Andrea Mindel’s life has been both gifted and fortunate, and – some might say – downright disastrous at times. Since her early life, surrounded and taught by successful artists and makers across several countries, she has experienced homelessness, single motherhood, racism, domestic violence, legal difficulties and ill health.

Yet, all the while, Andrea has relentlessly pursued her love of needlework – at one time ‘crocheting her way through the trauma’. While homeless in her mid fifties she embroidered works that were later exhibited in a Paris gallery. More recently, her dedication to stitch has paid dividends as she has won Arts Council funding and a DASH public art commission that will ensure her work is recognised and will enable her to further her education with the Royal School of Needlework.

Andrea is a contemporary textile and multi-disciplinary artist based in the UK. Her practice addresses themes of social injustice, grief and mourning within the context of climate crisis, illness, disease and genocide, and she uses her work to advocate for the LGBTQIA+ community and other under-represented voices.

She continues to embroider with conscience – one stitch at a time – creating materiality through the repetitive motion of stitch. Her work pays tribute, memorialising and making beautiful things from difficult narratives. And as she does so, she is finding her authenticity in the world.

World of learning

TextileArtist.org: What initially attracted you to textiles as a medium? How was your imagination captured?

Andrea Mindel: I grew up in a small mining town in South Africa during the apartheid regime. When my maternal grandmother died young, we moved into my grandfather’s house. There, I was surrounded by the functional textiles she had created in her lifetime – I couldn’t help being engaged by the burgundy wool tapestry rose seat covers we sat on at the dinner table, and the many tablecloths she embroidered.

Constructed textiles and the complexity and engineering of stitch grabbed my attention right from being a child. I remember the pleats in a favourite childhood skirt, the smocked bodice of another dress, the broderie anglaise, the cut-away embroidery, the beading. And so, from a young age, I stitched, crocheted and knitted.

What or who were your early influences and how has your life/upbringing influenced your work?

My Swazi nanny, Agnes Ngwenya, helped me with school knitting and sewing projects. My mother knitted to perfection, and my uncle, Ian Weinberg, was a dress designer in the city. We used to visit his studio in Johannesburg in the 1970s. I remember watching the African ladies hunched over a table as they sat intricately beading. Uncle Ian painted on silk, beaded and manipulated fabric and created a wardrobe worthy of a movie star for my mom. My paternal grandmother, Bessie Mindel, was a seamstress and workshop supervisor in the East London sweatshops between the two world wars, and my grandfather, Harry, was a milliner.

In the 80s and 90s, I learnt to silkscreen on fabric whilst hanging out with South African artist Steven Cohen. His African mother and muse, the artist Nomsa, taught me African beading techniques whilst mending a broken heart (or two).

My current foray into embroidery came out of my own experiences: as a marginalised single parent of a black child, domestic violence exacerbated by racism (systemic and personal), the downright injustices of the family court system, of being picked on for being different, and to top it all, being slam-dunked by an early menopause and ill-health.

I stopped trying to be normal and started experimenting with making things to preserve my sanity.

What was your route to becoming an artist?

It was in the biology laboratory when in the first year of a medicine degree when I was drawing the frog, rat and catfish that we were tasked to dissect, that I realised how much I enjoyed drawing. I never finished my medical degree: I had been ill as a child and spent some years in hospital with a kidney disease, and I realised I didn’t want to spend my youth in medical books.

So I moved on and completed a BA in English and Psychology and then studied architecture for three years. My first year was in South Africa, and then I emigrated to London where I continued studying for a couple of years on a day release programme – four days working in an architectural office and one day a week at university. I didn’t complete that degree, as I married and moved to Switzerland until my divorce a few years later when I returned to London. But I developed a penchant for technical drawing and, to this day, I carry rotring style black Indian ink pens with me wherever I go.

I went to adult education classes and night school wherever I found myself in the world and have always felt the need to be making. I learnt etching at the ETH in Zurich, pottery with Kim Sacks in Johannesburg, silkscreen at Chelsea School of Art summer school, and formed and stained glass at a polytechnic in West London.

When I returned to London I worked for seven years in animation. I set up my own business, a telecoms start-up at the beginning of the internet boom. My business partner was the father of my son, and, because we weren’t married, the family court system let me down and I lost everything. I turned my back on commerce and capitalism in 2010 and started to silkscreen images I photographed onto fabric. I also made soft furnishings which I sold to local high street shops and on markets.

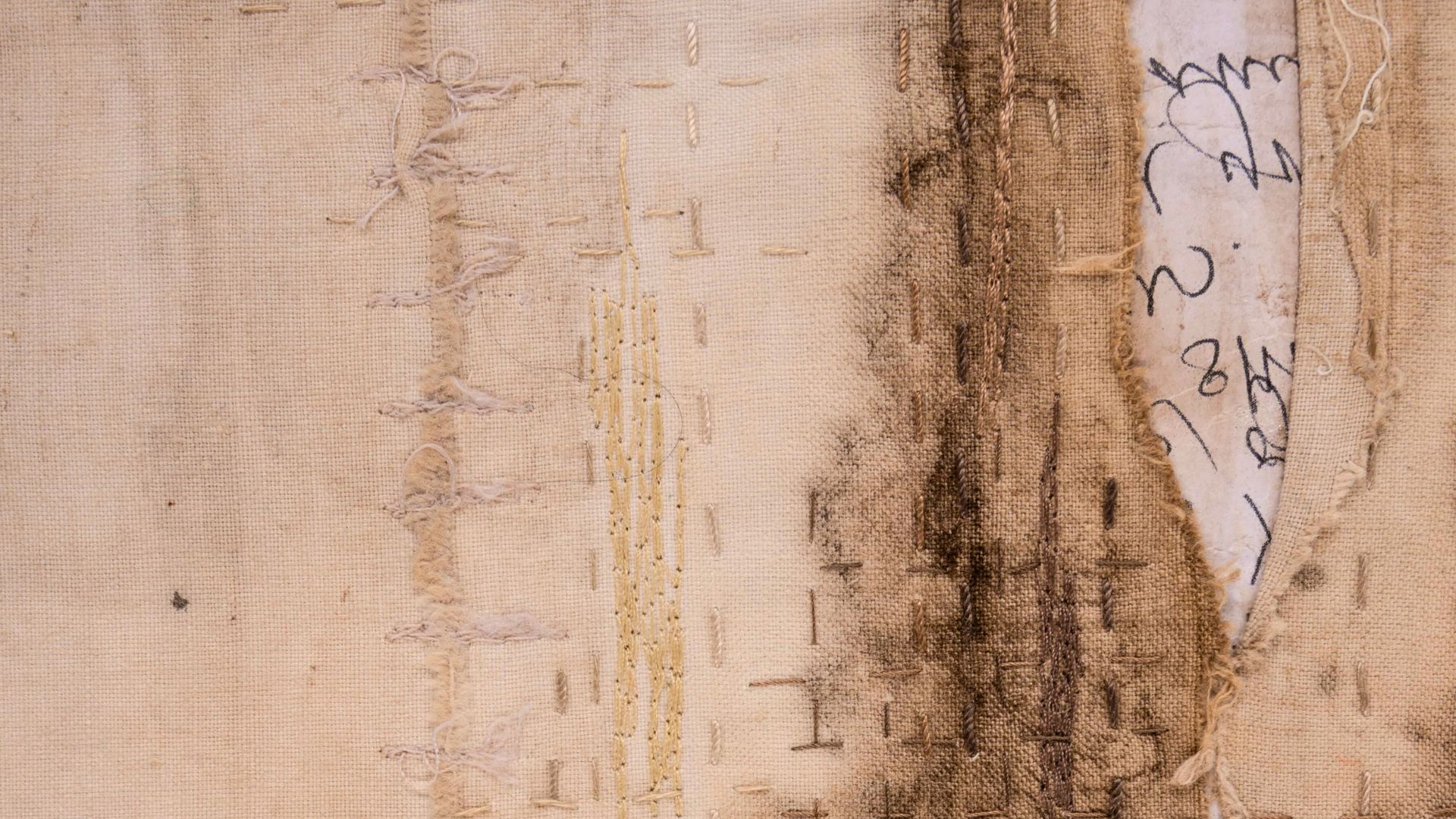

In 2014 I started to stitch on paper. I was looking for ways to elevate the domestic to fine art. It wasn’t until 2016, when in my mid-fifties and homeless, that I started to crochet a non-functional object using algorithmic patterns. In my backpack, I carried a cone of my grandmother’s 1930s Coats vintage raw cotton that had been to Africa and back, and I crocheted my way through the trauma.

I saw that if I removed functionality and refrained from decorating the surface of domestic things in expected ways, I could cross over the Rubicon from “women’s work” and craft into fine art.

A friend saw the works I made on public transport and sitting in cafes with nowhere to go and asked me to exhibit them at the Mannerheim Gallery in Paris in May 2017. I realised then that there was a future for me centred around the engineering and mechanics of stitch.

It was whilst finishing a piece for that exhibition that I discovered the Royal School of Needlework. I had found a pair of white ceremonial leather gloves for £1 in a local charity shop and started to hand embroider one of them. I was having trouble working out how to secure my thread into the leather, and how to finish off the thread. In the end, I left the needles and threads hanging from the glove, which contributed to the narrative, and worked visually.

In 2019 I joined the Royal School of Needlework Certificate in Technical Hand Embroidery, and finally learned the correct ways of starting and finishing my thread. I was very intimidated by the RSN, and it took me a year to complete the first module in Jacobean crewelwork. I struggled to fit in, it was a strain financially, and physically my health was starting to decline. My first module Jacobean crewel work piece, One For Sorrow, was never handed in because it was selected for the Hastings Open 2020 exhibition at the Hastings Museum and Art Gallery, and then the pandemic took over. By the time One For Sorrow returned home from being on exhibition I had moved towards a self-directed programme of learning. I continue to study with the RSN online.

After the surprise of having my crewel work piece selected for the Hastings Open 2020, I joined Outside In, an arts disability charity where I have an online gallery of my work. Later in 2020 I was awarded The Arts Society Southdowns and Outside-In Dr Andrew Edney bursary which paid for some of my RSN tuition days. I became an ambassador for Outside In.

In 2021 I received an Arts Council Develop Your Creative Practice funding which has allowed me to pay for more tuition and to buy equipment and materials. I have also had the support of an access worker which has taken a lot of stress out of the process and allowed me to focus on making work.

In December 2021 I was awarded my first public commission from DASH, a disability-led arts organisation designed to highlight the discrimination disabled artists encounter. WAIWAV – or We Are Invisible; We are Visible – will take place at the Towner Gallery in Eastbourne in July 2022. I will be taking my embroidery trestles into the public domain where I will create an intervention using digital projection and capture as I embroider my hair using goldwork techniques. This work is about collective grief and remembrance, particularly referencing those who have died from Covid the world over, and pays homage to the Victorian traditions of hair jewellery to remember those we have loved and lost.

Receiving the Arts Council DYCP award was a sign of acknowledgement that I am a bona fide artist.

Needlework and expression

Tell us about your process from conception to creation

I tend to get fired up by social issues to the point where I feel I am going to explode. Needlework has become my way of unpicking what bothers me and trying to work out what, if anything, I can do about it without hurting myself or anyone else!

I always carry notebooks and pen and record ideas and references. I keep a sketchbook for each new piece I make so that I can draw and record the thoughts I have that relate to it.

I have started to use long titles for my embroidered works. This mechanism reflects the time it takes me to make the work and shares something of the mental topography and layering of thoughts I experience as I work. The long titles add to the physical and material capture of time inherent in the work and are my way of creating a value system outside of money – one that reflects time, skill, and the intellect beyond the materiality: one that removes needlework from the domestic and sets it alongside fine art. This is my way of positioning my work in the world, of imparting gravitas and relevance beyond the maligned moniker of women’s work.

Traditional needlework, as taught by the RSN, requires a great deal of preparation, with most of the creativity happening before you pierce your fabric with your first stitch. Embroidery can become a bit like painting by numbers or colouring in, so I look for ways to honour the process as much as the outcome.

I am still finding my voice and my process. The Arts Council grant affords me the luxury of creating series of works: I can experiment and build on each iteration of a particular technique, as well as explore ways of combining them.

My process is also moving from isolation towards exposure and collaboration as I prepare my first museum/gallery intervention that revolves around bringing the tools of my trade into the public arena.

Tell us a bit about your chosen techniques and how you use them

I currently use crewelwork for pieces that relate graphically to the Holocaust, man’s damage of our environment, and illness – this is my personal development of the original Jacobean crewelwork motif of the tree of life.

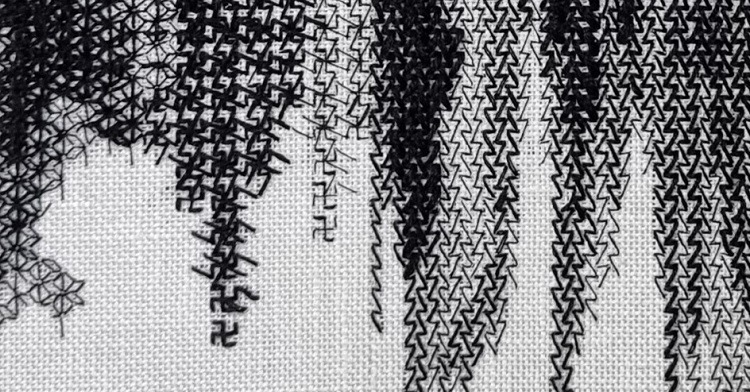

I use blackwork to combine abstract geometries representing topographical layering of thought. Long titles root these pieces in my personal iconography and reflect the temporality of their creation. Words help move the work from individual grief to shared culpability and collective grief with measure, one small stitch at a time.

I use couture beading techniques and stumpwork for pieces relating to Hitler’s system of classification of prisoners during the Second World War.

I use goldwork and silkscreen for work about the Holocaust and concentration camps.

I tend to steer away from traditional depiction of flora and fauna which characterises much of embroidery art, as for me it entrenches the notion of women’s work serving the patriarchy.

I am still learning the essential embroidery techniques. I would like to learn and experiment with three-dimensional stumpwork, applique, silk shading and canvas work. The RSN is a heritage craft resource where one can learn the tried and tested ways of doing things. This gives me confidence that the work I make isn’t going to unravel or become unstuck in 20 years.

I am fascinated by the reverse side or the back of work, particularly blackwork. Traditional mounting means that you lose the beauty of the reverse side. I am reminded of 16th-century triptychs which would have calm religious iconography on the front panels, and paintings of debauchery and violence on the reverse. Having a front side and a back side is something so very unique to needlework and, in keeping with my social values, I like to acknowledge both.

Needlework lends itself to working with text. It is asemic text which grabs my attention. Our brains are conditioned to interpret and make sense of things, yet asemic text perplexes and confuses as it alludes to meaning that is not obvious. It is visually and theoretically satisfying.

I classify myself as a multimedia artist with a focus on needlework. This gives me the freedom to combine techniques in unexpected ways and to never stop learning.

My instinct is to shy away from becoming known for or being really good at one thing, or from being pigeonholed which seems to be the winning formula for having a large social media following.

I’m not interested in breaking things down into palatable chunks. Life is messy.

What currently inspires you?

Currently, I am inspired by the writings of Hannah Arendt, the political philosopher and Holocaust survivor. I am inspired by the non-binary, queer lesbian, trans-creativity of Claude Cahun’s self-portraits, and her resistance during the Nazi occupation of Jersey.

I am inspired by stories of refugees, living in internment camps whilst we carry on as if they don’t exist. There are acts of genocide in our day and age and, whilst we may feel sad and upset, we carry on with our lives, not caring enough to do anything.

Having grown up during apartheid, and as the mother of a black man, I am inspired by the Decolonise movements and Black Lives Matter which call out white privilege for what it is.

Embroidery has become my means of expression. I am inspired by abstract geometry and how abstraction traverses the real with the imagined, what has been, what is left of what has been, all the while hinting at what will be.

I am inspired by collaborating with other artists, and especially young artists, across different media.

I am inspired to make beautiful things from difficult narratives as a way of paying tribute, memorialising, and finding my authenticity in a world in which I feel lost and helpless.

Embroidery as narrative

Tell us about a piece of your work that holds particularly fond memories and why?

All my work is rooted in pain and injustice, so the phrasing of this question doesn’t work for me.

Jacobean crewelwork highlighted the exotic and the new which came our way because of imperialism in the 17th century. The tree of life is a primary motif of this traditional embroidery technique. My work One for Sorrow hints at man’s excesses, at man’s abuse of our planet over the past 400 years: a vibrant, living branch intertwines with one that is petrified, representing the cycle of life and death.

In every crewelwork artwork I make you will find a crow. The corvidae family of birds have become central to my personal iconography, my expression of my Jewish identity, and my sense of being an outsider. I came to crows via Auschwitz survivor, chemist and author, Primo Levi who wrote about the “corvi del crematorio” when referring to the Sonderkommandos set up by the Nazis to administer their particular brand of evil.

This is the piece that was exhibited at the Hastings Museum and Art Gallery, Hastings Open 2020, and was shortlisted for The Mother prize. Although due to the pandemic, I didn’t ever get to submit it for my RSN Certificate, this work gave me the confidence to apply for bursaries and grants to continue learning traditional embroidery techniques, and to continue to find ways of expressing myself.

Comments