Tattoos have become increasingly accepted as an art form – one you can carry everywhere with you – so it’s no surprise that the colour, characteristics and artistry they express have caught the attention of contemporary textile artist, Oliver Bliss.

When studying for an art degree, Oliver’s teacher persuaded him to spend his student budget on a sewing machine. He duly purchased one and committed to become an expert at machine stitching, or free motion embroidery. In his work he explores themes such as gender, sexuality and power and embellishes his machine stitched pieces with hand stitch and appliqué.

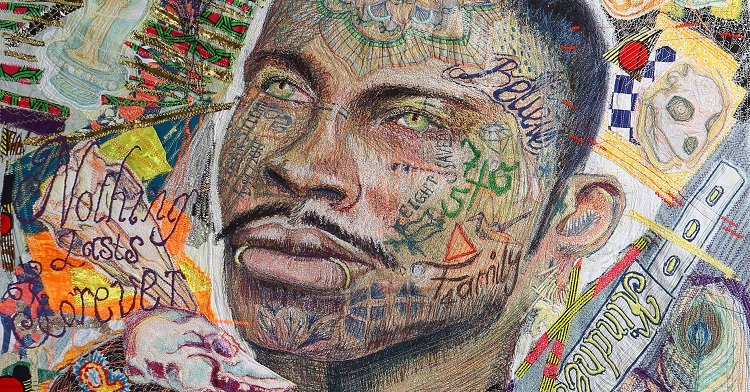

His series #Softlads combines the traditional approach of tapestry in portraiture and craft with the contemporary twist of machine embroidery and modern imagery to examine how and why people promote images of their bodies on social media.

You may or may not have a penchant for torsos and tattoos but Oliver shows us how beauty, art and activism can be combined to create a powerful and positive impact on global culture.

Committed to textiles

Tell us about your background in textiles: have you been influenced by family, teachers or employers?

Absolutely! My biggest influence was when I was at Manchester Metropolitan University and I visited the Whitworth Gallery for the first time.

I discovered Alice Kettle’s triptych, The Three Caryatids (1989-91) and saw the incredible amount of thread that she used in her work. The beauty of those layers converted me from working in oils to wanting to work in thread.

My tutor convinced me to use my student loan to purchase a sewing machine instead of spending the money on booze. It was a pivotal moment, and from then on I became committed to a textile-based practice.

I had no formal training other than the support of my dorm mate who was on a textile-based course. She showed me how to set up my sewing machine and the rest was trial and error. That machine was with me for 15 years.

I had come out during sixth form, so by the time I’d joined the Art and Design (Fine Art) foundation year at Hereford College of Art and Design I was more settled in my sexuality and keen to develop my understanding of queer culture. I was all about discovering my identity and sense of self.

I was really drawn in by the idea of men sewing and using mixed media to blur the boundaries surrounding gendered expectations and social norms.

I developed my practical skills through my art and design course. It was the best educational experience I have had to date. My teacher, Clare Neil, introduced me to Jenny Saville, whose work on the Manic Street Preachers’ album cover, The Holy Bible, displayed her triptych Strategy (1994). I learnt about all her influences through the course, and that introduced me to artists like Peter Paul Rubens, Mark Rothko and Francis Bacon.

Bacon’s piece Triptych August 1972 at Tate Britain is one of the most moving images. I would stare at the painting for ages while people walked past like it was background noise. Friends and family literally had to push me on to the next room of the Tate. I couldn’t understand why they weren’t as fixated with the artwork as I was. For me it represents a timeless love and a sense of grief, which was heart wrenching.

Works in triptych have been influential over the years and my most recent inspiration has come from Oskar Kokoschka’s The Myth of Prometheus at the Courtauld Gallery. The scale and the energy incorporated into the work is visceral.

Clay and drawing

My parents were a strong leading factor in encouraging my creative interests. My father was a sculptor and we would sit together as a family and make clay pinch pots, coil pots, figures and tiles. He was also good at providing critical feedback on my basic drawings from a young age. I still vividly remember trying to draw a grandfather clock and him scribbling corrections over the top of it.

At the time I found it frustrating, but once I started school, teachers told me I had a natural talent for drawing. I didn’t, I just had a lot of early practice. Kids were more often encouraged to kick a football around, but that didn’t interest me or my father, so clay and drawing was our way of bonding.

On family holidays we always visited cultural sites, such as historic buildings, galleries and museums, which had an impact on me. In my teens my mother would take me to London where we would do a circuit of contemporary galleries together.

The most important show I saw was Boys who Sew by Janis K Jefferies in partnership with the Crafts Council in 2004. They had a range of male artists working in thread and it blew my mind.

Textile collective

I am part of seam, a contemporary textile collective based in Bath, England with a mix of emerging and established embroiderers, printers, knitters, weavers, dyers, fashion designers, eco-designers, makers and artists.

I’ve been inspired by being in a group of people who are all equally passionate about sewing. The members have similar yet very different areas of knowledge and expertise and we’ve been able to trade in ideas and methods of approaching our work. We had an artist residency at the Holburne Museum, which transformed my practice and encouraged me to experiment with further installation works.

Are there any particular topics or themes that inspire your work? Why is that?

Identity politics has always been of particular interest to me as it helps me understand myself and the world around me; themes such as gender, sexuality and power. I like art that moves beyond being aesthetically pleasing or well-constructed, and that has an open voice, generating conversation and connection with multiple points of view.

I really appreciate abstract artists who achieve a sense of beauty and balance in a chaotic piece. I find it challenging to distil themes into their most accessible forms and it’s something I strive for in my creative process.

The best example of this for me is the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe in Berlin, a collaboration between architect Peter Eisenman and Buro Happold. The work consists of a 19,000-square-metre (200,000 sq ft) site covered with 2,711 concrete slabs. It is the most powerful and important piece of work I have ever seen.

The slabs engulf you as you physically walk down into its brutalist maze. You get that sense of oppression and despair, and yet, by contrast, it’s uplifting to see children using the space like a giant playground. The work is entirely abstract whilst being layered in universal emotional concepts and is a fully immersive experience. Finding work that is edifying in some way is very inspiring to me.

How do you develop ideas for your work?

I regularly use sketchbooks and have several for different purposes. I have one which is more of a scrapbook, one for jotting out initial ideas and several for developing work. I have several different sizes so that if I want to work bigger, I have the freedom of space to go big or hash out several ideas.

If I’m travelling, I will often stop to jot something down in the moment to record an idea. It might go nowhere but if I don’t do it then I forget it and move onto something else. Occasionally through this process something will grab me, and I’ll trial and experiment with no particular outcome.

The Hereford foundation course taught me to stop thinking about final pieces: it’s too time consuming. Just experiment and play, give yourself the space to allow this in your process and it can result in much more interesting work. I forget this at times, especially if I am in the process of making bigger pieces like the #Softlads series, as I’m a starter-finisher and hate to abandon a job.

I live by the mantra ‘we’re all going to die at some point, so get on with what interests you and ignore any self-doubting voices’. They don’t serve you and will prevent you from just starting.

Layering thread

Tell us about your process, from conception to creation.

I often scroll through Instagram – I love its immediacy and its visual expression, where people are sharing parts of themselves in an open and democratic way. I generally ignore trends but instead seek the topics I am interested in. If I’m looking for a specific term or idea, I’ll investigate a hashtag. You can be sure someone, somewhere has thought of it and shared something, and from that ideas snowball. I use it in conjunction with Pinterest.

My process of trial and error can be about expression, textures or techniques, depending on the project. I might make samples and swatches to see what combinations I think work. I like time to reflect on what it is I am interested in and why I am drawn to certain subjects and themes. I’ll note this down in a free-writing, five-minute exercise; the discipline helps me articulate myself and from that a project might come out.

If I am working on a bigger piece, I might use a few methods to work at scale. I like to work freehand, drawing with Sharpies and sketching out an initial idea. I have my mother’s old acetate projector and if I’m working on a figure, I might do several layers of acetate as I like to look at the figure’s values and on another layer look at details of the face or tattoos. I might also experiment with colour blocking to see which layers work well together.

Once I’m happy, I draw it out with Sharpie pens onto cotton in my studio. Sharpies have different thicknesses which can replicate the width of thread very well. This creates a cartoon draft of the image, which I can work over. I work in layers of thread, so these are all hidden by the time the work is complete.

Using transparent layers in apps like Photoshop Mix and Da Vinci Eye, in conjunction with my original sketch, I can ensure that the face portions have scaled up correctly. I then sew line grids across the cotton so that the material is reinforced with squares. I will also add stabiliser to larger sections, but not always, as additional layers appliquéd on top might make it too thick.

Sewing machines don’t like a lot of layers as I’ve learnt to my annoyance, after breaking three machines with my more ambitious work.

With each layer of thread I sew, my actions will stretch or tighten the warp and weft of the cotton. There are areas which I want to make curving circular marks, and these affect the material the most, so I hang the work to see how much an area has been affected by this process. Sometimes I then have to cut the design into sections and rework into them so that the undulation of the material is minimised.

From a distance my work can be confused for paintings, which is intentional. I want people to be surprised to discover they are textile work, so I incorporate movement, which helps show it’s not painted on stretched canvas.

What fabrics, threads and other materials do you especially like to use in your work?

I love going to charity shops and getting a range of random materials, especially things which are discarded. It’s also partly to be more considerate about the environment.

Sharpies are one of my favourite tools to use and they are very practical, though I recently learnt there’s no guarantee that they’re vegan as they don’t disclose all the detail of what goes into their dyes and pigments.

The seam collective has really helped educate me more about sustainability in my practice. I always ask people to give me their scraps and they love to see them embedded in my work. I have learnt, however, to keep this to a minimum to avoid too many thick layers. My sewing machine repair man said I drive my sewing machines like a 4X4 when they only have the power of a mini!

Contemporary masculinity in thread

Tell us a bit about your #SoftLads project

#SoftLads is my first solo series of pictorial, contemporary tapestries. Historically, tapestries have depicted social scenes, events, and notable figures. They were often commissioned by nobles or made to honour war heroes. People depicted with tapestry perpetuate their gender and status through styles of clothing, and symbols of power and wealth to reflect who they are.

The #SoftLads portrait series explores notions of contemporary masculinity. Themes span from contemporary hero worship, body image, the impact of social, democratic celebrity, activism, sexuality, gender variation and history of identity. The series explores how and why we generate images of ourselves and promote ourselves on social media. I’ve used textiles as a nod to historic approaches in portraiture and craft, with a contemporary twist.

I chose Instagram (representing a global social network) to collect a sample of portraits of men. #SoftLads explores their facial and body tattoo portraits and celebrates how they curate themselves online. These images were used as a starting point to represent the portraits in tapestries or quilts. So far I have completed five pieces, with a sixth currently in development.

My work has been on a tour to Stryx Gallery, Birmingham in October 2021 as part of SHOUT! Festival. It then went to Henry Sandon Hall in Worcester in February 2022 and we launched a poetry anthology also called #Softlads.

The Word Association was a partner in the tour and delivered workshops in creative writing in response to the artworks. The style of poetry produced is called Ekphrasis (from the Greek meaning ‘description’). It’s inspired by a work of art where the poet uses text to amplify and expand the original object’s meaning. Over 50 participants submitted creative writings for the anthology and many performed at the launch in February. The performances and footage of ideas in development were recorded and are available on YouTube.

With Arts Council Funding we then exhibited the work at The Hive in Shrewsbury during Pride month. I sold postcards and the anthology on my Etsy shop.

Do you have a favourite piece and what makes it your favourite?

My favourite piece is Artist/Activist, mainly because it’s centred around the model Yves Mathieu East who I found on Instagram. He’s an activist, musician, a full-time model, and spends his spare time volunteering at homeless shelters, LGBTQ runaway centres, and senior citizen homes. He also rescues pit bulls from the streets or from fights, fostering and rehoming them. In my tapestry, a golden light is shining upon him as he manifests his future. For me he is a visionary, as an artist as well as an activist.

The images surrounding him are all based on tattoos across his body. I really loved the idea that he carries his memories upon him everywhere. They are visual clues and symbols, rich with deep and personal meaning to him and anyone who has shared those moments with him. I wanted to honour his memories and to celebrate his life.

There aren’t many depictions of black gay men that are in public collections, and I hope that Artist/Activist will one day make it into one.

I love the piece because the making of it has helped me to grow in my understanding of how to construct this kind of work. Producing his facial features at that scale entirely from thread was really challenging. I drew on a lot of theory to ensure the values of his face and the skin tones worked.

What advice would you give to an aspiring textile artist?

I’m weaker at planning; I like it as part of the creative process, but I much prefer just getting on with it. For longer projects, however, you really need a schedule and milestones to help keep a focused structure.

As a creative person I know there is a sense that planning can stifle creativity. It’s an excuse I use because, in reality, my mind wants to wander, I can become distracted by other ‘life’ tasks, or I’m overwhelmed about how to begin.

I found reading Flow by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi really helped me to identify my issues. The main points I’ve taken away are that you need to be clear on your goals, remove distractions and stress, allocate a clear set of achievable targets for yourself, and the work should be stimulating and challenging within a threshold that isn’t too demanding.

I would also recommend trying it to find ‘your people’. Instagram has worked well for me, but meeting like-minded people in person is still an enriching and rewarding way to grow and learn.

How do you think your work will evolve in the future?

My residency with seam collective has shifted my ambitions radically. I want to work more three-dimensionally with installation-based work, which will be a challenge because of issues with transport and storage. I’m not going to let that hold me back though. I want to queer more white cube spaces and make immersive landscapes which claim and take over.

I aspire to tour #Softlads nationally: it will be titled #Softlads on Tour! Another nod to the ‘lads, lads, lads’ type of culture. I want to be able to showcase more of the writers’ work and enable them to do more readings of their poems. I also want to be able to make a new anthology, which pulls together new voices and I’m looking forward to securing partnering venues nationally to be hosts.

3 comments

Ellen Cunningham

Scotland has had its share of modern designers and makers of embroidery , collages,and banners. See Malcolm Lochead, Who trained at Glasgow School of Art in the 1960s and carved an outstanding career in embroidery and textile work.

Ellen Cunningham

His work is remarkable.Remember that Opus Anglicanum workers were all men and that women were never encouraged to do goldwork. It was a closed shop and you had to be a man to join the guild.Many men were the tapestry weavers of the past and there was a tradition of men wounded in past wars of making small patchwork pieces while hospitalised.

Jayne Terry

Oliver needs a stronger machine ! Lol