A full-time artist since 1994, Yvette Kaiser Smith has exhibited extensively at regional museums, art centres, and university galleries throughout the United States of America.

She has also exhibited in U.S. Embassies abroad including Moscow, Ankara, and Abuja and in alternative galleries in London, Rome and Berlin. In 2005, Yvette began working with art consulting firms, galleries, and individual clients to create site-specific, private and public commissions.

In this interview, we learn about Yvette’s signature process of crocheting fiberglass and generating work using math as a starting point, and how a significant journey back home to Prague had an enormous impact on her art.

The language of crocheted fiberglass

TextileArtist.org: What initially attracted you to textiles as a medium?

Yvette Kaiser Smith: The road towards my signature process of creating math generated work and crocheting fiberglass really began in 1992 when I started making sculpture that dealt with abstracting narratives of identity. Within this context, an exploration of fiberglass and resin led me to crocheting fiberglass roving.

In summer 1994, I first began exploring traditional fiberglass forms and techniques and trying to understand the language of fiberglass and how to use it to articulate my conceptual agenda. During this time, I found the roving. Having used iron wire in school for forcing a shape by binding, I bought a spool and began to play. All a total failure. I shoved the roving in the corner and forgot about it.

Around November 1996, I was starting to work on my first 2-person show, my narrative was still limited to the body and dichotomies were a large part of the dialogue. I was at an all-night grocery at one o’clock in the morning, running by the meat counter, from the corner of my eye, I saw tripe!! I stood there frozen in time as thoughts rushed through my head. I saw fat, I saw lace; beauty and ugliness; lots of personal identity stuff came flooding in. Without recognizing why I associated lace with crochet.

The next day I found a hobby store, purchased a book that teaches you how to make potholders and baby booties, every size of hook available, and began to crochet. It took another 3 years or so before I began to understand the material language of crocheted fiberglass vs. the language of prefabricated fiberglass matt and cloth.

And, more specifically, how was your imagination captured by crochet?

Just about every culture, current and extinct, has and had its own lace or knotted cloth tradition. The tradition of crochet, the process of crocheting, and the construction of identity all touch some aspect of human history, traditions, groups, constructs, patterns, and memory; they embody passing of time, human labor, and innovation and creativity.

The narrative based crocheted fiberglass (all works from 1996 to 2006) as well as the math-driven crocheted fiberglass (all works from 2007 to present) reference culture and humanness; they represent time and community; the work highlights our connectivity. If identity is a hybrid of our heritage, then lace is, as tradition of time, labor, and creativity, one tiny point of intersection that connects us all.

Creating simple geometric shapes

How do you use these techniques in conjunction with crocheted fiberglass?

Fiberglass as a finished product is a fiber reinforced plastic. Fiberglass as raw material is a fiber made from spun glass. It is white, opaque, pliable, and behaves as a heavy cloth. It is commonly combined with polyester resin, a liquid plastic. Normally, the resin wetted cloth is laid into or over a mold until the material cures into a hard, translucent surface.

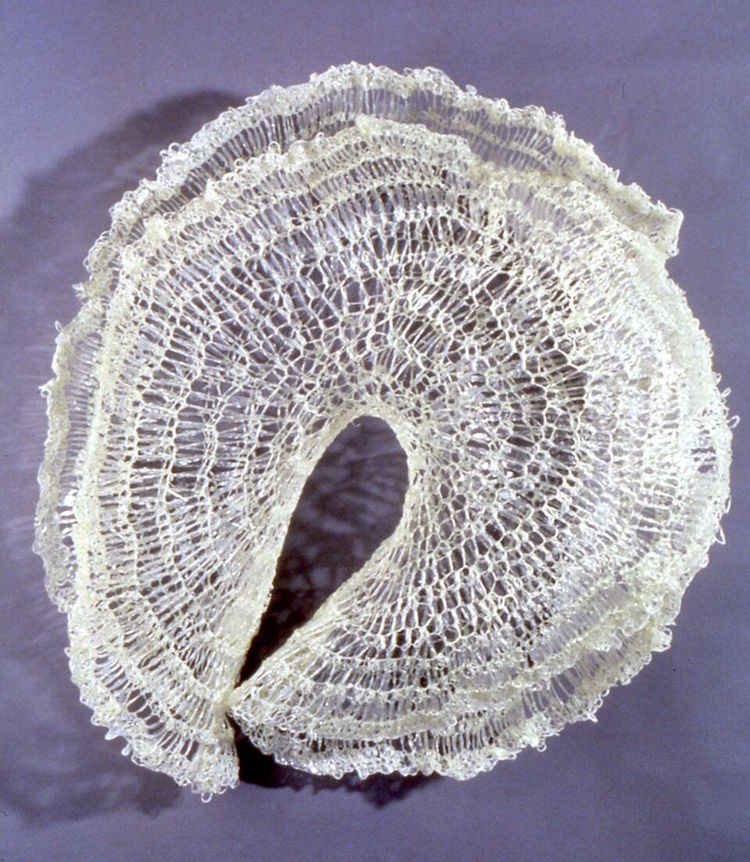

I start with a form of fiberglass called continuous roving or gun roving. Gun roving comes as a large spool of clustered continuous strands of fiberglass. I crochet the roving with a regular crochet hook to create my own cloth. The “J” hook is just big enough to pick up the thickness of the roving. Using a variety of traditional stitches, I crochet flat geometric shapes: circles, rectangles, squares.

For the next step, I use a hard finish polyester resin. This is polyester resin with 5% styrene wax. As the resin cures, the wax comes to the surface and forms a hard finish which is sandable and eliminates the perpetual surface tack and smell of regular laminating resin.

I do not lay my wet fiberglass into a mold, which is standard practice when working with fiberglass because the crocheted cloth loses its dimensionality and becomes flat and ugly. Instead, I use gravity to create simple geometric shapes by hanging and draping.

How would you describe your work and where do you think it fits within the sphere of contemporary art?

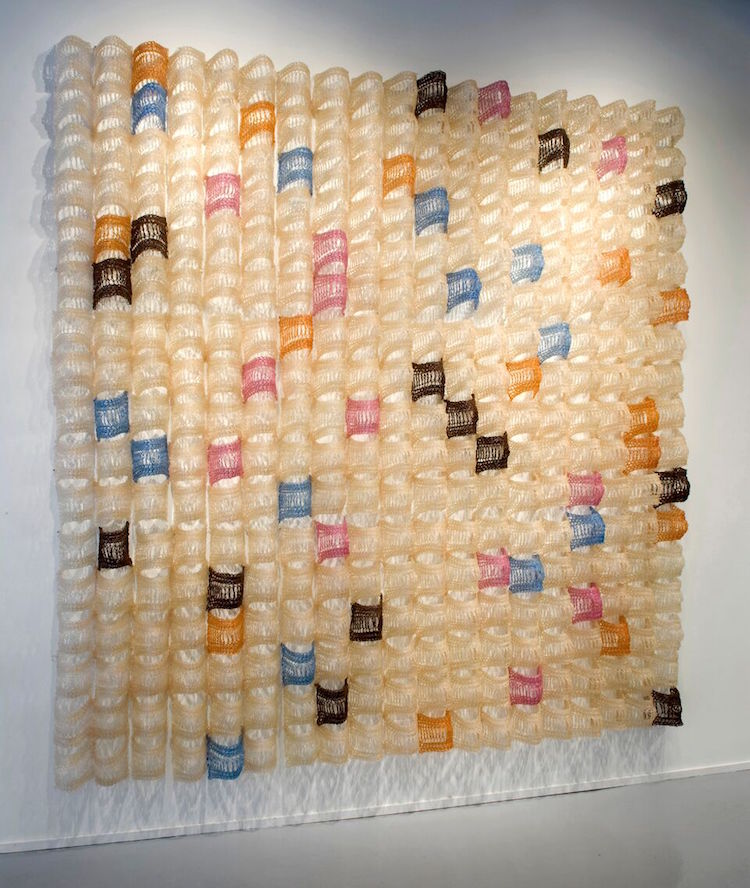

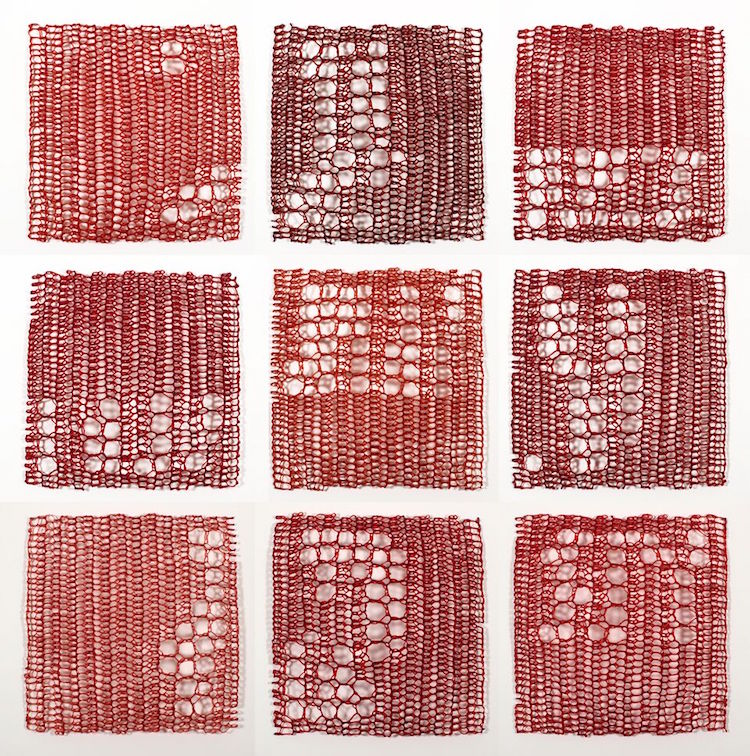

Sequences from transcendental numbers pi and e, prime numbers, grids, and simple geometric shapes are my obsession. I devise systems for visualizing numerical values by which I can create new and uncommon patterns where the grid serves as an armature for plotting sequences, and grid and sequences serve as armatures for exploring patterns.

The majority of my past works are wall-based, geometric, crocheted fiberglass constructions in which Pascal’s Triangle and/or value of digits from specific sequences define spatial relationships and colour distribution.

These hybrids combines the past, the present, and multiple disciplines. They are products of time-based manual labor that have been contemporized by the use of the industrial materials of fiberglass and polyester resin, mathematics, and the language of art and architecture.

Dare I say my work loiters in the shadows of sculptural, experimental, abstract fiber artist icons like Eva Hesse, Magdalena Abakanowicz, and Elsi Giaugue.

Do you use a sketchbook? If not, what preparatory work do you do?

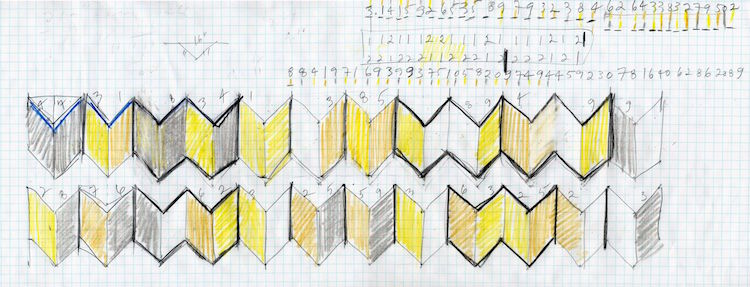

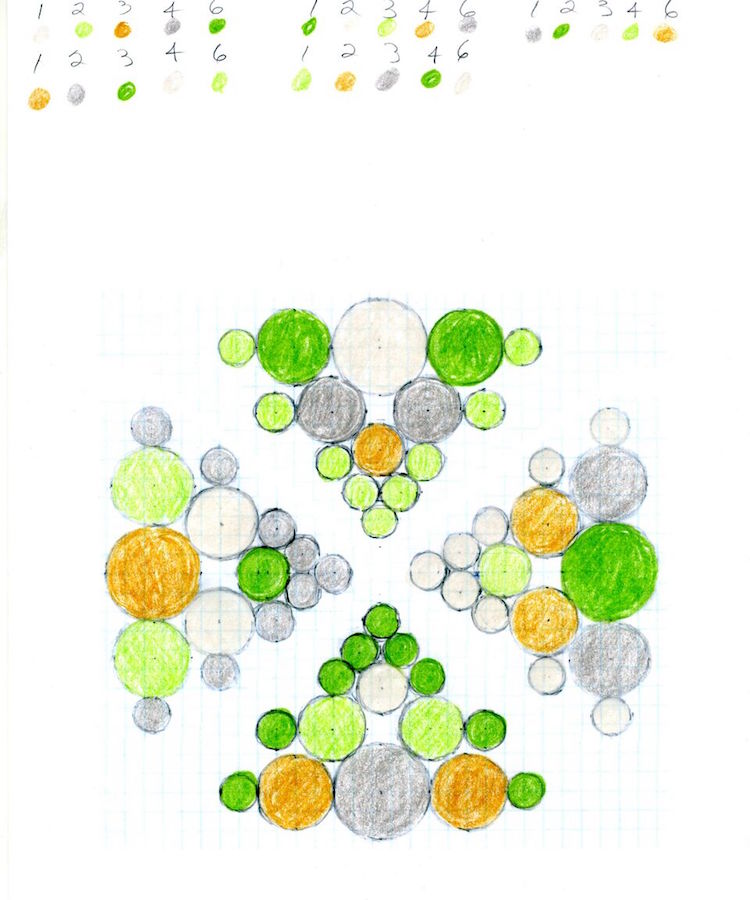

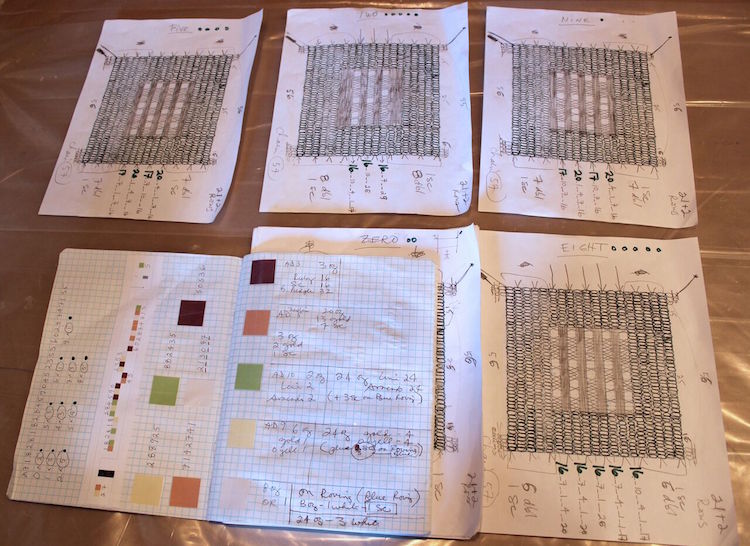

I always begin by working out the basic form of the sculpture on gridded paper, usually in 11” x 17” or 17” x 22” pad. This is a line drawing of basic shapes that plots sizes, shapes, and their spatial relationship, all created by using numerical values of a specific sequence. In this stage, I work with several sequences until I am willing to commit to one.

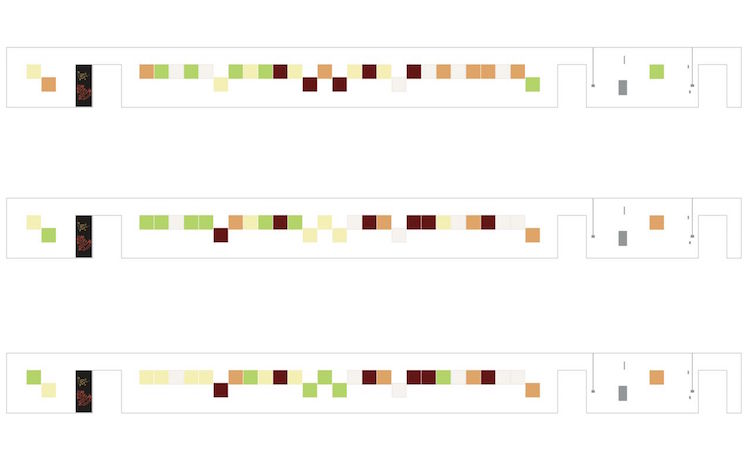

I then scan that drawing and print a couple dozen small copies on regular printer paper which I use to work out different colour combinations, using colour pencils or markers, guided by the same number sequence that created that drawing. Or I drop the scanned line drawing into Photoshop to try different colour combinations.

The method I use depends on how complex or large the group of shapes is, how many variations I want to see, and/or how I feel that day. This step usually takes two weeks.

Once I commit to shapes and colour placement, I paste copies of these visual notes into a standard gridded composition book. Here I work out and keep record of base chain count, stich count, row count, type of stitch, any alteration I make to traditional stitch.

Another aspect of prep work is creating actual material colour samples. For a sculpture with 5 colours, I often make 50 to 60 fiberglass samples, slightly tweaking the resin colour formula. I keep all of the colour trial notes in my book so that I can use the rejected samples for future works. Once I find the right resin colours, I begin crocheting the new work.

Crocheting for days on end

Tell us about your process from conception to conclusion.

First, I develop a system of using the value of each digit from a specific number sequence from pi or e, or by using Pascal’s Triangle as a structure. I then use this system to design the form and colour sequence. This first-step prep-work is described in more detail above in the previous question.

Next, using the continuous fiberglass roving, I crochet flat geometric shapes, utilizing traditional crochet forms and stitches. My go to book is [easyazon_link identifier=”B000X68VT8″ locale=”UK” tag=”wwwtextileart-21″]The Harmony Guide to Crocheting: Techniques and Stitches edited by Debra Mountford.

Now I move the work to my well-ventilated studio space dedicated to the fiberglass work. This is the stinky, toxic part. I use gravity instead of a mold so now I build a jig for draping and forming. I pour out the polyester resin, normally between 8 to 16 ounces at a time; add colour in form of dyes made specifically for this resin; add hardener; mix, and apply resin with a 1” or 2” brush.

The fully soaked crocheted cloth is now a heavy wet lump. I hang this shapeless lump on the jig and recover its shape by gently pulling out the edges until it starts to set. From the time I stir in the hardener, I have between 15 to 35 minutes before I need to walk away. Full cure takes 24 hours.

The fiberglass forms are now hard. This is the really messy part. Using a Dremel tool, I cut into the form, around the loops and knots created by the crochet, in order to clean up the edges and/or to correct scale if too large. I then hand sand all the cuts, all uncut edges, and the front and back sides of the entire form.

Next, the clean fully-sanded form gets recoated with colored resin, often in 2 or 3 coats. After resin sets, any drips that got by me get sanded down. That sanding gets a thin resin touch up.

Final step is the assembly. All current math-generated fiberglass works are created by fusing together large, medium, or small finished units to form larger blocks or panels. I use cable ties to temporarily attach the finished components; attach parts together with the fiberglass roving; apply resin to joints; sand; recoat.

Final obsessive act. These pieces are wall based. They get attached to wall with normal all-purpose screws driven through the work, using holes created naturally by the crochet. In order to camouflage the hardware, I colour the screw heads with markers.

What environment do you like to work in?

Fiberglass work is a labor intensive, toxic, messy process most of which I do standing up and slightly bent over, covered in one sort of protective gear or another, accompanied by semi-loud exhaust fan and even louder music that ranges from medieval music and Bach to Korn, Ministry, and Rammstein. This happens in a dedicated studio space which is a separate building across the courtyard from the coach-house which is our home.

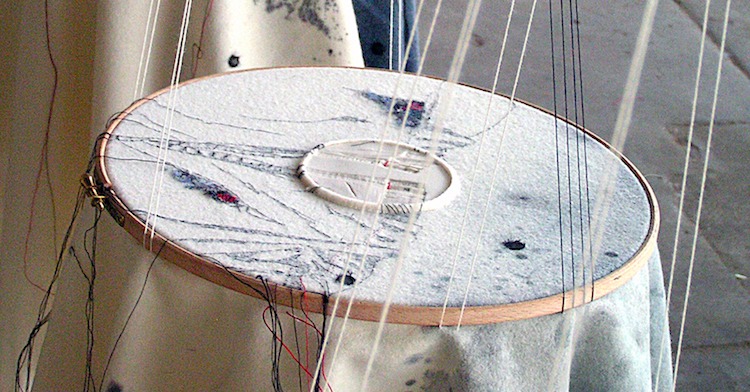

It is at the home’s dining table that I work on preliminary drawings and plans for the sculpture and on the sofa, protected by an old sheet, that I transform the continuous-fiberglass gun-roving into crocheted cloth, often accompanied by family dog.

For years I listened to books on tape and then on CD while I crochet. Now I find shows on Hulu on my computer that I can listen to. Basically, I like for someone to read me stories while I crochet for days on end.

Who have been your major influences and why?

Eva Hesse in her tenacity of material experimentation and exploration, in her use of multiples; and the way she accessed the truth of the language of her materials.

Sol LeWitt in his logic, his geometry, the way he designs systems for the creation of his wall drawings, the way he accesses truth within his systems, his systems which are a list of constraints for specific compositions.

Daisy Chain

Tell us about a piece of your work that holds particularly fond memories and why?

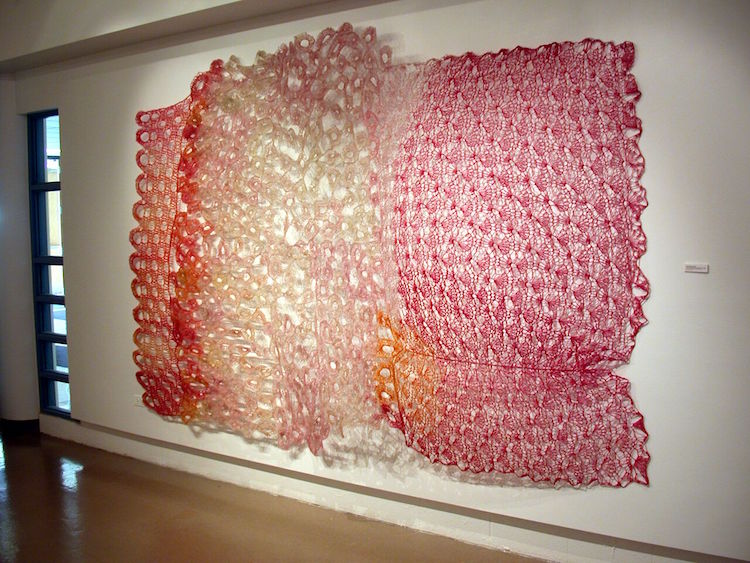

This is a very old piece. Before I started crocheting the roving, I worked with prefabricated fiberglass matt. During the beginning years of crocheting, I made a few pieces that had a foot in both, specifically for a solo show at the Chicago Cultural Center which I began working on immediately after returning from my first trip back to Czech Republic as an adult.

During that trip, I visited my aunt and her family in Martin, Slovakia. I spent summers with her when I was 5 and 6 years old. They still lived in the same apartment. The grounds the same, plain grass blocks covered with yellow dandelions. Immediately we both remembered how we sat together and weaved dandelion wreaths. I took this memory and a highly emotionally charged state of mind and dragged it over my conceptual agenda which back then was still narrative based, and made Daisy Chain.

Daisy Chain consists of 11 skirt forms. For the skirt forms, I bought a couple of different patterns for toddler-sized skirts which I sewed in heavy upholstery vinyl. I stuffed the vinyl skirts with newspaper to make them stand and used them as molds by casting fiberglass matt over them. The straps and bibs that extend from the skirts are crocheted fiberglass that wraps or weaves together to create a wreath, in two solid parts.

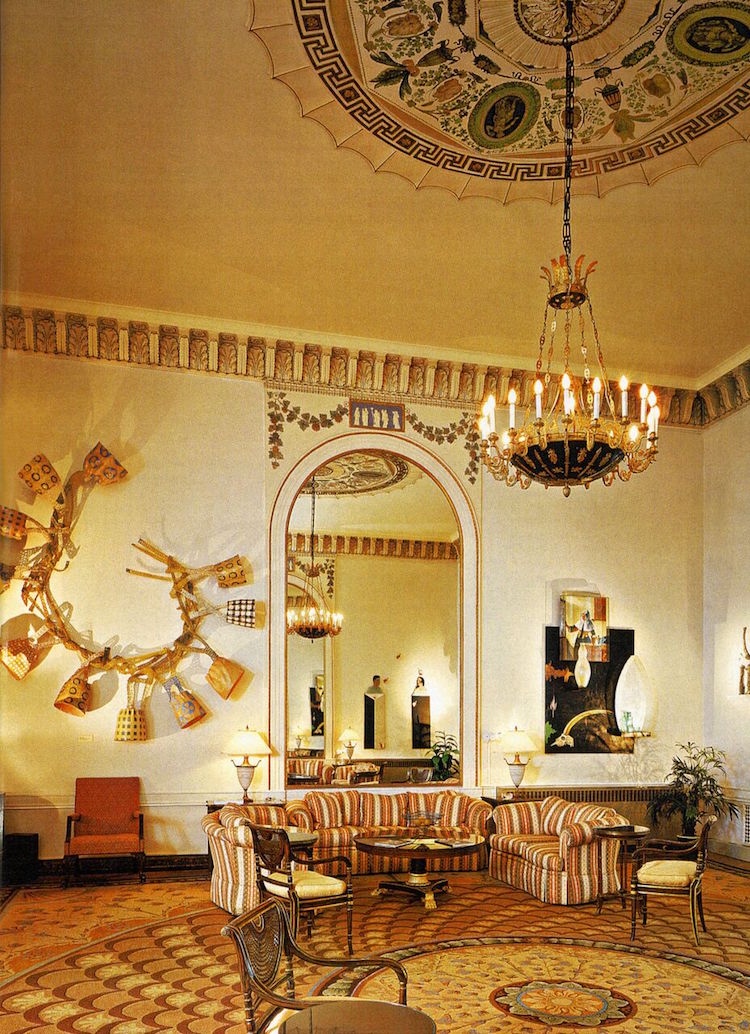

The full sculpture is 112’’ x 116” x 17”. Created in 1999, it was in a group exhibit from 2002 to 2006, as part of the Art in Embassies Program, at Spaso House, the American Embassy in Moscow.

A significant journey

How has your work developed since you began and how do you see it evolving in the future?

I was born in communist Prague. We moved to the United States seven weeks before my 11th birthday. I don’t remember any experience with lace or crochet. In 1999, 30 years later, my Mom and I went back to Prague for the first time. By this time, I was crocheting fiberglass for about 3 years, the forms were on the large end of medium, I was not yet handling the material in the best way, I only used simple stitches, and my identity concepts were still limited.

The trip back home had a significant impact on my studio. What I saw was that Czechs are known for, and are proud of, the best beer on this planet, Czech crystal, and lace!! I, for the first time, realized that Czechs have a tradition of gorgeous lace everything. Every home we visited was inundated with lace: concentric circles on interior door glass; lace curtains; plastic lace on plant pots; lace runners; basically lace everywhere.

On the streets, the old ladies seemed to have a sort of uniform which consisted of four items: blouse, slacks or skirt, vest, and shawl. Three of these were usually in an over-all pattern, the fourth was solid. This overload of patterns should not have worked but it did.

When I got home, my work exploded. Somehow, recognizing that my heritage comes with a lace tradition, I felt a permission to exploit it more fully. I also realized that, although I was claiming to articulate narratives of identity in the language of crocheted fiberglass, I was not utilizing the fullness of the crochet language.

I bought a book that catalogs many of the traditional stitches, patterns, and formats and began to exploit this resource more fully. I learned that the more complex stitches created a stronger form and allowed me to work larger.

While immersing myself in pattern, I finally began to think outside of the body and saw identity in terms of pattern: internal and external; nature vs. nurture; DNA; social behavior, how groups affect the individual. The identity dialogue evolved into greater complexity. The sculptures reached their proper large scale. Reaching this scale forced me to develop better handling of the material. All this happened because I went back to Prague, saw lace, and reconnected to that culture and place.

From about 2000 on, most of the work was large, in one piece and limited by standard doorways in the short dimension. The next significant change in my work was an introduction to math structures.

In 2001, a one-off installation created out of time restriction, introduced a grid, multiples, and used a sequence from pi as a random pattern generator. This use of pi was suggested to me by Tim, my math nerd husband.

Letting the numbers make the work

In 2007, I started working on a solo show for a new, beautiful gallery with a few very large walls. Like a 5-year-old, I see a huge wall and I want to fill it. I planned a 10 by 10-foot square. This meant modules. In the thinking/drawing stage, one thing led to another and I thought: articulate the digits directly; let the number make the work; use the grid as a base structure.

So now, I devise systems for visualizing numerical values by which I can create new and uncommon patterns in which Pascal’s Triangle and/or value of digits from specific sequences define spatial relationships and color distribution. Sequences from pi and e can produce completely different visual and spatial rhythms.

Larger works are straight forward, more obvious, interpretations of each digit, while the source math in the small works is less evident. Math gave the natural organic feel of the crocheted fiberglass a structure that was missing. I used pi, e, and Pascal’s Triangle to create all the work for the DIGITS show at Alfedena Gallery in 2008. Everything since then has been number generated.

Recently, I began exploring new systems of mapping sequences, anchored in drawing with various media such as graphite, markers, acrylic gouache, and encaustic paints on panel and variety of papers. These 2D works range from simple notations as graph plots to complex layered patterns that visualize hundreds of digits.

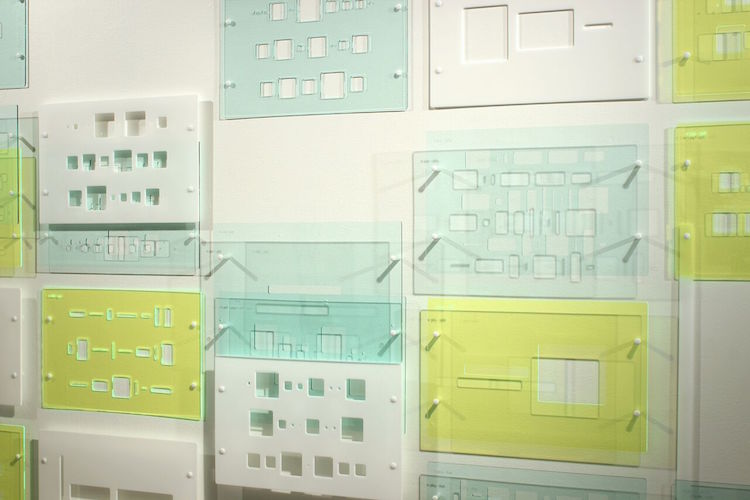

The very last group of works I created consists of multiple laser-cut acrylic-sheet tablets.

Can you recommend 3 or 4 books for textile artists?

Two inspirational exhibition catalogues. [easyazon_link identifier=”3791353829″ locale=”UK” tag=”wwwtextileart-21″]Fiber: Sculpture 1960-Present by Jenelle Porter

[easyazon_link identifier=”B01K3HBFVC” locale=”UK” tag=”wwwtextileart-21″]Tradition Transformed: Contemporary Japanese textile art & fiber sculpture which has multiple authors including Sheila Hicks, Masakazu Kobayashi, and Naomi Kobayashi.

Also, Influence and Evolution: Fiber Sculpture…then and now by Ezra Shales and Rhonda Brown.

What piece of equipment or tool could you not live without?

My inner child says: the numbers pi and e, the grid, and my curiosity. My inner adult says: a battery powered full face respirator.

For more information visit: www.yvettekaisersmith.com

Got something to say about the techniques, materials and processes used by this artist – let us know by leaving a comment below.

Comments