Tapestry has been practised across the globe for thousands of years. Ancient Egyptians and Incas used tapestries as burial shrouds, while the Greeks and Romans used them as wall coverings in public buildings. The Chinese preferred to use them to decorate clothing or wrapping gifts.

But what exactly is a tapestry? Looking at these five artists, you’ll be hard-pressed to say.

While each of them uses traditional techniques, they’ve added their own approaches to subjects and materials in ways you wouldn’t expect.

Frances Crowe creates tapestries representing significant battles, but they’re not the types of scenes you’d expect. Fiona Hutchison works with plastic and other unusual materials, while Wendy Carpenter embeds surprising found objects in her work. Jeni Ross weaves modern abstract designs with colours and shapes that pop. And Molly Elkind brings tapestry work down to size by creating small, but mighty, weavings.

If you’ve not explored tapestry work before, now’s the time.

Frances Crowe

Tapestry activism

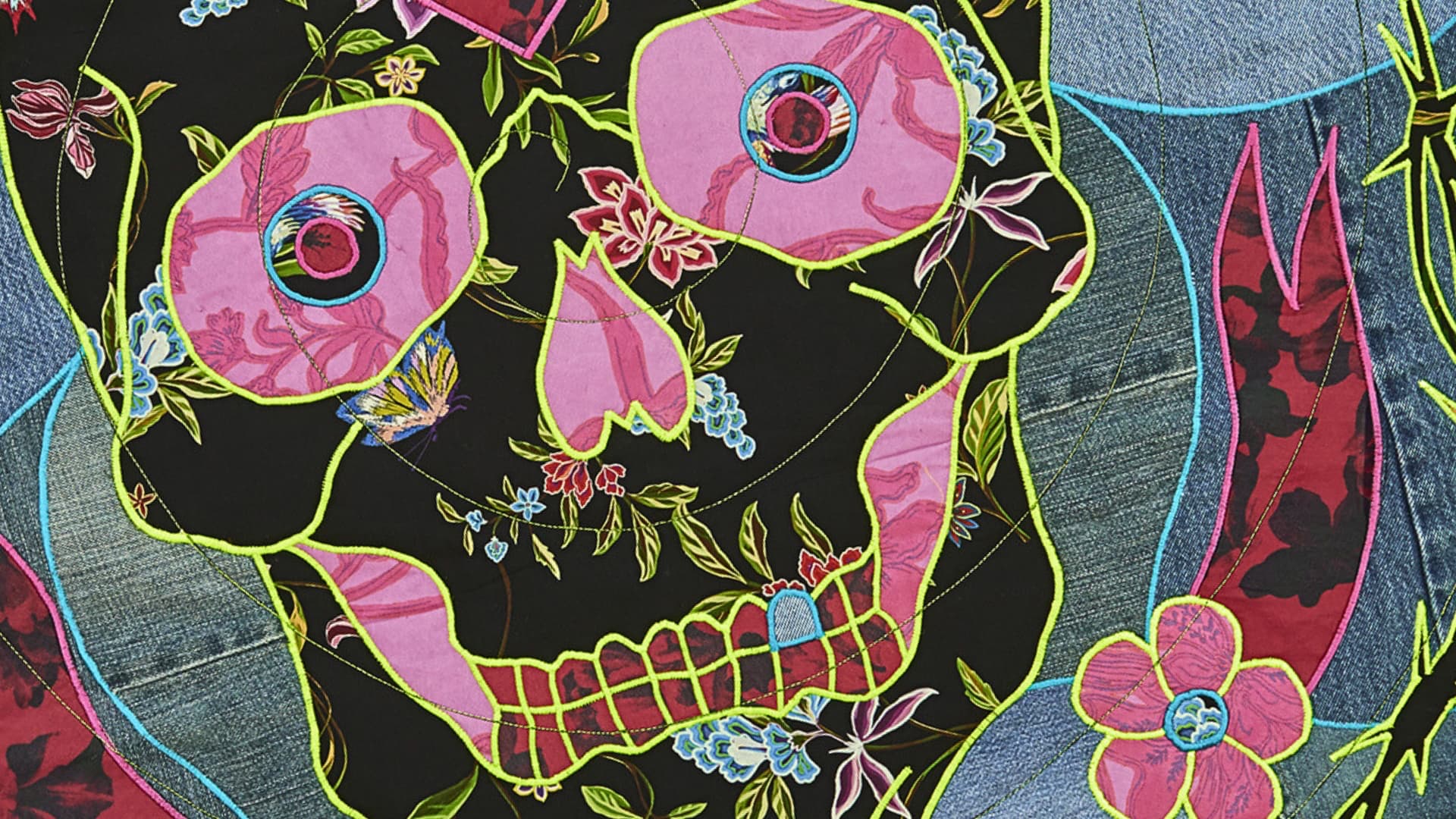

As a grandmother, Frances Crowe was appalled by TV news images of children being taken from their parents and put into cages after crossing the Mexican border into America. Around the same time, the story of the ‘Tuam Babies’ broke in Ireland. It was discovered hundreds of babies had been buried in a mass unmarked grave near a home in Tuam, County Galway.

Frances decided to channel her outrage into creating Torn Apart to explore the human experience of intersectionality, inequality and social justice through family separation.

‘I used a media image of a family walking together as my starting point. I imagined them being separated and the little boy losing his shoes. I sought to create characters that could represent any race at any time in history. And for the boy’s shoes, I decided to feature the most popular branded and expensive sneakers available at the time.’

After sketching the family unit, in an unexpected move, Frances ripped the drawing in half. The torn edges were striking, so she decided to weave the tapestry in two parts and leave the horizontal warp threads exposed to represent the fragile threads that bind families.

Frances used her homemade scaffold frame loom, and the cotton warp was wound 10 ends per inch instead of creating a shed. One section was woven on the front of the loom and the other on the back using the same warp.

‘I use handwoven tapestry to share narratives of global issues because of the time spent with the warp and the weft. One large tapestry can take months, or even years, to weave. Being still during moments of creation allows me to process an issue at hand, be it migration, global warming or other crisis that bothers me.’

Frances discovered the weaving department at Dublin’s National College of Art and Design during her teaching practice year where she studied with Evelyn Lindsey. And for the past 40 years, tapestry has been Frances’ ‘friend and companion’ supporting her in good and not-so-good times.

‘I have woven almost every day all these years. It’s the most immersive and mindful way to live my life. I also believe handwoven tapestry supports my message because cloth is something everyone can relate to. Even though an image may be disturbing, it can prompt important conversations.’

Frances Crowe is based in County Roscommon, Ireland. Her tapestries have been selected for a variety of fibre art exhibitions in Ireland, England, China and Canada. She has also received many awards, most recently An Agility Award from the Arts Council of Ireland. She has also been selected by The Michelangelo Foundation for inclusion in the Homo Faber guide for Master Artisans.

Artist website: francescrowe.com

Facebook: facebook.com/fcrowetapestry

Instagram: @crowefrances

Fiona Hutchison

Weaving with plastic

Fiona’s passion for the sea is immediately apparent in her work. But she also has a mission to expose global water challenges by incorporating the very materials that threaten their health.

‘I don’t want to create a representation of the seas and oceans. I want to make something that’s experienced and fosters a deep personal connection. I want to create a dialogue among the subject, materials and the viewer.’

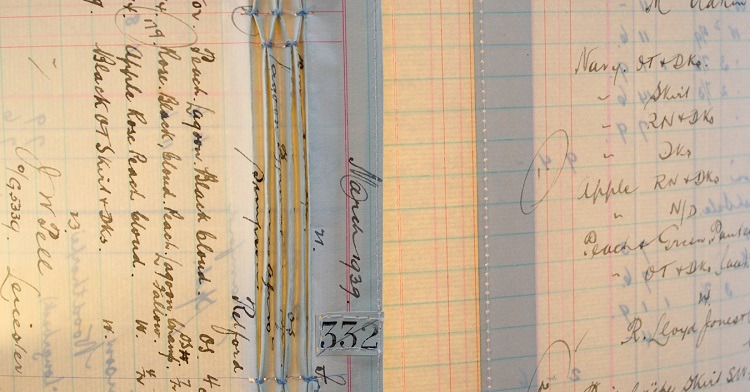

Years back, Fiona experimented incorporating plastic baling straps into her weaving but the results weren’t satisfying. But later, when Covid lockdowns forced her to work with what she had to hand, Fiona again explored ways to weave with the left-over plastic straps. Each attempt was hung next to the other along her studio wall.

One day, Fiona started drawing the hanging weavings, and the idea to create a wall of water came to life. The project would also qualify for submission to the 2021 Cordis Prize for Tapestry that required large-scale works taking an innovative approach to traditional tapestry (she won a spot on the short list).

Using the drawings only as a guide, 15 narrow strips were woven using the traditional Gobelin tapestry technique on a hand-dyed cotton warp, and the weft was mostly cotton and linen in which split baling strapping was inserted. Fiona developed techniques to pull and manipulate the warp and weft, and by leaving warps exposed and unfinished, the tapestry became a 3D woven drawing of the sea.

‘My biggest mistake was trying to make the plastic do what I wanted instead of exploring its unique qualities. Playing with the materials and asking “what if” was the most exciting and fruitful way to construct the plastic weaving.’

Hanging her sculpture posed another challenge. It was important the work had lightness, movement and appeared to float off the wall. So, each strip is hung at the end of a long screw, creating depth and interesting shadows. It also allows the work to be hung in a myriad of ways and ‘recycled’ for different venues.

Although trained as a traditional tapestry weaver, Fiona’s practice has expanded to explore a wider range of materials and techniques. She especially continues to experiment with discarded materials.

‘They all speak their own language and require careful handling. Some I love, while others I find challenging. I hope combining these undervalued materials with traditional techniques will help us reconsider the value of what we use and throw away.’

Fiona Hutchison is based in Edinburgh, Scotland. She has exhibited her work internationally and taught at university level and in-studio workshops. Fiona is a founding member of the European Tapestry Forum and STAR* (Scottish Tapestry Artists Regrouped) and shortlisted for The Cordis Prize for Tapestry (2021).

Artist website: fionahutchison.co.uk

Facebook: facebook.com/tapestrystudio114

Instagram: @fionahutchisontapestry

Wendy Carpenter

Found object designs

There’s something magical about found objects embedded in textile art, especially when they’re surprising elements. Wait, look! That’s rusted metal!

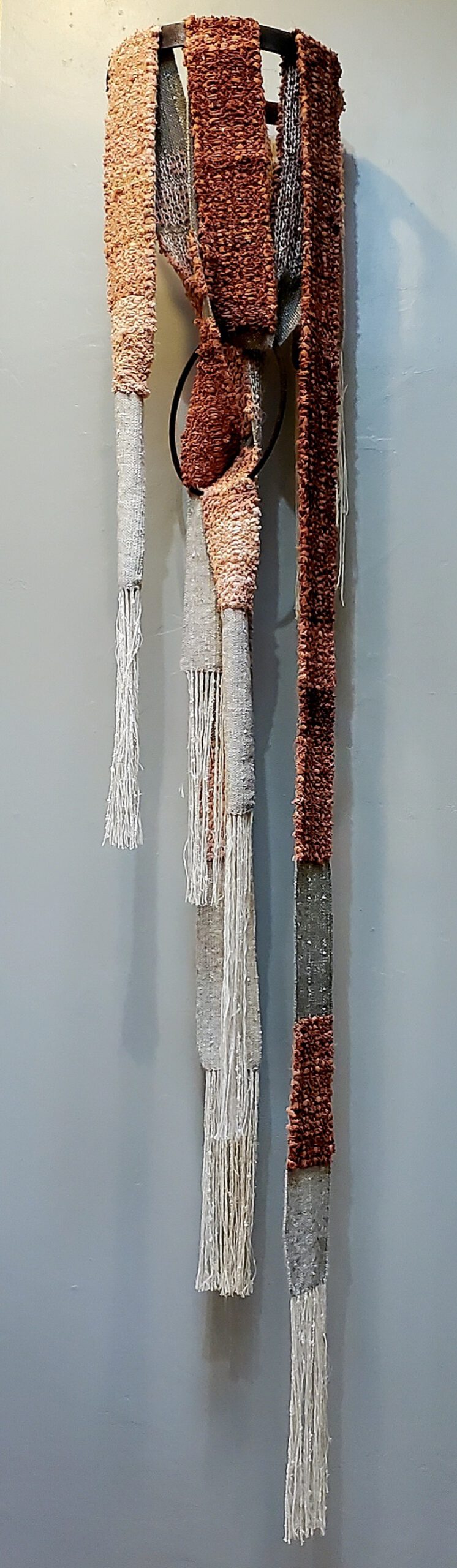

Wendy Carpenter is a master at incorporating random ephemera in her tapestry in ways that seamlessly support her stories. She especially enjoys using natural items, such as a uniquely twisted branch or colourful log. But for this piece, she’s incorporated a rusted tractor piece to illustrate the history of American farming.

‘When I’m out and about, I’m always looking for materials to incorporate into my artwork. The tractor blade was scrap metal found on a farm, and the barrel rims I found on my deck one day. Neighbours and friends know I’m a collector, so they share their random finds.’

The size of Wendy’s works is also remarkable. Most of her woven art towers over her when displayed, and this work is no exception. Wendy says working on a large scale is ‘the nature of the beast’ when it comes to her weaving. Working with sculptural forms and abstract tapestry design necessarily pushes her work into large formats.

Chenille on the Farm features six-inch-wide panels made from a chenille bedspread, which were all handwoven on a floor loom with an inlay threading. Each panel is nearly nine feet long. Wendy dyed the chenille bedspread with a rust pigment to incorporate the fabric with the rusted tractor blade. A lower metal rim repeats the tractor blade material.

‘When introducing found objects from nature or manufacture, it’s necessary to repeat the new design element through colour, form or texture to blend the soft and hard materials. I focus on the overall form, tapestry composition, texture and colour when incorporating repurposed materials.’

Because weaving is a time-consuming medium, Wendy always starts with a sketch for a perspective on the size, proportion, balance and overall design. Although she refers to the sketch for measurements, she will quickly start designing directly on-loom. From there, the artwork takes on its own unique character.Wendy also prefers to work in series. Chenille on the Farm is one of several works in her Preserving Americana series. The collection conceptualises America’s ancestral farming culture during the early 1900s.

‘Working in a series allows me to tell a story through images. Each piece seems to get better as I continue to explore the realm of possibilities to express a visual concept. It also takes time to prepare the weft material and dress the loom, so it’s practical to weave in a series.’

Wendy Carpenter is based in Door County, Wisconsin (US) where she operates her InterFibers gallery. She has exhibited her work at the Miller Art Museum, Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin (US), the Hardy Gallery in Ephraim, Wisconsin (US), and the La Antigua Galleria in Antigua, Guatemala. She has a fine arts degree from Evergreen State College in Washington (US).

Artist website: interfibers.com

Jeni Ross

An abstract approach

Time is the essence when it comes to Jeni Ross’s tapestry work. Her abstract and colourful tapestries showcase the passage of time through shape, form and brilliant use of colour. Her designs incorporate layers, contrasts and cycles to represent movement from day to night, earth to air, and negative to positive moments.

As with all art forms, Jeni’s abstract designs reflect how tapestry subject matter and techniques have changed over time. She agrees with master weaver Archie Brennan that a tapestry can be anything an artist wants it to be. And she points out the fact that tapestries have the advantage of softening a space and absorbing sound in ways that enrich both homes and public buildings.

‘A woven tapestry does have a different aesthetic to a painting, but it can have just as much presence in a gallery and draw an appreciative crowd. I enjoy many forms of tapestry, from 3D objects to a painterly approach that freezes gestural movement forever. But I’m particularly attracted to work that makes a simpler statement in terms of colour, and perhaps, a more hard edge approach.’

Linden Tapestry was commissioned for a London home and woven during lockdown. It’s a wonderful example of how Jeni continues the theme of time and its responses to the landscape.

‘The family loves the Suffolk countryside, so I sought to depict the interconnectedness of the sky, water and land. The client says the red flash in the centre mirrors the exhilaration of stepping out of the sea after a swim.’

Jeni starts her creative process by painting large sheets of watercolour paper with gouache to make a colour field. A sheet of coloured paper is then cut to the proportions of the finished piece as a ground. Additional cut and torn paper shapes are layered and moved about until an initial arrangement begins to work.

When it’s time to weave, Jeni largely uses traditional tapestry weaving techniques. And to help colours stand alone, she uses a kilim carpet weaving approach to create clear shapes with slits between the colours.

‘I love the richness and depth of colour that can be achieved through yarns. So, it’s always important to see how each colour works with or against its neighbour, as well as the overall plan. Sometimes a piece will go in an unexpected direction that may not work as a textile, but I’m always thinking of how an image can work within the constraints of tapestry weaving.’

Jeni Ross is based in Farnham, Surrey, UK. Her work is exhibited across the UK in hospitals, theatres, museums and government buildings. Her largest commission featuring a suite of six tapestries is installed in the Founder’s Library in New College, Oxford. She also created a series of tufted artworks for the Belfast HSS Trust Childrens’ Treatment Centres and Shannon Clinic in Belfast.

Artist website: jeniross.co.uk

Instagram: @iamnotapixel

Molly Elkind

Small, but powerful

The word ‘tapestry’ often evokes images of grandiose wall hangings featuring pastoral scenes or intricate repeated designs. But when master weaver Archie Brennan designed a tabletop copper-pipe loom in the 90s, the weaving world took notice. ‘Weaving small’ became a big thing.

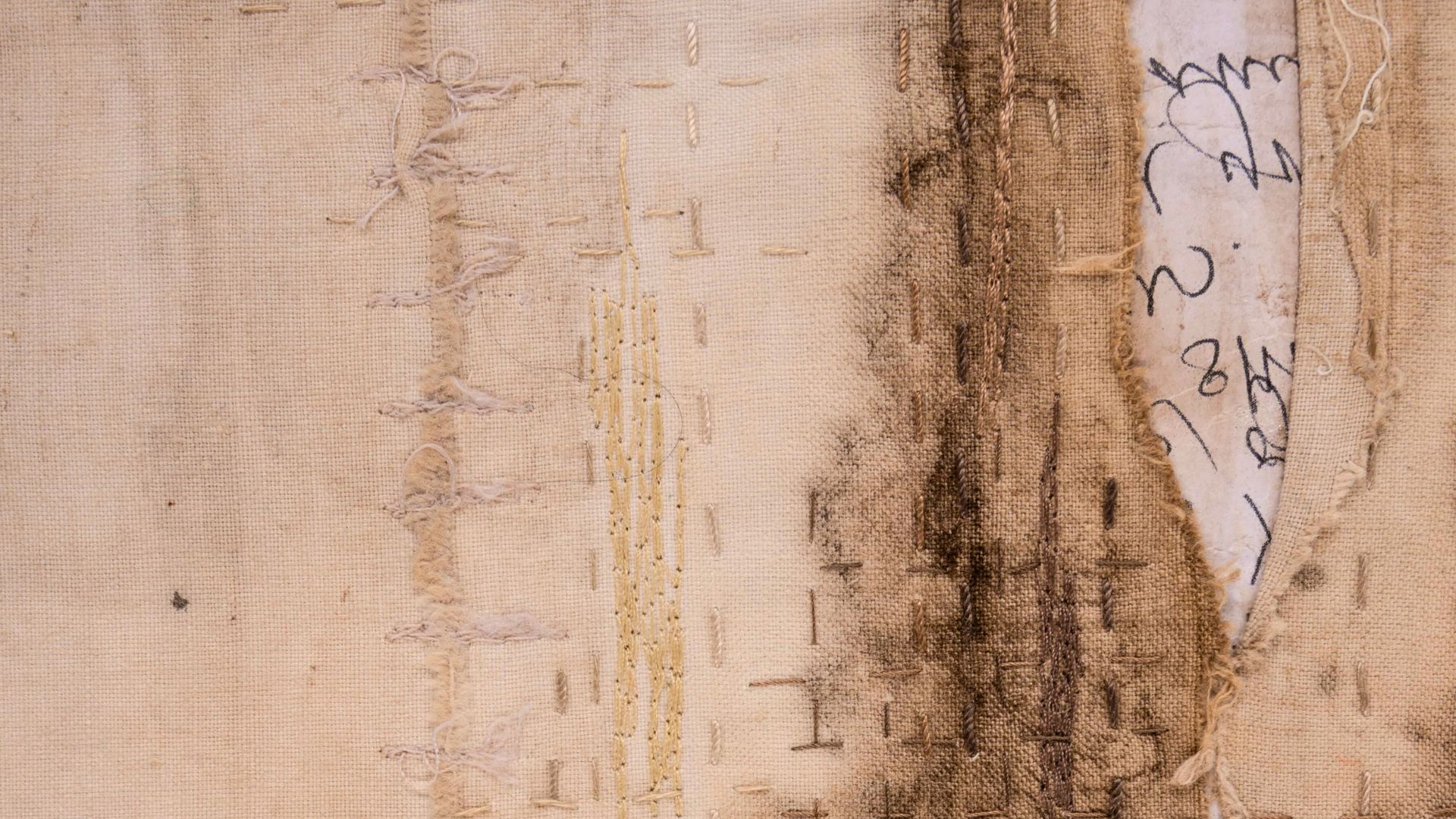

Molly Elkind has been weaving small for the past 13 years, and her petite works have as much impact as any wall-sized tapestry. There’s a research aspect to her small weavings, as she likes seeing quicker results that may inform other works. But Molly also believes small weavings can make grand impressions in their own right because of their smaller imprint.

‘I think of small tapestries as lyrical poems rather than epic narratives. My spontaneous experimental weavings are often looser, freer, and just better than larger, meticulously planned pieces. Small tapestries draw viewers into intimate one-on-one conversations in which the materials and textures can be appreciated upon closer examination.’

Since moving to New Mexico (US), Molly has been enthralled with the high desert environment, and specifically, its beautiful native grasses. Her goal is to move from weaving pictures of local plant life to weaving with the plant life.

Woven Grass Study was Molly’s first experiment weaving with grass. It was woven on a simple frame loom with nails, using three colours of linen for warp and weft. The open balanced weaving technique was inspired by a workshop led by Jennifer Sargent. The grasses are Rhodes grass, side oats grama, Chinese silverbeard and needle-and-thread grass.

‘I treated each stalk of grass as a separate strand of weft, inserting it from one selvedge edge to the other, allowing the top to stick out to one side. I had to take care not to brush the grass with my arm and shatter the seed head as I continued to weave.’

One of Molly’s greatest challenges is preserving grasses in ways that don’t change their appearance. Hair spray, even the ‘extra hold’ variety, didn’t work. Her best success to date is a clear spray enamel, but she continues to research. Molly harvests the grasses as they dry and become brittle in the fields. If further drying is necessary, she hangs grass bundles upside down in a dark garage for a week or two.

‘I have been interested in collage for a long time. I love the effect of juxtaposing different materials to see what sparks fly. It challenges viewers to create their own stories about how the disparate elements relate.’

Molly is based in Santa Fe, New Mexico (US). She has exhibited internationally, including a solo show at Southeast Fiber Arts Alliance (SEFAA) in Chamblee, GA, US (2019) and as a finalist for the Kate Derum Award for Small Tapestries, South Melbourne, Australia (2021). Molly also teaches online and in person with a particular focus on design principles and processes.

Artist website: mollyelkind.com

Facebook: facebook.com/mpelkind

Instagram: @mollyelkind

Comments