After completing her Masters in textile at the Bergen Art Academy, Åse has established her own art studio and participated in exhibitions, both in Norway and abroad. In 1992 she received The Craft Prize from The Relief Fund for Visual Artists.

Some of Åse’s works have been purchased by Norway’s largest museums, among others, The National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design. Her works have been used to decorate various buildings and offices including a permanent installation at the Norwegian Embassy in Kathmandu, Nepal.

In this interview, Åse tells us how the Norwegian surroundings of her childhood influenced her primary creations. We learn about the techniques and processes she’s developed along the way and how making mistakes can be a blessing in disguise.

Cultivating simplicity

TextileArtist.org: What initially attracted you to textiles as a medium?

Åse Ljones: I`ve always been engaged with the ordinary, everyday objects. The things we each have close relationships with, and I use that as a theme in my art.

The everyday objects are connected to women. To their social and cultural position, and to their work in society. Textile work is often associated with women’s work. We surround ourselves with textiles from our birth until death. We use textiles as useful and necessary items to decorate our bodies and homes, and even our animals and homesteads, tent. The primary role of textiles has always been protection.

And, more specifically, how was your imagination captured by embroidery?

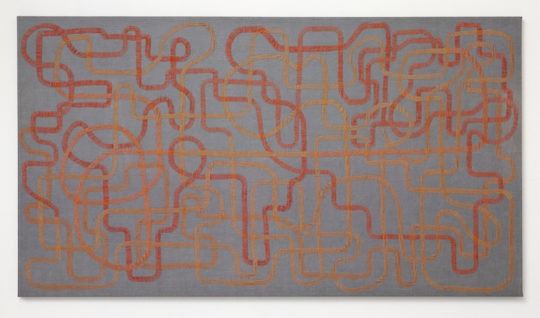

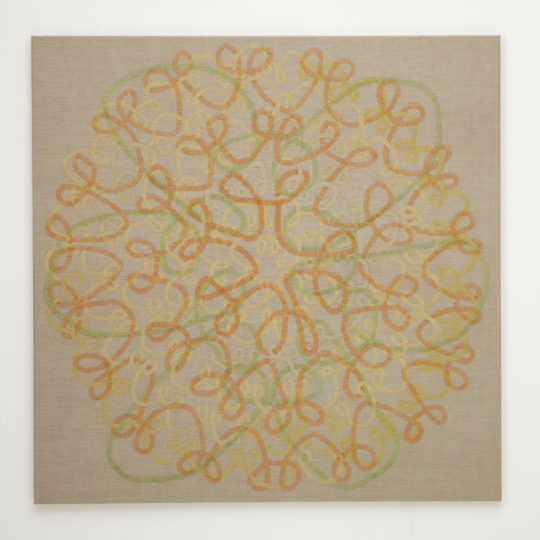

To embroider by hand takes time. It is a slow process that gives room for silence. I seek silence. In silence, I retrieve memories and find new paths forward. In all my work as an artist I have eliminated the extraneous. I’ve cultivated simplicity to approach the core of myself, in myself, with fewer measures. For me the sewing needle is like the pencil is to the author; with it, I can create pictures and tell stories.

What or who were your early influences and how has your upbringing influenced your work?

Having grown up on a small rural farm that was inaccessible by road, where the sea and nature were close by and a necessary element; has meant very much to me and my art. When you grow up so near to nature, you become a part of nature – inner and outer, there are no obvious borders. In these relationships and to the few people around one, it was necessary to be a part of and create, too.

I was surrounded by craftsmanship. With a mother and grandmother who were busy doing (preoccupied with) needlework and a father who was a boat builder, busy with preservation and conservation. “Hardangersaum”, which is a special form of needlework from my district, I learned from my grandmother who had a lot of time for me.

These conditions of adolescence planted a seed to create and pass on that heritage. Through learning via growth to own person competency. The toiling, working people, those who hold forth on their own, who usually lived by themselves in the rural district, they further the silent knowledge through work, and this is how it is passed on further to the next generation. These people, I still admire.

A voice in society

What was your route to becoming an artist?

The road to being an artist was long and winding and difficult. I had always heard at home that I had to get myself a job that I could live from – earn money. I grew up in limited circumstances but inside me lay the need to create. To be a voice in the society. First I took agronomy, and then activity coaching educations before I started art education in 1983.

Tell us a bit about your chosen techniques.

Choosing embroidery as a technique has grown over time. During my studies, I worked with fish skin where I sewed together the fish skins into large two and three-dimensional works. Seams became more and more important; from being simply necessary to moving toward creating new expressions within the works.

How do you use these techniques in conjunction with stitch?

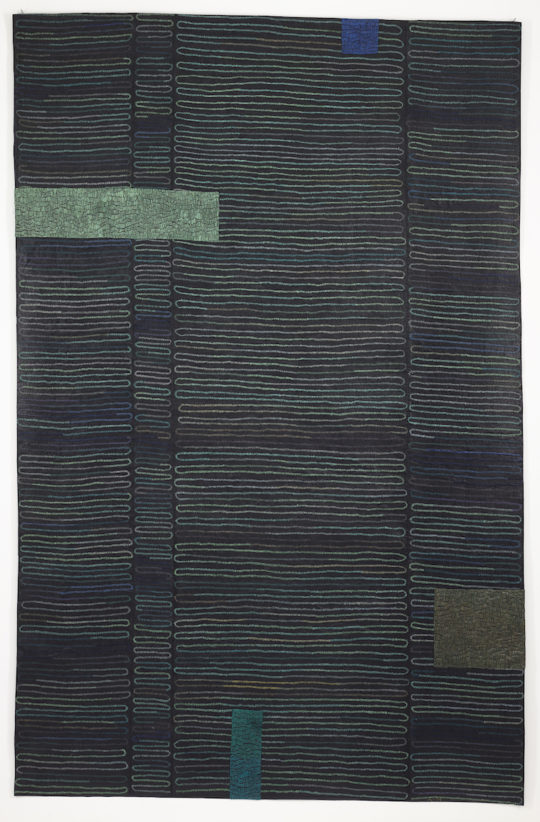

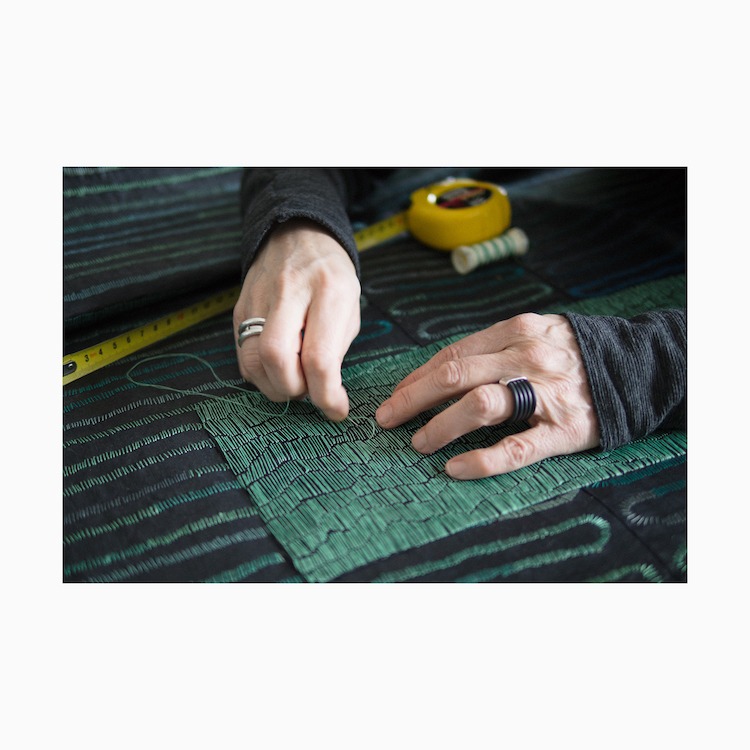

Today I embroider everything by hand. But in the smaller pieces – pictures: that I stretch onto frames, I paint the canvas behind with acrylic paints. When I use the technique primhol (prime hole) from the “Hardangersaum” and the canvas behind is painted – the background colour is visible through the embroidery.

The format is often monumental. The pattern in the larger unframed hangings varies between being organic or built up more geometrically. Most of the works have traditional rectangular or square forms. Even though the visual expression varies, there is not such a great variation on the technique used.

Untraditional embroidery

How would you describe your work and where do you think it fits within the sphere of contemporary art?

Perhaps I am a contemporary artist. Earlier I have been described as a minimalist. Something that has changed over time but something I also return to. In my works the handicraft and the artistic expression go hand-in-hand. My work is the result of my personal experiences but also from the impulses of the flow of society.

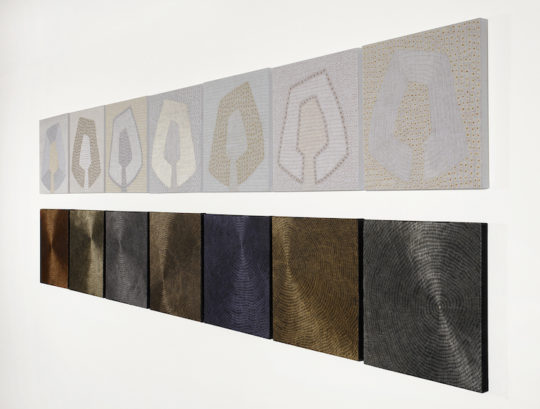

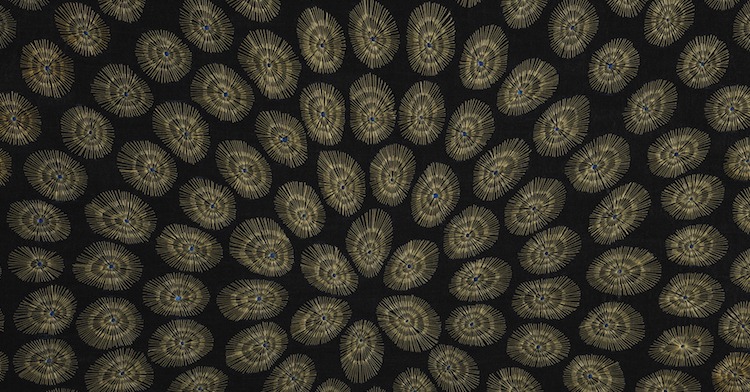

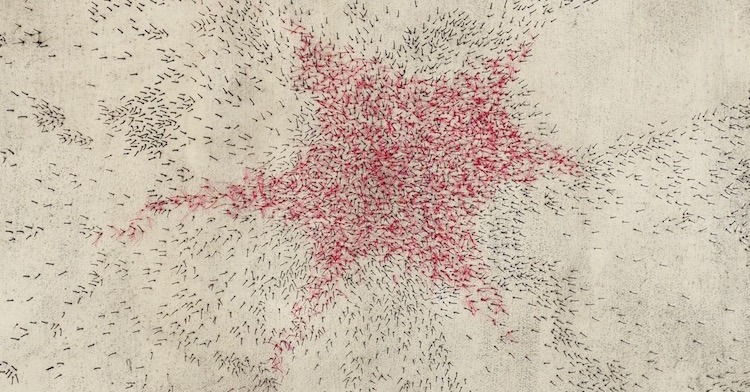

The untraditional embroidery makes for a meditative and meanwhile being a monumental form. I often work in series and build large works from smaller pieces. The small changes in each work communicate and often strengthen the relation to one another.

Do you use a sketchbook? If not, what preparatory work do you do?

I draw small sketches but also have a thought, an idea book. Sometimes it starts with just one word, a sentence that maybe ends up a title of a work.

Tell us about your process from conception to conclusion.

The start of a work can vary between starting to embroider in a corner, in the centre or on a piece of fabric. It grows and takes form along the way. With the sewing needle, I cannot hurry and I have enough time to reflect along the way. Due to practical reasons I often sew the larger pieces together from smaller pieces. I never sew a wrong stitch. No stitch is ever a mistake. A mistake is often what creates a dynamic in the piece.

I am colourblind. So sometimes the wrong colour is what catches the eye of the viewer. While I embroider I look forward to finishing so that I can start anew with another piece. The smaller pieces I sew in a parallel process and then it seems that I get finished more quickly. My sewing, the embroidery, I carry with me everywhere. It is important to be in the piece – let it follow me. A new work – a new possibility. Variations between large and small pieces are a necessity for my work situation. The small pieces give me a breather while my thoughts wander toward future works.

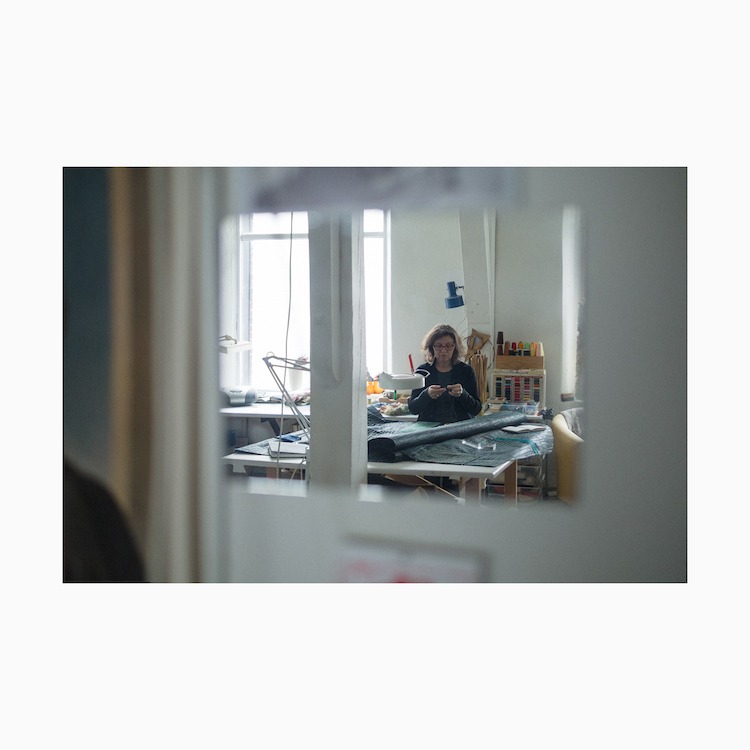

What environment do you like to work in?

Light and quiet are essential to me for good working conditions. My workshop, with the fjord right outside my window, is perfect. I am back to my roots, where I grew up by the fjord. The fjord gives me serenity even though the fjord and the water are never completely calm. Movement and unrest is always present. USF-Verftet, where my workshop lies, is a former sardine factory that is now filled with workshops of artists working in various mediums. I enjoy the quietude but also can be social when I choose.

The beauty in the simple

What currently inspires you?

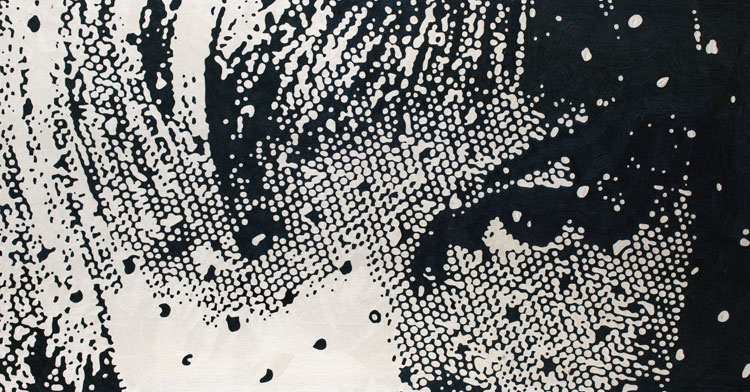

Nature, time, quietude, light and fragility have always followed me. Perhaps I feel unrest for the future. More and more my works are about light/shadows/transitions and interaction. Darkness and light that compliment one another. I illustrate this theme by using white and black, and tones in between them in the work future.

Who have been your major influences and why?

In 1987 while I was studying at Bergen Art Academy, I was on a trip associated with my studies to Senegal in Africa. That trip was soul stirring for me. All of those beautiful textiles. But also, the beauty in the simple. Repurposing. For me, it was like coming back to what was familiar in my own upbringing – to see it in perspective. All of the values that I want to preserve lay in this culture.

Tell us about a piece of your work that holds particularly fond memories and why?

The work “Screens” comprises three pieces – each section 68×110 cm.

- Screen with white lettering

- Grey screen with orange shadow

- Screen with a luminous secret

The large amount of embroidery primhol (prime hole) that I employ can perhaps seem exaggerated or meaningless like a visitor wrote in an exhibition guest book,

Don’t you have anything else to use your time on?

It is often so, that the seemingly formless happenings are that which may best express what it means to be a person.

I love the repetitious, that which grows slowly, the gradual – and then I’m there – finished! The coincidence, the accidental, the small deviations of the stitches, the small mistakes, a stitch too long or too short. This is what contributes to and creates life and wonder within the work.

The eye wanders, you discover new things in a fairly uniform field. Almost imperceptibly, these fields reveal nuances, an awareness of a delicate interplay is revealed. A dialog between these three pieces arises. This piece is owned by The National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design in Oslo.

How has your work developed since you began and how do you see it evolving in the future?

An artist´s career over a long period of time has a slow progression. But it also has a linear continuity. When I sit in my studio I often listen to audio books or the radio. Literature has always inspired me, the word. Writers express in words what I wish to visualize through my art in my pictures and works. That fascinates me.

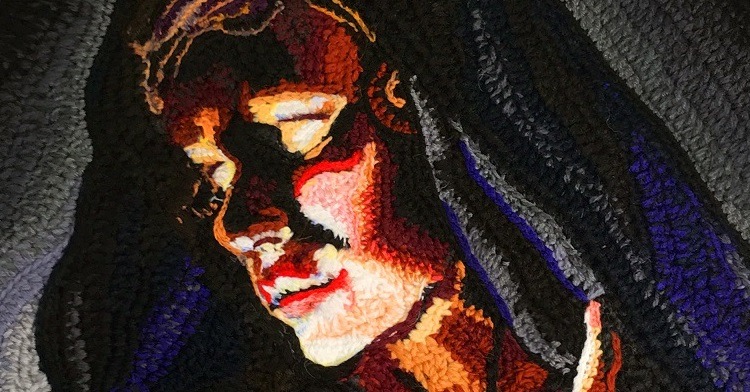

I recently finished a piece, ‘View’, inspired by the beautiful women’s garment, the burka. This garment with a fabric lattice in front of the face. What is it like to look at the world around you through a lattice? Beautiful, but also, frustrating. This work, ‘View’ (110×110 cm), is now hanging on exhibition and the public viewers can go behind the piece and experience the other art in the room from that perspective.

For more information visit: www.kunstguide.no

Let us know what your favourite aspect of the artist’s work is by leaving a comment below.

Comments