Willemien de Villiers is a South African artist and writer, currently residing in Muizenberg, Cape Town.

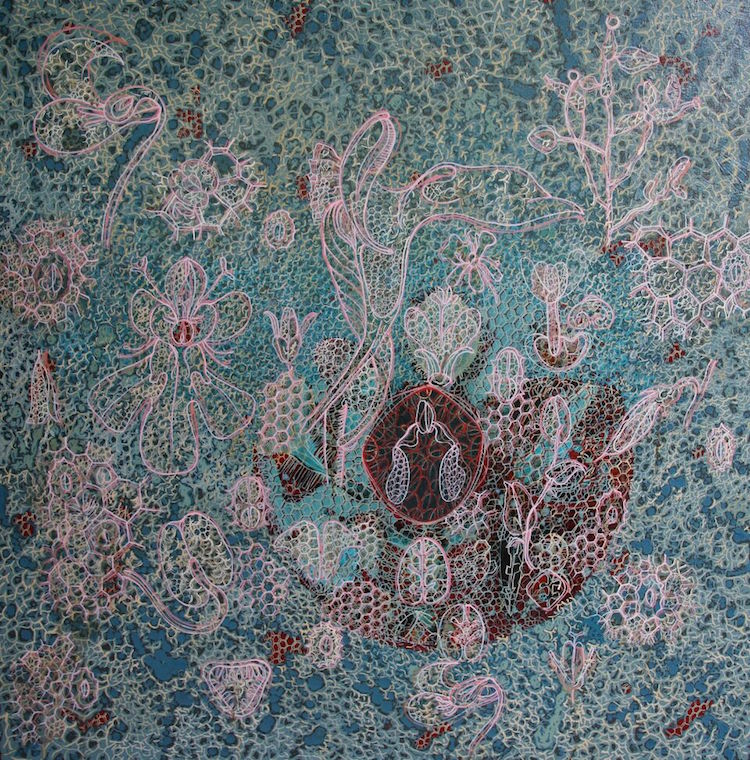

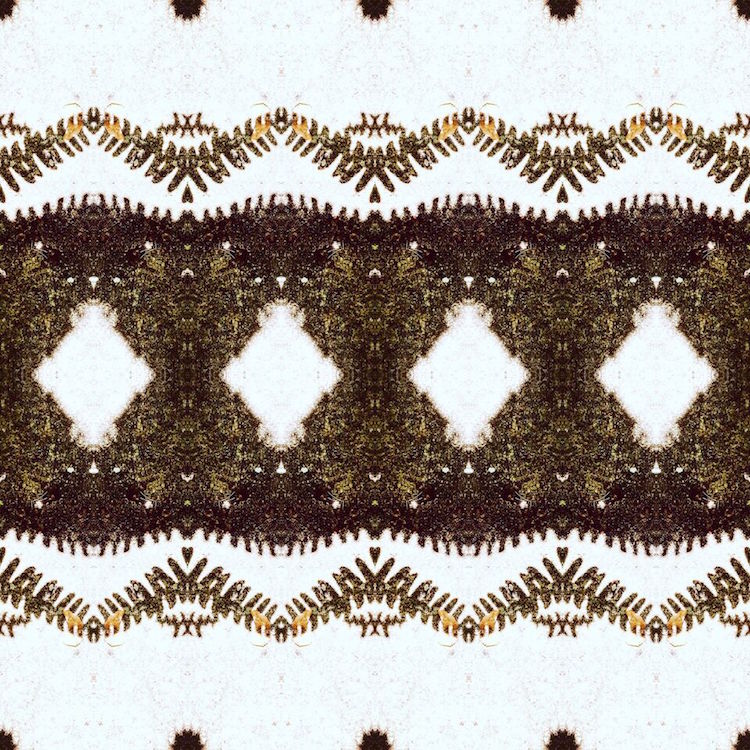

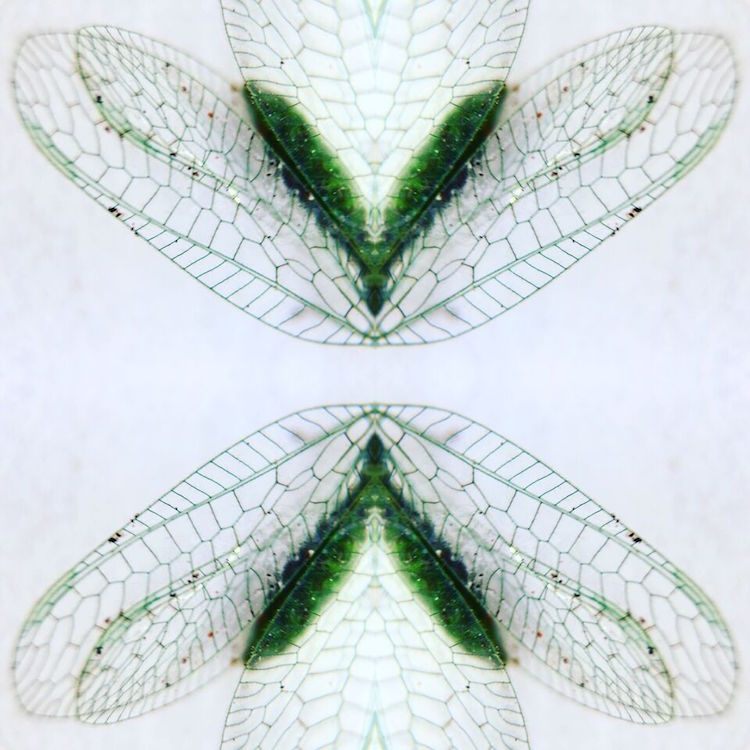

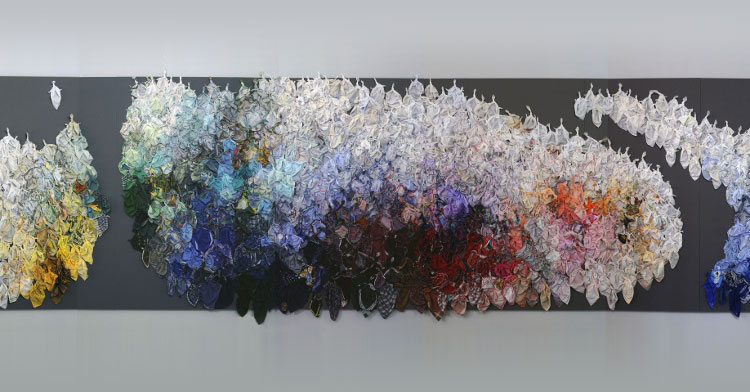

Her work is a dialogue between real and imagined microscopic biological phenomena, reconstructing the common cellular history of all living things through atomised patterning. The process of decay and disintegration, and the inevitable new growth and integration that follows inform this major theme in her work, especially with regard to memory, personal, political and social.

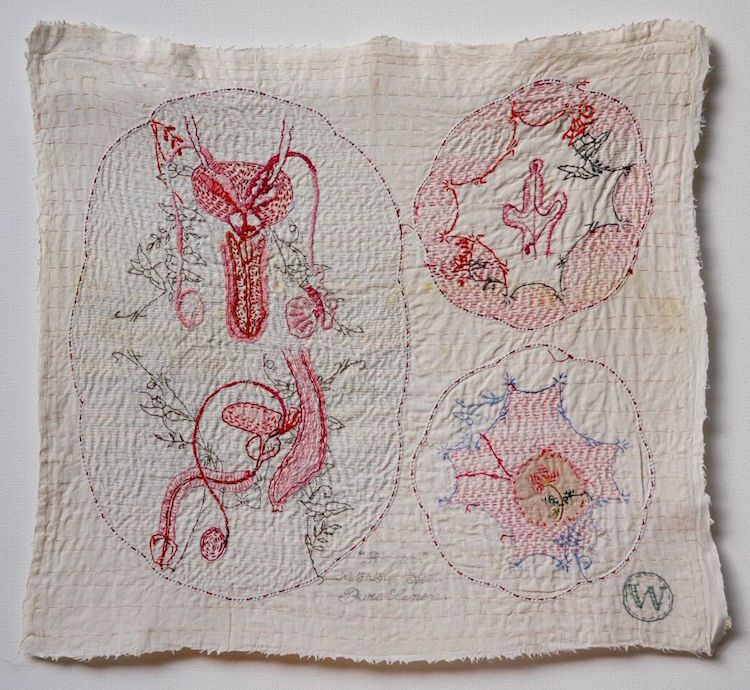

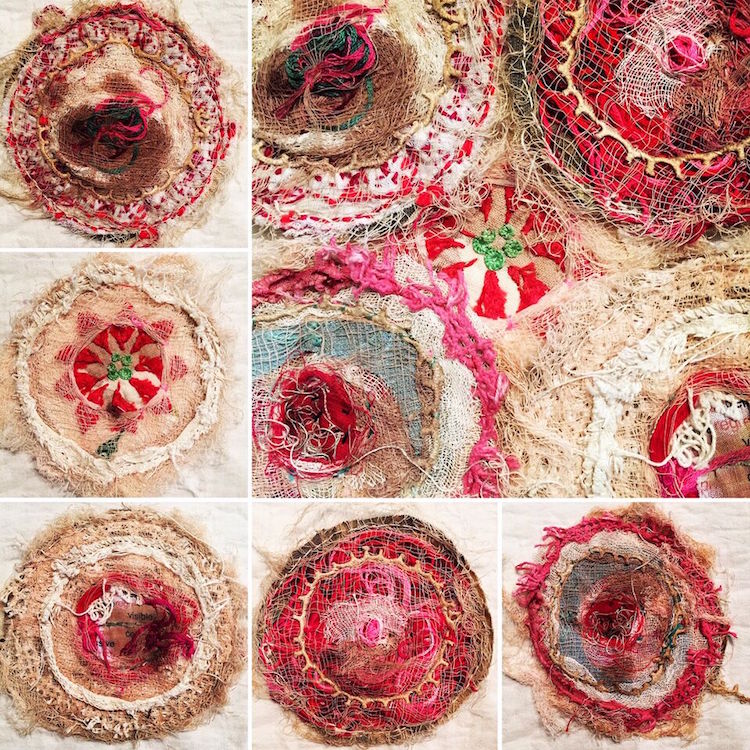

For her stitched works, she uses vintage domestic textiles, like doilies, tray cloths, tablecloths that show a lot of wear and tear, with a sense of previous lives, or narratives to work with.

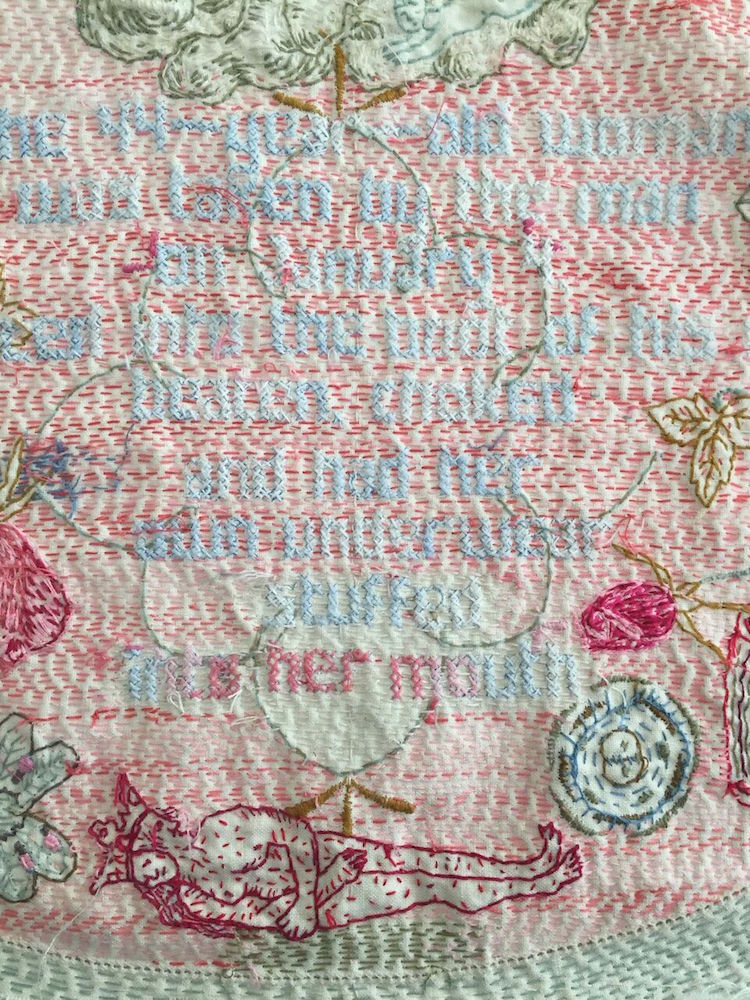

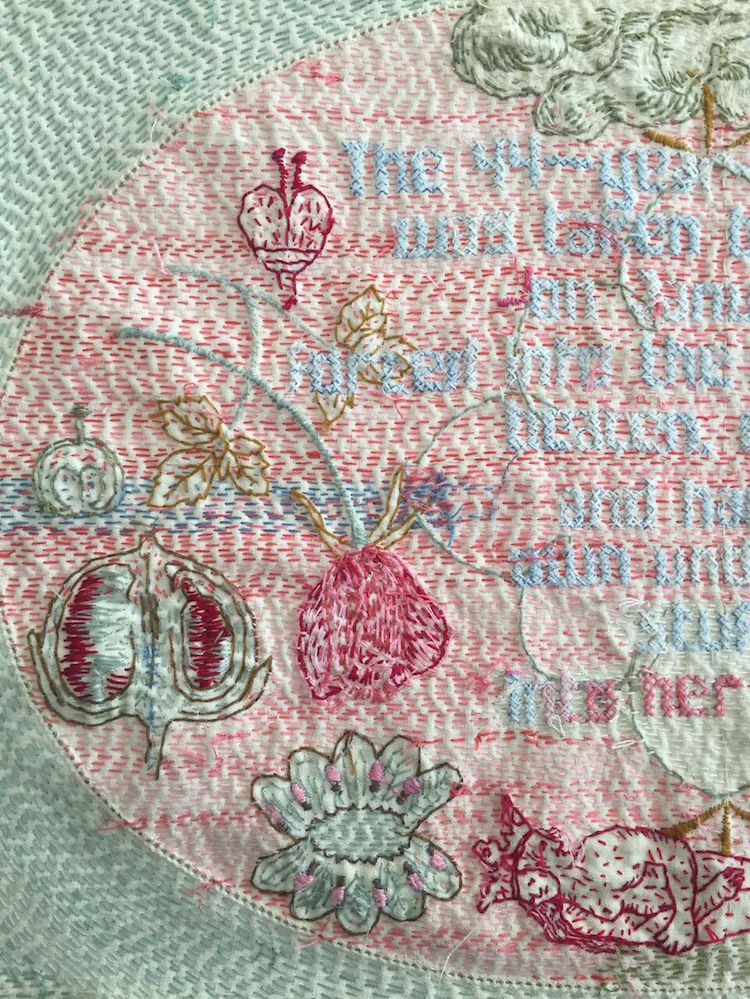

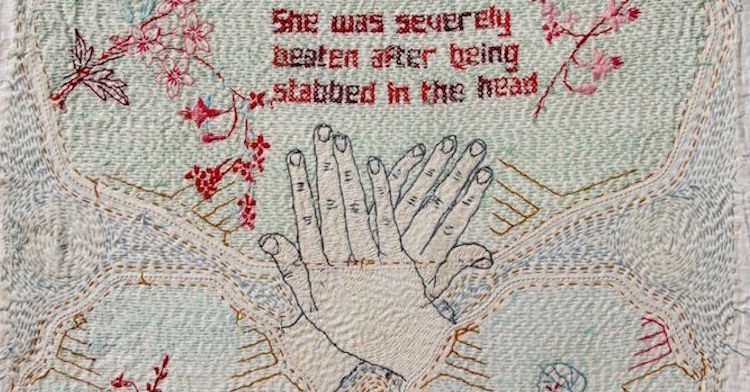

Domestic violence, all violence against women, is a recurring theme.

Willemein has admired the 62 Group of textile artists for a long time and is very pleased to have been selected as a new member. She is looking forward to exhibiting alongside such esteemed and funky contemporary artists.

In this interview, Willemien tells us about her route to becoming an artist and how her dark subject matter translates to textiles.

An inborn love of fabrics

TextileArtist.org: What initially attracted you to textiles as a medium?

Willemien de Villiers: I have a degree in Fine Arts from the University of Pretoria, Gauteng, South Africa, and as a student, I focused on printmaking: silkscreen printing, etching, litho.

I’m drawn to the idea of repeats; of multiple images of the same thing and was lucky to start my working life as a designer at a textile printing company, where I analysed and adapted samples from Europe and the US to suit the South African market.

Back then, almost 40 years ago, everything was done slowly and by hand. It suited my personality to work that way – work as meditation. During that time, I also screen-printed my own range of fabrics.

But apart from an inborn love of fabrics, there really is nothing as sublime as the smell and texture of pure cotton and linen, I only considered it as a medium for art making a few years ago.

And, more specifically, how was your imagination captured by stitch?

Sewing, by its very nature, creates a repeat pattern, stitch after stitch after stitch. I suspect that I find this practice so soothing because every living thing on this planet owes its existence to an endlessly repeating cellular echo that generates and supports the equally endless cycle of life and death.

All over Africa, cloth is used to express beauty, to tell stories and to record history. Growing up, I was surrounded by European-style crocheted doilies, beaded milk jug covers and hand embroidered tea tray cloths, whose bucolic images stirred, but never truly captured, my imagination.

Only much later, as a young adult, I came into contact with the rich and vast variety of African textiles: my first glimpse of a woven Kente cloth from south Ghana led to a lifelong love affair, especially when I dug a bit deeper into the meaning of the colours used: black for intensified spiritual energy, blue for peace and harmony, green for planting, harvesting and spiritual renewal, pink for the female essence of life, etc. etc.

Bogolan (‘made from mud’), the exquisitely patterned cloth from Mali, is another constant point of reference and inspiration, with its bold patterning and organic earth connection.

When I first came across the appliqued flags of the Asafo, the warrior group of the Fante people of Ghana, their colourful exuberance blew my mind. I always feel creatively stimulated when I spend time studying them; constantly learning more and more about the various messages and meaning of each vibrantly executed flag or banner.

All over South Africa, you’ll find embroidery co-ops, where (mostly) women tell their stories, using needle and thread. Kaross, founded by Irma van Rooyen and situated in Letsitele, Limpopo province is an inspiring example. Mogalakwena, in the Waterberg District of Limpopo province, South Africa, is another, where founder Elbé Coetsee facilitates the making of beautifully embroidered ethnographic textiles.

A need to connect

What or who were your early influences and how has your life/upbringing influenced your work?

I was born and raised in Apartheid South Africa and grew up very isolated from the rest of the world. I think the strict rules of ‘us’ and/vs ‘them’ stirred in me a need to connect; to unify. It’s ironic because I’m an outsider by nature. An observer on the fringe. Perhaps that’s why I find molecular images of anything, but especially plants, so soothing and inspiring. The more up close you get to anything, the less difference there is between ‘you’ and ‘them’.

As a survivor of childhood sexual abuse, I’m sensitized to any form of abuse, especially that of women and children. A lingering effect of abuse, sexual or otherwise, is a sense of disconnection, and I’ve found it very helpful to integrate my thoughts and feelings into my embroideries. The very act of stitching is healing, in that it allows chaos to transform into a calm order.

To highlight, and start a conversation, around the global issue of gender-based violence, I cross-stitch snippets of actual police reports onto the previously mentioned pastoral scenes, often found on tray cloths, etc. I aim (but don’t always succeed) for a subtlety; I want to draw the viewer in and up close to engage with the work and the message. You can read more about this here.

What was your route to becoming an artist?

The formal route was studying fine arts at university level, but informally I’ve been drawn to colour and pattern from a very young age. I’ve always been happiest when my hands are busy creating something, as long as it’s not baking or cooking.

Tell us a bit about your chosen techniques.

My immersion into stitching on domestic textiles is a fairly recent development. Before then, I painted full time; oil on canvas. My paintings are very detailed, with images and patterning built up as multiple, semi-transparent layers.

Feeling the need for something more textured and tactile, I started stitching on my canvases. This led, over a few months’ experimentation, to bypassing the painted canvas, and stitching straight onto found, in charity shops, damaged and stained domestic textiles, like tray cloths, napkins, tablecloths.

How do you use these techniques in conjunction with embroidery?

I’ve never lost my love of printing techniques, and often block print random patterns onto the cloth, to create visual texture and a sense of layers, before transferring image/s to stitch.

How would you describe your work and where do you think it fits within the sphere of contemporary art?

I work from a deeply connected place of not-knowing if that makes sense. I do what I do because I have no other choice.

An organic process

Tell us about your process from conception to conclusion.

Artists are never off-duty. I’m always looking, absorbing, processing information. Before starting something new, I slowly look through my substantial pile of cloths, until I find one whose texture, particular stains or something else catches my imagination. I usually choose a few; in fact, I always work on more than one piece at any given time.

I’ll then flip through my collection of images and photos to find a visual framework for whatever I’m thinking or feeling at the time. It’s an organic process, with stops and starts. I need to build up some kind of a relationship with the cloth before I actually start stitching.

I (wo)manhandle it quite a bit – scrunching up, staining, printing, tearing, sometimes burning. This ritual marks the passing of the cloth to me, releasing it from its previous history. I prefer to work on the reverse side of the cloth, thereby creating my own ‘front story’, and relegating the previous embroiderer’s work to a ‘back story’. Back stories are vitally important, and I often scan the reverse side of my finished works, and print them on high-quality art paper, to be sold as works in their own right.

I describe my process in more detail here.

What environment do you like to work in?

Quiet, indoors. Preferably my studio.

What currently inspires you?

Germinating seeds. Growing things from cuttings. Bulbs. All things botanical, with its hidden life force that reveals itself when the time is right. It’s an antidote to the general ugliness of the world today.

I’m inordinately proud of a seven-centimetre high jackfruit tree I managed to grow by germinating a seed I brought back from India.

The Mysteries

Tell us about a piece of your work that holds particularly fond memories and why?

The first large work I stitched happened almost by accident. I found a heavy linen tablecloth at a local charity shop, covered with beautiful stains. They immediately suggested something medical … viral? bacterial? and I compulsively worked on it until, a few weeks later, it was done.

While stitching, I felt connected to something I couldn’t name, so I called it ‘The Mysteries’. I used a lot of mathematical imagery, as well as microscopic images of various viruses, e.g HIV, measles, and polio.

A random visitor to my studio bought it before it was even finished, it immediately spoke to her, as a medical doctor and researcher at the coalface of HIV mother-to-child transmission. She understood ‘The Mysteries’. It now hangs in her research facility in Johannesburg, among other hand-stitched cloths made by local craftspeople.

What advice would you give to an aspiring textile artist?

Don’t overthink. Just do it.

Can you recommend 3 or 4 books for textile artists?

[easyazon_link identifier=”1848852835″ locale=”UK” tag=”wwwtextileart-21″]The Subversive Stitch : Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine by Rozsika Parker. A classic, must-read.

[easyazon_link identifier=”0262122901″ locale=”UK” tag=”wwwtextileart-21″]The Object of Labour . Art, Cloth and Cultural Production. Twenty thought-provoking essays that explore the personal, political, social and economic meaning of textile work. Edited by Joan Livingstone & John Ploof

[easyazon_link identifier=”014103579X” locale=”UK” tag=”wwwtextileart-21″]Ways of Seeing by John Berger

[easyazon_link identifier=”1849942994″ locale=”UK” tag=”wwwtextileart-21″]Slow Stitch : Mindful and contemplative textile art by Claire Wellesley-Smith

What other resources do you use? Blogs, websites, magazines etc.

I take loads of photographs to use as reference, but also source images online. I find medical and botanical images from the 12th to the 17th century especially beguiling.

What piece of equipment or tool could you not live without?

Embroidery needles. I have a few favourites, curved from overuse, and about to snap. An over-the-knuckle thimble I repurposed from a vintage chamois leather glove – possibly the inside of a cricket catcher’s or fielding mitt. My apple green thread-snipper I bought in India. Sharp pencils and a good pen. Blue carbon paper.

For more information visit: www.willemiendevilliers.co.za

Let us know what your favourite aspect of the artist’s work is by leaving a comment below.

Comments