When you’ve gained a reputation for creating art that makes the world sit up and listen, why not use that power to broadcast the planet’s need for social change?

That was how a series of politically-inspired, globe-shaped baskets gave form to international textile artist, Barbara Shapiro’s, concerns – regarding issues of exclusion and division, pollution of the world’s waters and social action in the pursuit of justice.

Involved in textiles from an early age, Barbara, a San Francisco native, began weaving in 1975 in New York City. Since then she has developed a rich knowledge of historic and ethnic textiles, along with broad technical experience in weaving, dyeing and basketry.

After her involvement in the San Francisco Art to Wear movement in the ’70s and ‘80s, she shifted her focus to non-functional textile art, creating beautiful wall hangings and sculptural baskets. Indigo dyeing is both her signature and her passion and is often used to enrich her weaving and basketry.

Barbara teaches workshops in basketry and indigo dyeing at universities and conferences across the US, and has taught at the Art Department at San Francisco State University as well as Osher Lifelong Learning Institute through SFSU.

A past Board Member of the Textile Society of America, she also serves as an advisory board member of the Textile Arts Council of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco and was a docent at the SF Museum of Craft and Folk Art.

Barbara’s award-winning textile art has been widely exhibited and published internationally. She writes for many textile publications and has served as an exhibition juror and guest museum curator.

In this interview Barbara takes us through the steps she followed, from concept to creation, as she formed her globe-shaped basket ‘Tikkun Olam: Repair the World’. Inspired by the concept of repair as artwork, she describes her use of and training in Japanese kintsugi – the repair of broken ceramics with lacquer and gold leaf – and how recycled tea-bags and fermented persimmon juice featured in the piece.

Name of piece: Tikkun Olam: Repair the World

Year of piece: 2020

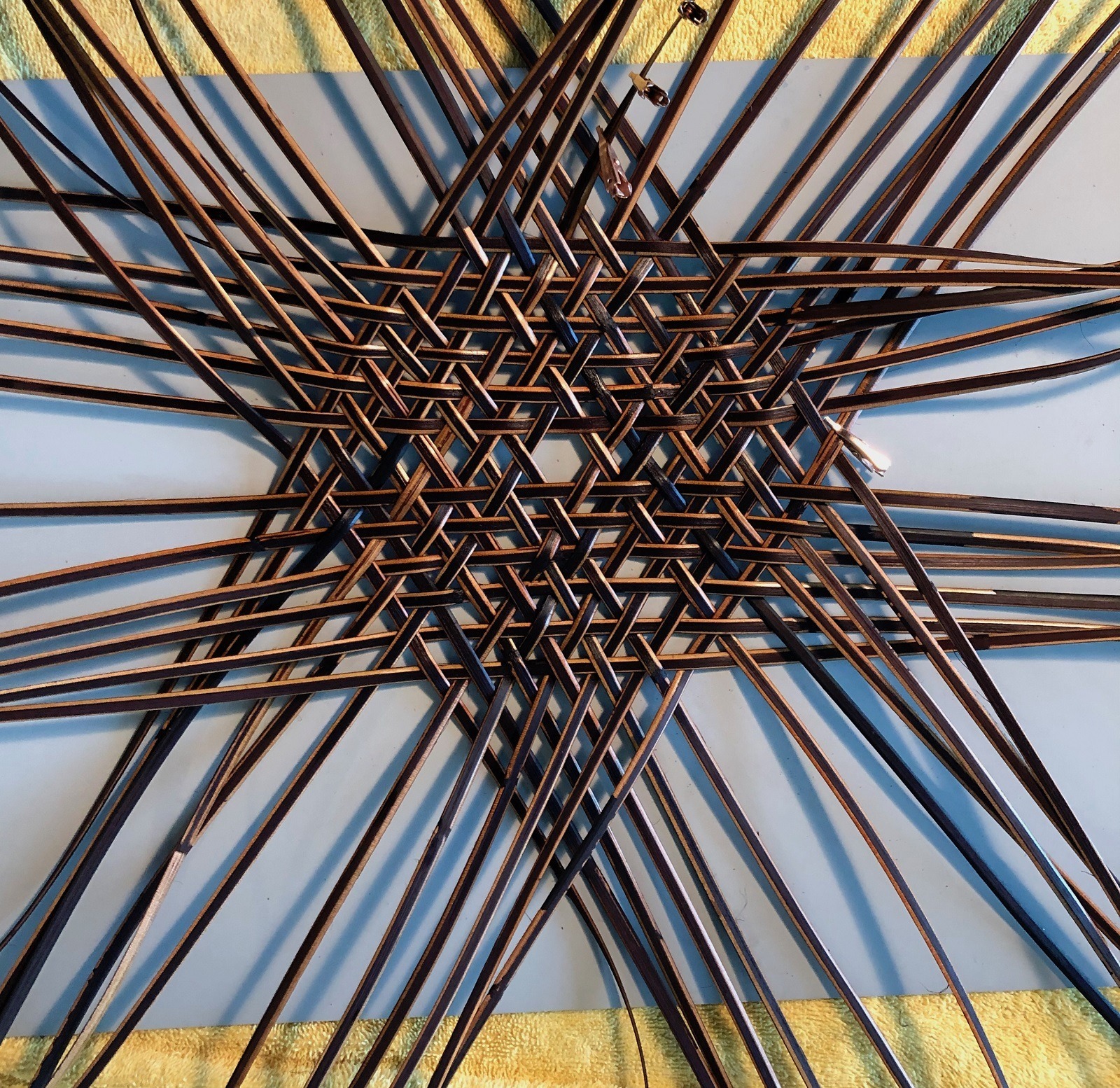

Techniques and materials used: 14 x 14 x 13H”, Techniques: Hexagonal plaiting, indigo dying, kakishibu coating, gold leaf application Materials: Sedori cane, tea papers, indigo, Kakishibu, raw kozo paper, gold leaf, sumi ink

Repair as artwork

TextileArtist.org: How did the idea for the piece come about? What was your inspiration?

In 2018 I started a series of politically inspired, globe shaped baskets. I do not often create work with a political perspective, but recent events moved me to speak my mind, albeit in a quiet voice. The first, called Strength in Diversity (2019, 12 x 12 x 12”), was my response to a growing division among citizens of the US.

The globe is plaited in hexagonal technique interlaced with handwoven bands of various bast fibers and paper (gampi, hemp, linden, straw, indigo dyed ramie, nettle, mulberry, kudzu, fique, coconut). Bast fibers have been used by common folks for centuries whereas silk and cotton were luxury fibers for use by nobility and the wealthy. My response to exclusion and division is Strength in Diversity.

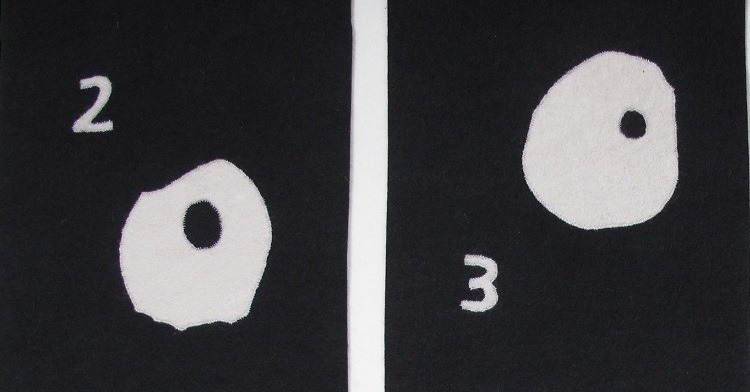

The second, called Troubled Waters (2019, 13 x 13 x 13”), reflects my concern for the pollution of our natural environment, especially the waters on which all life relies. Laws protecting the environment are being stripped away in the US and I find this frustratingly short sighted. This plaited cane globe is embellished with dyed and inked paper and cloth debris, symbolizing the pollution of our waters. There is a pool of these materials inside the bottom of the basket reflecting what we see, instead of limpid waters, when we look into our rivers, lakes and oceans.

The third basket, the subject of this interview, is Tikkun Olam: Repair the World, (2020,14 x 14 x 13”.) It was conceived of as a response to the huge 2019 fires in Australia, evidence of the effects of global warming on our small planet. As a Californian, those Australian fires had brought back memories of recent ones we had experienced, fires that took the homes of some dear artist friends. When the Corona Virus upended our lives early in 2020, it seemed appropriate to continue with the theme of repairing the world.

After some time spent planning, I was ready to start plaiting in my new studio in mid-March. As I write this article, California is burning once again, and we have suffered from very smoky air for weeks all the while dealing with a pandemic. The Hebrew words Tikkun Olam: repair the world have come to suggest social action in the pursuit of justice. Today, our world and our lives are in need of repair on so many levels.

What research did you do before you started to make?

Decades ago, I acquired an interesting piece of Japanese ceramic at an auction. The subtle, incised, geometric pattern contrasted with some strange irregular gold lines running through the piece. I later learned this was Japanese kintsugi, the repair of a broken ceramic piece with lacquer on which gold leaf is applied, highlighting the repair rather than concealing it.

Last year I actually took a class in this technique from David Pike, a Japanese-based American kintsugi expert. I made several repairs to broken ceramics in the months after that class.

The concept of repair as artwork has been part of my own textile art practice for many years in my collaboration with wood turner Chuck Quibell. He gives me his occasional imperfect bowls that have cracked in the drying process or gotten too thin on the bottom as he strived for the finest turning. I use textile techniques of coiling or darning to fix these bowls in the long tradition of women repairing things. The bowls have won awards in the wood turning world and one was exhibited in Mending = Art curated by Diane Savona.

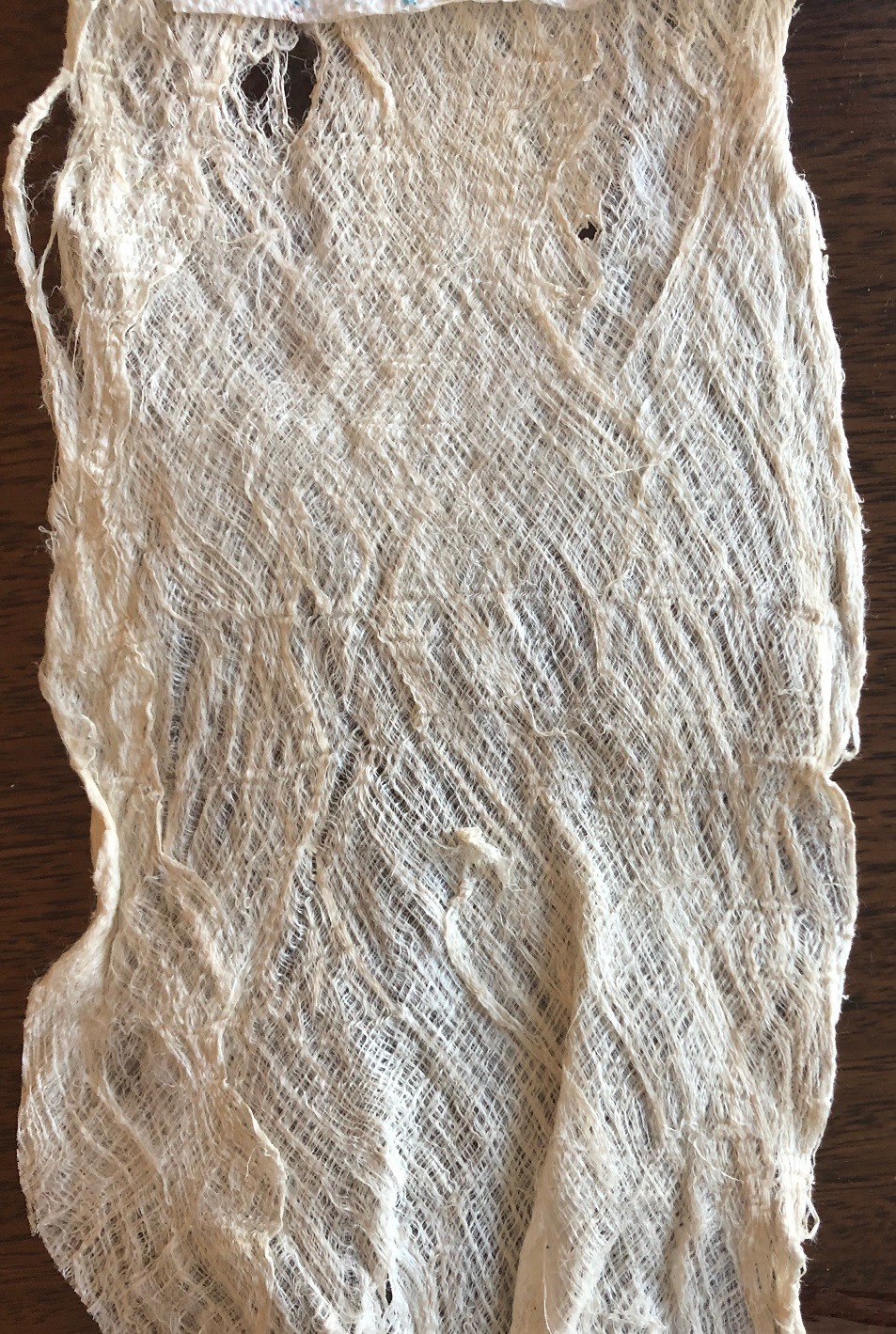

I love the Japanese tradition of giving a basket, often a worn utilitarian basket, a new life by covering it with recycled paper coated with kakishibu, fermented persimmon juice. I have a couple of Japanese examples in my collection and have used the technique in a number of my sculptural baskets such as Unwrapping Memory.

Natural materials and techniques

Was there any other preparatory work?

I did some quick sketches and then made a small maquette of the plaiting technique and materials to be used for the skin and repair. My maquette included stitched mending, but I rejected this idea as impractical and unnecessary to my vision of a kintsugi inspired repair.

To create the skin for Tikkun Olam: Repair the World, I used recycled teabags, which are made of strong thin abaca paper. I drink enough tea to have accumulate stacks of these small precious rectangles. I open up the bags, compost the tea, wash and dry the papers flat, and dip them into indigo halfway.

For this project I coated a bunch of these two-toned papers with kakishibu, fermented persimmon juice, and let them cure to a nice dark reddish-brown hue in the sunlight. The persimmon is self-polymerizing and strengthens, waterproofs, and gives the paper a sheen.

What materials were used in the creation of the piece? How did you select them? Where did you source them?

The globe is plaited with sedori cane from Japan. Sedori means scraped in Japanese. The top of the beveled shiny side of the cane is scraped off, exposing some of the pithy fiber. This, like the underside of the cane, takes dye well, leaving a light-colored undyed stripe along each un-scraped side. I sourced this cane in Tokyo on a recent trip and have dyed a lot of it in indigo myself for other baskets.

The tea bags were easy to come by. I could have used other types of handmade paper, but I liked the idea of reuse. My kakishibu, fermented persimmon juice, came from Japan, but can be ordered online in the US. It was also used to adhere the tea papers to the cane. The repair patch was made of raw kozo (mulberry) paper which is strong and very textured. I coated it with gold textile paint as an adhesive, Italian gold leaf, and sumi ink.

What equipment did you use in the creation of the piece and how was it used?

My equipment are my two hands, a few basketry tools and brushes. I also use my camera to document the process for further explorations.

Creation of the basket

Take us through the creation of the piece stage by stage

In February 2020 I moved my art studio to San Francisco in a building next to where we live … so fortuitous with the general confinement that was soon to come. After some time spent organizing my new space, I was able to start working in mid-March. I could see the Grand Princess cruise ship moored in the middle of the Bay with Covid19 positive passengers and crew still aboard. The pandemic was constantly on my mind and remains so.

With my maquette completed, I went to work plaiting a large globe-shape in hexagonal structure with an opening on the top. While it dried, I prepared the skin for my globe by coating the indigo-dyed tea bag papers with kakishibu and curing them in the sun. Using more persimmon juice as an adhesive, I put about a third of the skin on what would be the back of the form to see what it looked like.

Then I drew a stencil of the gash I wanted to cut out and transferred this shape to the, still uncovered, front of the basket surface. I carefully cut out the shape and was relieved that the globe did not fall apart even with the large piece removed. A bit of glue made sure it all stayed in place. I adhered more torn pieces of the tea bags covering about 2/3 of the surface in all, creating continents and oceans. Sumi ink was added as necessary for depth.

I used the removed piece of plaited cane to draw a slightly larger shape on the raw kozo paper and cut that out. This kozo repair piece was coated with gold textile paint as an adhesive and then real gold leaf. The back side which would be visible inside the basket was coated with persimmon and cured. The repair patch was glued to the inside of the globe. Sumi ink created deeper shadows here and there, and the work was finished!

What journey has the piece been on since its creation?

The Mendocino Art Center hosted a Bay Area Basket Makers exhibition with Tikkun Olam: Repair the World in Summer 2020.

Other recently exhibited works include:

Strength in Diversity, National Basketry Org. Members in Print, 2020

What Knot: Top Knot, National Basketry Org. Basketry Now 10th Anniversary Exhibition, 2020

Top Knot II, Handweavers Guild of America Small Expressions, 2019

Unwrapping Memory, Surface Design Association, Home – Holding on and Letting Go 2019

Coiled Sakiori with Suki Ball, Mt Koya Temple, Japan, 2019 and Nagoya, Japan, 2018

Unwrapping Memory, NBO Members in Print, 2018

Sedori Vessel, HGA Great Basin Basketry Exhibit, First Prize, 2018

For more information visit www.BarbaraShapiro.com

Have Barbara’s tips and techniques inspired you to try something different? Let us know in the comments below.

11 comments

Bernie

I love what you are doing! Many years ago I noticed that teabags never broke down in the compost heap, so like you I started to save them also! I enjoy the meditative process of emptying, flattening and storing in flat boxes, for use later. When I first visited Japan in the 1980’s I was intrigued by their process of Kintsugi. I’ve created 3D and 2D works combining these two processes. Really enjoyed seeing your work

Rita

Beautiful work. I had read about persimmon a few years ago in an article on Japanese textiles it was used to coat clothing as a waterproof.

Barbara Shapiro

I bought quite a bit from a textile supply company when I was in Kyoto, Japan. You may be able to order from them if you can find and navigate the Japanese website. Sometimes there are vendors on Amazon in the US where I see it occasionally. I went to Amazon.au and found two types when I searched: Shimamoto Natural paint dye and Turner odorless persimmon juice. You might look into these, but I have no experience with either. Persimmon does have an odor, but it fades with time. It is very important to get someone to translate the instructions for you. The product must be kept airtight if it is the true self-polymerizing persimmon liquid made from fermented ripe persimmon fruit and not just a paint. The ones I get come in a plastic container that you roll up as you use it, so no air gets into it. You paint it on or dip fabric into it and let it cure in the sun. It’s it gets progressively darker with time and with multiple layers. But please do a thorough reading of the instructions to get full information on use. Best of luck.

Trish Downie

I so enjoyed looking at your work Barbara. I live in New Zealand and would love to buy fermented persimmon, which company can I contact ?

I’m an fabric artist mainly but also a book maker.

D.Sharma-Winter

a rich and lushly inspirational article, thank you Barbara for sharing your work so generously

Margaret Roberts

What an excellent article. I have followed Barbara’s work for many years and was thrilled to see her art pieces in basketry especially Tiikuun Olam.

Margot

Unique, special, sacred work. Thank you

Wendy

Beautiful imaginative work! Thank you for sharing so much of your creative process!

r

your poor hands!!

i admire your innovative use of such diverse elements to create such intriguing installations.

Cindi Gray

Thank you for sharing your work in your process! I love the improvisational nature and your willingness to see what shows up. To me, I give it so much more meaning to know your thoughts and the way social justice issues can drive creativity.

Barbara Shapiro

That’s persimmon on my hands, and it washes off if you don’t let it dry too much.

Barbara