Bridget Bailey is known for her intriguing ideas, observations and very particular skills with materials.

Over a career spanning almost 4 decades, Bridget has created pleated scarves for Liberty, designed and made hats for many clients including Jean Muir and Saks Fifth Avenue, and brought her Pea pod jewellery to the V&A. She has also developed an international reputation as a teacher over the last 10 years.

Besides all this Bridget says her greatest achievement is somehow managing to change and evolve and find ways of being relevant over her 35 years of making. If only there was an award for that!

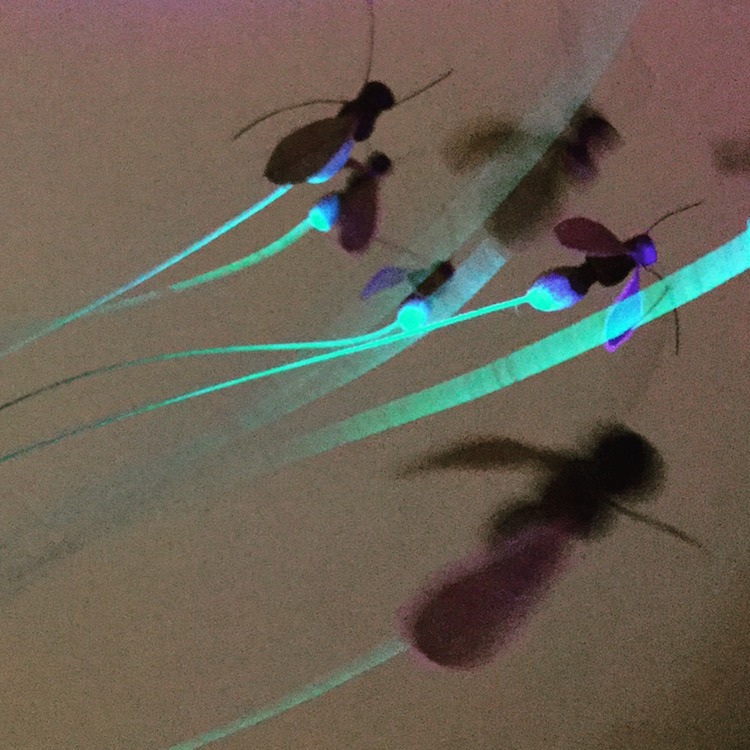

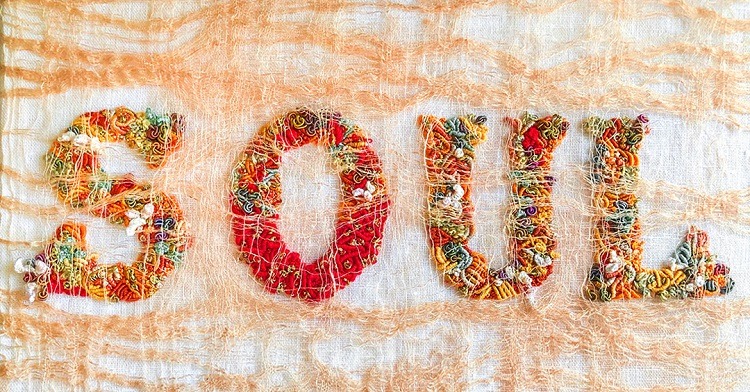

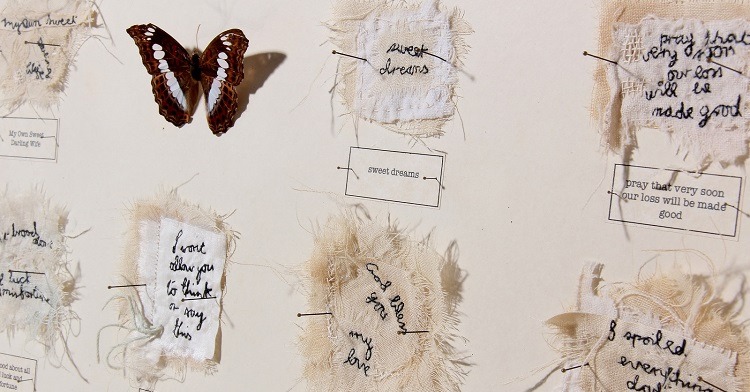

In 2017 Bridget opened her first solo exhibition entitled Absolutely Buzzing. This exhibition about insects offered the chance of an investigative making-challenge at Inspired by… Gallery, in the North York Moors National Park.

In this interview, Bridget describes the various twists and turns of her career in, amongst others, the disciplined art of millinery. We discover what led her to a more experimental way of working and why the north Yorkshire moors have provided a life time of inspiration.

From dead bees to cat’s whiskers

TextileArtist.org: What initially attracted you to textiles as a medium?

Bridget Bailey: I really noticed textiles when I was on my foundation course in Scarborough. My mum was a painter and my sister is a potter, but the qualities of textiles were so different and exciting and had so much variety that I was hooked.

And, more specifically, how was your imagination captured by stitch?

Actually, it was pleating that first captivated me. I did a BA in textiles at Farnham College of Art where I became fascinated by the way fabric could become three-dimensional. It’s in my dictionary of techniques and I still use it.

What or who were your early influences and how has your upbringing influenced your work?

I grew up in Sandsend in North Yorkshire and spent lots of time in on the moors looking for weird and wonderful caterpillars, or beachcombing for shells. My elder sisters were always better at finding things than me, and I developed a passion for nature and collecting, maybe as a way of trying to catch up.

We were always encouraged to do creative things and mum was always drawing and painting. She was also a passionate gardener and kept some hens and turkeys with beautiful feathers. I still have a hoard of them tucked away and collect many other oddities, from dead bees to cats’ whiskers.

What was your route to becoming an artist?

I’ve only really been heading towards becoming an artist over the last 10 years. From a background in textiles and a long career in millinery, as a co-founder of Bailey Tomlin Hats, it’s taken me some time to find what I want to say with my work – when there isn’t a customer to please, a colour to match, or a big order to get out.

There have been a few turning points, but a recent and notable one was ‘In Conversation’ in October 2016, an exhibition with Emily Jo Gibbs, where we explored what it means to collaborate. We really did have a conversation in making, and it was fascinating to see our differences, and it was very revealing how we think and work.

I noticed the difference that responding and replying to something can make, and I’m able to work in that way on my own.

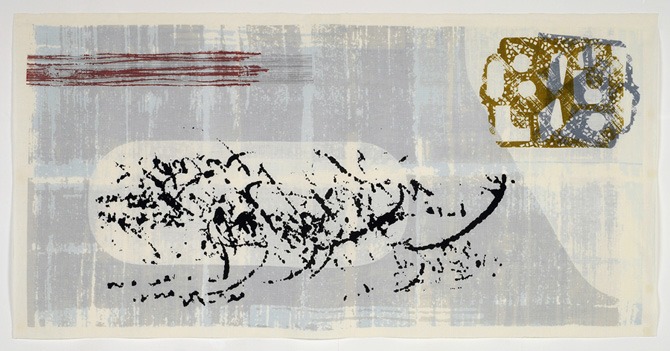

Tell us a bit about your chosen techniques.

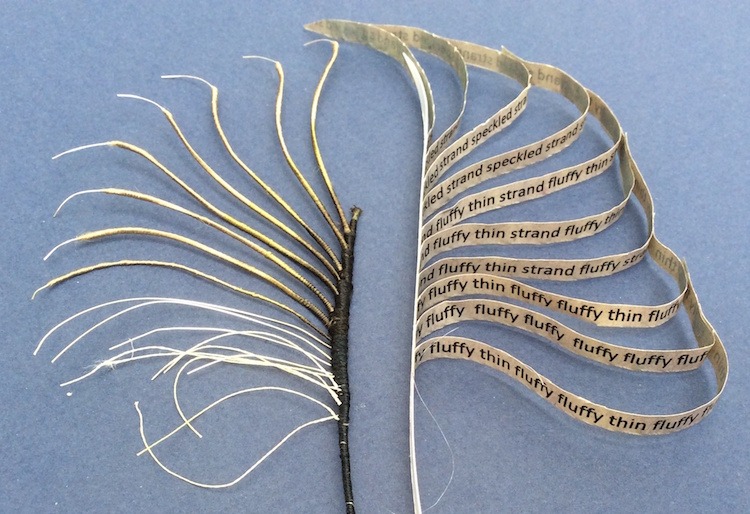

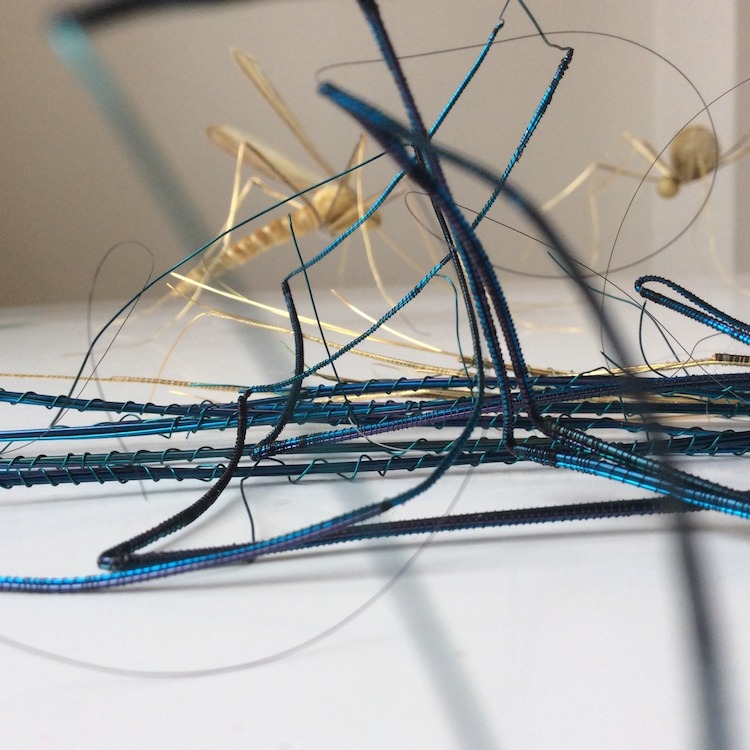

I love the effects I can get by binding wires with different threads.

Painting and dying with dyes.

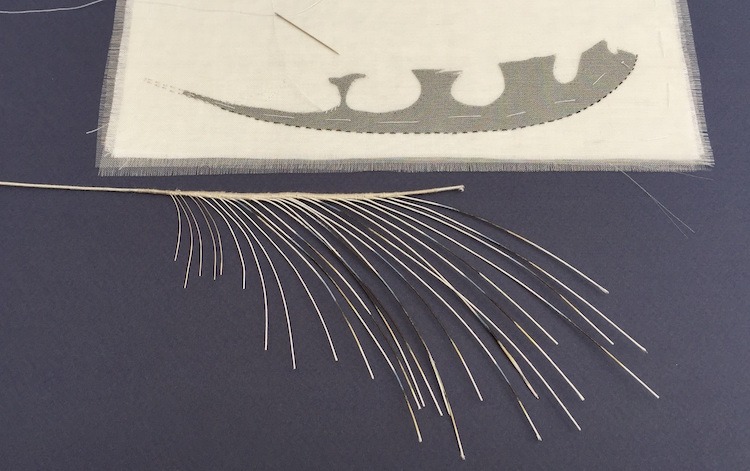

Fraying and manipulating fabrics.

Using millinery techniques to make curved rolled edges or sharp straw thorns.

Embossing and wiring silk to make petals.

I’m tinkering with a book about tying fishing flies at the moment.

A sort of textile Darwin

How do you use these techniques in conjunction with textile taxidermy?

I might make a spider’s legs hairy by binding on frayed silk organza, or wrap the legs of a fly with threads of peacock feather. Embossed velvet is very like a dusty butterfly wing already, especially with a few tiny snips of turkey feather added on top.

How would you describe your work and where do you think it fits within the sphere of contemporary art?

Investigative Textileism, Textile Taxidermy, Entomological millinery. I find it hard to describe, it’s a blend of all these things. I’d love to be thought of as a sort of textile Darwin, exploring nature and recording and translating what I learn into materials and making.

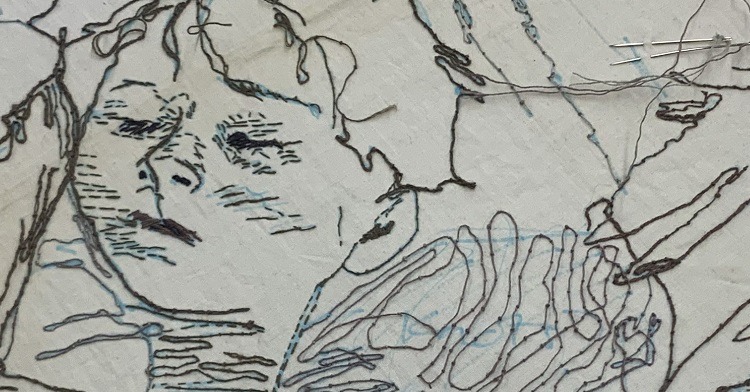

I’m beginning to see a new direction for my work where I’m putting a spotlight on this experimental stage of making. My most exciting ideas happen when there aren’t the restrictions of doing the finished piece, and I’m on the edge of my making ability wondering what will happen.

It’s a big shift for me to think about showing some of this process as well as finished work. I’ve spent many years in millinery where all the experimenting is hidden and everything needs to look effortless.

Do you use a sketchbook? If not, what preparatory work do you do?

I do lots of quick making-experiments, and because things often look better in my mind than when I make them, I need to get that idea out of the way and move on to a better one. Consequently, I have a mass of boxes full of tests and trials and sample bits, sort of like a dictionary of techniques and materials.

That’s one sort of sketchbook, and the other is my iPad, which is bursting with photos of things that inspire me.

Tell us about your process from conception to conclusion.

I have some ideas that I’d love to make, like a crawling spider leg, and I have my ‘making dictionary’ boxes of tests and trials. Every so often an idea finds a match in the ways of making I’ve tried and developed. It’s always delightful when this happens, but there are always so many ideas where it hasn’t happened yet.

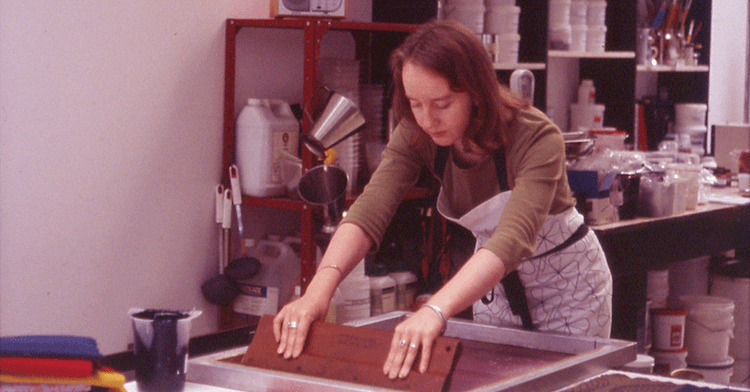

What environment do you like to work in?

I need to make a bit of a mess when I’m experimenting, as I need lots of materials and samples around me. I do my most creative stuff when I can pretend it’s not a problem if it goes wrong. I need to create a stress-free environment by putting on a podcast or some music that can block out all the other things that I should be doing.

Once I know exactly what I’m making, I need lots of daylight as my work is intricate and the making is very intense.

What currently inspires you?

I’ve been doing some research for my exhibition all about insects entitled ‘Absolutely Buzzing’, and, having never studied much science or biology, when I learn something weird about the spots and speckles on butterfly wings or bioluminescence, I’m amazed and it’s all very inspiring.

Tell us about a piece of your work that holds particularly fond memories and why?

The Tipping Teacup and the Spoonful of Sugar were made for Mad for Tea, an exhibition at Fortnum and Mason in 2014. I enjoyed having the opportunity to make something surreal and my push millinery skills to the edge, by blocking a straw spoon.

The tea and sugar spilling out make elegant lines, which makes a piece more flattering to wear.

A dictionary full of techniques

How has your work developed since you began and how do you see it evolving in the future?

Through 35 years of making my pleated textiles, and my millinery career, I’ve concentrated on techniques and the qualities of materials. But now I’m curious about developing a more thoughtful approach to my work.

Making alongside learning intrigues me, and I’m finding it interesting to observe where explaining in words ends and showing with materials begins. I’m always at this point in the intense one-to-one masterclass I teach, and it’s making me think about the relationship between speaking and making.

As I think of my techniques as my dictionary, I’m really working on the things I want to say in my language of making. I’m planning to explore this in some collaborations with writers and filmmakers.

What advice would you give to an aspiring textile artist?

My work develops through the effort of exhibiting it as well as by doing it. Not just because other people see it, but also because it helps me to see it clearly and resolve problems that I might not ever quite sort out. And it’s important to make work that I’m really interested in. I find it easier to promote stuff I’m passionate about.

My artist friends have also been a great help and source of encouragement.

Can you recommend 3 or 4 books for textile artists?

While researching for my insect exhibition I’ve kept returning to these three books:

[easyazon_link identifier=”1782401075″ locale=”UK” tag=”wwwtextileart-21″]The Bee – A Natural History by Noah Wilson-Rich.

[easyazon_link identifier=”1333698577″ locale=”UK” tag=”wwwtextileart-21″]The Salmon Fly. How to dress it, how to use it. by GEO. M.Kelson – a self-publish from 1895.

[easyazon_link identifier=”0712350446″ locale=”UK” tag=”wwwtextileart-21″]Nonsense Botany by Edward Lear.

What other resources do you use? Blogs, websites, magazines etc.

craftcentral.org.uk

selvedge.org

What piece of equipment or tool could you not live without?

Although I use various scissors and needles, if I had to choose, then it has to be my hands…

Do you give talks or run workshops or classes? If so where can readers find information about these?

I offer masterclasses in my particular textile and millinery techniques. I teach these one-to-one at my studio, and can also be booked to teach groups.

Email me and I will send some information: ku.oc.yeliabtegdirb@oiduts and look at my website.

How do you go about choosing where to show your work?

It’s hard to find the right places. There are special exhibitions and galleries a big part of the effort is getting them to notice. I find chatting to my artist friends very helpful too.

Special work needs a special audience and I try to visit shows myself and see the work and chat to people there.

Where can readers see your work this year?

MADE LONDON – Marylebone, 19th – 22nd October 2017.

For more information visit: www.bridgetbailey.co.uk

Let us know what your favourite aspect of the artist’s work is by leaving a comment below.

Comments