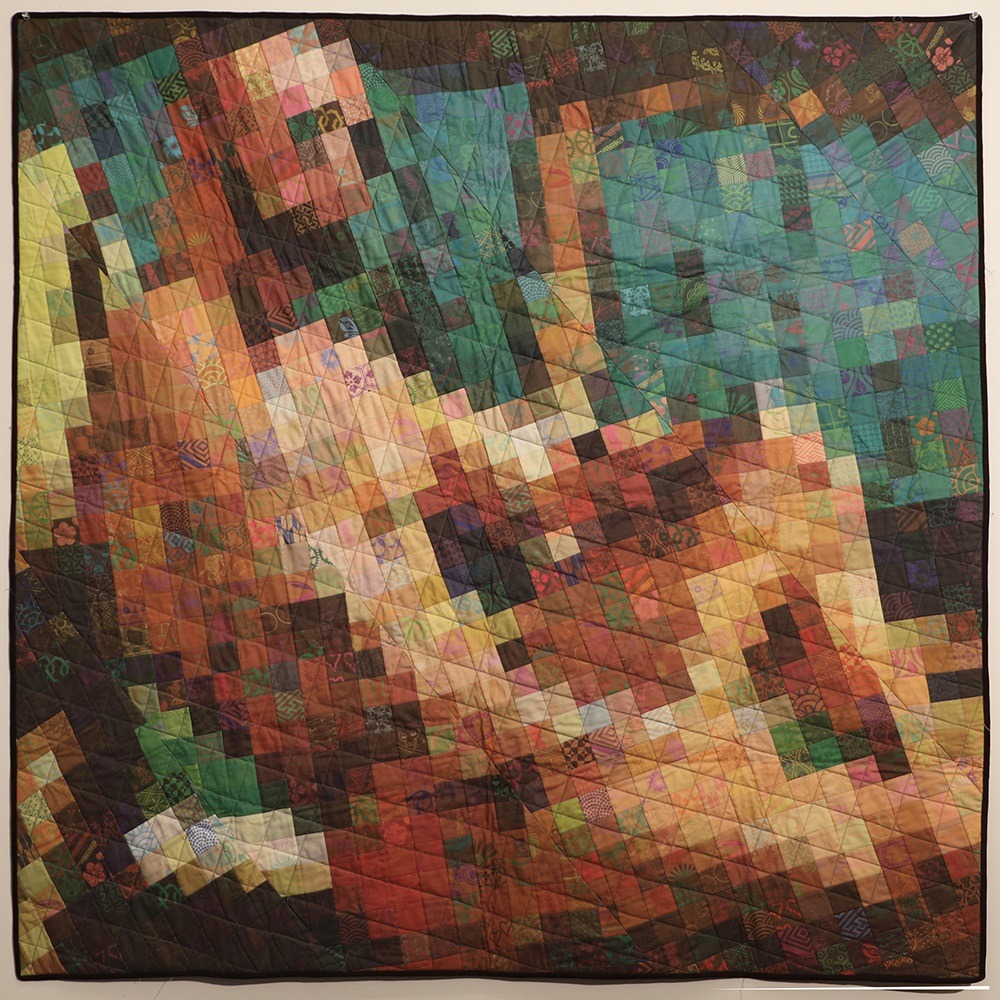

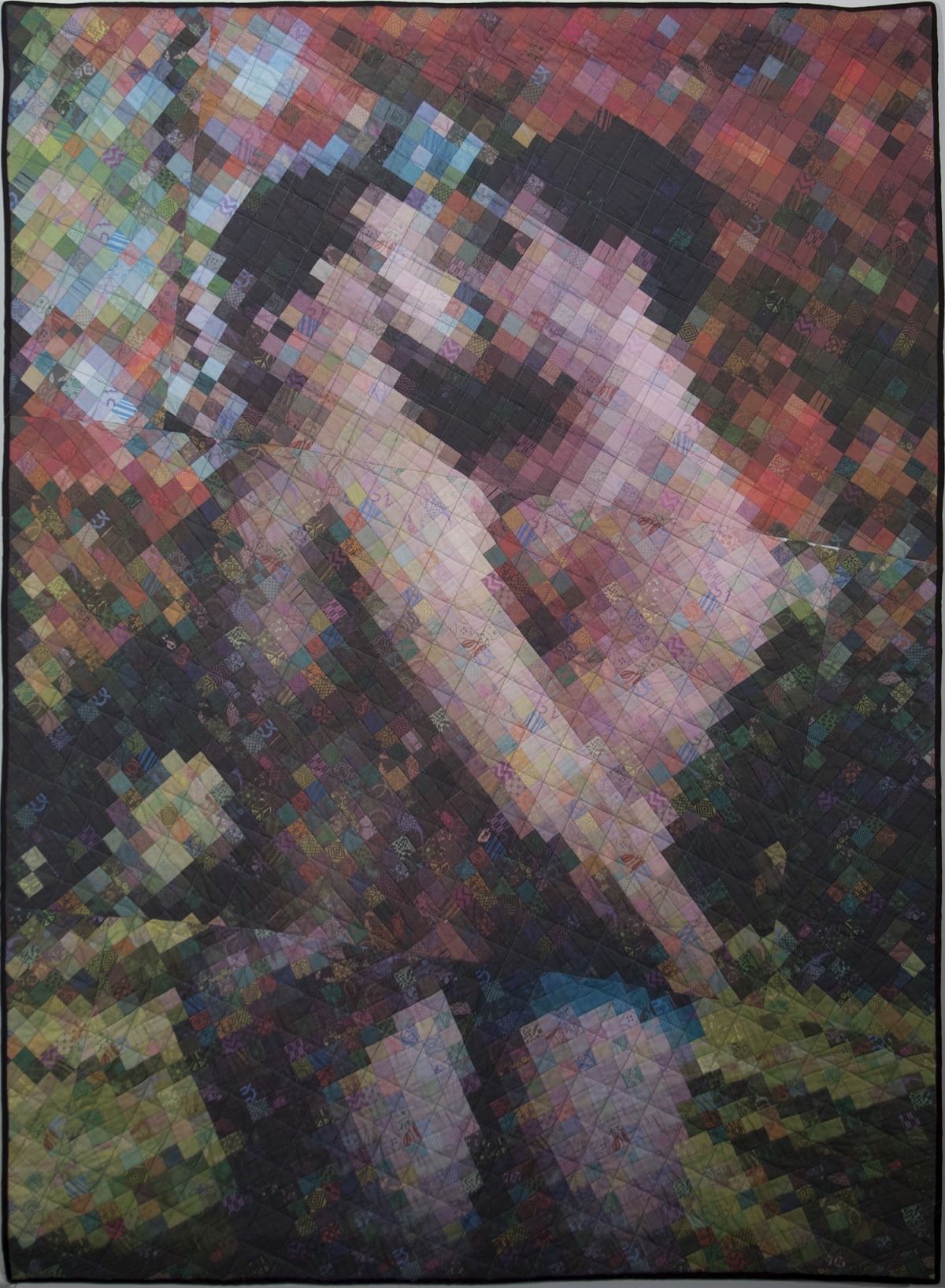

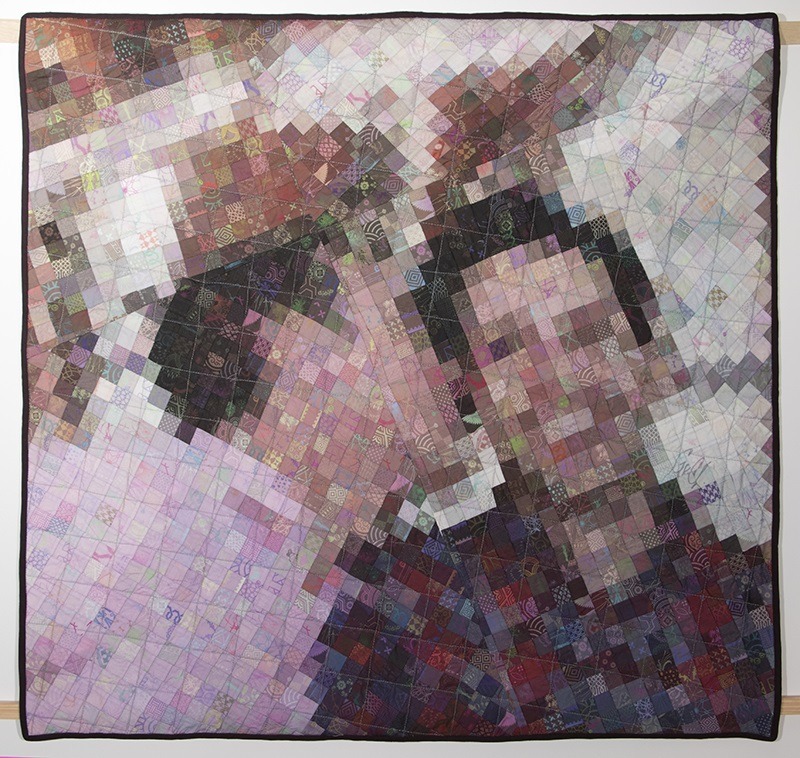

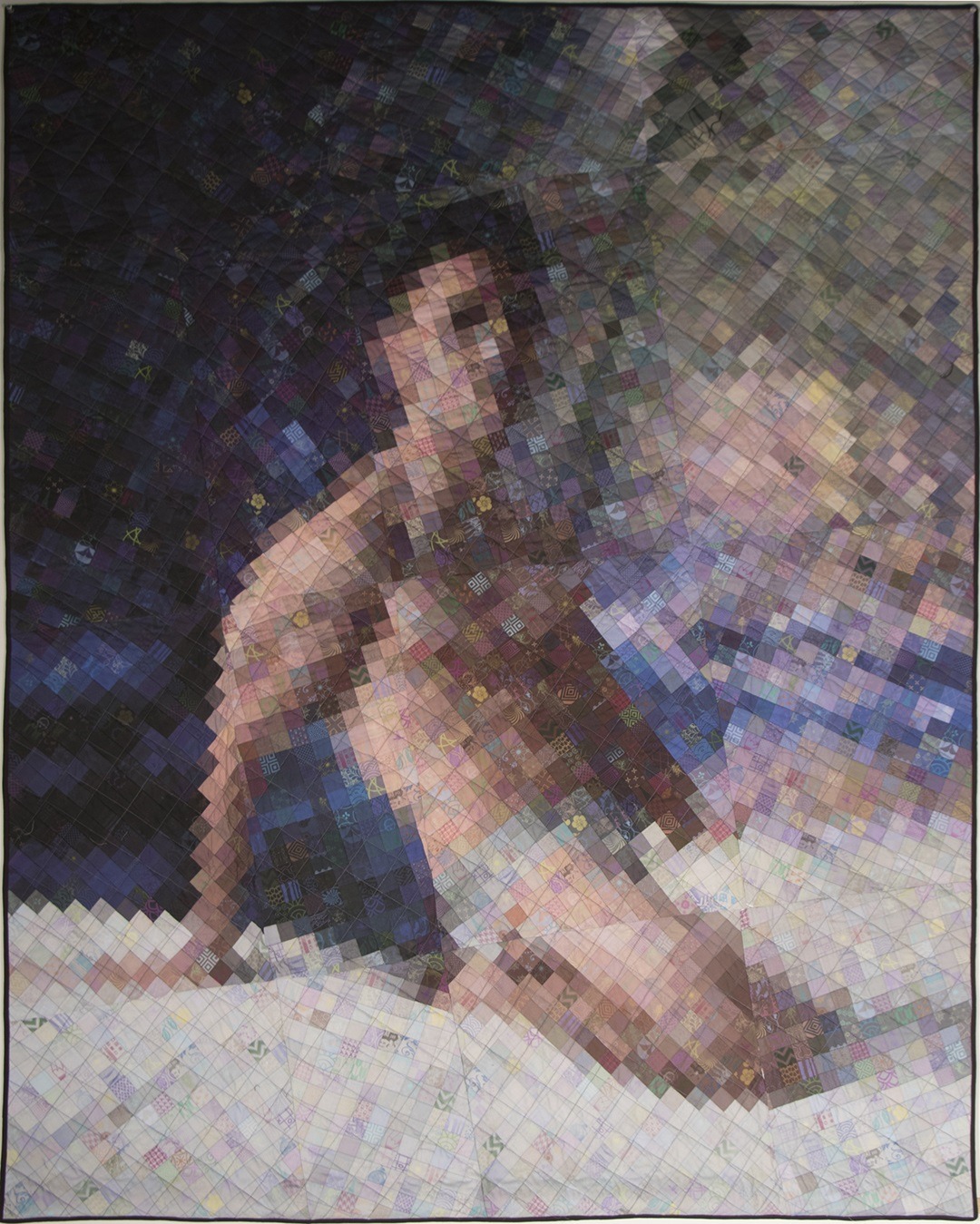

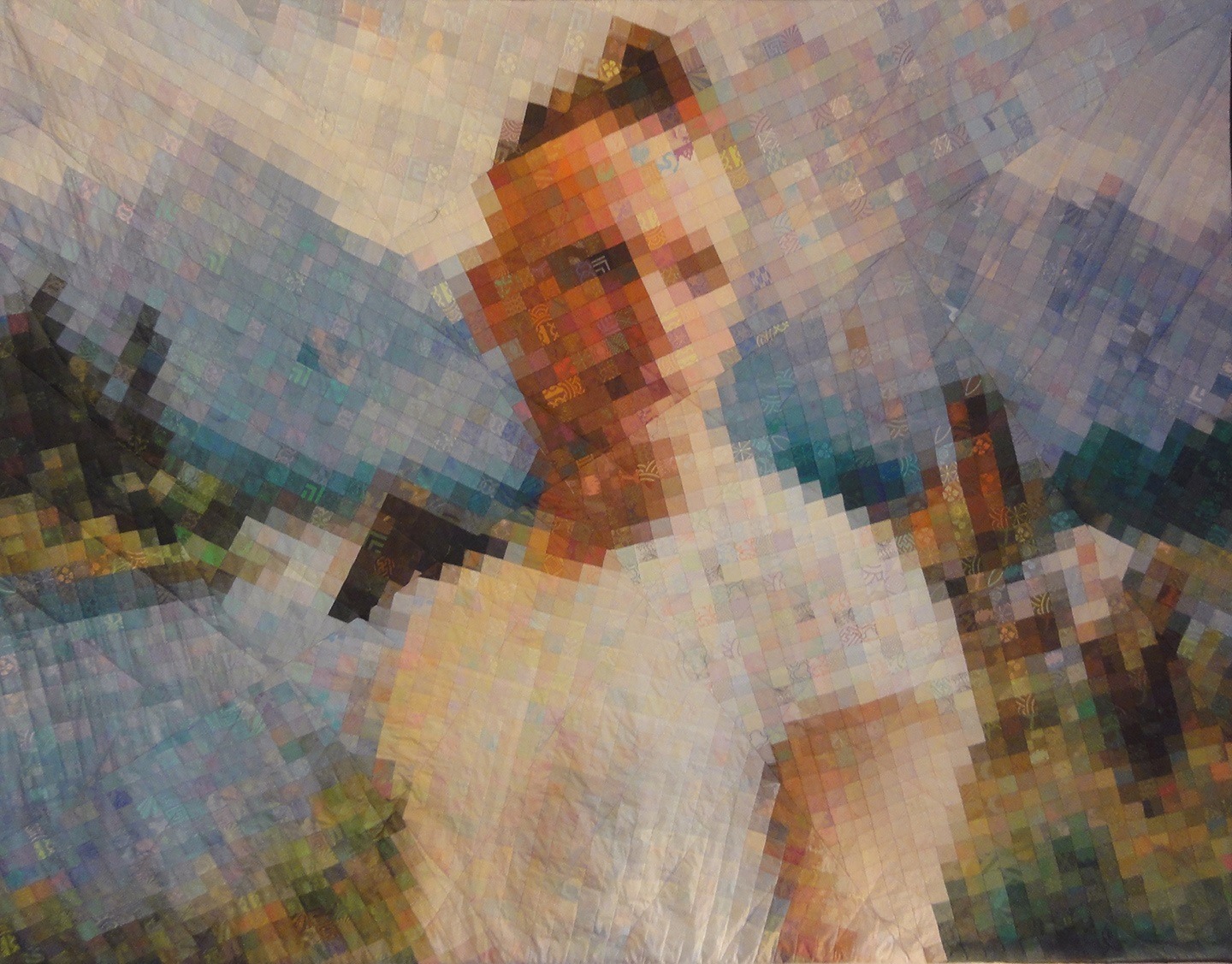

Greg Climer’s pixelated quilts are captivating, colourful portraits enabled through the use of technology, which he uses to augment a traditional craft into something truly modern and exciting.

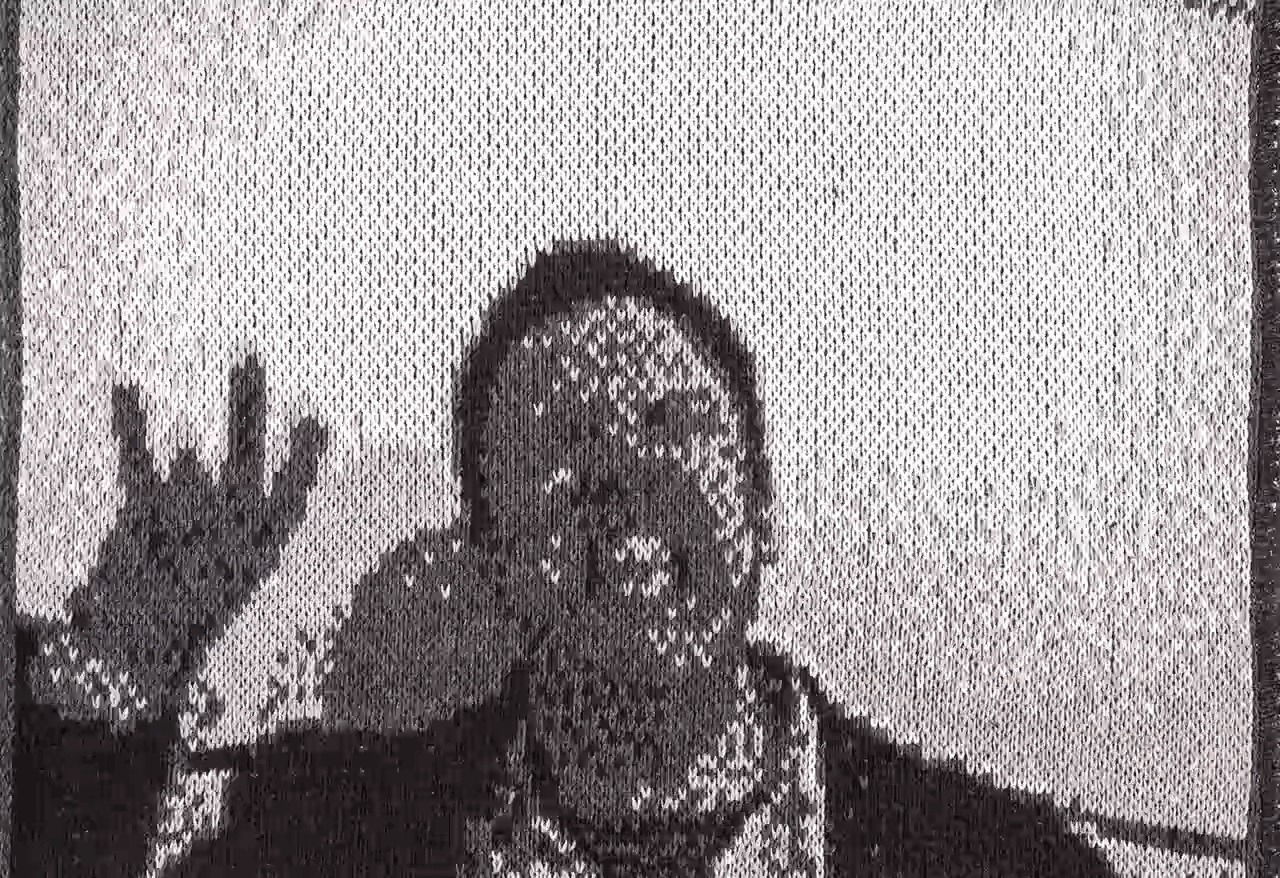

His quilts are designed by taking photographic images or collages and converting them into a pixelated form, blurring the image without obscuring it. The pixel images are then digitally printed onto cotton, ready for construction into a quilt using traditional techniques. Alongside working on his quilts he creates ‘knitted films’ through the painstakingly slow process of recreating reels of film in knitted form, frame by frame, which he then re-animates into video format.

Greg holds a BA in theatre design and classical studies and an MFA in Design Technology. He started off as a pattern maker for costume design in theatre, then moved into the fashion industry. Currently, as a practising artist, he mixes his signature style of quilting and knitting with the use of technology. Greg is also an Assistant Professor at the Parsons School of Design, New York and was artist in residence at Museum of Art and Design, New York in 2016. His work has been shown in galleries around the US and is in the permanent collection of the Leslie Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art.

In this interview Greg shares how his career developed from learning to sew as a child. He talks about his promotion of equality and gay rights through his work. Find out how he’s driven by his love of innovation, to use high-tech approaches within a traditional craft. He explains in detail how he constructs his playful quilt portraits and shares his advice on how to push your boundaries by using ideas from outside of your field to become more experimental with your processes.

Textiles need to be touched

TextileArtist.org: What initially attracted you to textiles as a medium? How was your imagination captured?

Greg Climer: My grandmother taught me when I was a child. It’s the medium I’ve had the most experience in and the most control over. Having done it for so long, I’ve got to a point as an artist where I feel I really excel in the technique.

When I was a resident at the Museum of Art and Design in New York, visitors would come up to my work and touch it. It made me laugh because then they would have this moment of realization that they were in a museum, where we do not touch the artwork!

Even when I kept samples of the materials nearby, they instinctively touched the finished works.

People relate to textiles in a more immersive way than other art media. It’s through our entire body and our sense of touch. Textiles are a material which we look to for protection and comfort. Our clothing is made of textiles; they have an immediate, physical and tactile connection to our bodies. This is what attracts me the most.

What or who were your early influences and how has your life/upbringing influenced your work?

When we were in elementary school, my Mom had an incredibly clever idea to hire an art teacher to be our babysitter. She was a single mother with three kids, so we oscillated between being latchkey kids and having this art teacher looking after us. As children, my siblings and I had this incredible opportunity to learn and play creatively, which had a profound impact on our lives.

During high school, I worked in the box office and lighting booth at an improv comedy club. The ethos of improvisation is one of possibility, influencing other pursuits in life. I always appreciated the expansive thinking going on around me. Whether it was my family, the improv theatre, going to college as a liberal arts undergraduate. There were always people pushing me to try something new and add an unexpected ingredient to the mix.

Growing up as a gay kid had a huge influence on who I was. Obviously, most gay kids don’t quite understand how they are different, yet a feeling of uniqueness is present. Many circumstances can impact how that plays out. Unfortunately, too many kids translate that difference into rejection, depression or even suicide. But others are able to turn it into a source of strength, as I did. An ability to switch between conforming to societal expectations and the acceptance of not conforming is built into that experience.

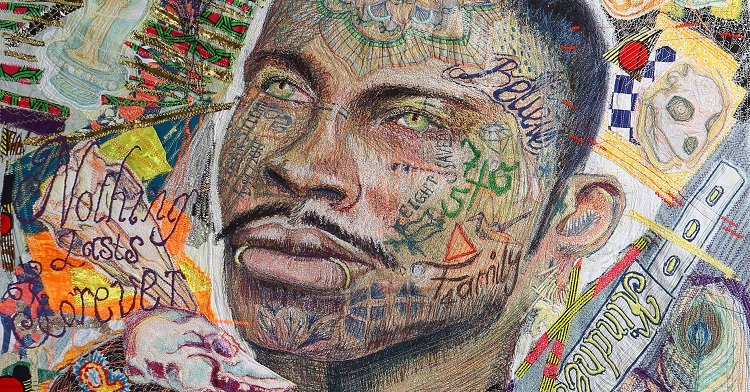

My identity as a queer man is central in my life and my work.

For me, and most LGBT people, love is an act of bravery. In 2018 there was a survey that found two out of three gay men fear holding hands in public. In my lifetime, I’ve had the question of whether or not I am “allowed” to love someone be debated by Congress and condemned by church ministers, even to the point of them inciting violence against myself and other gay men. This violence transforms something as universal as love into something political and dangerous.

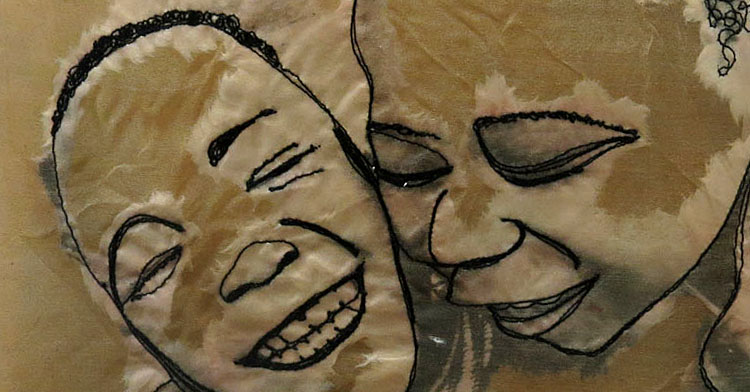

The act of making a quilt is slow, meditative and labour intensive. Dedicating all this time and effort to capturing a moment of love reclaims and honours the question which underlies all LGBT rights debates, ‘Is it okay to love and be loved, no matter who you are?’

What was your route to becoming an artist?

My career has been a series of accidents and amazing luck.

After college, I was working in regional theatres, mostly sewing costumes. I decided to move to New York City because I had no idea what else to do. I found work in a shop that builds puppets and mascots. I was making clothes for the walkabout characters.

Eventually, that job ended and I went to work for a costume shop which did work for Broadway theatre and film. I stayed there for about six years before leaving the theatre-world to launch my own menswear line and work freelance for fashion designers. During this time I ended up working for the Victoria’s Secret runway show and teaching at Parsons School of Design.

I also pursued an MFA in Design and Technology. The program was purposefully transdisciplinary and we were constantly encouraged to rethink the tools we used.

I wouldn’t have thought of it as ‘queering’ technology at the time, but in some ways, it’s become a thread running through all of my work. Design and Technology is a very straight male-dominated field. The idea of questioning norms and reimagining the way things can be mixed up, reassembled, redefined or be hacked is a common theme in the queer world. In retrospect, my work was attempting to grapple with these themes. I remember making a pop-up book for “St. Tom Of Finland” which mashed up Catholicism and gay leather culture. I also started mapping out my knitted films while in graduate school. It was all about throwing as many tools, ideas and forms into the blender and seeing what came out.

As my studio practice has evolved, that has become a more overt theme in the work I am doing. I am aware I’m a gay man doing “women’s work”. I am aware my medium of quilting is also the way we memorialise lives lost to AIDS.

I consider the work I do to be very technology-driven yet value the fact that my primary output is textiles, one of the oldest human inventions.

Asking yourself technical and conceptual questions

Tell us about your process from conception to creation

There are two streams of thinking going on in my work all the time.

There is a craft-based, technical inquiry where I am constantly asking ‘What I can do with the medium?’

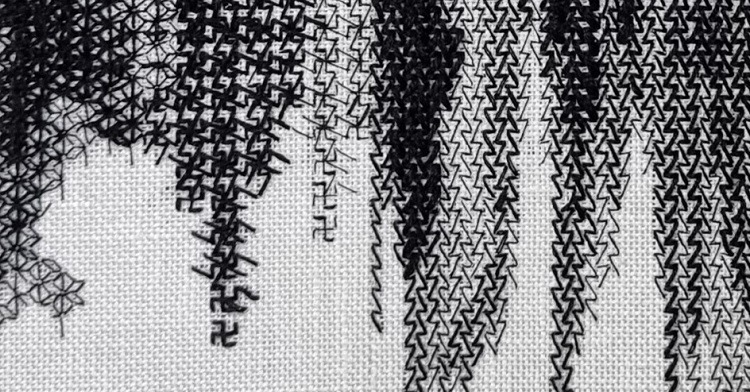

These inquiries are foundational for my thinking but probably less interesting to the audience. With the knit film pieces, it was asking ‘Could I even knit an animation?’ With the animated quilt, it was asking ‘How much can I degrade the image and it still remain visible when in motion?’

With the pixelated quilts, the questions are always evolving. Right now, I am interested in the hybrid colours which happen when we pixelate text. I am also interested in what happens when the pixels are not squares.

These explorations always lead to my other line of thinking, which is asking ‘What do these discoveries mean?’ and ‘What are the unique properties and outcomes of this technique?’ This is where the conceptual thinking ties in.

With the knitted film, I discovered I had a massive, heavy, and cumbersome film of knitted fabric. A film, which is a way of storing memories, but which is unwieldy. That resulted in the second knit film. I recreated an unwieldy, weighty and awful memory of my own, of being assaulted by a classmate in middle school. So now both the medium and the content were aligned with both being heavyweights, physically and mentally.

Similarly, with the pixelated quilts, I became fascinated by the way the images were clearer on the screen but more difficult to see in person. This phenomenon felt like a parallel for the way we relate to things online and in person.

I made a quilt called “Rescue workers at the factory collapse at Rana Plaza”. People often read online about the atrocities of the fashion industry but then make no changes in their fashion consumption habits. I hope the piece brings to the foreground that disconnect of what they see on screen and what effect it really has in the real world.

In my series of porn quilts, I wanted to highlight this shadowy but influential economy in the US. The Kardashians managed to use a home porn tape to launch a media empire. And yet we somehow are unable to see it or acknowledge the impact of this industry in the real world.

These two lines of inquiry, technical and conceptual, are always in constant communication. Often pieces sit dormant for months or years until the right technique comes along or until the thinking catches up with the materials and technology available.

Tell us a bit about your chosen techniques and how you use them

I primarily quilt. I start with photographs (often multiple photos collaged together) and use Photoshop to explore options for pixelating them. The planning stage of the quilts is very playful. Often I do half a dozen layouts before I decide on the right one.

From there, I take each pixel and turn it into a fabric. This means designing my own textiles so I can get the specific variations of colour I need. Once the fabric is printed I follow a straightforward traditional sewing and quilting process.

What currently inspires you?

I’m always inspired by the amazing people in this world.

A lot of bad stuff is going on these days and I can get caught up in it. But along with the bad stuff comes these amazing people who generate change in the world and who find joy in living, despite the bad. It’s easy to forget how amazing life is sometimes and it is these people who remind me and inspire me.

It’s easy to write off my work as just fluff which distracts from the much harder work we need to do on climate change and social justice. But I have days where I’ll be walking through an art gallery in New York and a show will just wash all that away and give me hope. I’ll be reminded that we can work on climate change at the same time as working on craft. They aren’t mutually exclusive. In fact, they need each other.

Involving my friends

Tell us about a piece of your work that holds particularly fond memories and why?

I have a tendency to put my friends into my work and it creates really joyful moments for me.

My first knitted film started when I ran into my friend Andrew Cornell Robinson and said: “do something silly”. I pointed the camera at him, recorded him and then a year or so later said: “I made this knitted film of you.”

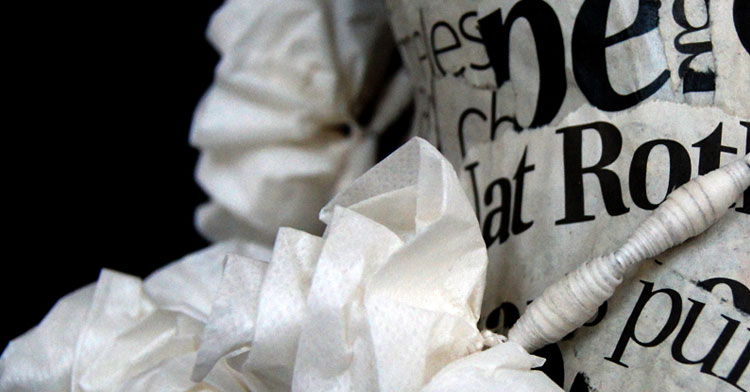

The quilted portrait I did of my friend Timo Rissanen is another that gives me joy. It was recently in a show, directly across the gallery from some of his own work. It made me smile so much at the opening to connect the two pieces in that way.

Being able to include people I love so much in my work is what actually makes the piece hold fond memories. I know it sounds clichéd but those moments, like surprising Andrew or sharing gallery space with Timo, make me really happy.

How has your work developed since you began and how do you see it evolving in the future?

It’s hard to label “when I began” because I’ve always been creative. There was never a moment when I said: “now I’m an artist”.

In fact, I think it’s the opposite in some ways. I find I am constantly re-convincing myself I’m an artist. I don’t know how to define an artist. Is it someone who has a professional practice? Or someone who just makes the work because they enjoy the process? Where is the boundary between ‘artist’ and ‘not-artist’?

I go back to my old work and just cringe at the mistakes or the lack of refinement, but then I also can track lessons in the pieces. I can see where I finally got a technique figured out or where a pivot in my thinking occurred. I think that dialogue with my old work is healthy. I’m my harshest critic and I have also learned to listen to curators and trusted critics when they offer feedback.

The longer I have been making work, the easier it’s become to see the themes in my work. I trust my instincts when working and often the threads that travel through my work are not really planned. I think it’s important for artists to constantly make work and keep moving forward. Stop and reflect, for sure. But if I sat around waiting for the answers to every question to be complete, I would never make anything.

The worst thing I can do is not start the project. There are plenty of unfinished pieces and pieces which will never see the light of day. But I did them until I learned what I needed until I sorted out some thought or process behind it.

With textiles, the work is slow. This allows for a lot of reflection.

Thinking about the process while doing the process, especially a slow process like quilting infuses value into the objects we make.

My friend Timo Rissanen cross stitches poetry. He says that the process is so slow that it allows the words to actually change as he works. He edits as he writes and the stitching is meditative in a way which allows his mind to reflect on the poems. I find that to be a beautiful idea that the work will evolve through the act of making it.

I am very interested in community engagement and the performative aspects of the work. I think that is the next evolution of the knitting and the animations. I have plenty of huge ideas for how to do that but that would require giant budgets and spaces, things I don’t have at my disposal right now. So that’s a direction I am inching toward but very slowly.

I’m interested in how textiles can be used for installations. Moving beyond the notion of just a quilt hanging on a wall and asking what would happen if they were used to build up the entire environment. I think these ideas might all be revolving around a desire to bring the ‘body’ back into the textiles. Like I said before, textiles are intrinsically linked to our bodies through clothing. I’ve been exploring what they can do and now it’s time to return them to the body.

What advice would you give to an aspiring textile artist?

Don’t get caught up thinking of your work as “textile art” and think of it as “art”. Textiles can be the primary medium but don’t let that limit the thinking.

Use whatever tool is the best for the idea. So, maybe your textile works need the addition of paint to change the texture. Maybe you can make use of the sound created by thread vibrations. Or incorporate the light and shadow interacting with the fibres. Maybe you can mix in some metal, or create a performance by using bacteria to change the appearance of the work over time. Whatever it is, add it in. Experiment!

For more information visit www.gregclimer.com and you can follow Greg on Instagram

Do you aspire to use high-tech approaches in your artistic process? Why not share your thoughts in the comments box below?

Comments