Many of us can remember taking part in science fairs back in our school days, with poster boards, live experiments and scientific talks to explain how things work.

But imagine if you had to demonstrate scientific phenomena using your sewing machine. Exactly how would you go about it?

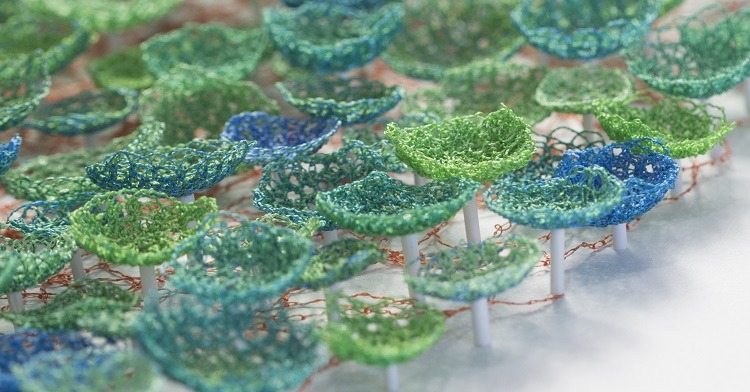

Australian artist Meredith Woolnough was presented with just such an opportunity when she was asked to illustrate the beauty of human cells. When she received the invitation, she wasn’t sure it was an opportunity, so she answered the call with a bit of trepidation. But after Meredith was partnered with a scientist who researched embryonic cells, she entered a whole new world of stitch and science.

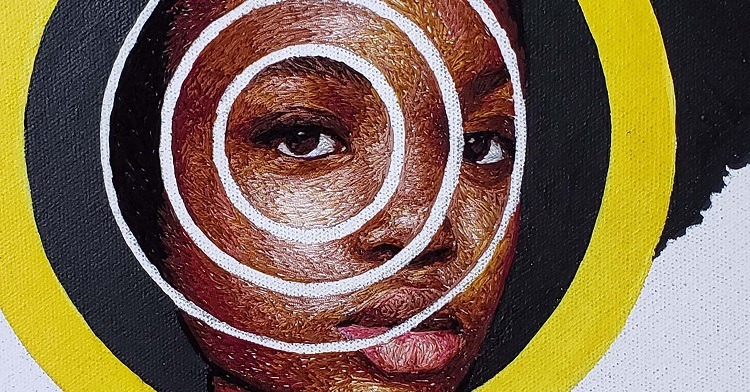

Meredith was already known for her elegant, freehand machine embroidered drawings showcasing the beauty and fragility of nature in knotted threads. And her use of soluble materials in creating her work is somewhat akin to scientific experiments. She’s never fully certain what the outcome of her stitch explorations will be once she washes away the background.

Inspired by the patterns, structures and shapes found in plants, coral, cells and shells, Meredith brings nature to life in ways we’ve never seen before. That’s why we’re thrilled she’s sharing an insider’s look into her freehand machine embroidery process, along with tips on working with soluble fabrics. She’s also revealing the novel way in which she exhibits her work.

Enjoy this remarkable exploration of scientific stitching.

Navigating new territory

Meredith: I was first introduced to freehand machine embroidery (also referred to as free-motion embroidery) in a very basic way in a surface design class during my last year at the University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia, in 2006.

I thought it was an interesting way to draw with huge creative potential. But there wasn’t anyone at the university or other artist I knew who could help me explore it further. So, I started experimenting and I’ve been fine-tuning my practice ever since.

I later learnt about water-soluble fabric, and I thought it, too, was so innovative. I decided to combine it with freehand machine embroidery and discovered even greater room for creative experimentation. It was a way to liberate embroidery from its base cloth and create sculptural embroidered drawings.

“Pretty much everything I learnt was through trial and error.”

Meredith Woolnough, Textile artist

At first, I really didn’t know what I was doing. I barely knew my way around a sewing machine, and most of my early experiments just turned into gluey tangles of threads.

Once I’d sorted out my preferred materials, machine settings and stitching techniques, it all fell into place. I was able to really start playing, and that’s when the magic happened.

Moulding magic

I started to learn what was possible, especially how to stitch designs that would hold together in a predictable way once the base fabric was dissolved. And I developed ways to mould and shape the embroideries to create sculptural forms. Magic indeed!

So many of the techniques and practices I use today were developed during that first year of focused study. My early experiments laid the foundation of my current practice, and I fell in love with this simple but highly versatile embroidery technique. How could I not?

Exploring science with stitch

The more I work with natural forms, the more I find myself drawn into the science of nature. I am fascinated by the way things are built, the way they grow and function. I often find myself marvelling at the perfection of a single leaf or the phenomenal beauty of a coral reef. It can be quite overwhelming at times, almost spiritual.

I also find the more I learn about various plants and animals, the more I realise I know so little, and I then want to learn more.

“It’s a wonderful cycle of learning, discovery and inspiration.”

Meredith Woolnough, Textile artist

My design ideas often begin with a simple inspiration point found in nature, such as a plant or animal that sparks my interest. I love to do field work sessions where I go out and find, photograph and collect various specimens to study. These sessions can be as simple as a casual walk around the garden to purposefully planned field trips.

I like to immerse myself in nature whenever possible and see what catches my imagination.

Research is a highly valuable part of my process, as it helps me become very familiar with my subjects. It’s so much easier to draw something I know intimately.

Whenever possible, I like to work from life. Nothing beats observing and interacting with a real thing. Sometimes I’ll collect specimens, but I’m very careful to only collect things with permission. If I’m studying something I cannot collect, like coral or shelled animals, I take lots of reference photographs instead.

Notes & drawings

Many of my collected specimens are fallen leaves, common household plants or weeds. I’m not snobby with my choice of subjects. Even the humblest plants and animals have beauty and interesting structures.

I also keep sketchbooks full of research notes and drawings, and I have vast libraries of reference images I’ve gathered over the years. All of this collected and collated research helps inform my final artwork designs.

The creative process

Once I know what to stitch, I sketch my final design to scale on paper. I also choose a colour palette from my ever-expanding thread collection.

If I’m using a new combination of colours, I’ll make a little stitched swatch to make sure the colours blend. I love to incorporate colour blending in my work. I can create all kinds of new colours and textures by blending threads while stitching.

I transfer the basic outline onto a sheet of water-soluble fabric and stretch a section of the design in an embroidery hoop, ready to stitch using freehand machine embroidery.

Shaped threads

Once my embroidery is completed and well connected, I wash the dissolvable base fabric away leaving just the stitched drawing behind. The thread drawing is then left to dry. It can also be shaped or moulded while drying to achieve more purposeful sculptural forms.

There are two main varieties of water-soluble fabric: the clear film variety and the washable web variety (that looks like interfacing). Many artists use the clear film variety very successfully, but I hate it. It stretches, tears easily and is difficult to wash away. Often it turns into a big gluey mess – I don’t recommend that variety for this style of embroidery.

I prefer the washable web variety. It’s strong enough to use a single sheet as a base material on its own, and it washes away quickly and easily in hot water. It does have some limitations and quirks, though. For example, it tears easily. But I have developed techniques to prevent or repair tearing, so that is rarely a problem for me anymore.

“It’s all about learning the possibilities and limitations of your materials.”

Meredith Woolnough, Textile artist

Shadow mounting

Most of my works are displayed in box frames, and I have a specific shadow mounting system.

I secure the embroidery using fine pins that allow the embroidery to float away from the backing board. This display method is a hugely important and iconic part of my work. For me, embroideries that are mounted flat lose some of their magic. I prefer my embroideries to appear to be floating in the frame showing off their beautiful lace-like nature.

I experimented with so many crazy ideas before I settled on this process. I now teach an online course showcasing my shadow mounting process, as I believe it can be applied to many forms of textile art.

“Shadow mounting allows the artwork to cast beautiful shadows and show greater depth and dimension.”

Meredith Woolnough, Textile artist

Favourite sewing machines

I work with two sewing machines. Almost all my work is embroidered on a long arm machine (Bernina Q20) because it has lots of room to move. It’s more ergonomically correct than a standard machine, which is important as I stitch for many hours a day.

I also have a large domestic machine (Bernina 735) which I use for zigzag stitching. The long arm can only do straight stitch freehand work, so I need to go back to a regular machine if I want to do anything fancier.

I prefer to work with machine embroidery threads because they are nice and strong, which is important for this type of embroidery. Machine embroidery threads also have a lovely subtle lustre.

The art of cells

I was fortunate to be invited to participate in ‘The Art of Cells’ project developed by Gibco (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Its aim was to explore the amazing beauty of cell research by pairing scientists from around the world with artists who would artistically interpret their scientific findings.

The scientists were first asked to write a ‘love letter’ about why they love the cells they research. They shared those letters with the artists, followed by further discussions.

I was paired with the lovely Dr. Marietta Hartl who researches early embryonic cell cultures. Her love letter described how amazed she was seeing the beauty of cells with her own eyes and how she felt like a child at Christmas peering through her microscope and watching cells develop over time. She felt honoured to learn more about nature by watching cells build sophisticated structures from scratch.

Dr. Hartl ended her letter by saying watching me experience the joy of discovering cells brought nearly the same joy as her own initial experience and that there can never be enough people falling in love with their cells.

Trepidation & pleasure

I went into the project with no idea what I would be making, and it was quite scary. But I was pleasantly surprised to see how incredibly beautiful cells could be. The microscopic images were like something from an alien world, glowing and pulsing with life. It was amazing to think those clusters of embryonic cells were the starting points of life.

The campaign was such a great project. It pushed me in new directions, and it was an incredibly interesting experience to work collaboratively. I hope to do more of these types of projects in the future.

For this project, I took part in a short video showcasing our collaboration and how I created my work.

9 comments

concepcio prat

FELICIDADES. gran artista son obras de arte, gracias por publicarlo,los ojos se alegran mucho de verlo. salut i larga vida.xita

Donna

Absolutely amazing & inspiring! Sometimes it IS the details.

And the collaborative effort was challenging & fun. I want to see more!

I want to try it! Thank you.

Meredith Woolnough

Thanks so much Donna for your lovely comment. Yes, it is all in the details!

Sharron Deacon Begg

Meredith, I love your work, your methods and love that you have found this fabulous world to explore.

I am an old free-motion machine embroiderer and am thrilled that you have found this love early. Thank you for this article.

Threadpainter

Meredith Woolnough

Thanks so much Sharron. I am so glad I found this love for embroidery as well. I hope the love affair continues for many years to come.

Elaine Salt

I had seen Meredith’s incredible embroideries before but never ceased to be amazed by them. Such beauty and artistry created with such simple materials. A very talented young woman.

Meredith Woolnough

Thank you so much fo your kind comment Elaine.

Monik Desgranges

Magnifique travail très frais et aérien bravo à l artiste pour ce travail rafraîchissant

Meredith Woolnough

Thank you Monik