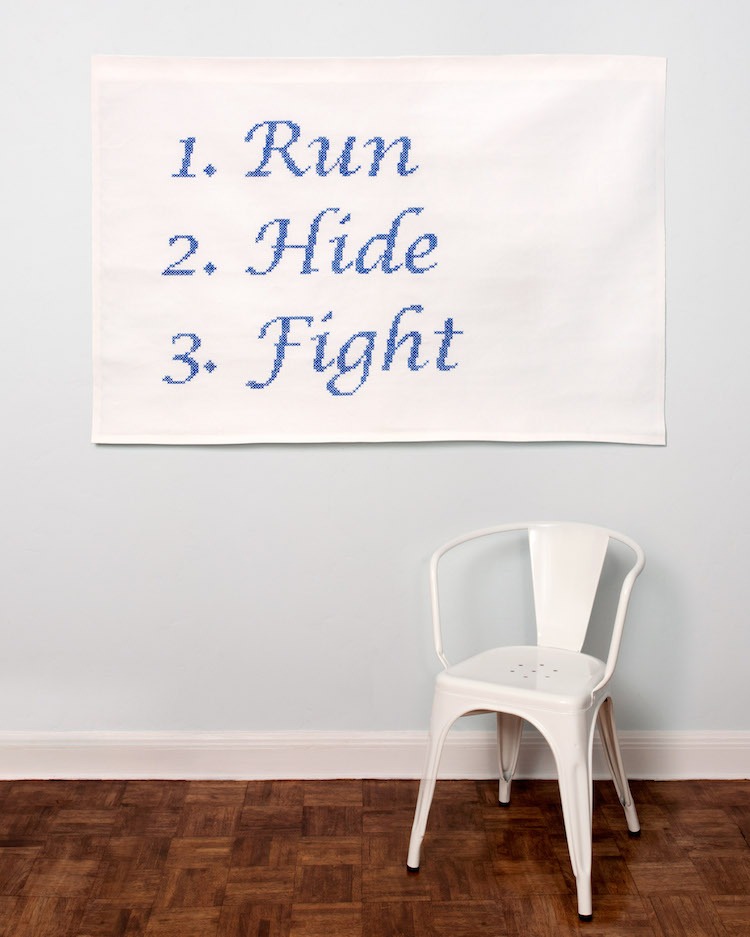

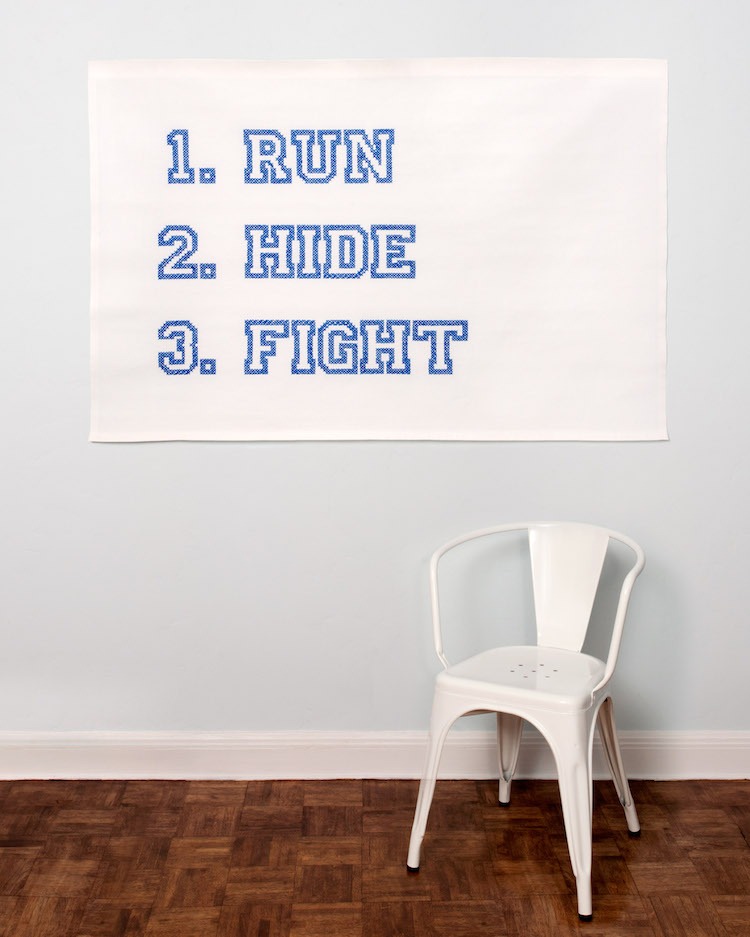

More recently, I have started a new series of pieces based on stripped-down active shooter directions from the US Department of Homeland Security. I have stitched the words “run,” “hide,” “fight” on each piece. Each piece is in a different font, and I view this series as my next generation of samplers. Given the fact that the active shooter directions are a form of instruction, this fits in with the idea of samplers as education.

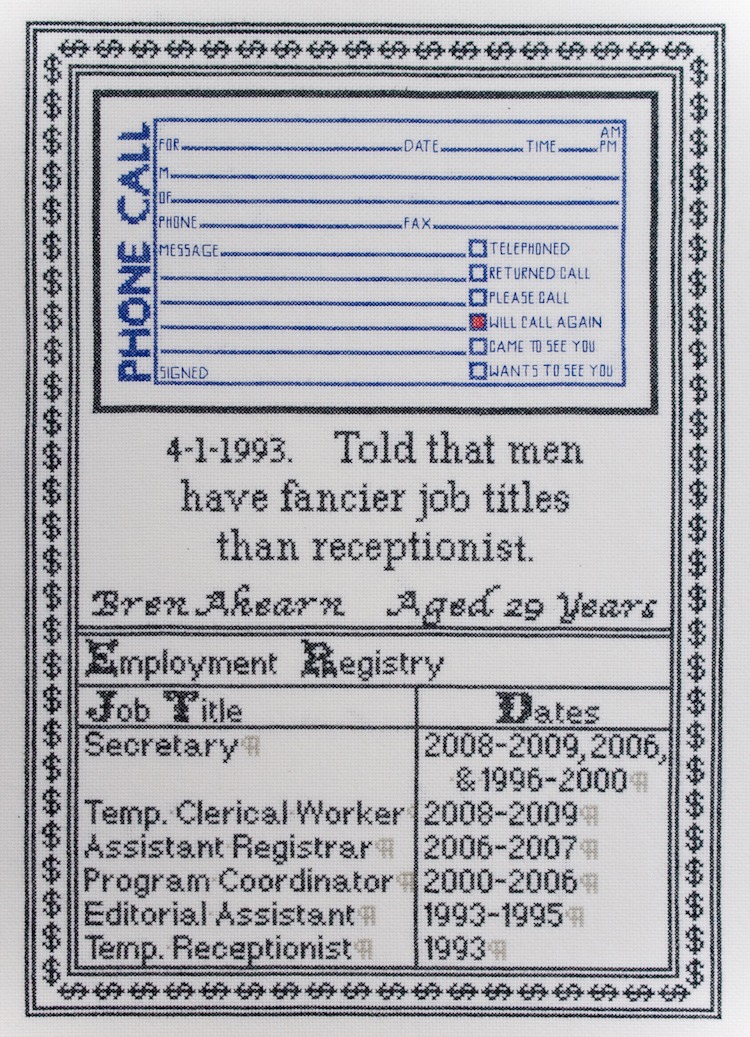

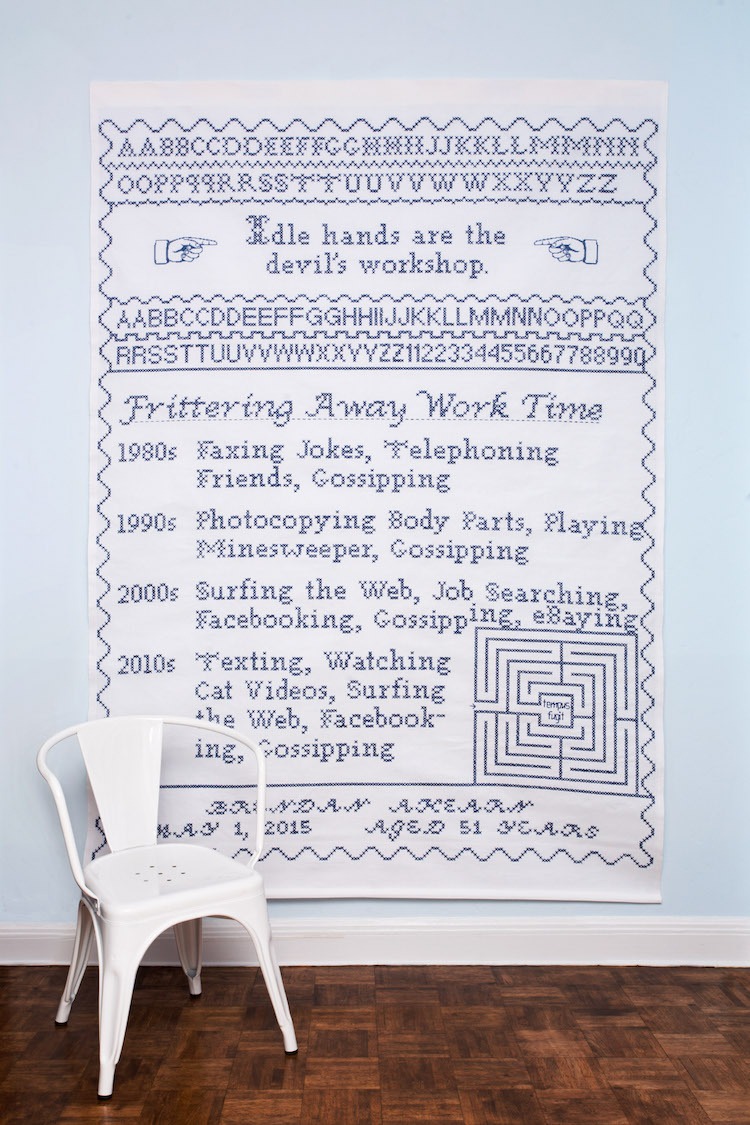

Additionally, I have been revisiting my work history. In one sampler, I document how I have wasted time at work through the decades, and in another, I document employment that does not appear on my resume.

If you go to my website, you will see that I had begun to incorporate labyrinths in my more recent samplers. One of my professors, Jim Davis, turned me on to labyrinths and taught me a bit about the history/symbolism of labyrinths. For example, in some situations, worshippers at the local cathedral would walk the labyrinth, and it was hoped this activity might lead to some sort of aha moment or awakening or awareness when one reached the center. I’ve realized that sometimes the awareness in life isn’t grand, though; sometimes it’s a little thing, like realizing that time is fleeting, as is referenced by the “tempus fugit” in the center of the labyrinth in the above piece.

I also have created a piece with a multicursal (many-pathed) labyrinth. Here’s an aside about multicursal labryinths: in the legend of Theseus and the Minotaur, as Theseus is going into the labyrinth to slay the Minotaur at the center, Ariadne gives him a ball of yarn for him to unroll and leave on the ground as he walks so he can find his way back out. This ball of yarn was called a “clew,” and the work “clue” in English is related to this word.

My story and the bigger picture

Who have been your major influences and why?

As noted above, my mother has been an influence from an early age.

My husband, Doug Brown, has also been a major influence. He’s a landscape architect who has inspired me to be creative in all my endeavors. He has given me honest critiques, and he has given me so much support over the years.

Along those lines, my friend Frankie Hernandez has taught me how to live a creative life and to create the life I want to live.

My grad school advisor, Vic De La Rosa, got me to go inward and look at my story.

My grad school queer art history professor, Richard Mann, inspired me to look at how my story and artwork fits into the bigger picture of LGBTQ history and LGBTQ art history.

My grad school art history professor, Santhi Kavuri Bauer, introduced me to the concept of the microhistory, which is the history of the common person, rather than history with a capital H.

My grad school professor, Jim Davis, turned me on to labyrinths and my new direction.

My grad school professor, Gail Dawson, taught me to believe in myself.

My professor, Ana Lisa Hedstom, got me to loosen up!

Thanks to all of these folks and the others along the way.

Tell us about a piece of your work that holds particularly fond memories and why?

My favorite piece is my Active Shooter Directions #1 because it is so relevant (unfortunately) and taboo at the same time. I currently have a show called Bren Ahearn: Strategies for Survival, at the Bellevue Arts Museum (Bellevue, WA, USA). When the curator, Stefano Catalani, came to my place for a studio visit last year in preparation for the show, I had this piece prominently displayed because I really wanted it in the show. When he saw the piece, he saw the words “Strategies for Survival,” and he said that would be the title of my show. I’m grateful to Stefano and the folks at the Bellevue Arts Museum. They put in a lot of work to make the show happen.

How has your work developed since you began and how do you see it evolving in the future?

I started with the simple manmades. I then moved to the samplers, which I feel invite more complex introspection and dialogue. Recently, I have moved to the stripped-down active shooter directions, so perhaps I am regressing. I was going to do some 3-D work, but that is on hold right now. In the future, I possibly see samplers without words.

What advice would you give to an aspiring textile artist?

Be yourself and tell your own story. Be vulnerable and put yourself out there. Don’t be so serious. Throw in some death and destruction for good measure.

Can you recommend 3 or 4 books for textile artists?

This book is relevant to my art practice: [easyazon_link identifier=”1848852835″ locale=”UK” tag=”wwwtextileart-21″]The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine by Roszika Parker

I love thumbing through this resist-dyeing book and have used it a lot: [easyazon_link identifier=”B00FGY4WNQ” locale=”UK” tag=”wwwtextileart-21″]Shibori: The Inventive Art of Japanese Shaped Resist Dyeing by Yoshiko Iwamoto Wada, Mary Kellogg Rice and Jane Barton

This is about living in a society that glorifies extrovertism: [easyazon_link identifier=”0241273552″ locale=”UK” tag=”wwwtextileart-21″]Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking by Susan Cain

What other resources do you use? Blogs, websites, magazines etc.

The world around me, in particular violence, is my inspiration.

I don’t look at too many artists’ websites because I am afraid that I will be influenced by and unconsciously copy their work.

I like looking at home magazines. I have always had an interest in architecture that I have never pursued.

I like looking at the self–help section of Oprah Winfrey’s O magazine; however, I feel as though there are mixed messages in the magazine. On the one hand, women are given tools to empower themselves. In other parts of the magazine, there’s a focus on beauty products, fashion and consumerism, perpetuating the idea that a woman is an object whose life will be better if she only makes herself more beautiful and buys objects.

Making whatever I want

What piece of equipment or tool could you not live without?

A needle.

Do you give talks or run workshops or classes? If so where can readers find information about these?

For my current exhibit at the Bellevue Arts Museum, I just gave a gallery walkthrough and talk. I will return in the fall for a more formal lecture with slides, during which I will discuss my various bodies of work. The date is TBA.

Last year I was on a panel at the Mid-Atlantic LGBTQA Conference at Bloomsburg University in Pennsylvania (USA), in conjunction with an exhibit there. If my work is accepted into this year’s show, perhaps I will appear again on the associated panel in November if I am invited to do so. That’s a whole bunch of “ifs.”

How do you go about choosing where to show your work?

I typically show my work in not-for-profit settings, museums and educational institutions because these venues nave built-in education departments that typically sponsor public programs/panels in conjunction with the exhibits. It is my hope that my work inspires dialogue and encourages people to question their assumptions. Also, it is nice working with institutions in which I do not have to worry about selling my work, i.e., I can make whatever I want. Whether the venue chooses to display the work is another story.

Where can readers see your work this year?

Until January 15, 2017: Bren Ahearn: Strategies for Survival at the Bellevue Arts Museum

Also, I will have a few pieces in the Social Fabric/Moral Fiber exhibit at Gallery West, Grant Campus of Suffolk County Community College, Brentwood, NY, USA, February 14-March 30, 2017. The curators are Leila Daw and Michaelann Tostanoski, and I will post info on my website.

A few times year my photographer takes photos of my new work, and I post these images, as well as info on other shows on my site.

Thanks for this opportunity to chat about my work

For more information visit: www.brenahearn.com

Let your friends know about this artist’s work by sharing the article on social media. It’s easy – click on the buttons below!

3 comments

Amanda Watson-Will

This is a great interview. A wonderful mix of both conceptual discussion and practical info. Much appreciated!

Ansie van der Walt

This is an excellent interview. Both the artist and the interviewer did a great job.

I love Bren’s work and the way he talks about it (text & textile) – Bren, you know how to spin a tale!

Congrats to both of you.

K Wayne Thornley

Bravo.