In her youth, Merill Comeau resisted gendered expectations and manifested her quirks through fashion. She embellished garments and often wore men’s clothes.

Today, she continues to use stitched textiles to assert her beliefs. Through her art she reflects her innate interest in societal hierarchies and material culture while expressing her feminist principles and rebellious nature.

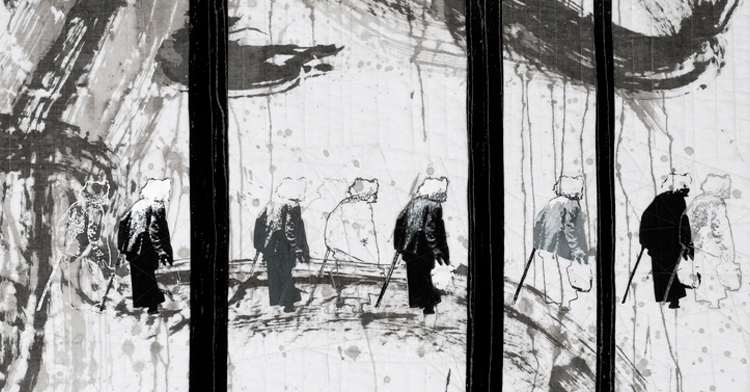

Merill’s installations and large wall hangings often examine the narratives of deconstruction, repair and regeneration. Layers of fabric embellished with paint, dye, stitch and text explore common human concerns, like mending and endurance, and both historical and contemporary women’s roles.

By using repurposed materials Merill throws the spotlight on environmental sustainability. But her strong attraction to worn textiles is also linked to the hidden histories they hold and the importance of textiles in our lives. Each unpicked garment or fragment of domestic linen contains the touch of all those who created and used it. Through the collaging and piecing of these soft and tactile materials, discover how Merill tells meaningful stories and makes connections with the past.

Essential textiles

What is it about textiles that makes you want to work with them?

Merill Comeau: Textiles evidence our cultures, socioeconomics, and challenges of global sustainability. They are an essential element of our daily lives: we are swaddled when born, we sleep in linens, we clothe our bodies, and we mark life’s passages with ritual garments and fabrics.

“Working with textiles provides a concrete and sensual engagement with the material world.”

I like being surrounded by inspirational textiles. Aged fifteen, I purchased a decrepit, antique Chinese embroidery made of blue silk threads on deep red wool, which I meticulously restored. I continue to collect fabrics such as 1950s abstract bark cloth, samples of crewel on linen, crazy quilts, contemporary Dutch wax African fabrics and geometric woven rugs.

To convey narratives of mending and endurance, I employ worn fabrics of the domestic sphere and the mark making of stitch. Ninety percent of my materials are repurposed – my mother-in-law’s blouse, a stained tablecloth, discontinued designer prints – each textile communicates identity, reveals lives lived and embodies memory.

I enjoy the working processes of textiles. I make marks using dye, stitched resist or block printing, followed by construction, fabric manipulation, seaming and repair. Further decoration is achieved through embroidery, appliqué and embellishment. I compost, paint, print and rust my source fabrics, transforming them into my own visual language by creating a new, varied surface.

When I stitch using needle and thread – a repetitive, meditative act – I am connected to thousands of years of textile traditions and to a contemporary community of makers telling stories of our complex world.

Are there particular topics or themes that inspire your work?

My landscape work is inspired by nature and observing the change of seasons in New England. Plantlife is an apt metaphor for our lifecycle: plants sprout, bloom, wilt, and return to the earth to bloom again. For me, portraying the profuse vegetation of local trails and gardens symbolises a complex world where we are bombarded with information.

I use the formal elements of landscape painting as a structure to help me puzzle through and arrange hundreds of disparate snippets into a unified scene. I keep my focus close to the ground, as in a worm’s eye view, representing our relationship to the power of our environment.

My abstract work is informed by trauma, mending and healing. I am inspired by resilience. At times, words and pictures fail to express narratives of confronting challenges, surviving difficulties and emerging in a new, stronger self. Colourful fabrics and stitched marks give a visual voice to human experience – including the joy of thriving.

I draw on what has come before by researching and viewing historical textiles. I see continuity across centuries of change at the same time as I anticipate continued rapid change in modern life.

“Applying traditional techniques in new ways and abstracting traditional decorative motifs gives me a visual vocabulary to take part in a long process of women telling stories about their lives.”

How do you develop ideas and plan your work?

Research is integral to my creative process. I prioritise time to read books and do online research to broaden my knowledge and understand a variety of topics and art. Much of my learning about ideas, history and current events is accessed through the written word. I consider it my job to translate these words through my personal lens into visual communication.

There are times when words fail to capture and express the human experience. Art fulfils the impulse to document our existence and stimulates connecting conversations about the world around us.

In terms of planning, I don’t use sketchbooks to draw an imagined finished work, or for creating drawn instructions to follow, but I do keep several sketchbooks for a variety of purposes. For example, one is filled with images that inspire the abstract printing blocks I use to create my own patterned fabrics.

Another is full of inspirational photos of nature, to assist me when I’m creating work using nature as a symbol of our life cycle. I have an ‘ideas’ sketchbook for self-reflective writing, brainstorming notes, title ideas and phrases I want to remember.

“Using sketchbooks helps me keep track of thoughts and flesh out ideas. Their content enhances my design process and helps me develop the conceptual underpinnings of my work.”

An example is Archive of Specimens, an ongoing contemplation on absence and presence. I’m a collector of tidbits of nature, representing places and people I’ve visited, as well as my wonder at the natural world. On my studio shelves are seed pods, nuts, berries, feathers and rocks: items intrinsically holding memory, meaning and beauty. My ‘souvenirs’ of flora and fauna mark a moment in my, and their, existence.

I rendered these elements in pencil on paper, then translated the drawn image with thread onto painted fabric. I cut out these meditations and layered them on backgrounds not their own, for example, a pine cone illustration stitched to a background with a cut-out hole that was once the shape of a shell. The tiers of mismatched solids, voids and shadows express the mysteries of life and my sadness at impending loss. Research about the current challenges of managing natural history museum collections and the Victorian practice of collecting specimens from nature influenced this documentation of my own collection.

An emotional dialogue

Tell us some more about your process, from conception to conclusion.

I tend to work in series, although I don’t always know in advance what the link will be between works. The conceptual underpinning becomes evident over time, and then I build upon the discovered and identified theme. Looking back, I can see I’ve often worked in three-year blocks.

My first source of inspiration is usually autobiographical, the next sphere of influence comes from my surrounding community of family, friends and students, followed by my awareness and understanding of issues and experiences that bind us as human beings.

At the start of every series, I find I have something I need to say or an issue to puzzle through. This results in an emotional dialogue with the world, created through visual means.

In the midst of a series, I continue to write, and sometimes draw and paint, to flesh out and illustrate components of history and narrative. Phrases from my writing may be incorporated into the work through titles, stencils or stitches. Drawing, painting and textile work happens in tandem.

An example is Fond Memories of Good Company, created in response to the isolation of the pandemic. Snippets of textiles saved from my dining room and kitchen evidenced a previous life of cooking and eating with others. As I drew on memory and articulated my longings, I rendered kitchen implements and tableware surrounded by stitched check marks, referencing past shared meals.

After researching Boston’s history of women painting on china, once one of the only respectable sources of income for women, I studied the china handed down from my relatives. Large stencils of their patterns help me to express connections between women who came before and how I live today.

Could you explain why you are drawn to making large scale works and installations, and how you approach large works?

One of the interesting things about postmodern art is the way the works come off the wall and engage all the surfaces of spaces. This changes the viewers’ experience – they are enveloped and/or encased in art that is larger than their bodies.

In my installations, I refer to domestic spaces, and large collections of elements are gathered into spaces the size of a residential room. I also make large wall hangings that stand alone. This is the scale with which I am most comfortable.

I like the way that making these artworks requires me to use my whole body. The result expresses our experience of the power of our surroundings.

It is important for artists to identify the scale at which they are most comfortable. To experiment, I suggest starting small and increasing the dimensions in successive efforts, learning new construction methods with increasing magnitude. One approach I use is to create a collection of smaller components, which are combined into one large final work.

What or who were your early influences, and how has your upbringing influenced your work?

My grandmother and mother sewed clothes. I grew up occasionally using a home sewing machine and picked up skills in a traditional home economics class. But I also fought hard against my family’s gendered beliefs, like girls needed to learn to cook – the kitchen felt like a traditional restrictive woman’s sphere, and I didn’t want to be there.

I rebelled against expectations, finding expression through sewing and fashion. I wore men’s clothes and altered garments to express my quirks. I bought vintage clothes and personalised contemporary pieces with paint and embroidery.

I sought out influences aligned with my feminist beliefs. I saw the feminist work The Dinner Party by Judy Chicago when it first toured the US, and the idea of taking back traditional women’s crafts and using them to tell stories in a new way inspired me. The table settings honouring women in history really spoke to me. It was a revolutionary and radical domestic reference.

Learning about Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro’s Womanhouse project opened my eyes to the possibility of a woman’s sphere that encouraged questions, evaluation, and the critique of norms.

My degree is in social theory and political economy, and I’m interested in the ways we organise human society and what our material culture communicates about our values.

“Textile history and feminist theory are a rich source for learning, reflection and inspiration.”

In my strong palette, all-over imagery, and hanging of loose fabric on the wall, I owe a debt to the Pattern and Decoration Movement. In my use of recycled clothing and sewing construction, I pay homage to the history of women patching together salvaged bits of cloth to make quilts. My conceptual base continues to express my feminism and evaluative nature.

Woman Interrupted

Tell us about a favourite artwork…

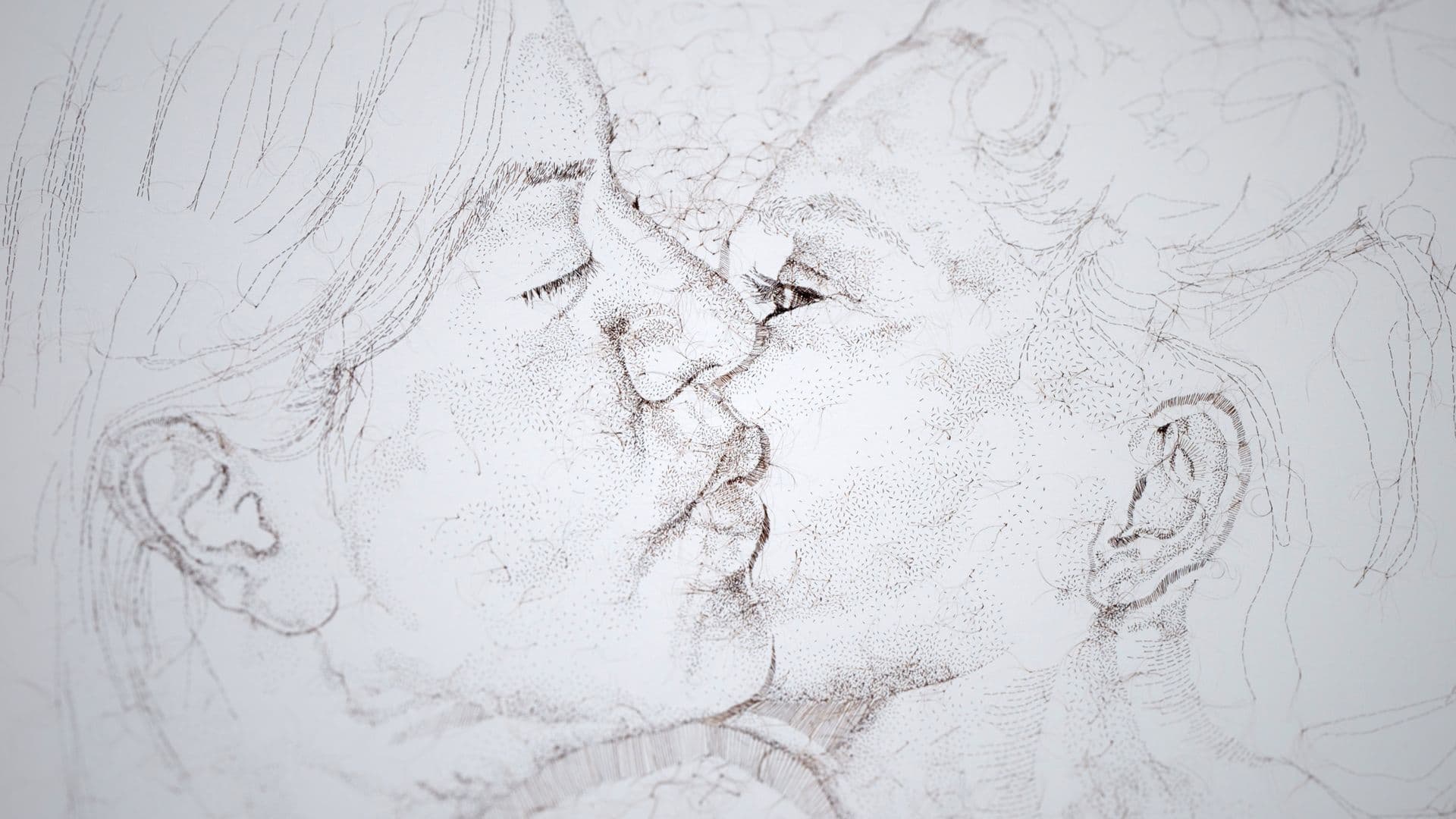

As most of my materials are donated, I often find another person’s stitches on linens and garments. In my stash I found a donated tablecloth with printed crewelwork design lines. An unknown previous owner had begun embroidering with beige wool on beige linen but must have been interrupted as the project was abandoned.

I researched the Asian, European and American influences that developed crewelwork decorative preferences and designs. I decided to ‘complete’ the project by embroidering large colourful stitches surrounding the incomplete elements. Colour choices and stitch style reflect my contemporary tastes.

An inherited piece of family crewel embroidery provided additional inspiration. I created stencils inspired by its design of pomegranates and flowers. These simplified and abstracted inked elements, related to my history, populate the open areas of the cloth. The work is titled Woman Interrupted. While making it, I felt connected to women known and unknown, to varied domestic spheres, and felt that I was bringing history into modernity.

Would you share a little about your community projects?

In addition to my solo studio practice, I work with community groups, young adults and college students to create collaborative works of art. I’m committed to the use of visual expression as a way of telling stories, transmitting knowledge and teaching values. I offer workshops exploring individual identity and shared group missions.

Often groups wish to develop further and express their purpose to a wider world. I lead participants through a series of activities exploring their unique characteristics and opinions. Following exercises helps the group to identify what they have in common. These art projects provide opportunities for participants to work out ideas and translate what they have learned into visual representations.

Past projects have included working with young people to make collaborative wall hangings expressing their experiences in the Massachusetts court system while residing in treatment residences. And I regularly work with multi-generational spiritual communities to create fabric collages that explore and express family life and values.

In 2020, the Art Lab at Boston’s Institute of Art hosted my participatory project Threads of Connection, in which visitors created symbolic self-portraits to explore the diversity of museum visitors. In addition to helping people grow and learn, the impact of my students’ experiences and my observations of the wider human family provide me with rich inspiration.

Comments