Artist Barbara Lee Smith received her MFA in Mixed Media close to her 40th birthday. Her work evolved from non-representational images to evocations of the land, sea and sky. Barbara is the writer of [easyazon_link asin=”094239139X” locale=”US” new_window=”default” nofollow=”default” tag=”textileaorg0a-20″ add_to_cart=”default” cloaking=”default” localization=”default” popups=”default”]Celebrating the Stitch: Contemporary Embroidery of North America and an honorary member of the Embroiderers’ Guild of England.

In part one of our two-part interview with Barbara we talk about being taught to stitch by her sister, why she only began to think of herself in professional terms at a later stage in life and she explains why she likes to work upside down.

“The dearest thing is Mother Love“

TextileArtist.org: What initially captured your imagination about textile art?

Barbara Lee Smith: I grew up by the Atlantic Ocean in a seashore resort. On the boardwalk was a needlework shop and I started doing small embroideries based on the kits they had there. KITS! How awful that seems now, but I loved working with the needle and thread and producing everything from tiny samples – “The dearest thing is Mother Love” given to me to do by my mother when I was ten years old and had three major childhood illnesses in the same year. I think she was reminding me of how much she was taking care of me, and all I wanted to do was cough or sniffle or scratch, depending on which illness it was at the time – to table cloths that were huge.

My mother refused to teach me to stitch, using her being left-handed as the excuse, but my older sister took me under her right-handed wing, and taught me, along with herself at the same time. It was bliss.

When I was a young mother I saw a wonderful article in a House Beautiful magazine that focused on the work of Mariska Karasz, a designer who also produced a book called [easyazon_link asin=”030870181X” locale=”US” new_window=”default” nofollow=”default” tag=”textileaorg0a-20″ add_to_cart=”default” cloaking=”default” localization=”default” popups=”default”]Adventures in Stitches . I borrowed that book from the library so many times that I was finally forced to buy it. I wanted so much to create my own designs by that time. Add to that [easyazon_link asin=”0713447680″ locale=”US” new_window=”default” nofollow=”default” tag=”textileaorg0a-20″ add_to_cart=”default” cloaking=”default” localization=”default” popups=”default”]Constance Howard’s Inspiration for Embroidery , also from the library and then finally my own copy, and I was totally, hopelessly smitten.

A move to the middle of our country where I saw an exhibit from our local embroiderers guild sealed the deal. I didn’t know there was such an organization! As soon as possible, I started taking lessons from one of the members and that hooked me further.

Teaching became part of learning when a friend called to tell me she had signed me up to teach a class in an adult education program. I had to learn in order to teach.

Times changed and so did I

What was your route to becoming an artist? (Formal training or another pathway?)

My route to becoming an artist had begun, but it was far from direct. Growing up in the 1950s in a very conservative family steered me to one of two possible routes of study. It was not assumed I’d have a career, but rather that I would have an education and then marry and repeat the process that my mother and her mother before her had followed: marriage, motherhood, church and being part of a community. My options were nursing and home economics. Since I wasn’t too keen on the sight of blood, home ec it was. I hated it, except for some of the sewing classes. What I loved was music, and I participated in as many music events outside the curriculum as possible. I also loved the one required studio art class and found I was pretty good at it. I graduated, married and started following the ‘career’ set out for me. Times changed and so did I, and I began to divide motherhood and family with more classes in art, eventually earning sufficient college credits to begin graduate work in art.

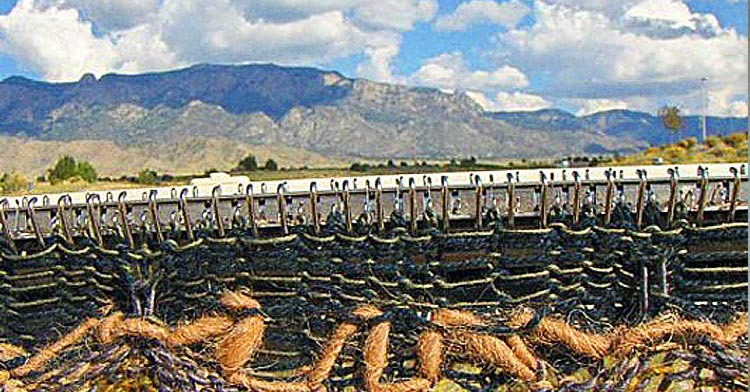

The only textile courses at the masters level in the university I attended (Northern Illinois University), were weaving or screen printing, and I didn’t fit in either one, so I majored in what was a ‘new’ course of study: Mixed Media. An out of the blue fellowship allowed me to complete my Masters in Fine Art and I began to think of myself in more professional terms. I was 40 at that point.

What is your chosen medium and what are your techniques?

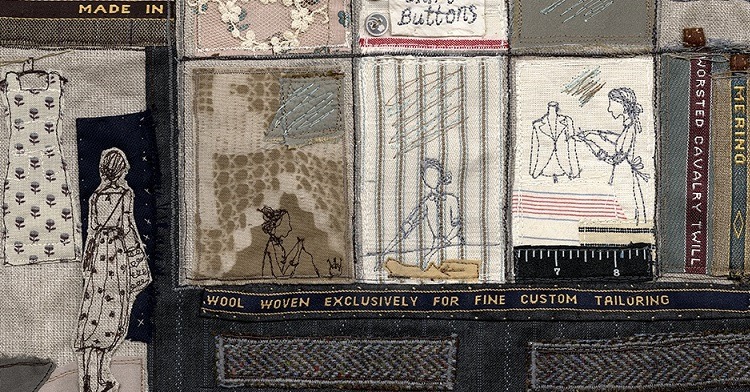

While I was a graduate student, I began to combine fabric printing and painting – new to me – with machine embroidery – a skill that I brought with me to the university. While the textile students weren’t too interested in what I was doing, the painting students seemed impressed. I didn’t really know what I was doing, but somehow it seemed right to me, so I pursued that, and I suppose it’s right to say that I have continued along the lines of combining paint and print and pigment with machine work of some sort for the past thirty-some years. I’m not finished yet, and I still find more to explore – not so much within the media, but with the ideas I can express with them. Mixed media indeed.

A different experience

How would you describe your work and where do you think it fits within the sphere of contemporary art?

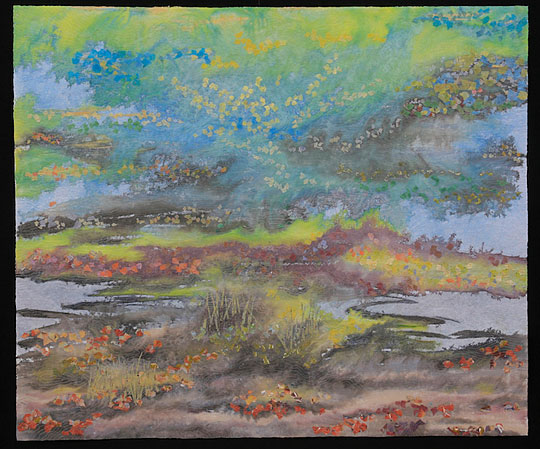

I think of my work as appearing like a painting from a distance and then offering a different experience when someone approaches it closely. My current work is inspired by the land and sea and sky that I experience both in my home environment in the Pacific Northwest part of the United States, but also where I travel. I stretch between works that have a representational aspect and those that are more abstract, but still based closely on the environment. I celebrate nature and hope that the work provides contemplative moments for those who take the time with it. I stretch between very small works that might be 6 x 6″ and very large works that stretch up to 15′ in any direction. I remind myself of Constance Howard‘s dictum to “Work big. You’ll see your mistakes faster.”

I prefer to leave to others where my work fits into the sphere of contemporary art. I am an artist. I work with mixed media and use a textile base for painting, collage and drawing (with a machine.) I am also reminded of the sculptor, Kenneth Snelson, who once remarked: “Hardening of the categories leads to art disease.” Audrey Walker calls herself a Maker. I like that too. I make things. I make what comes from within, stimulated by what is around me.

Tell us a bit about your process and what environment you like to work in?

I have a wonderful studio built over a garage. It has a beautiful view of Puget Sound. I live on an island that is small and hilly and where it is misty and sometimes rainy part of the year, but beautiful and sunny in the summer. The sun is marvelous, but like most artists who work in our area, we long for fall and winter so we can be inside and work.

I paint in part of the garage, just bringing the fabric (Lutradur only) outside to the driveway to dry. I use uncommon painting materials like foam brushes, rollers, credit cards to scrape the paint, hand-held sprayers for the pigments and rarely use a real brush. I use acrylic paint and silk pigments only.

I make a big painting and then have a long conversation with it to figure out what part (or all) of it that will become the ground for a work. I don’t think of the painting as a background, because it will become altered by the elements that I collage both over and under the translucent painted Lutradur. The collage elements are all made from the left-over bits and large pieces of previous paintings on the same material. There are no other materials used, and for me it is part of the challenge of composition to make this one material and paint form the entire work. Once the composition is complete, and multiple layers of the fabric are fused together (Wonder Under is the American name of the product for fusing) to form a stiff base, I start drawing. The work is turned face down on my industrial sewing machine and I begin stitching with a topographical or navigational-type map in mind. The final stitching both literally and visually holds the work together. I work upside down for two reasons. I want to introduce surprise into the work, and if I worked from the top, I’d be continually trying to stitch ‘within the lines’, as it were. From a technical standpoint, I work this way because I use a rayon thread in the bobbin that wouldn’t be strong enough to use in the top of the machine. This introduces the rayon sheen on the surface of the work.

In essence, that’s my process. Somewhere within it, I hope that magic occurs.

Different technical experiments

Do you use a sketchbook?

Of course I use a sketchbook! It’s both journal of sorts, lists of What If’s, Try This’s, sketches worked very small, lists of ideas and quotes; photos I’ve taken of a particular area that will help to document and inspire the work. When I’m working on a large project, I also document the samples of paints, pigments, and different technical experiments with what I did, what I used and how it came out. That’s also part of my research since I don’t want to keep reinventing the wheel.

For more information please visit: barbaraleesmith.com

You can read the 2nd part of this interview here.

If you’ve enjoyed this first part of our interview with Barbara Lee Smith let us know by leaving a comment below

Comments