The immigrant experience is necessarily challenging: how much does one assimilate while also still maintaining one’s cultural identity?

When Amarjeet K. Nandhra’s family immigrated to the UK from Tanzania, her parents did everything they could to help their children blend into their new setting. They were to adopt Western ways as best possible, including no longer speaking Punjabi at home.

But when Amarjeet was in her 20s, her Indian heritage started calling to her heart. She decided to reclaim her Punjabi language and explore the incredible Indian textile traditions she left behind.

Ultimately, Amarjeet started using modern print techniques and traditional textile methods to express the challenges she faced trying to straddle two cultures. She had grown to love her UK life, but she didn’t want to lose sight of where she came from.

Amarjeet’s practice has led to a larger mission to broaden people’s understanding of traditional Indian textiles. She wants viewers to not only admire their beauty but to also understand the personal and political backdrops each traditional cloth carries.

Aha moment

Amarjeet K. Nandhra: My mother was an incredibly accomplished embroiderer who stitched all our clothes and embroidered household items. But when we came to the UK, she had to work and raise six children, which didn’t allow her any personal time.

Mum never taught me to embroider either, but that was okay, as I was focused on art. I avoided stitching because of its association with domesticity and femininity.

However, whilst studying for an art and design diploma, I felt something was missing. Then a close friend bought me a book about machine embroidery, and that was my ‘aha’ moment. I enrolled in Pam Watts’s machine embroidery course, and I was hooked.

In 1998, I enrolled in a City & Guilds Embroidery Part I class at Harrow Weald College, and I completed Part II in 2001 at Missenden Abbey. I then took an Advanced Textiles Workshop with Gwen Hedley and graduated with distinction in Higher Stitched Textiles Diploma. I also gained First Class Honours in Creative Arts…

“All of that learning helped fill my days and allowed me to navigate some difficult times in my life.”

Amarjeet K. Nandhra, Textile artist

I was able to learn from some big names, including Janet Edmonds, Jan Beaney, Jean Littlejohn and Louise Baldwin.

Later, Gwen Hedley asked me to take over teaching in Advanced Textiles, and I also started teaching for the Higher Stitched Textiles diploma alongside gaining my certificate in further education teaching. It was a very busy time for a recently divorced mother of two young children.

Reconnecting to my heritage

Navigating the world of textile art without guidance and support that mirrored my experiences was challenging. My desire to embrace and connect with my Indian heritage was accompanied by complex emotions and expectations of authenticity.

I also lacked confidence as a young artist, and my work was significantly impacted by receiving conflicting feedback from tutors and event organisers…

Some said my pieces were not ‘Indian enough’, while others felt the colours were too ‘ethnic’.

It wasn’t until later in my creative journey that a renewed passion for the colours, patterns and symbolism associated with traditional Indian textiles began to inform my work. I researched the historical patterns and symbols seen in phulkari, Kantha work, embroidery and mirror work.

That exploration prompted a significant shift in my artistic practice. I’m now excited to explore the vibrant and diverse colour combinations and stitches commonly found in Indian textiles.

Passion for phulkari

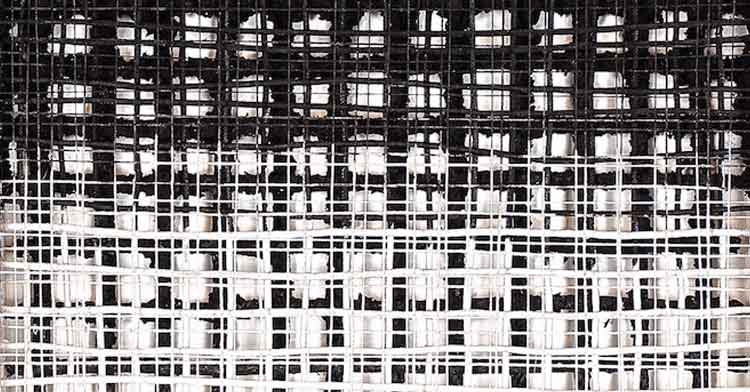

India’s 1947 partition caused one of history’s largest forced migrations. As Pakistan and India gained independence from Britain, a bloody upheaval displaced 10-12 million people, including my ancestors. Communities were fractured and many cultural arts were lost.

In light of that loss, I wanted to reconnect to textiles from my Indian heritage, especially exploring the traditional patterns and symbols featured in phulkaris. Phulkari is an embroidery technique from the Punjab region – ‘Phul’ means ‘flower’ and ‘kari’ means ‘work’.

“In addition to being beautiful, phulkaris were powerful symbols of Punjabi cultural identity.”

Amarjeet K. Nandhra, Textile artist

Maps & patterns

Phulkaris were forms of ancestral maps that documented the daily lives and social relationships of the makers. These textiles became visual diaries packed with symbolism and significance.

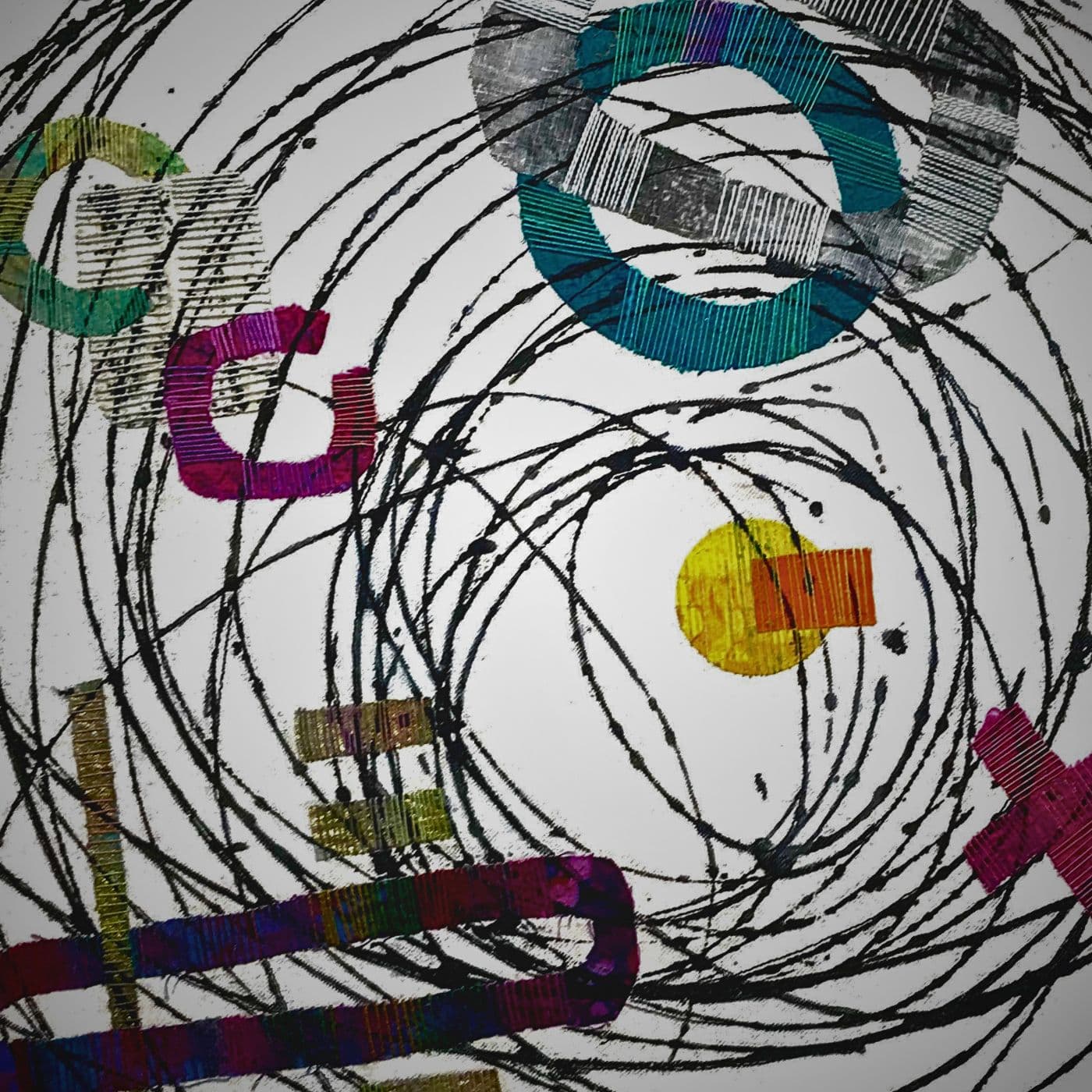

The patterns of phulkaris have become my palette for sharing my own migration story. One of the traditional motifs I use is the four-faced Kanchan design, featuring triple V-shaped lines repeated in four directions. I also use stylized Mirchi (chilli) rectangle shapes repeated in a cross form. And I use small multicoloured lozenges that mimic Meenakari enamel works.

For my more contemporary responses, I create my own stitch motifs. For example, in Mapping, I used diamond shapes and long blocks to represent fences and borders.

Meaning and memory

Indian textiles have a captivating allure that can sometimes lead to a superficial understanding of their significance. So, I encourage viewers to look beyond the beautiful and intricate embroideries and recognise their vital roles in carrying meaning and memory.

“I seek to explore and promote Indian textiles in a broader context.”

Amarjeet K. Nandhra, Textile artist

While I’m fascinated with the decorative qualities of Indian textiles, I believe it’s equally important to consider how textiles tell stories about their creators, the history they embody and the memories they hold.

Still, narrative and aesthetic qualities are equally important to my practice. I want to make work that is beautiful as well as thought provoking. Work that celebrates tradition while also creating a relevant and contemporary dialogue.

Thought books

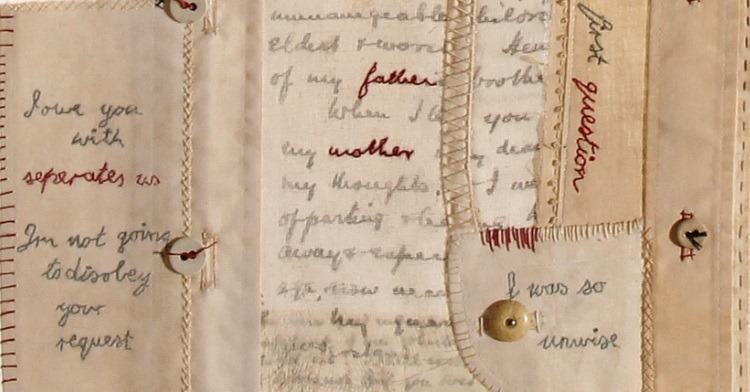

I start a project by exploring my thoughts in a book where I draw, write and doodle anything to help generate ideas. I call them ‘thought books’ instead of sketchbooks.

Once I have an idea, I formulate a plan. I begin by drawing out a rough sketch of the piece and decide how to build the layers of print. While I’m careful with my planning, I’m also mindful that the work will evolve and I will adjust accordingly.

I also work with other sketchbooks to experiment with different materials and processes, explore mark making and colour relationships, and build up layers with text and collage. These books don’t always have an end goal.

Printing the unexpected

Print has always played a big role in my art since my first job at a print cooperative. We produced banners for trade unions and many social causes. I was struck by the bold designs and repetition of images that could carry a message and communicate a story.

Building up layers is the foundation of my practice. And there is something magical about revealing the print and discovering the unexpected.

But I wasn’t always comfortable with the unexpected. At the print co-op, everything had to be precise and accurate. That led to my work becoming rather dry and boring.

As I became more confident with the processes, I overcame the fear I might spoil something. I realised building up layers was far more interesting and adding more to a work made it look better. I had to practise my practice.

“I love the physicality of printing, the smell of the inks and the sound of ink being spread out using a roller.”

Amarjeet K. Nandhra, Textile artist

Pigments & dyes

I have used Selectasine fabric binder and eco pigment. And I’ve recently started to explore traditional Indian textile natural dyes such as madder, cutch and indigo.

When I want to remove colour in my print, I use a ready-to-use printing paste that allows me to take away areas of colour from natural fabrics such as cotton, linen, silk and wool.

I’m excited to teach several experimental mono printing approaches in my Stitch Club workshop, where members produce a variety of layered prints using colour, mark making, pattern and texture. These printed fabrics will then be collaged together and embellished with stitch.

Stitch Club members will use the process to create a series of works that are related but also have interesting differences that will engage viewers.

Subjective materials

My fabric choices really depend on the project. I like experimenting with different natural fabrics, as I feel it’s part of the serendipitous nature of printmaking. I don’t like working with synthetic fabrics.

For larger printed and stitched works, I tend to use 7.5-ounce cotton duck or cotton canvas from Whaleys or Wolfin Textiles. For other projects, I might use linen, cotton lawn or organdy.

Most fabrics work well when screen printing as long as they’re pinned to create tension. But for mono printing or collagraphy, fabrics need a smooth surface.

When it comes to hand stitching, I use a combination of silk, cotton perlé and stranded cotton threads. I tend to use running stitch, surface pattern darning and straight stitch. The stitches I choose depend on the project and my response to the subject.

The complexity of identity

My Other Words is a personal reflection on the dynamics of straddling two cultures and navigating the complex notion of identity. When we arrived in the UK, my father was determined we would ‘fit in’, so we were told not to speak Punjabi at home.

“Growing up and being ‘othered’ impacted my sense of pride for my heritage – keeping invisible was the goal.”

Amarjeet K. Nandhra, Textile artist

In my 20s, I decided to speak and embrace Punjabi, and this work connects to that shift.

I used Punjabi text as the foundation of this piece to reflect that reconnection. The text was printed, then erased and then overprinted. The text is complemented by fabric shapes and patterns typically used in phulkari, then emphasised with kantha stitch.

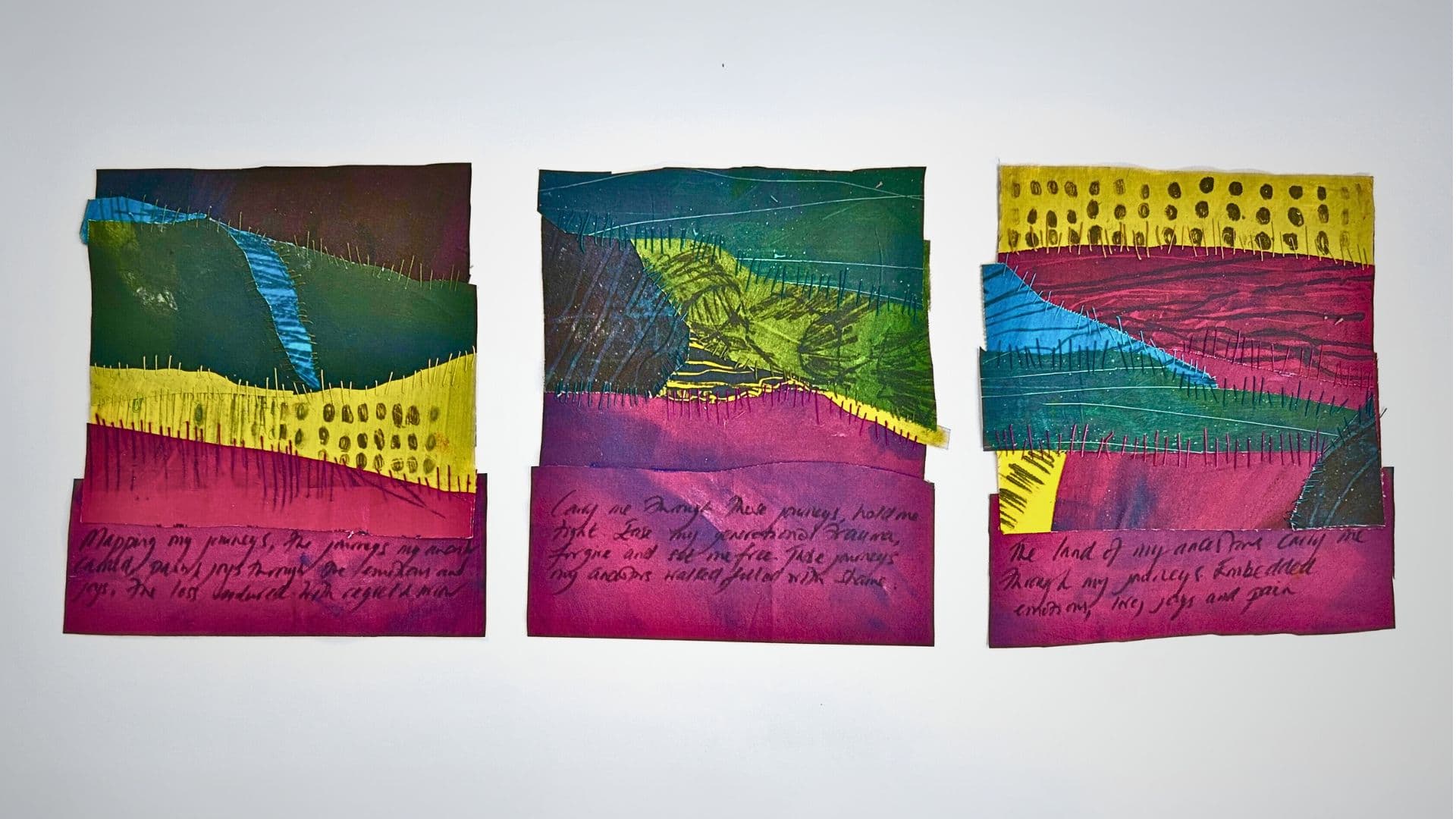

Mapping place and space

Mapping Place and Space uses the concept of phulkari to map and document the maker’s activities. I recorded my movement through urban and natural landscapes.

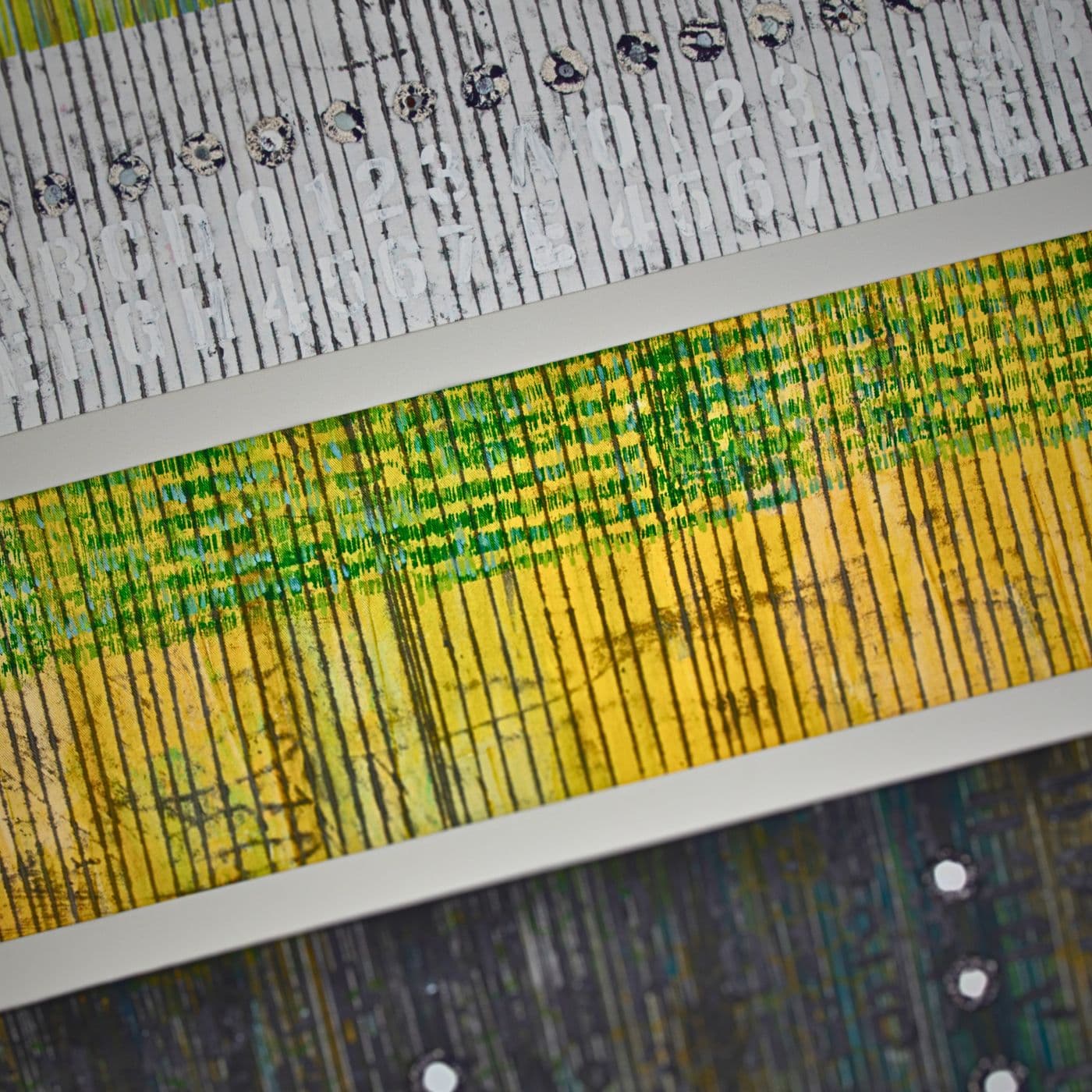

The background was painted with fabric paint using binder and pigment. This freed me to mix my own colours with reference to my sketchbooks. I then overprinted with mono printing and additional details were added using acrylic markers.

The diamond shapes and bars were a nod to the traditional phulkari patterns and stitches. I originally planned to create one large piece, but I liked the idea of being able to change the sequence and configuration.

I also played around with the idea it could be folded like a paper map.

An immigrant’s story

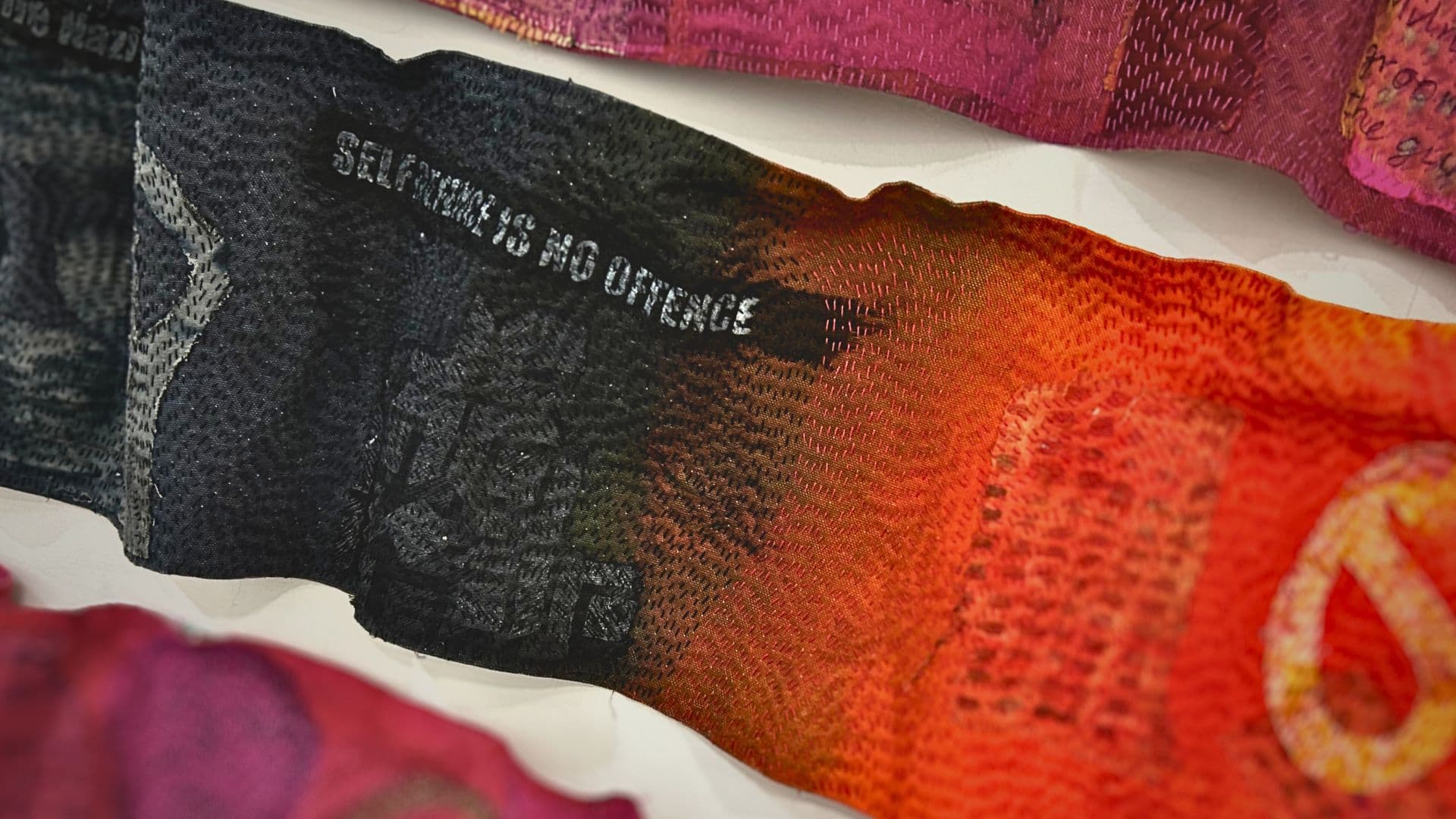

Five Decades is the story of growing up in the UK after moving as a child from Tanzania, Africa. Each scroll represents a decade of my life in England.

It documents the trials and tribulations of living as an immigrant and how an unwelcoming country eventually became home.

Each fabric strip is dyed, painted and printed with carefully selected colours representing each decade’s theme. A range of printing methods, collagraphs, mono and screen printing are used to capture the mix of my painful and joyous memories across those 50 years.

“Every strip contains an image of my mother to represent the substantial influence she had on my life – our strong and special bond has influenced both my life and artistic journey.”

Amarjeet K. Nandhra, Textile artist

Conversations and stories are captured, with the final layer of each scroll binding memories together through kantha stitch.

Various text is featured across the strips. For example, there’s an image of a sticker with the words ‘Fight racism’. I had printed those vinyl stickers when working at a print collective in the 80s and wore them when I attended demonstrations.

The phrase ‘Self Defence is No Offence’ comes from when the National Front decided to hold a meeting in Southall’s town hall. Thousands, mostly Asians, took to the streets in protest against the far right and police brutality.

‘Finding my voice’ represents me finally being seen and finding my visual language. It also expresses the joy textiles have brought to my life.

Comments