Tom Lundberg coordinates graduate and undergraduate programs in fibre media at Colorado State University. He teaches courses in weaving, surface design, and mixed-media textiles.

Lundberg has lectured and taught workshops in the US, England, Ireland, and New Zealand, and teaches in CSU’s Italy study-abroad program.

His embroidered works are in the collections of the Arkansas Art Centre, Little Rock; Indianapolis Museum of Art; Museum of Arts and Design, New York; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; University of Louisville; and Renwick Gallery, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC.

In this interview, Tom takes us on his artistic journey from inspirational visits to his local museum as a child to learning from influential tutors and classmates. We discover how he found his artistic voice which sings out in his dramatic stitched textile art, and why he encourages his students to find their internal compass.

The emotional tones of colour

TextileArtist.org: What initially attracted you to textiles as a medium?

Tom Lundberg: People. As an undergraduate art student, I spent a lot of time painting, drawing, and making pots. In my senior year, I enrolled in a weaving class to spend studio time with friends who were already involved with textiles.

The colour qualities of fabric hooked me: the optical effects of intersecting warp and weft yarns, the cookery of dyes, the lure of making colours from plants.

Batik techniques reminded me of our grandmother’s style of waxing eggs at Easter and dyeing them with onion skins. The emotional tones of colour could change with differences in yarns say, the toughness of linen compared to the warmth of wool.

I liked how weaving required a change of pace in making pictures. Special attention was required for beginnings and endings, and to sequences and rhythms in between.

I paid more attention to handiwork traditions in the family, and to connections with earlier generations in Sweden and Moravia: a great aunt who stitched her poems on linen; men who learned tailoring to bring in more money; the grandfather who listed his occupation as ‘weaver’ on the ship’s manifest when he crossed the Atlantic, even though he would go on to spend most of his life as a farmer.

What or who were your early influences and how has your upbringing influenced your work?

My first memory of stitching is a grade-school craft project for Mothers’ Day, making owl-shaped cases to hold scissors, blue corduroy silhouettes edged with red blanket stitches. When the scissors were inserted into their custom pockets, the handles would make button eyes look bigger.

Your questions have me thinking about that childhood focus on scissors. In the last few years, the subject of cutting has appeared in several embroideries, inspired by the basics of sewing and gardening, and by the depiction of wounds in European vestments. It’s striking, the depictions of pain in such sumptuous garments.

In my home state of Iowa, the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library-Museum is a destination for school outings. The museum has a large collection of flour sacks that were decorated with embroidery in Belgium during World War I, many with flags and emblems of Belgium and the US.

The flour sacks help to tell the story of Hoover’s work with Belgian food relief. Some have printed designs of American mills; others are edged with ribbons and lace. Even as children, we understood that these humble objects had become special with stitching, communicating with a language that connected people on separate continents.

My friends and I also watched as women in our small church sewed a set of altar hangings for holidays and the ecclesiastical seasons. During weeks of project planning, the sewing team, including our mother, browsed sales catalogues that showed clergy wearing robes and stoles. The pages illustrated fancy fabrics and an assortment of machine-embroidered emblems.

At age ten, I was intrigued by the production and consecration of these ritual items, and with the symbols stitched onto fields of red, green, purple, and white. And there was a bonus: the storage chest that our father helped to build was placed into a dark space at the base of the belfry, accessed through small doors.

The grownups seemed to not notice that we could see the bottom of a ladder leading up into the tower. This was certainly off-limits, but when the opportunity presented itself, we climbed the ladder and found an exhilarating secret view of the town.

The gift of art

What was your route to becoming an artist?

Making things from imagination was routine in childhood: pictures and projects in school, party decorations, parade floats, and forts made with branches and twine.

In high school, I worked as a photographer for the local newspaper and spent a few years framing and cropping images. At university, I took art classes every term but didn’t land on art as a major right away.

At age twenty I spent a summer as an apprentice to Clary Illian, an Iowa potter who had worked with Bernard Leach at St. Ives in Cornwall. I continued to make pots in school after that but could see that I was more of a picture-maker.

At the University of Iowa in the mid-1970s, I studied art with very good teachers. Our weaving professor, Naomi Kark Schedl, was from South Africa, where she had trained as a painter.

My classmate Barbara Eckhardt was way ahead of me in textile thinking. She worked with complex weave structures and was deep into books about historic textiles and tapestries. Her love of borders, patterns, and visual compartments was contagious.

While she wove birds inspired by Coptic medallions, I copied hippie embroidery on work shirts and stitched a few pictures, too. These were gifts and seemed to have little to do with art classes.

Naomi guided me to several possible graduate programs, including Indiana University. There, with patient encouragement from teachers Budd Stalnaker and Joan Sterrenburg, I floundered through an assortment of techniques and eventually began to stitch on batiks, and into weavings and patchwork paintings.

Tell us a bit about your chosen techniques. How do you use these techniques?

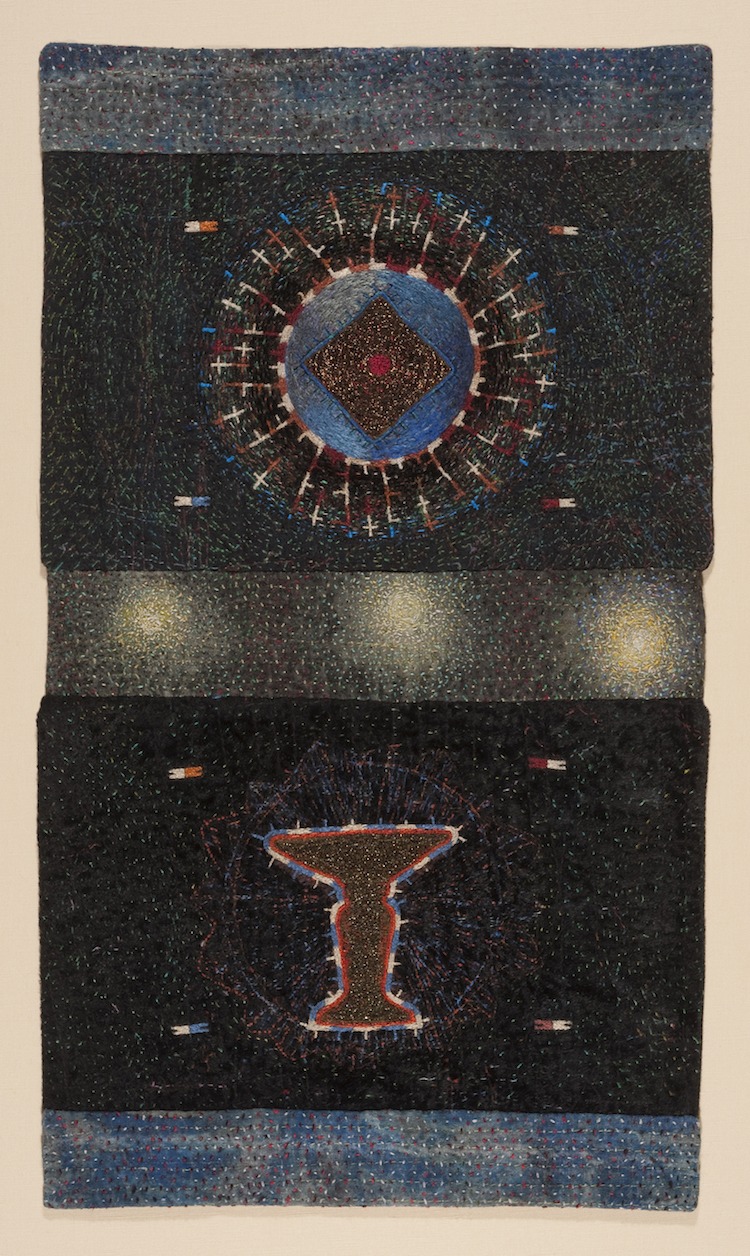

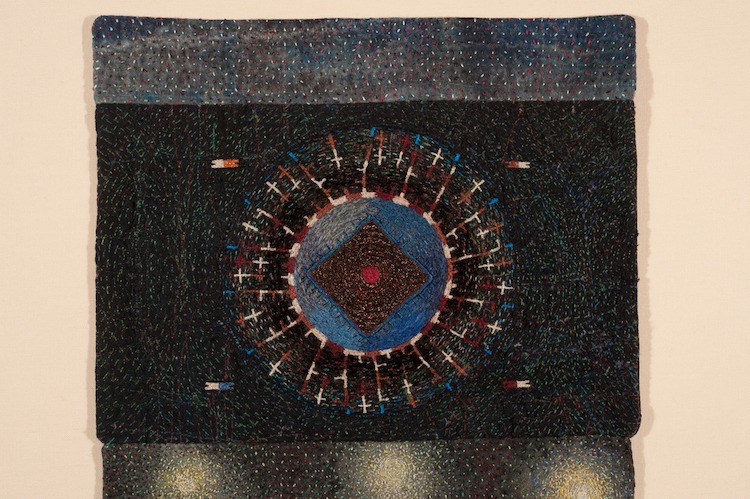

It was easy to become absorbed in weaving tapestries, but a research assignment led me to look more closely at embroideries of the Middle Ages and Renaissance.

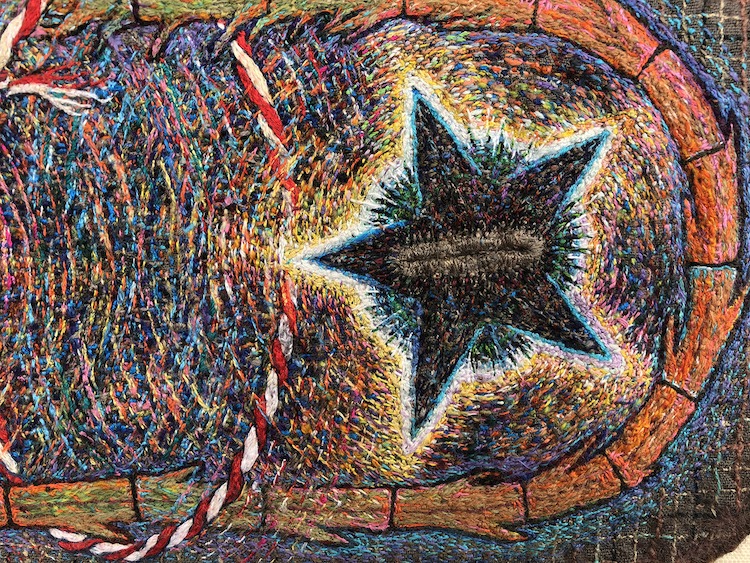

Classmates and I visited the textile collection of the Indianapolis Museum of Art, which includes a few European vestments with embroidered orphrey panels. I clicked with a few basic techniques: long-and-short stitch, split stitch, and couching.

Compared to the methodical buildup of yarns in tapestry weaving, these stitched textures allowed colours to blend in any direction.

A glimpse of everyday life

How would you describe your work and where do you think it fits within the sphere of contemporary art?

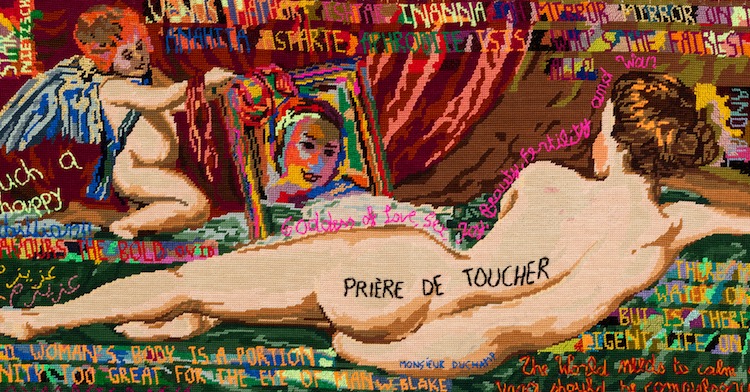

When I began to embroider in the 1970s, teachers pointed me to the works of Alberto Burri, whose wartime experiences and training in medicine can be felt in his stitching of rough, worn fabrics. The few artists I knew who worked with stitching had trained in textile media. Today, it’s easy to find artists from any discipline using stitch and thread.

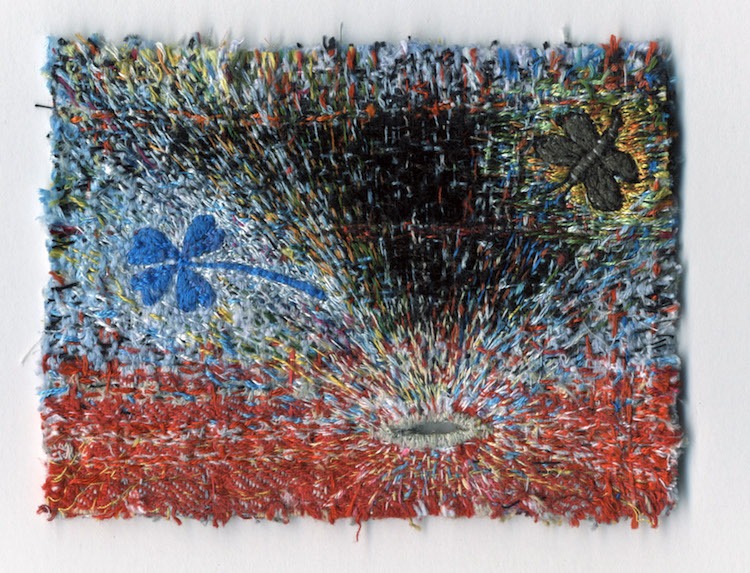

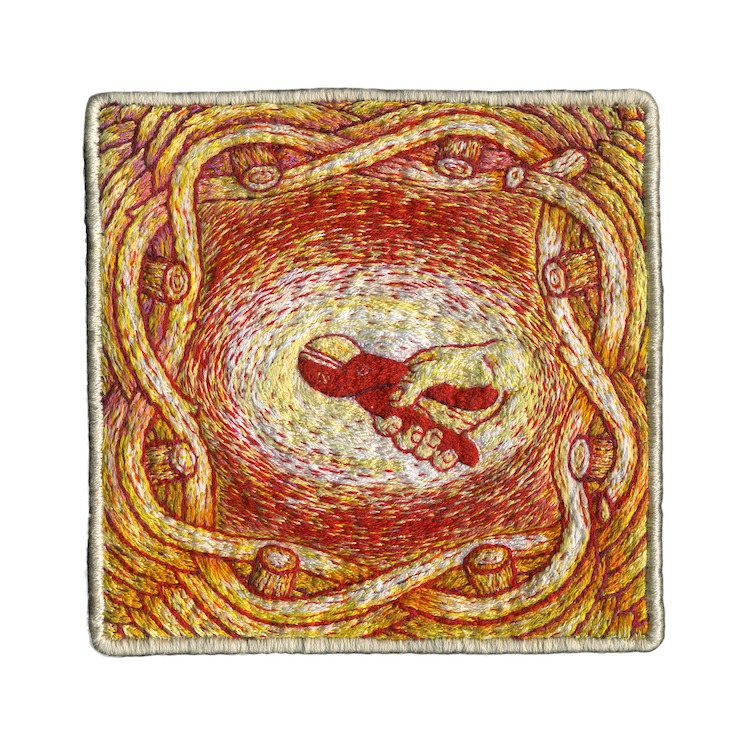

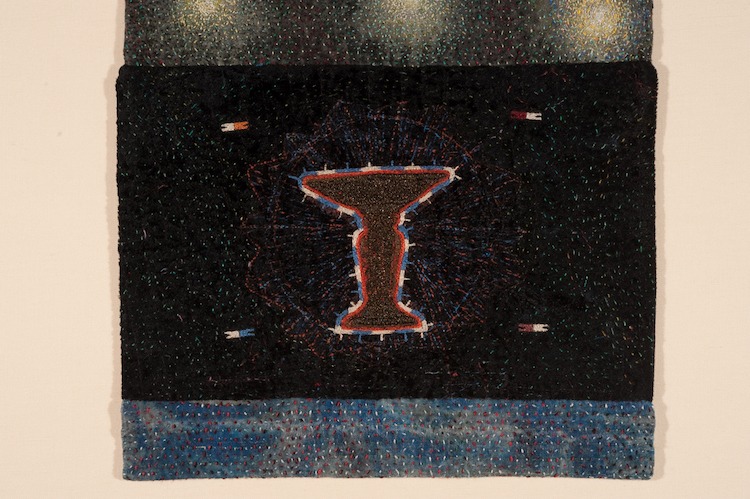

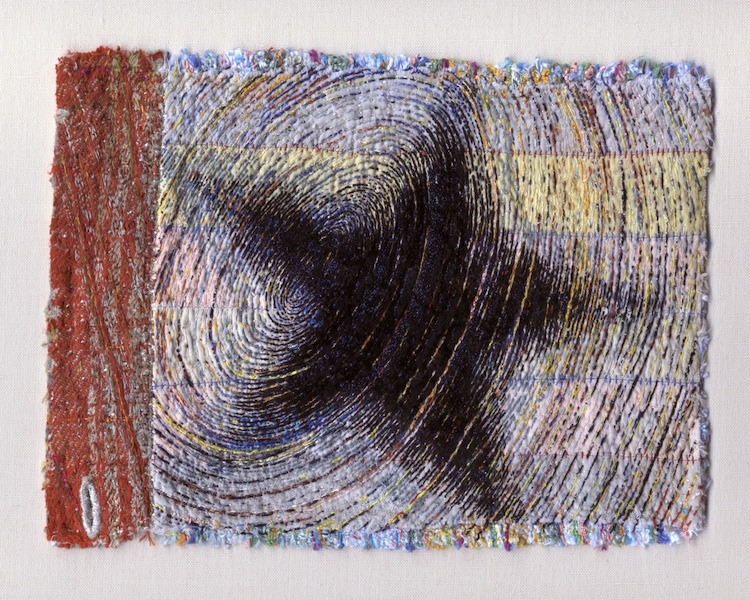

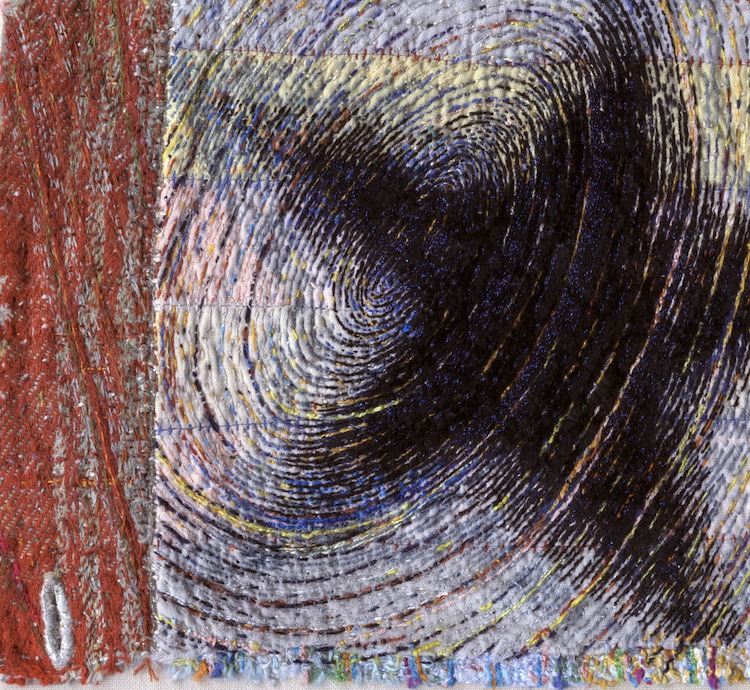

My own embroidered pictures contain fragments of memory and glimpses of everyday life. These small textiles often take the form of swatches, badges, and cuffs. Shapes that follow the movements of people.

Tell us about your process. Do you use a sketchbook? What preparatory work do you do?

I sketch in coloured pencil when I want to plan an embroidery. I also make simple collages of photos and photocopies.

Sometimes, I just start by stitching around a cutout shape and seeing where that takes me. In the last few years, I’ve made small panel paintings that offer starting points for future textiles.

I keep portfolios with clippings, photos, and photocopies of shapes and images. They’re organised by such categories as Earth, Air, Water, Fire, Gardens, Geometry. I have enough photos to inspire a thousand works, but can’t stop trying to capture random moments and details.

I audition shapes and formats by moving around paper cutouts and pinning them to fabric on the wall. Sometimes I play with rhythms of patterned fabrics to consider proportions or layout. Colour decisions often evolve as I work, but I tend to establish light-and-dark value structures at an early stage.

The edges of the forms are important. Whether bound with stitches or cut to suggest a raw-edged swatch, I want the sides to have a textile quality.

What environment do you like to work in?

I like to work at home in my basement studio. For small pieces, it’s easy to pack my sewing kit into a small bag for working almost anywhere else. If the light is OK, I can stitch in a car or an airport.

A shared approach to textiles

What currently inspires you?

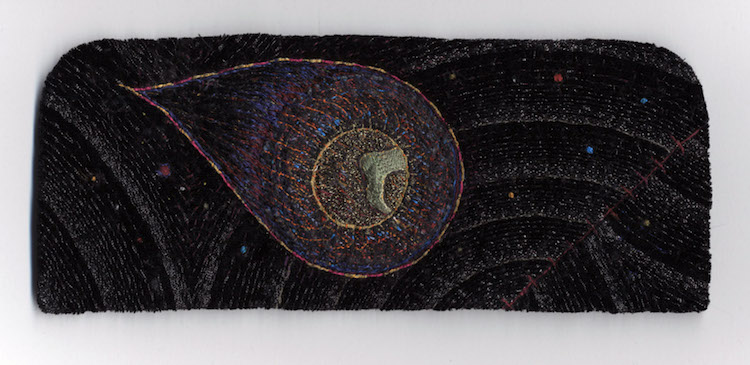

The oval shape of Short Strap for a Long Winter was inspired by a detail in Attention, Company!, a painting by Willam M. Harnett (1848–1892) at the Amon Carter Museum of Art, Fort Worth, Texas.

The painting depicts a boy dressed as a make-believe soldier. He wears a tattered coat closed below the collar with an oval tab and two buttons.

Who have been your major influences and why?

In addition to the people that I’ve mentioned, Diane Itter and William Itter were important mentors when I lived in Indiana. Diane’s linen knotted works and Bill’s paintings are alive with colour and complex spaces.

Their collections of folk art and textiles left a big impression, too. Diane’s classmate Renie Breskin Adams and my own classmate Anne McKenzie Nickolson helped to shape my approach to textiles.

My colleague Richard DeVore also helped me to understand how craft media embody fundamental human conditions. His clay vessels give form to pain, sustenance, and the will to survive.

Tell us about a piece of your work that holds particularly fond memories and why?

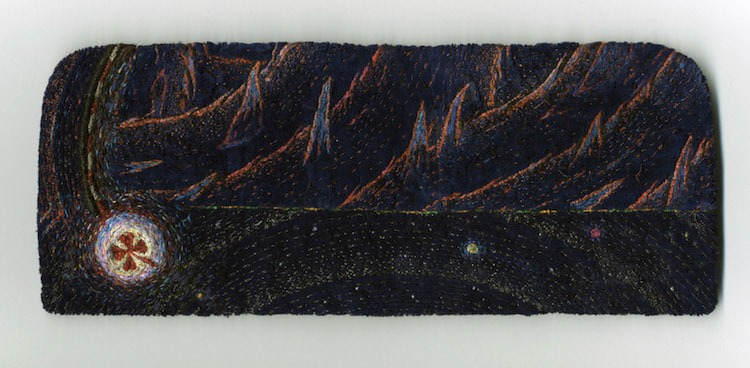

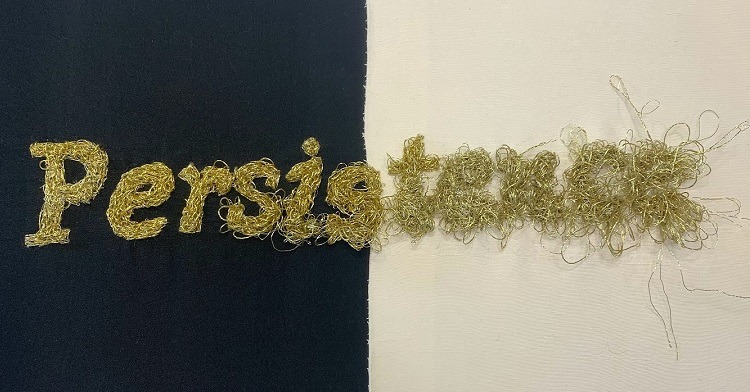

The jagged shapes outlined in Narrow Escape are taken from borderlines in my grandparents’ 1931 atlas of the world.

On winter afternoons, we sometimes would have geography lessons on the family homelands. Not all the memories were happy ones for our grandparents. The atlas triggered their stories about captured territories and hurried wartime departures.

Narrow Escape is a kind of fictionalised depiction of those stories. The scrap of fabric near the centre is inspired by the stripes of a bag that our grandfather carried to the US.

What advice would you give to an aspiring textile artist?

I encourage students to not be afraid to try things and to be receptive. To look to the nature of textiles for guidance. To trust their instincts and to find an internal compass.

Can you recommend 3 or 4 books for textile artists?

[easyazon_link identifier=”0500203431″ locale=”UK” tag=”wwwtextileart-21″]The Language of Ornament by James Trilling.

[easyazon_link identifier=”B00DJG3P36″ locale=”UK” tag=”wwwtextileart-21″]The Poetics of Space by Gaston Bachelard.

Currently, I’m reading a book recommended by a colleague: [easyazon_link identifier=”B01EAHZHAG” locale=”UK” tag=”wwwtextileart-21″]Lines: A Brief History by Tim Ingold.

What piece of equipment or tool could you not live without?

The basics: plastic embroidery hoops, needles, and little scissors.

Do you give talks or run workshops or classes? If so where can readers find information about these?

In addition to teaching at Colorado State University, I occasionally lecture and teach workshops in other places. In early August 2018, I will teach a five-day workshop at Textile Centre in Minneapolis.

Where can readers see your work this year?

The Textile Centre in Minneapolis will feature my work in Summer 2018. And in July–August 2018, I’ll exhibit with friends at Artworks Loveland in Colorado.

For more information visit: www.tomlundberg.com

If you’ve enjoyed this interview why not share it with your friends on Facebook using the button below?

Comments