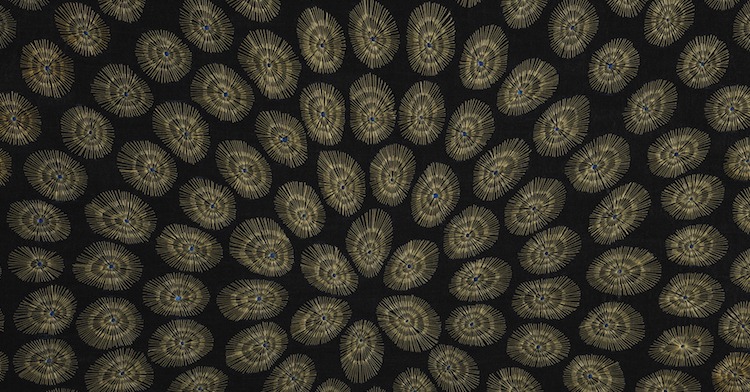

Katazome is a Japanese form of printing using a rice paste resist, resulting in a white pattern on a dyed background. Sarah Desmarais is utterly bewitched by this technique, which she blends seamlessly with her interest in abstract repeated patterns derived from nature.

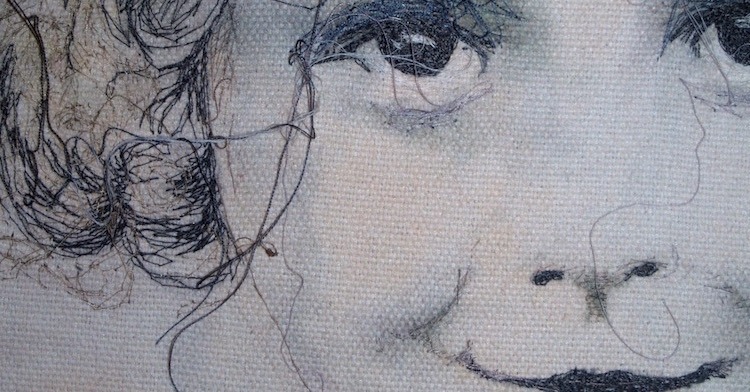

Sarah straddles the fields of fine art and domestic craft, keeping a foot in both camps and using each discipline to enrich the other. As a textile designer and fine art printmaker, her process moves naturally between periods of drawing and then printing.

Her abstract designs stem from drawings recording the natural world and coastal landscapes, which she turns into stencils cut with care and precision, in a slow, meditative way.

Katazome is a low-tech and small-scale process that allows Sarah to focus on the process of slow making and all of the mental health benefits this can bring. She believes that everyone can be a designer and maker, and that you’ll improve your well-being when you take the time to create beautiful handmade things.

Treasured heirloom textiles

TextileArtist.org: What or who were your early influences and how has your life/upbringing influenced your work?

Sarah Desmarais: I took an influential six-month trip to India when I was twenty, where I found that I derived more pleasure from the decorative arts of India than from the Western tradition of fine art painting.

After this, I continued on my path as a fine artist, but after several years I turned to abstraction and felt more able to incorporate influences from the textiles I loved; the art of the African Mbuti people was a major influence, as well as Indian maps, often in textile form, and early American patchwork.

What initially attracted you to textiles as a medium? How was your imagination captured?

When I was a teenager I was given some beautiful textiles that had belonged to my grandmother.

There was a patchwork blanket that she knitted during the Second World War, and a crazy patchwork dressing gown she made from silk dresses that she wore as a young woman growing up in the 1940s. I also inherited an exquisite hand-embroidered shawl, a cotton slip with lace edging and a hand-embroidered silk slip, probably all being from the Victorian era.

These were treasures to me, although I think all these items suffered a little from being worn to parties in my later teenage years.

My mother’s competence as a dressmaker was also an influence; she could run up a new school skirt for me in an hour. She taught me needlework and dressmaking skills, although I never achieved her levels of proficiency. And she instilled in me an appreciation for homemaking and aesthetically beautiful, tactile domestic environments.

Despite this background, I grew up in a culture that valued fine art over applied and domestic arts and crafts, so I didn’t seriously consider studying textiles at this point.

What was your route to becoming an artist?

I have two memories of defining moments as a school pupil.

One is of creating a seascape picture in my first year of school; I was inspired to cut a seagull shape from white sticky-backed paper and to collage it onto the painted sky. This is my first memory of the creative excitement of working with diverse materials. Coastal landscapes and skyscapes continue to inspire me today.

The second moment, which probably occurred later the same year, is of being presented with my first box of watercolours at a school fete as winner of the art prize. I clearly remember deciding at that moment, with the paintbox in my hands, that I would become an artist.

The benefits of slow making

Tell us about your process from conception to creation

My process has varied considerably throughout my career.

My work spans both the textile art and fine art fields, and these days I am more comfortable about this than at any other point in my career. I feel the approaches in each discipline enrich each other.

Sometimes I think of myself as a textile designer maker, and in other periods I proceed as a fine art printmaker, but there is a great deal of overlap.

It is typical for me to spend a couple of days drawing in the landscape with pen and ink, then I make experimental translations of my drawings into prints using an etching press. I spend time cutting stencils based on my drawings and print them as fabrics.

I’ve recently moved to the south coast of the UK and I’m lucky enough to have a studio at home. I love to walk to the beach, observing flocks of starlings and vast cloudscapes. Here, seals swim along the estuary. I like to stop en route and draw, recording visual impressions and sensations in an abstract way and enjoying the properties of ink, bamboo and Japanese paper.

I find the process of stencil cutting very meditative, and I’m bewitched by the katazome print process and the tactile delights of the textile medium.

However, I’ve found my relationship to textile production conflicting.

The processes I use are so slow that it’s impossible to sell what I make for a living wage. I also feel strongly that owning more stuff is not a way forward in the current environmental crisis, and I have no wish to participate in the mass production of textiles for interiors or fashion through selling my designs.

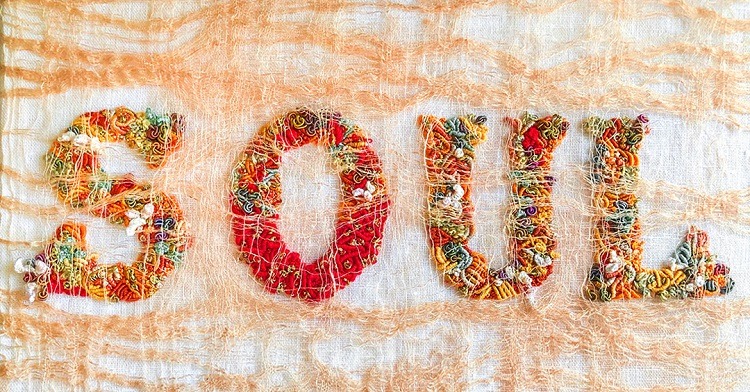

One solution has been to focus on process and the potential well-being benefits of slow making.

I received Arts and Humanity Research Council funding for three years (2012-2015) to undertake full-time research on manual creativity and mental health. I found this project extremely rewarding. The workshops I’ve run for amateur makers all have quite a strong well-being element to them.

I feel there is a kind of quiet activism in encouraging people to make their own things. This is partly because of the environmental considerations, but also because I think that everyone can be a designer and maker; we don’t have to make ourselves reliant on mass production to have beautiful things.

Tell us a bit about your chosen techniques and how you use them

When I had the chance to explore a collection of Japanese paper stencils, during a residency at the Museum of Domestic Design and Architecture in London, I became smitten by the art of katazome stencil dyeing.

This process involves hand cutting paper stencils and printing a rice paste resist through them onto silk or other fibres. The fabric is then dyed and the resist washed out to leave a white pattern on a darker background.

For me, this is the ultimate small-scale textile print technology. The materials are safe and can be used in a domestic environment to produce small quantities of printed fabric.

The method is extremely reliable despite being low-tech. The results achieved by Japanese artisans are extraordinary. And I like the freedom from print studios, industrial-scale equipment and toxic chemicals.

What currently inspires you?

I find inspiration in what emerges when a traditional print technology like katazome enters into a dialogue with radically different traditions.

My mark making and drawing techniques come from diverse Western traditions, including observational drawing and mid-twentieth century American and British abstraction.

At the same time, I think there are no ‘pure’ traditions. Western artists have been strongly influenced by the Japanese tradition, especially from the late 19th century onwards, and Japanese traditions derive from or have been influenced by Chinese, Indonesian and European models.

The abstract paintings of Agnes Martin and the recent work of Rebecca Salter RA are also major influences, alongside many types of Japanese textile art. And at the moment my slow, labour-intensive processes inspire me to create a mood of stillness in my work.

A respect for nature

Tell us about a piece of your work that holds particularly fond memories and why?

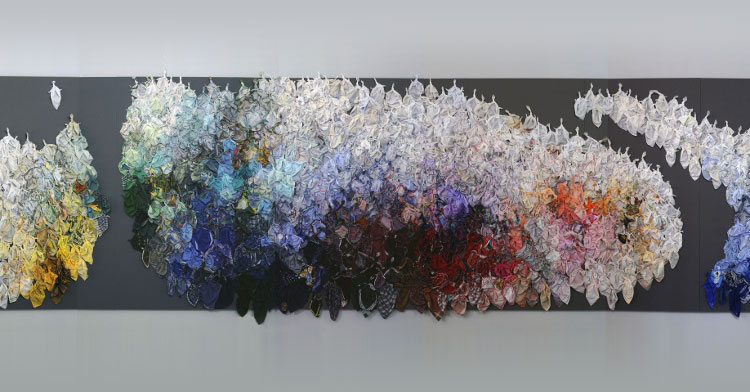

My work took a significant step forward when I began to consider the potential of my textile works in a fine art/installation context, rather than as applied art or craft.

I produced some experimental transparent silk gauze panels using designs derived very directly from drawings made on the spot in a variety of coastal landscapes.

These works were inspired by the invisible but crucial networks of roots and fungi below our feet, and the idea of the ‘underland’ (described in the book Underland: A Deep Time Journey by Robert MacFarlane).

This was the point at which I started thinking about katazome as a way of printing my drawings on a large scale. I’m still building on these pieces of work with an environmentally-themed exhibition in mind.

How has your work developed since you began and how do you see it evolving in the future?

I’ve always preferred to jump from one medium to another in order to pursue an idea. This stops me from feeling constrained by a particular visual language, product or way of working.

The trajectory of my work may seem erratic; I’ve jumped from figurative landscape painting in the 1980s, to abstraction, and now to textiles.

I think the distinction between textiles, drawing and printmaking is increasingly blurred for me. Certain threads run throughout, including the importance of immersion in nature, a fascination with materials and process, and an interest in the emotional effects produced by pattern and repetition.

As I grow older, I’m more and more interested in producing work that creates a mood of stillness and an understanding of the spiritual. I hope that my textiles, whether in fine art or applied art context, express ideas related to a respect for nature.

11 comments

Sharron

Thank you for this article. Sarah, I really appreciate your explanation about process and the benefits for health, plus that lovely bit about quiet activism. I was very ill when your workshop with TextileArtist.org Stitch Club took place, however, I managed to slowly persevere and enjoy the delicate and delightful process. I have to say that the time spent gaining inspiration from your work (and your clear instructions) genuinely helped me through a physically demanding time. Thank you!

Rhonda Tomerini

Do you still use rice paste resist and how do you make it. In your workshop requirements you ask for sodium elgenate powder, I can’t get that for the workshop so was wondering if Agar-agar Seaweed would be ok to use. Thanks I love your work and can’t Waite for the workshop on textileartist.org. Xx Rhonda

Sarah Desmarais

Also to answer your question about rice paste, yes, I use it for nearly all the printing I do, but it’s a bit slow to make and one of the ingredients is hard to get hold of, so for my Stitch Club workshop I experimented until I found more easily available materials that would do the same job on a small scale. I hope you’ll feel inspired to have a go making the traditional rice paste and have a go with that if you enjoy printing with my simpler substitute.

Very best wishes,

Sarah

Sarah Desmarais

Hi Cornelia,

Thanks for your thoughts. Using a stencil to produce repeats is endlessly fascinating – I hope you get a chance to try it out –

Very best wishes,

Sarah

Sarah Desmarais

Hi Mariette,

Thanks very much for your appreciation – I’m glad it resonates with you!

Very best wishes,

Sarah

Sarah Desmarais

Hi Margot,

Thanks for your appreciation!

Very best wishes,

Sarah

Sarah Desmarais

Hi Rhonda,

Thanks for your appreciation, and apologies for my slow reply. If you contact me via my website sarahdesmarais.com I’d be very happy to see if I can find a source for you online where you live. It’s very widely available on amazon and eBay and also through textile dyeing supplies and I’m really happy to do a search for you.

Hope that helps!

Very best wishes,

Sarah

Cornelia Payne

Just love it! I never thought stenciling could be so interesting and creative using repetitive patterns and with simple methods as well. Must explore this technique soon.

Thank you so much for sharing.

Mariette

How inspiring to me. I have always loved textiles since childhood – learnt at a young age to sew and later completed different courses. I studied fine art and are always looking for ways to marry fine art and textiles. Your work and approach to mental healing really resonates with me. Art therapy interests me much. Thank you for sharing your beuatiful work.

Vicky Bilton

to try this out……

Margot

Gorgeous