Not being able to stitch due to illness or injury is as crippling to the mind as it is to the body. I learned this firsthand in 2021 when a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis came crashing into my world. My hands and wrists had become so inflamed, I couldn’t twist the top off a water bottle, let alone hold a needle and thread.

Fortunately, I found a doctor who understood both my disease and artistic heartache, and together we figured out a plan to regain the use of my hands. Today, I stitch more slowly, and I can’t last as long, but I’m thrilled to say I’m still stitching.

I also have a new-found appreciation for my fingers and joints and the dexterity I still possess. As they push a needle through fabric, knot a thread or snip a frayed edge, I’m grateful for their continued partnership in helping me tell my stories in stitch.

We’ve gathered five textile artists who have also experienced illness challenges, and they’re sharing the works they created in response to those journeys. They describe how stitching helped support them during and after difficult times, as well as the physical and emotional impact stitching had in their recoveries.

Sonja Hillen starts us off with her stitched response to her husband’s cancer journey. Michelle Ligthart then shares her stitched book chronicling her decision to have her breast implants removed. Haf Weighton follows with her scary and ironic experience of becoming ill while working on a textile commission for a hospital. Linda Langley next describes picking up needle and thread to process her mom’s breast cancer diagnosis. And Jane Axell closes by sharing how mindful stitching helps keep illness at bay.

We’re grateful to each of these artists for sharing their stories and work in such candid and inspiring ways.

Sonja Hillen – A caregiver’s view

When a life-threatening diagnosis comes out of nowhere, it’s not just the patient who’s tossed about. Caregivers also experience their own challenges. Such was the case for Sonja Hillen when her husband was diagnosed with cancer and given about eight years to live. Their children were 12, 10 and 6 at the time, and it would be a five-year odyssey for them all. Fortunately, a stem cell transplant was successful, and Sonja’s husband is cancer-free today.

Countless doctor appointments and scary hospital stays happened across those five long years. And Sonja turned to stitch to help process her and her husband’s unfolding story.

‘We processed all the doctor conversations and treatments while trying to keep the family going as best possible. I felt like I was living on adrenaline, so I started stitching to help me rest a bit while sitting by my husband’s bed. For me, embroidery means working with the human dimension, and when I’m stitching, I’m in a bubble where time slows down.’

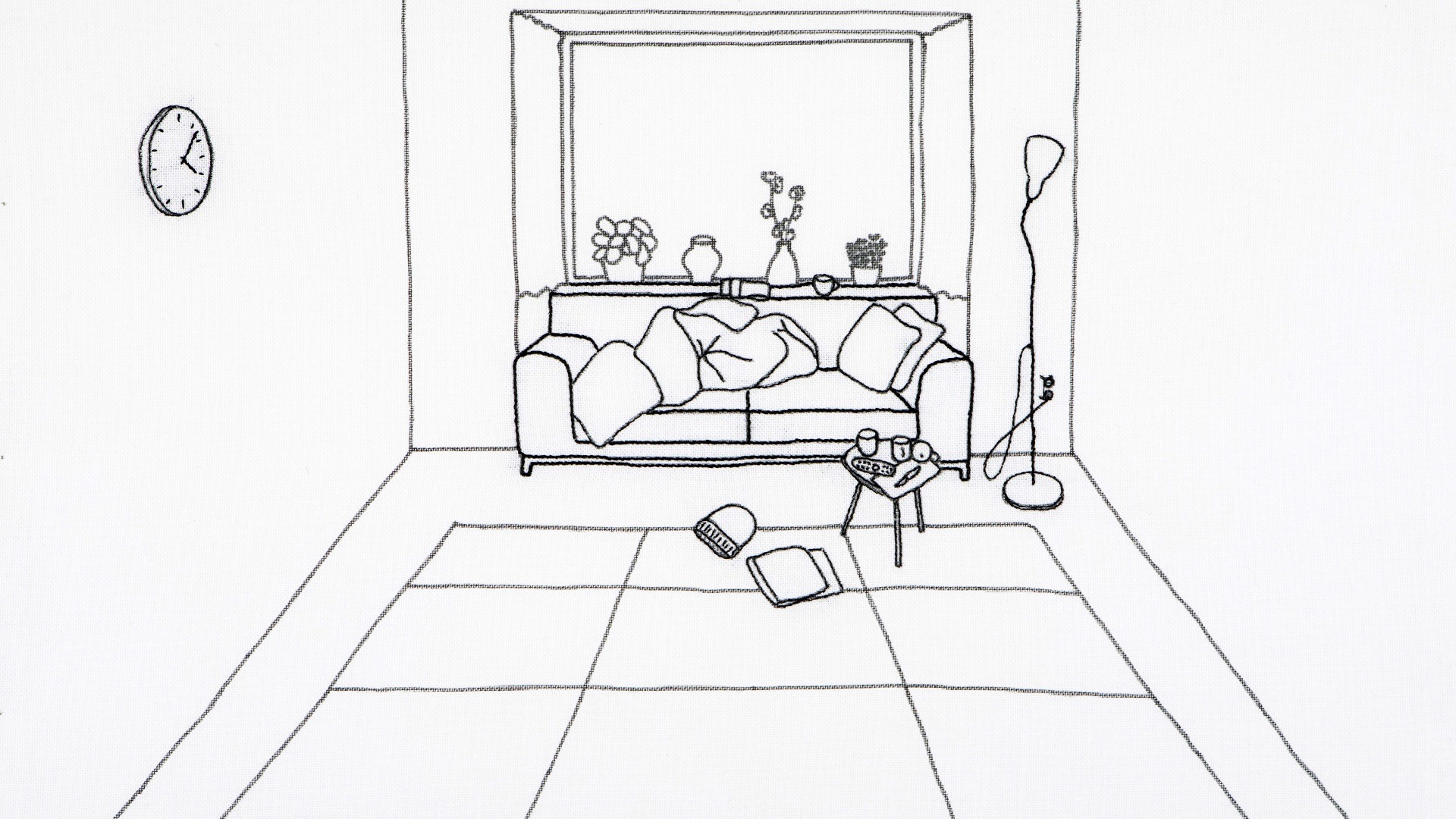

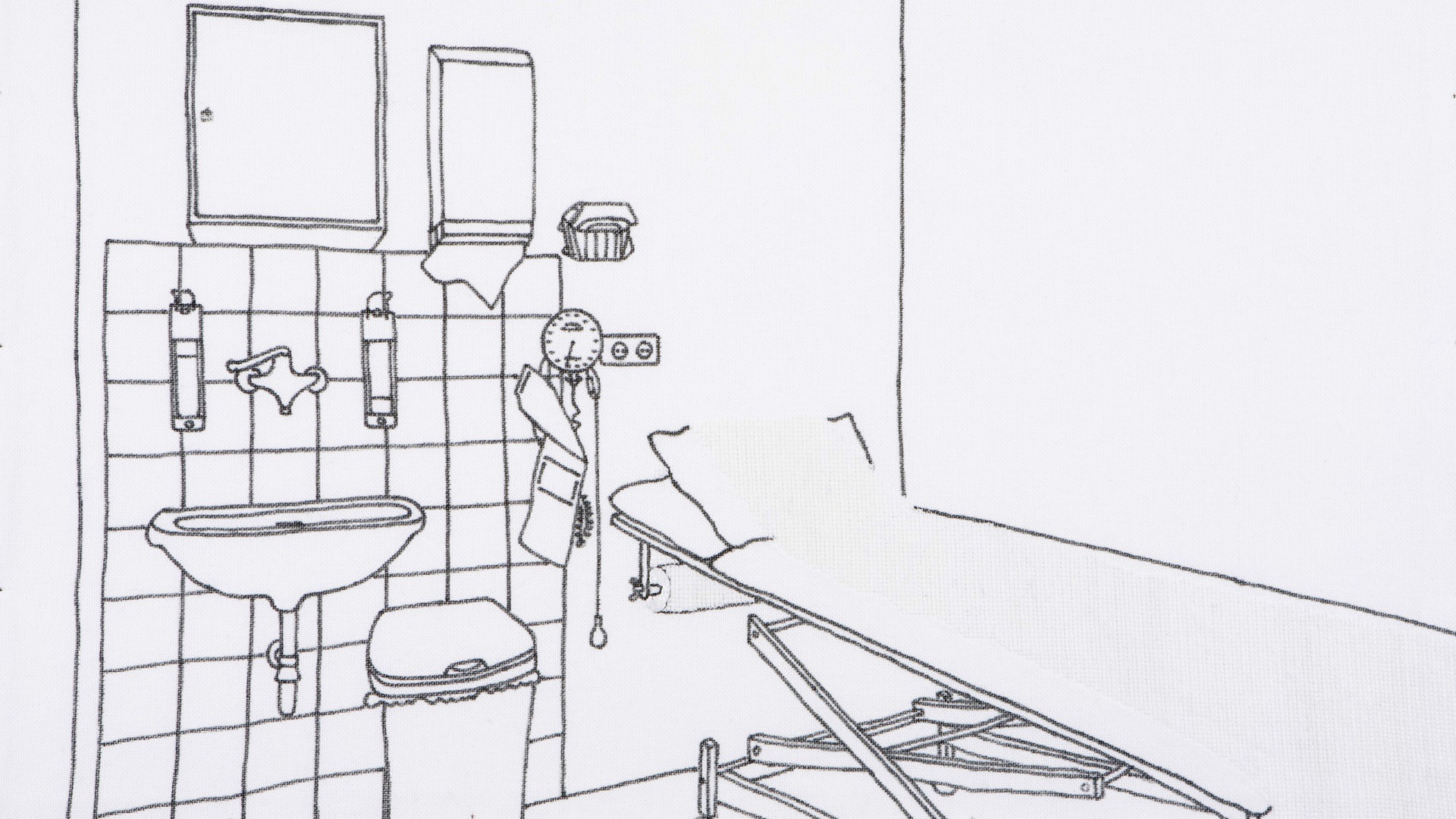

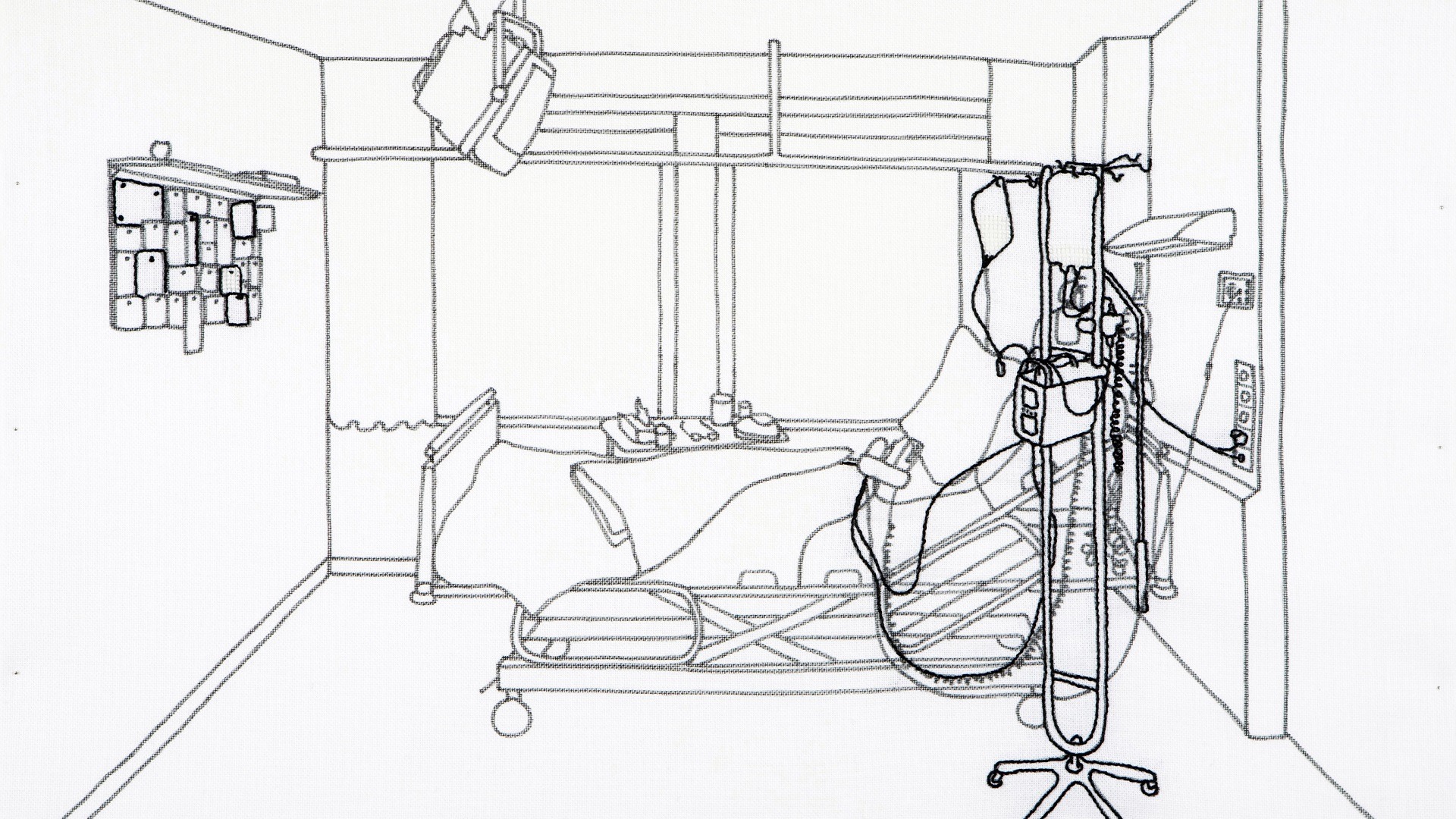

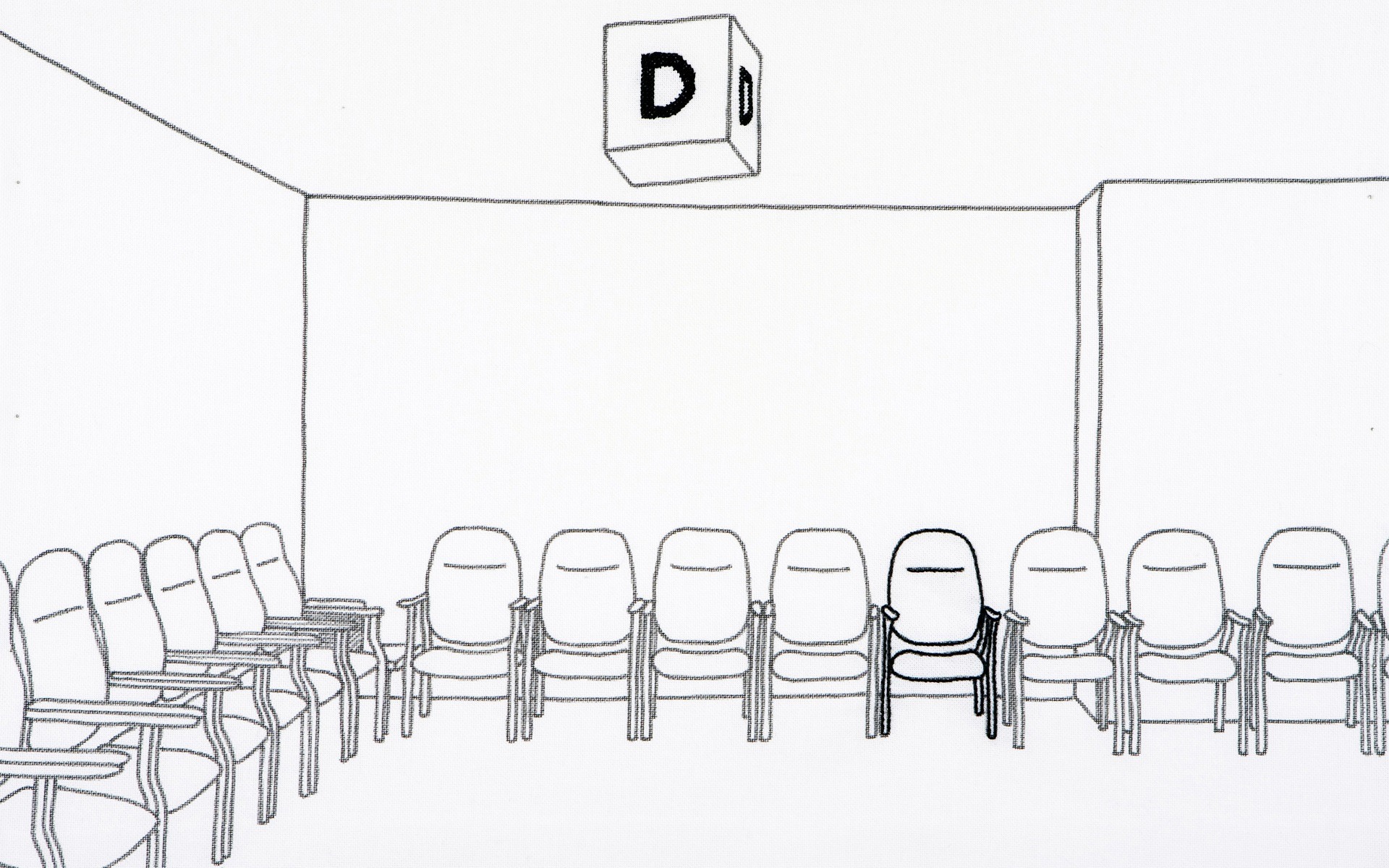

For better or for worse is a collection of five pieces showcasing pivotal times and places across what Sonja calls ‘our cancer rollercoaster’. Though each panel features simple black embroidery on a white linen background, the stories are massively poignant. Especially her depiction of her husband’s knit hat.

‘I wanted the images about being sick to be as clear as possible and to embroider what needed the most attention. Every night when my husband went to bed, he threw his knit hat at the corner of the bed. He was bald from chemotherapy and very thin, so he got cold quickly. In the morning, he’d put the hat right back on. It touched me very deeply, and I knew I had to capture it in stitch.’

Sonja’s attention to detail and purposeful exclusion of people makes her work poetic and recognisable. For example, she chose the sofa and personal items to emphasise how small one’s world becomes when sick. The exam table paper accentuates the importance of a correct diagnosis and treatment plan. The tangle of hoses and pumps in a hospital room demonstrates the severity of treatment.

‘The last work is a waiting room filled with chairs, and one chair stands out. That’s my husband’s chair, as it’s his story. Still, all the other seats show how many other people are sick and dealing with their own stories.’

Sonja’s husband says her work was more about her cancer experience than his. He only served as ‘the occasion’ and seeing events through her eyes was ‘beautiful, powerful and impressive’.

Sonja is based in Nijmegen in The Netherlands. After working as a nurse for years, she attended the Nieuwe Akademie Utrecht (art academy) and graduated five years later. She is most proud of her group exhibition called Kwaadaardig Mooi (Viciously Beautiful) at the Tot Zover Museum (Amsterdam) chronicling their collective cancer journeys.

Website: www.sonjahillen.nl

Facebook: facebook.com/sonja.hillen/

Instagram: @sonja.hillen1

Michelle Ligthart – A woman’s choice

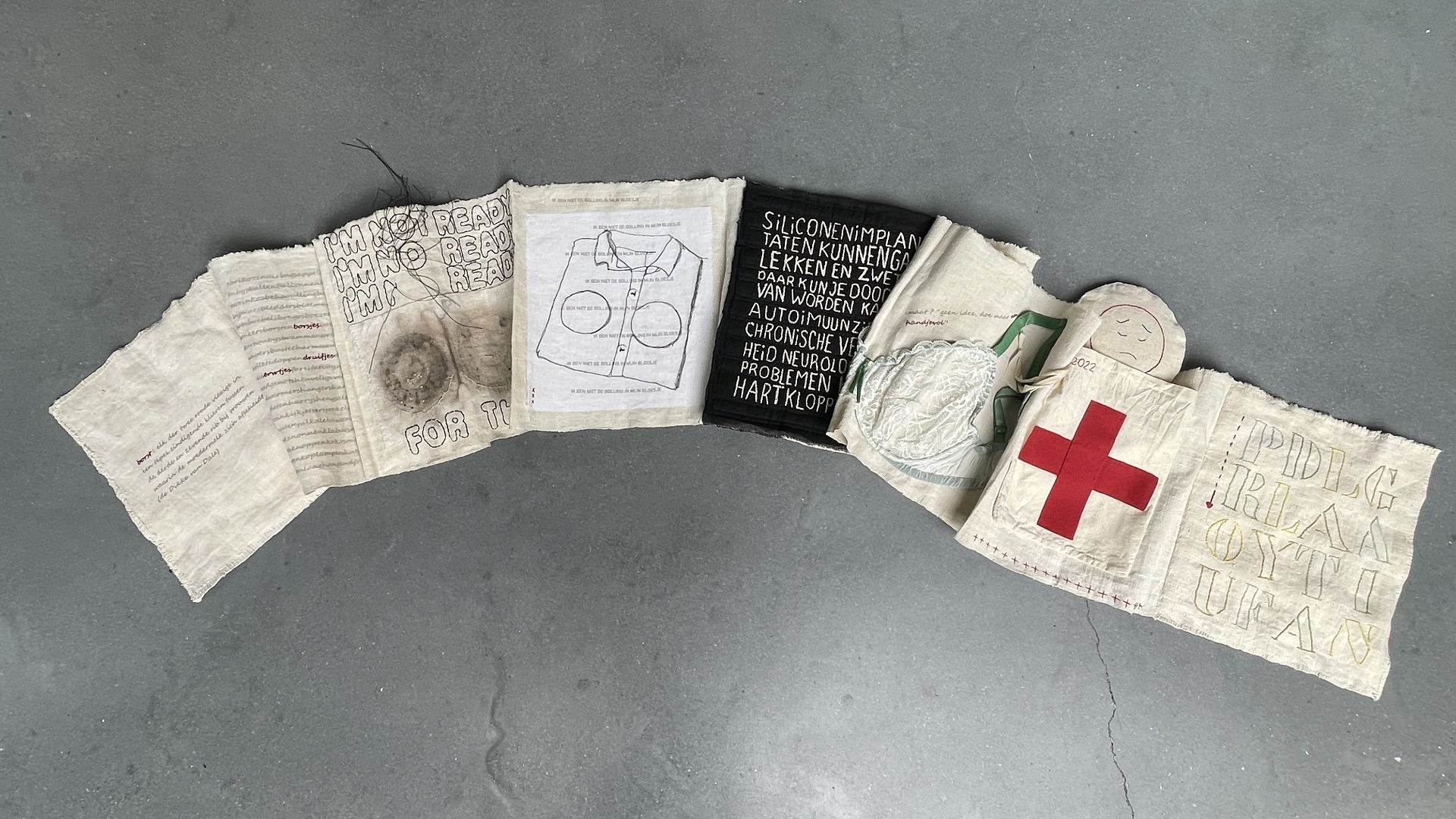

At age 60, Michelle Ligthart made a big decision: to voluntarily have her breast implants removed. She wasn’t ill, but Michelle didn’t want to worry about becoming ill in the future. To be sure, it wasn’t an easy decision. So, she chronicled her physical and emotional journey by creating a textile book called Book of Breasts.

The book’s pages are filled with imagery bearing unique meanings and varied textile art techniques that Michelle learned in TextileArtist.org’s Stitch Club. For example, the book’s cover features a trapunto technique featured in Julie Booth’s workshop. Many breasts in varying sizes are featured, and some have a scar.

‘When I started the project, I was obsessed with breasts. I’d even stare at other women’s breasts. I tried to reflect that obsession across three pages of text. The first page features a neutral definition of breast, and the second and third are filled with every synonym of breast I could find in alphabetical order. Some are funny, and some not so much. I stitched the synonyms for “tiny breasts” in red because that would be me after surgery.’

Michele also used rust printing techniques learned in Alice Fox’s workshop. That page features two breasts with scar stitches reflecting Michelle’s need to prepare herself for the stitches she would have after surgery. She also attached her first bra across two pages.

‘I got my first bra when I was 37, and I’ve treasured it for more than 20 years. My partner gave it to me, after telling the salesperson he needed a bra that fit “a handful”. It has some holes to reflect my saying goodbye to my dear breasts and bras.’

Michelle also included the bag in which she brought the implants home with her. She sewed a red cross onto the storage bag, and then she created stitched covers for the implants themselves that had emoticons on both sides to reflect her mixed emotions about the surgery. The book ends with a colourful page on which she stitched the words ‘proudly flat again’.

A week after her surgery, Michelle hesitantly shared her work in the Stitch Club members’ area. She worried members who were recovering from breast cancer might be hurt, since she wasn’t ill and had chosen to have implants in the first place. But the community’s response was overwhelmingly positive.

‘My decision really affected me, so making the book helped me process my emotions. It wasn’t just something to keep my hands busy. It was an artistic way to create meaning, and the slow stitching helped me reflect on the stages I went through preparing for my operation. I also wanted to create something beautiful out of my sadness.’

Michelle lives part of the year in the Netherlands, and the other part is spent touring South America with her husband in an offroad camper. She started stitching when she joined TextileArtist.org’s Stitch Club, and now enjoys collecting old linens for her work. She plans to create a new textile book in the future.

Haf Weighton – When the artist gets sick

Imagine being commissioned to create a commemorative work for a hospital, only to find yourself hospitalised with an unknown illness during its creation. That’s what happened to Haf Weighton when the Rookwood Hospital in Cardiff, UK, asked her to design a work celebrating its history.

Haf’s symptoms stumped doctors, and ironically, she spent a month in a hospital run by the same trust that runs Rookwood. Eventually, she was diagnosed with a rare form of pneumonia that took over a year’s recovery. She stitched throughout that entire illness journey.

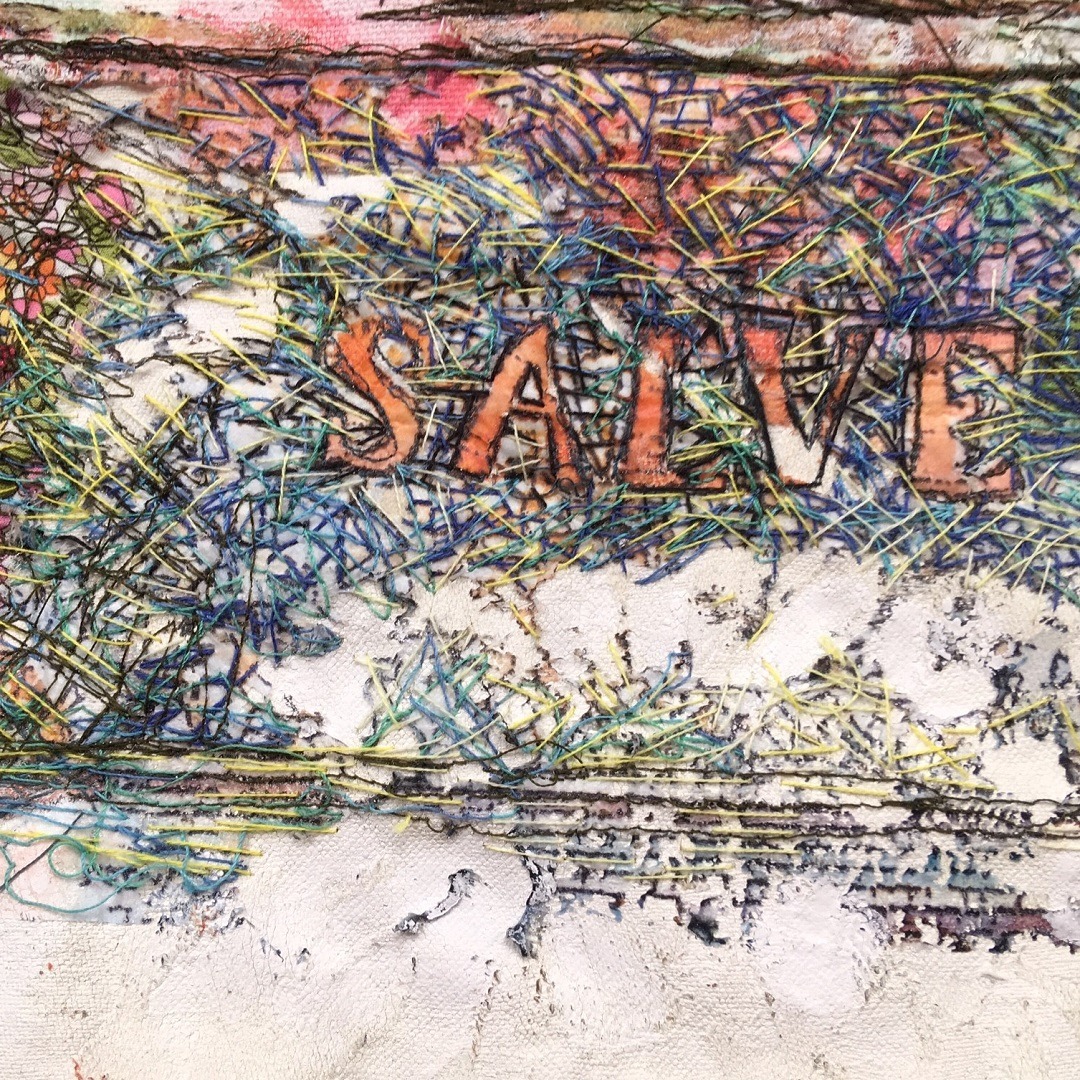

A tiled floor mosaic in Rookwood’s entryway bearing the word ‘Salve’ served as Haf’s starting point. Haf researched its meaning and discovered it roughly translated as ‘heal’ in most languages.

‘I mainly used hand stitch because I was working from my hospital bed. I decided I needed to find a way to heal that didn’t solely rely on modern medicine. This is how I learned the true meaning of “salve” in my illness journey. Stitching kept me strong through it all, and my creativity truly helped me recover.’

The background fabric in Rookwood is recycled cotton sheets. Haf thought sheets were particularly significant for a hospital where patients spend days, months or even years in their beds. Haf first painted the sheets with acrylic paints and then heat transferred her drawings onto the fabric. She then machine-stitched pieces together, followed by detailed hand stitching embellishment.

‘Recovering from an illness isn’t about taking medicine. It’s about finding ways to look after and be kind to yourself. So, for me, “salve” is about stitching. And I literally used that commission to stitch my health back together.’

While Haf beat the odds with pneumonia, she tested positive for Covid in 2022. It was frightening having already battled respiratory issues. But she again turned to making art, including an online daily drawing challenge that challenged her to sketch what she could see from her home.

‘We spent so much time in our homes during the pandemic. So, when I was sick with Covid, I reflected on the comfort of our homes. I used my creativity to help me recover by turning those sketches into stitched pieces. That body of work has now grown into an upcoming solo exhibition called “Cysur” which is the Welsh word for “comfort.”

Haf is a Welsh-speaking artist living in Penarth, South Wales. She has exhibited her work globally, and she also runs workshops for both Cardiff and Vale University Health Boards and the National Museum of Wales at Oasis, a centre for refugees and asylum seekers. Haf is a juried member of the Society for Embroidered Work and The Society for Designer Crafts.

Website: www.hafanhaf.com

Facebook: facebook.com/hafanhaf

Instagram: @hafweightonartist

Linda Langley – Diagnostic layering

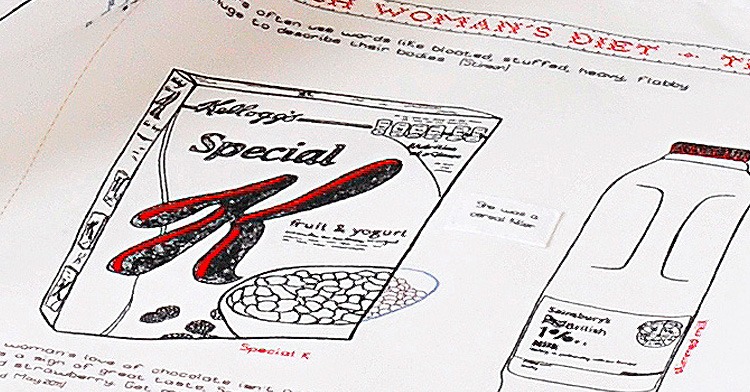

Linda Langley was working as a radiographer when her mother was first diagnosed with breast cancer. Having much experience in mammography, Linda knew her mum faced a serious battle.

Sadly, despite treatment, her mum’s cancer ultimately spread, resulting in bone cancer and brain secondaries. Linda’s mom passed away in 1984.

‘I was very aware of the journey most breast cancer patients take. She was only 67, and while it was a long time ago, I still remember her dearly.’

Linda joined TextileArtist.org’s Stitch Club during the height of Covid. She was enjoying the various workshops, but when she saw artist Jenny McHatton’s presentation, Linda knew she wanted to use Jenny’s creative challenge to memorialise her mum.

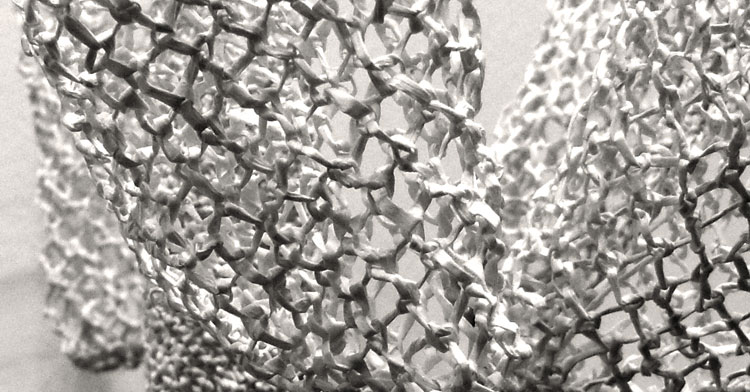

The workshop instructed members to gather a variety of materials and then shared techniques for gathering and twisting those materials in different ways. Boro stitching was then used to help secure the fabrics, as well as add additional surface design. Linda chose a variety of natural fabrics from her collection to twist and stitch. And the base was from an old linen napkin she had received from a Canadian friend.

‘I have learnt to love layers, and therefore, lace and sheers are prominent in my collection. I thought they were especially useful in depicting breast tissue. I knew very little about Boro stitching, so that was a challenge. ’Linda’s piece My Mum’s Breast includes a lateral view of the breast akin to what a mammographer would see. Linda says lateral views are especially important as they visualise the lymph system at the breast axillary area which can sometimes show if cancer cells have spread to other areas. Linda sought to create the breast’s complexity using twisted fabric layers and stitch to recreate its many layers, blood vessels and nerves that go in all directions.

‘I loved making this, especially thinking it could encourage women to have mammograms. And I was thrilled by other members’ positive feedback. I hadn’t worked with textiles for a long time due to life’s challenges. And my education was incomplete due to financial restrictions. Members’ feedback gave me the confidence I needed.’

Linda is retired and resides in Croxley Green, Hertfordshire. She especially enjoys the research aspect of embroidery, as well as detail and texture. Other hobbies include cooking and gardening.

Jane Axell – Stitching to heal

Jane Axell experienced a variety of illnesses throughout her childhood, including recurrent chest infections, psoriasis, and some anxiety and depression. Traditional medical treatments were sought over the years, but none seemed to have lasting effects. So as an adult, Jane turned to natural therapies, including courses in reiki and crystal healing. She also explored Christianity, Buddhism and other healing modalities.

In 2007, Jane started working with The Sanctuary of Healing (Lancashire, UK), which delivers a variety of healing frequencies, such as crystal energy and light and colour frequencies. Her health started to improve dramatically, and she hasn’t had a chest infection since 2009. Other ailments have also healed.

‘I learned how stress plays a major role in illness. Stress hormones create an invisible field of energy that surrounds your body and turns off natural self-repair mechanisms. So, you need something to trigger a relaxation response in your mind so your body can heal itself. For me, one of my main triggers is creating textile art.’

Jane is a member of TextileArtist.org’s Stitch Club where she participates in as many workshops as possible. She also attends a monthly stitching workshop, a monthly felting group and a weekly crafting group.

Soft, red rose started as a contribution to an upcoming exhibit for Jane’s local stitching group. Artists were asked to create a red rose (the emblem of Lancashire) in a hoop for an exhibition at Astley Hall. Shortly after Jane started composing her work, she viewed Jenny McIlhatton’s Stitch Club workshop, which featured folding, rolling, twisting and loosely stitching different fabrics. It was exactly what she had been attempting to do!

‘The techniques gave my work texture, loft and character. I used all kinds of scraps from my fabric stash – from curtain samples to fine cottons and scrims. I love their soft fraying. I also adore silk velvet and used that for the soft folds of the rose. A piece of hand-dyed red silk is in the centre.’

The stem and leaves were created from a piece of printed cotton covered with loop stitches, and red French knots also added texture. In addition to being pleased with the result, Jane said it also boosted her creative confidence.

‘I think by indulging in any kind of creative practice, you can forget your cares, and enter into a sense of wonder and playfulness that can be very healing. Honouring your creativity is your way of bringing love into the world. The secret is to carry that lovely feeling back into your life once your play session is over!’

Jane lives in the picturesque Ribble Valley in Lancashire, UK. She is a writer for TextileArtist.org where she loves interviewing and writing about a wide variety of textile artists. Jane participated in her first exhibition called Colours, Textures and Heritage of Lancashire (2022) with Ribble Creative Stitchers and the Bolton Stitch Group.

Instagram: @jaxtextiles

Comments