American visual artist Bonnie Peterson is deeply passionate about environmental sciences and the great outdoors.

She uses embroidery on silk and maps to raise awareness about the impact of global warming, advocating for the natural world she loves.

By engaging with scientists and asking insightful questions, Bonnie strives to make the science of climate change more accessible. While understanding equations, graphs and statistics can be daunting for many, they’re second nature to Bonnie, thanks to her background in marketing and market research.

Now Bonnie uses her ability with numbers to translate complex scientific data about climate change into easy-to-understand visual narratives that are central to her work.

Her materials are silk, velvet, thread, maps, old journals and history. Her tools are words, numbers and graphs. Bonnie’s use of colour, collage, mark making and embroidery creates a magical blend of art and science that sparks conversation and inspires action.

Bonnie Peterson: I’m a visual artist investigating environmental and social issues using embroidery on silk and maps.

My work is primarily narrative and integrated with data and history. It examines geophysical climate issues with the goal of promoting a fresh opportunity to consider climate change and an urgency to take action.

I’ve always been fond of maths – I worked with data and graphs during jobs in marketing and marketing research. I think this, and my college statistics classes, fostered my interest in promoting graphs and related maths with climate issues.

I design simple explanations of the important principles and difficult modelling scenarios in environmental science. By incorporating these in my work, I hope to break down some of the maths-phobic barriers confronting climate maths and climate graphs.

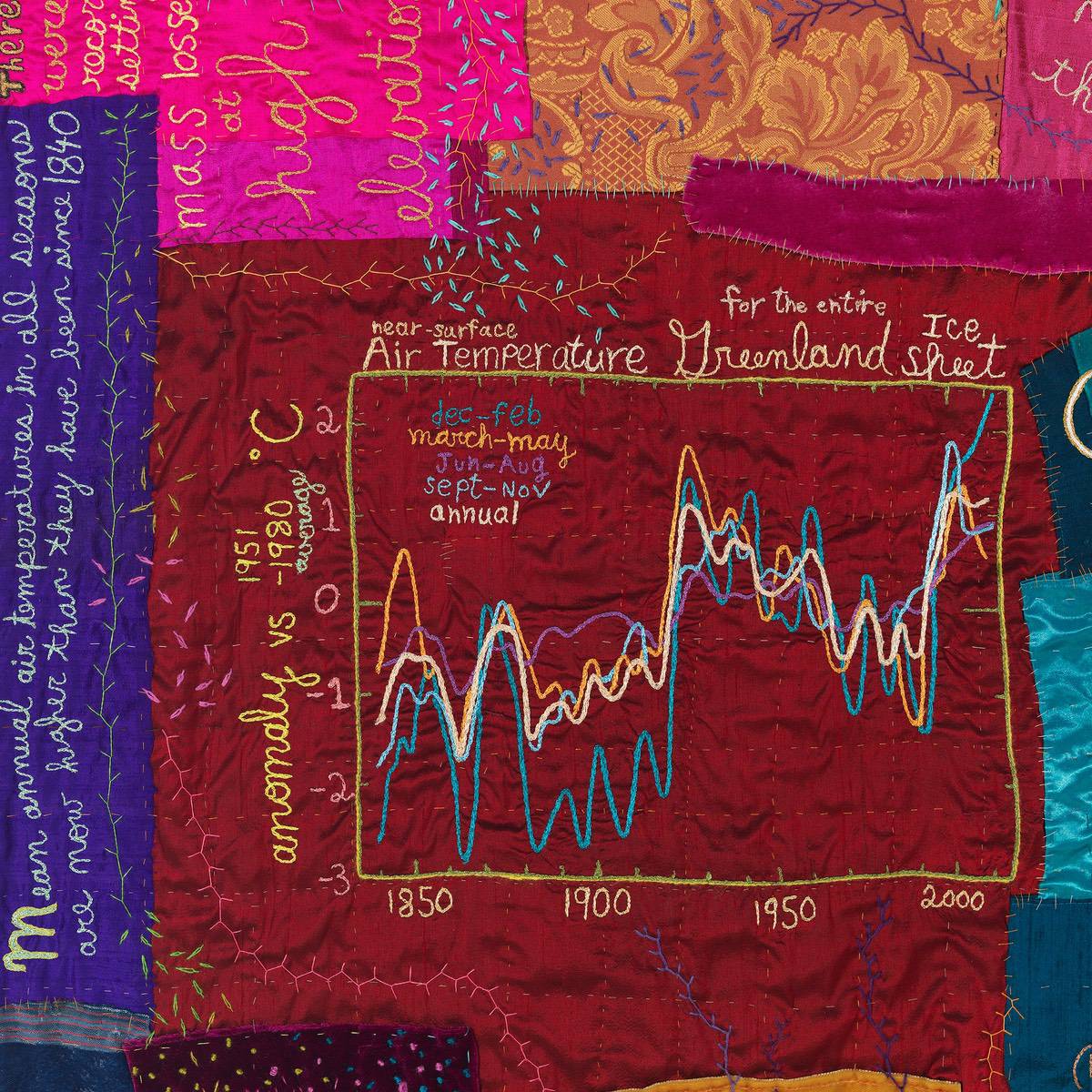

For example, Turning Green illuminates data about the melting of Greenland’s glaciers using text, temperature and other recent climate data from NASA and the Jet Propulsion Lab research studies. I find it fascinating that this data is collected by twin satellites measuring gravity.

A basic understanding of the measurements and methods aids critical thinking, leading to more interest and acceptance of the consequences of warming.

Inspiring data

I am interested in the technical aspects of environmental data collection – I want to understand the mechanism behind the numbers, and the context and relevance of the data.

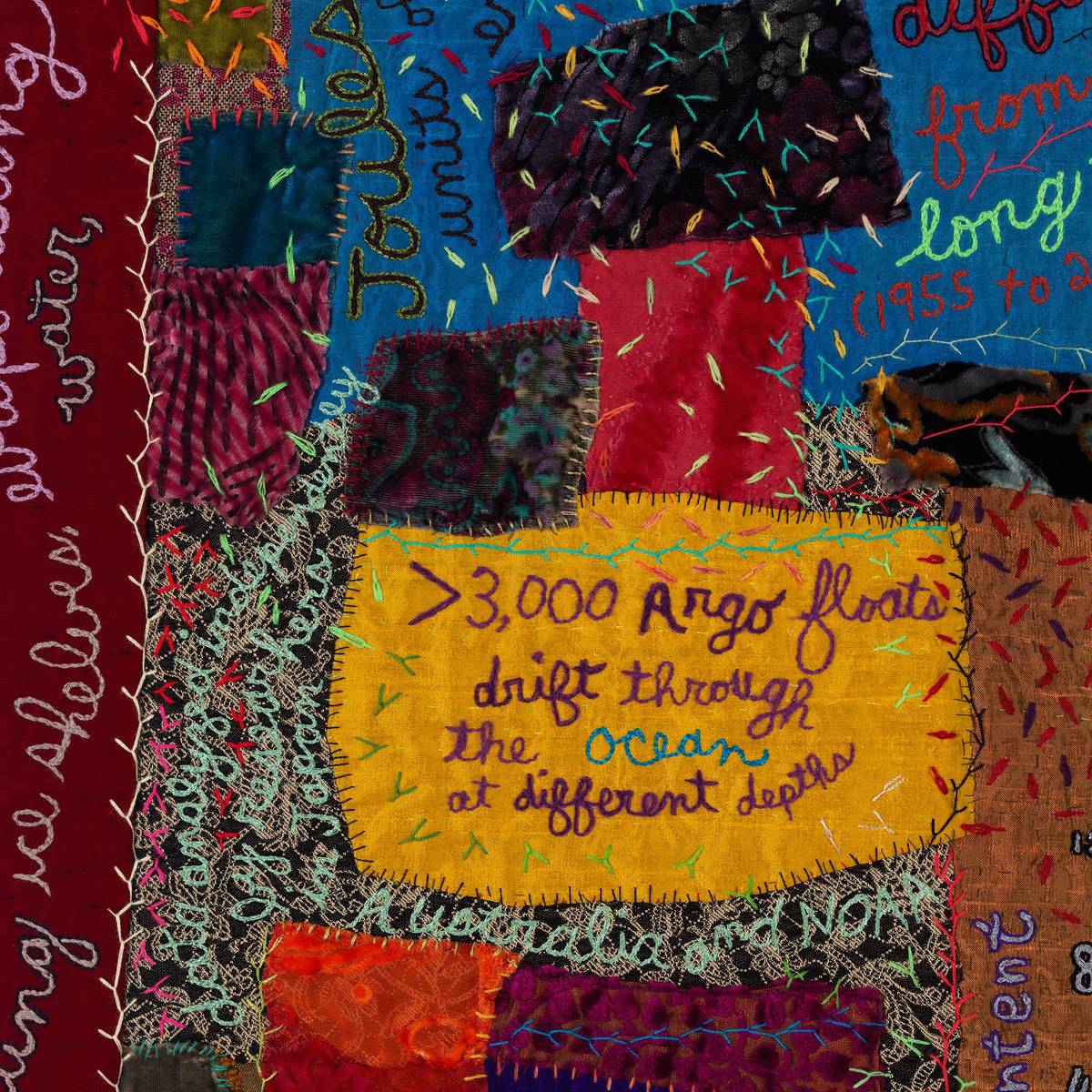

For example, Argo floats, which feature in Ocean Heat, collect data on ocean characteristics such as temperature and salinity. Ocean Heat shows heat content in the top 700 metres (2,300ft) of the ocean, plus data collection tools and the relevance of heat content to climate science. This artwork promotes an understanding of the physical science behind warming.

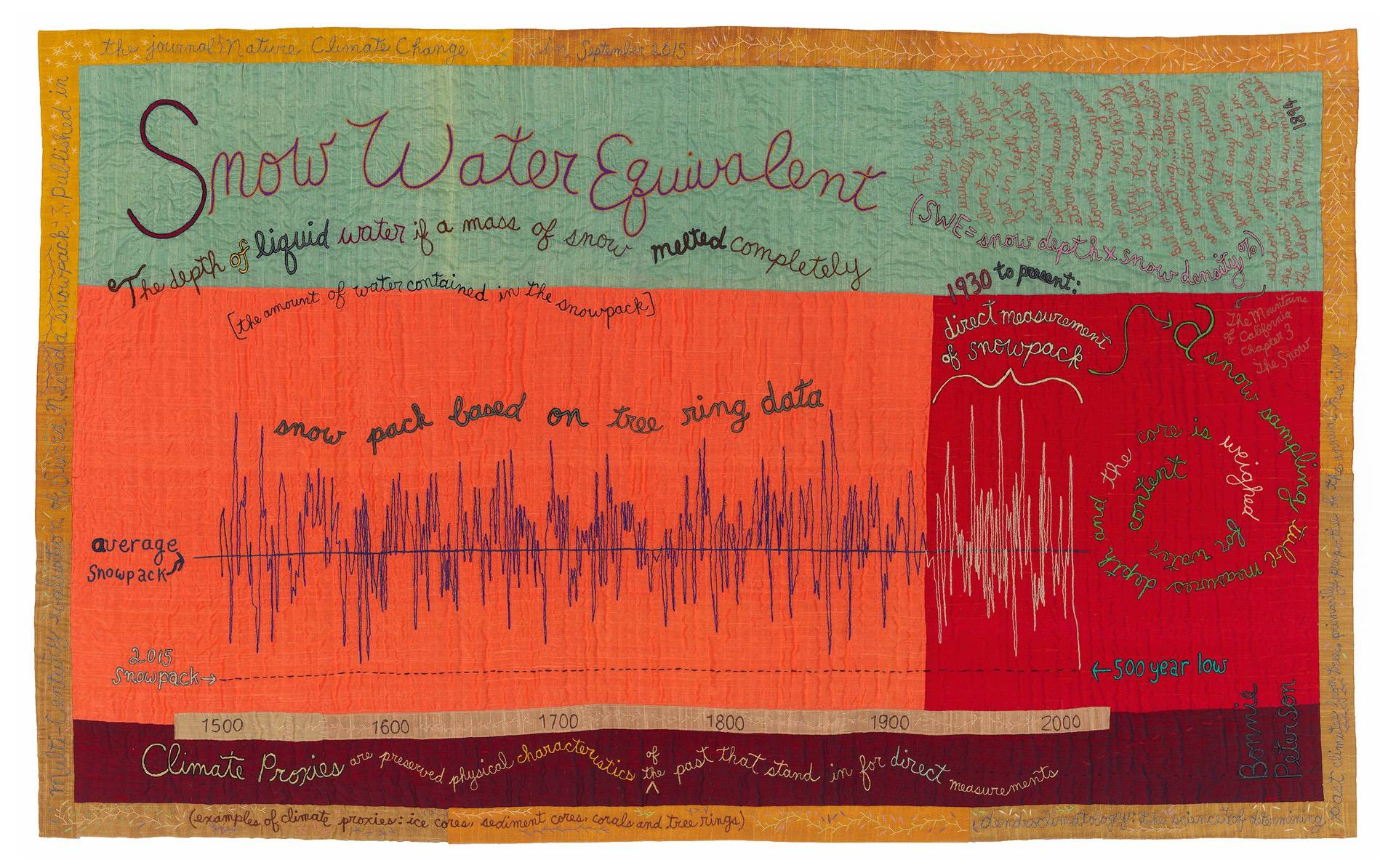

Drought explains how snow water equivalent data and tree ring science were used in 2015 to record the worst drought in California in 500 years. The goal of Drought is to engage viewers in the scientific process and lead to a greater understanding of the changing background conditions brought on by global temperature increase.

‘The science and maths behind climate equations, graphs and models are fascinating and seldom brought to the fore.’

Bonnie Peterson, Textile artist

Text & texture

Text is an important feature of my work. It has evolved from applying text using transfers to using free motion embroidery.

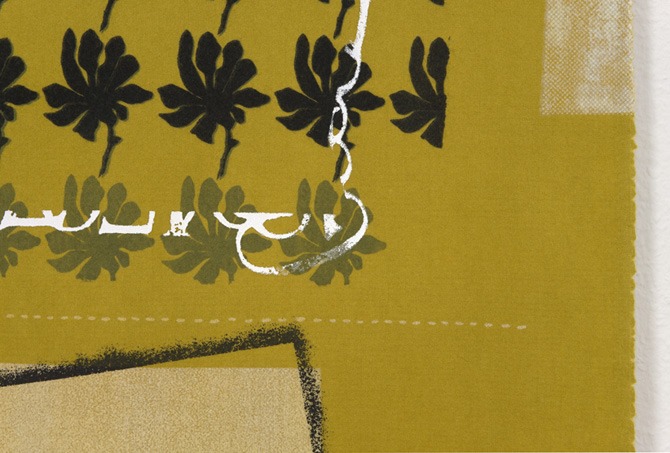

Mixing a variety of source materials such as scientific data and early explorer’s journals, I stitch words and graphs on velvet and silk fabrics to make large narrative wall hangings and a series of topographic maps.

I annotate topographic maps with a labyrinth of climate variables at various future temperature and emission scenarios.

‘Stitching is a key element and I use a mix of hand and free motion embroidery.’

Bonnie Peterson, Textile artist

The surface of my work is a blend of appliqué and piecing, although not necessarily done in the traditional way. For example, sometimes I attach transfers with big suture-type stitches.

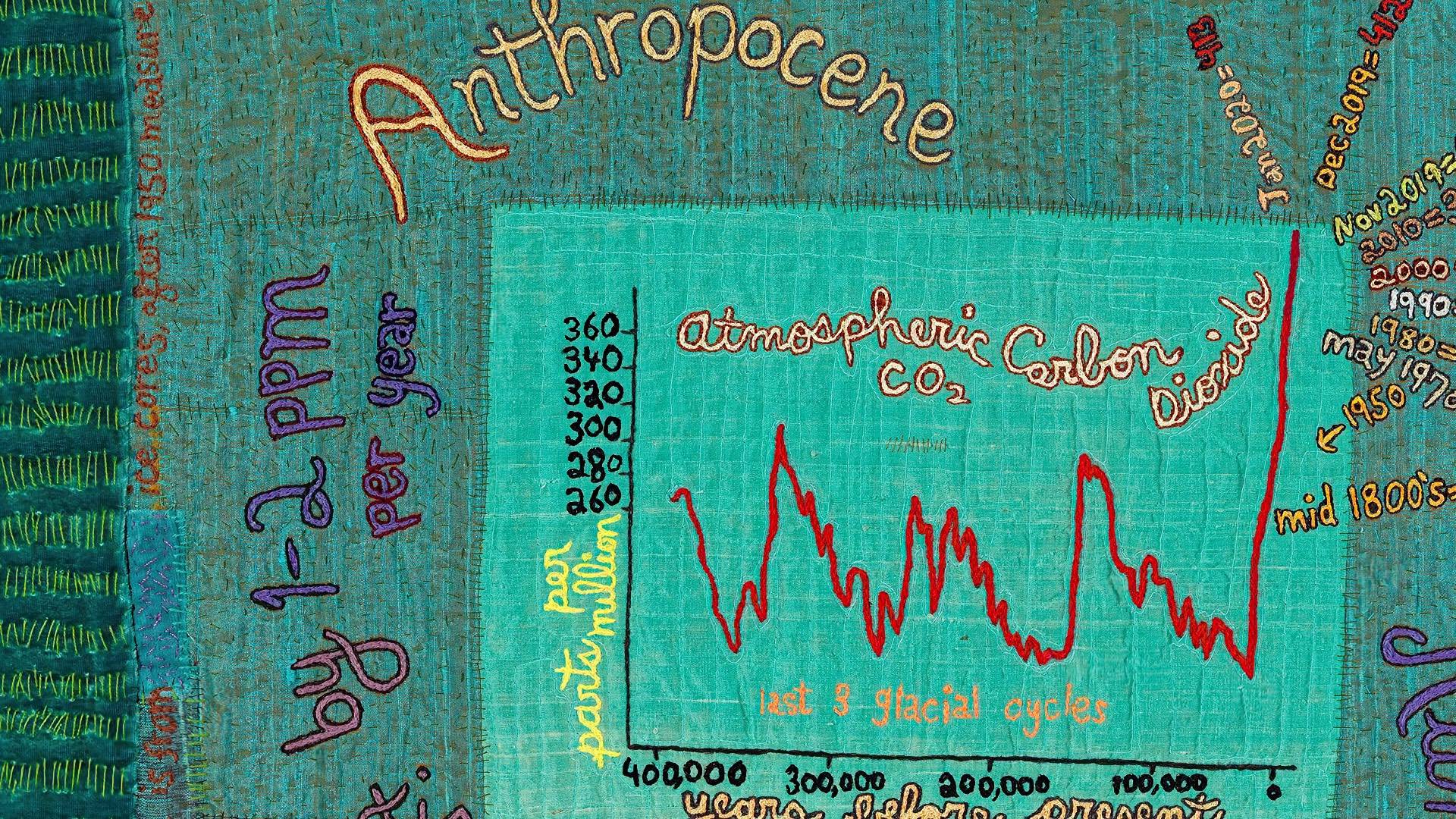

I enjoy adding hand stitches, crewel and crazy quilt stitches to random sections of my work. In Anthropocene CO2, I’ve used traditional Kantha stitches in the velvet borders.

Science inspiration

I subscribe to a wide variety of web sources and journal articles for new climate research and to get a fresh look at climate science. The journal Nature is an excellent starting point.

There are an increasing number of reports about the negative aspects of climate change on the human body as the prevalence of heat waves increases dramatically.

I organise information on a variety of environmental and social topics in real and virtual folders. I then sift through the research related to a topic of interest that I want to spend more time developing into a piece of artwork.

I research the history of a topic and the data collection instruments such as satellites and ocean floats. Sometimes I will email a researcher to ask a question, to ask for more recent data, or for a different graph.

This process can take months, so I usually work on several projects at one time to allow sufficient time to work out kinks and make decisions.

‘I find that if there is a stopping point in a project, it turns out to be a good thing because it helps clarify an issue or thought.’

Bonnie Peterson, Textile artist

Making sense

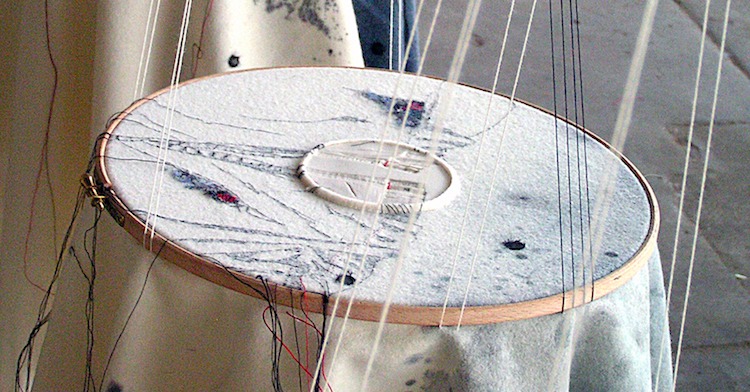

I assemble the background fabrics on a pin-up wall. Sometimes I photograph different fabric and thread colours to see what works.

Multiple layers of fabric usually require pin or thread basting. The centre layer is usually cotton flannel, which can withstand a hot iron.

Free motion embroidery is not computerised machine stitching. It’s where the ‘feed dogs’ are lowered and the hand moves the fabric in the style of writing. I like the happenstance of penmanship and the irregular sizes and spacing of words and numbers.

‘When I’m using free motion embroidery for text or a graph, I prefer to wing it rather than start with a marked line.’

Bonnie Peterson, Textile artist

Free motion embroidery needs a stabiliser or a thick surface, so I use various methods to keep the thread from becoming twisted beneath the embroidered surface.

Solvy water soluble film, paper, tear-away or dissolving stabilisers or even just using a thick fabric surface helps with this problem.

I am interested in value, colour and contrast. I use a wide variety of threads from small diameter (such as size 40) cotton and polyester threads to thicker (size 12) wool, acrylic and rayon.

Silk thread is more difficult to find. I use all of these, whether doing hand stitching or free motion embroidery. Madeira is a source for the thicker rayon and wool threads and sparkly threads. I like the neon colours.

Exploring light

I love the shine and the directional nap of silk dupioni – it’s nubby and irregular. I like it as a base for embroidery. Different colours and reflectivity come out with various orientations of the fabric.

There are colour differences in the warp and weft. Velvet has some of these same properties in its differential shine and nap patterns.

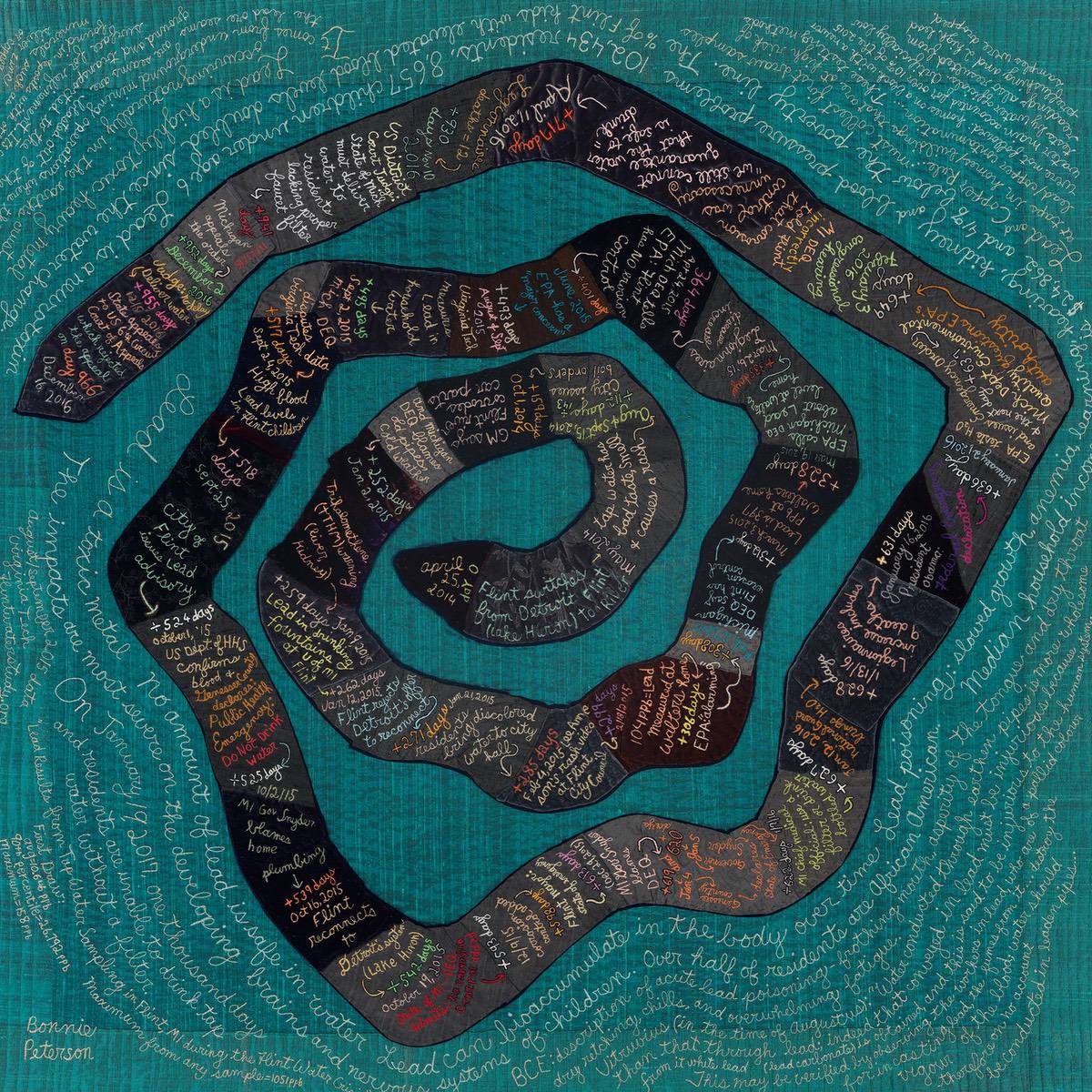

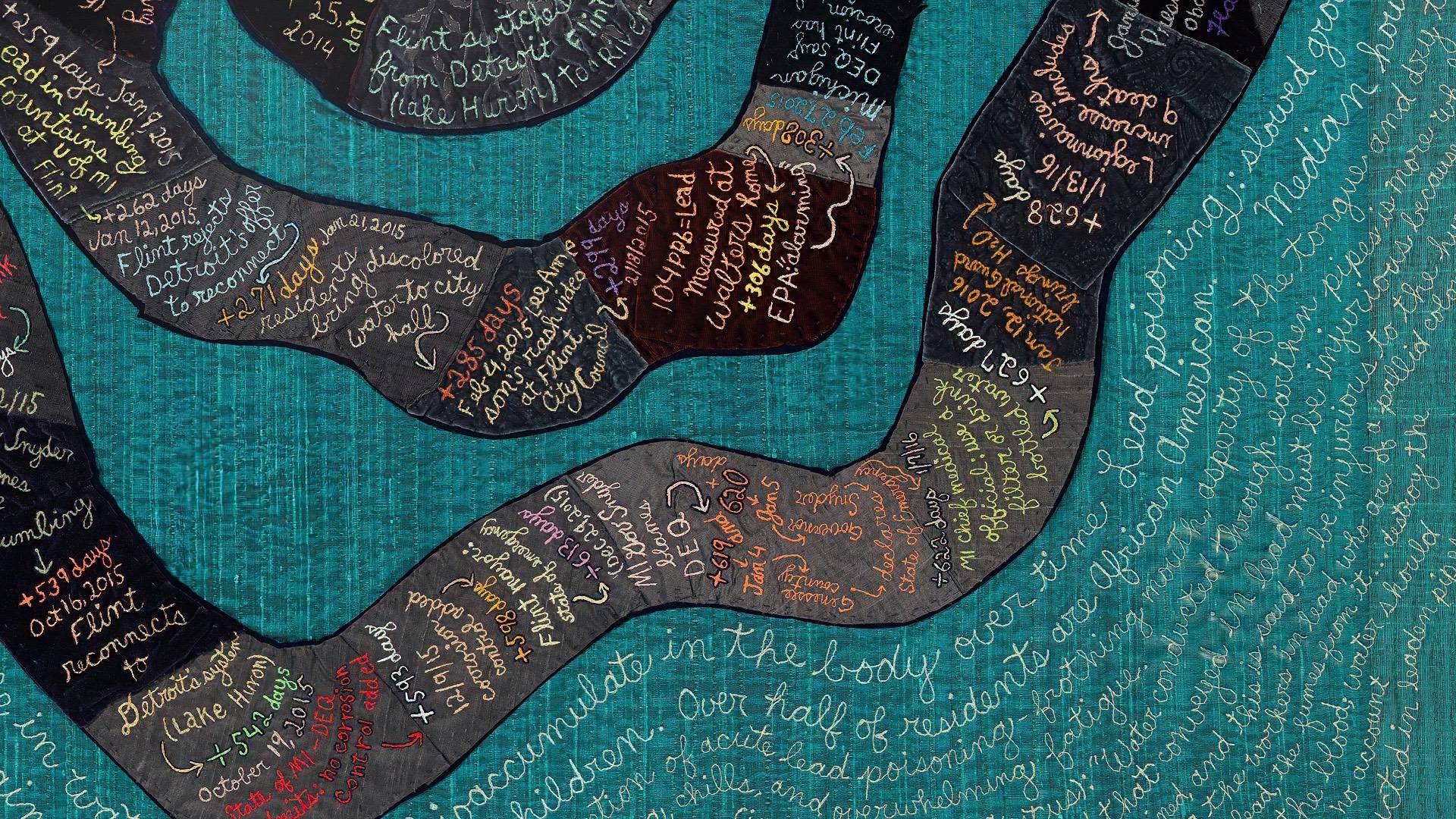

In Days of Lead, you can see how I’ve used silk dupioni mixed with velvets. The artwork chronicles significant events during the first 1,000 days of toxic lead (Pb) in Flint, Michigan’s water supply, as well as environmental details about lead (Pb).

Both of these fabrics are difficult to find so I am always on the lookout. Mood Fabrics in New York City has unusual devoré or burnout velvets, and Silk Baron in Los Angeles has all kinds of silk and velvet.

Cool collaborations

I love partnering with scientists. Artist-scientist projects are a lot of fun because of the camaraderie, and the science is fascinating. Collaborations on concepts in fire ecology, atmospheric science, permafrost and other geosciences have driven my work.

I’ve participated in some exciting and rewarding projects including the University of Wisconsin, around issues of limnology – lake science and climate change; glaciology at Yosemite National Park; fire ecology at Northern Arizona University, exploring the intersection of extreme fires and societal change; dendrochronology, the science of dating tree rings, at the University of Arizona, as well as the declining mass of Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets, and permafrost melting.

Changing minds

The first project ‘Paradise Lost’ started in 2006. The University of Wisconsin-Madison brought artists and scientists together in Northern Wisconsin to learn about climate change.

Our goal was to make art for a travelling exhibition. The topic was not at the forefront of people’s minds as it is today.

That was the year former United States Vice President Al Gore’s movie, An Inconvenient Truth, came out. The terminology was transitioning from ‘global warming’ to the less confrontational ‘climate change’.

I was able to indulge my curiosity by asking many questions of the atmospheric scientists. I became interested in the CO2 graphs made from ice cores and I used one of those graphs in my work.

Anthropocene (CO2) depicts 400,000 years of CO2 in the earth’s atmosphere. The Anthropocene Epoch is a unit of geologic time, used to describe the most recent period in Earth’s history when human activity started to have a significant impact on the planet’s climate and ecosystems.

On fire

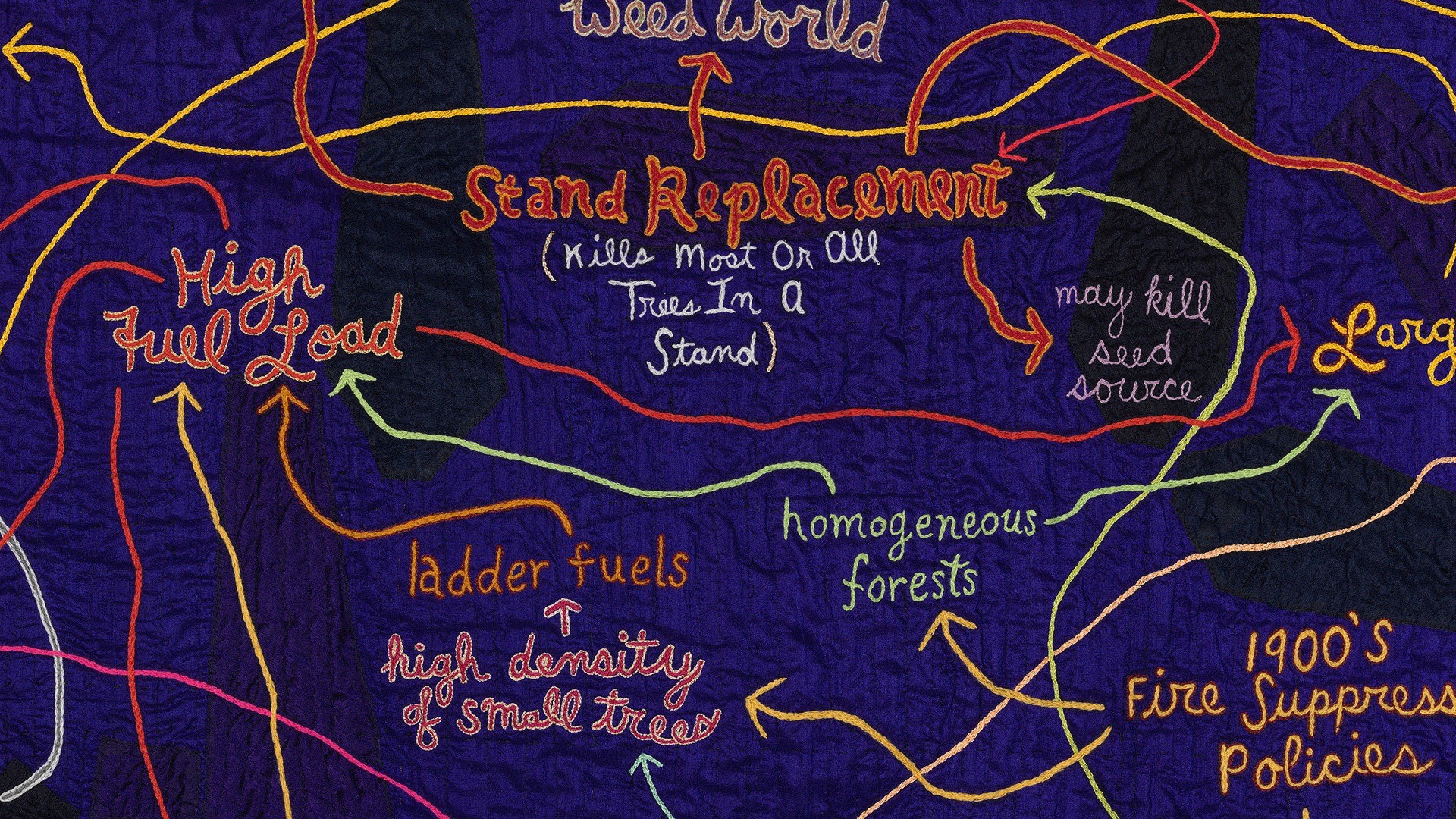

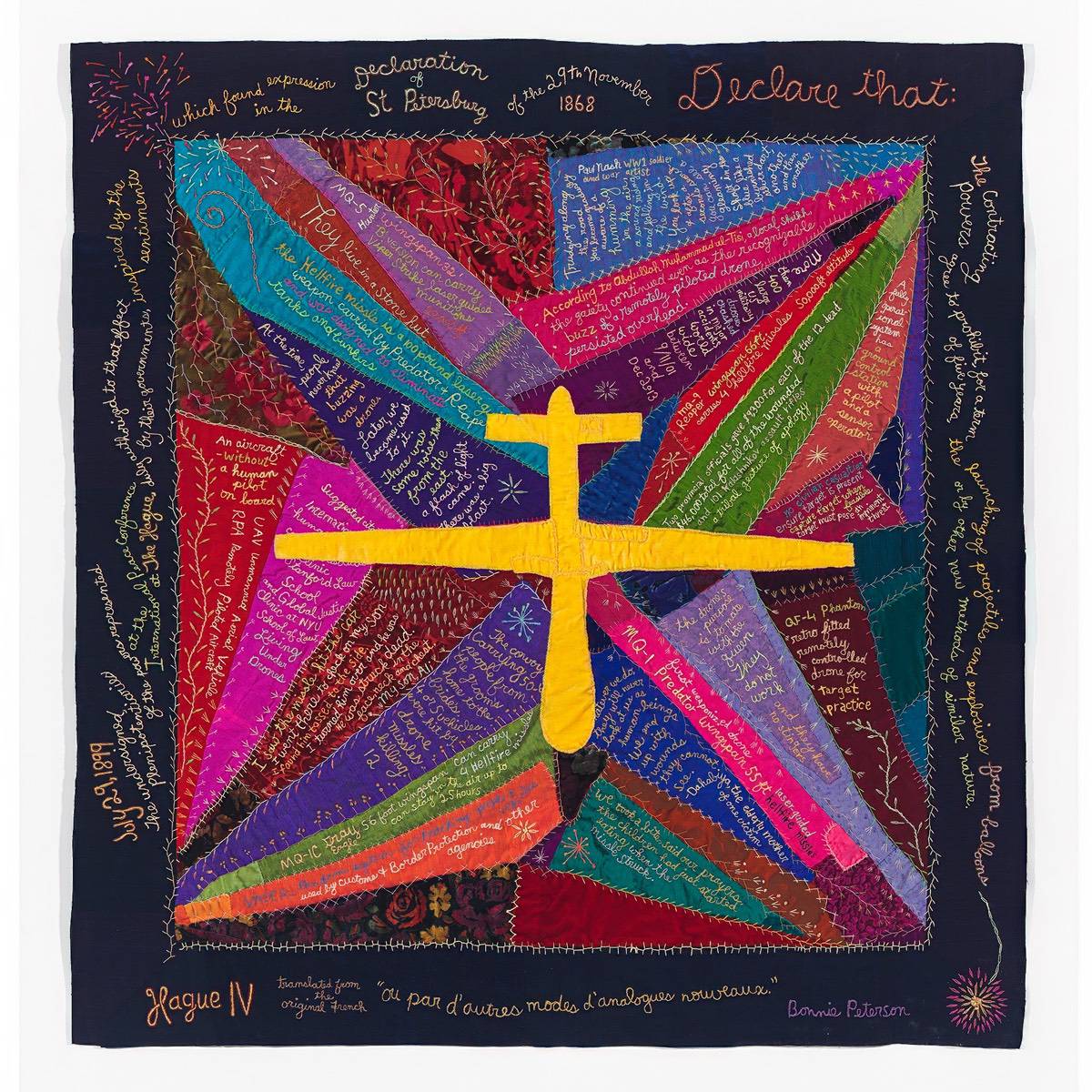

Fires of Change: The Art of Fire Science was an artist/scientist project that explored how fire as an ecosystem process is impacted by climate change and societal development. Eleven artists attended educational field trips to the North Rim of the Grand Canyon and other locations with fire managers and scientists.

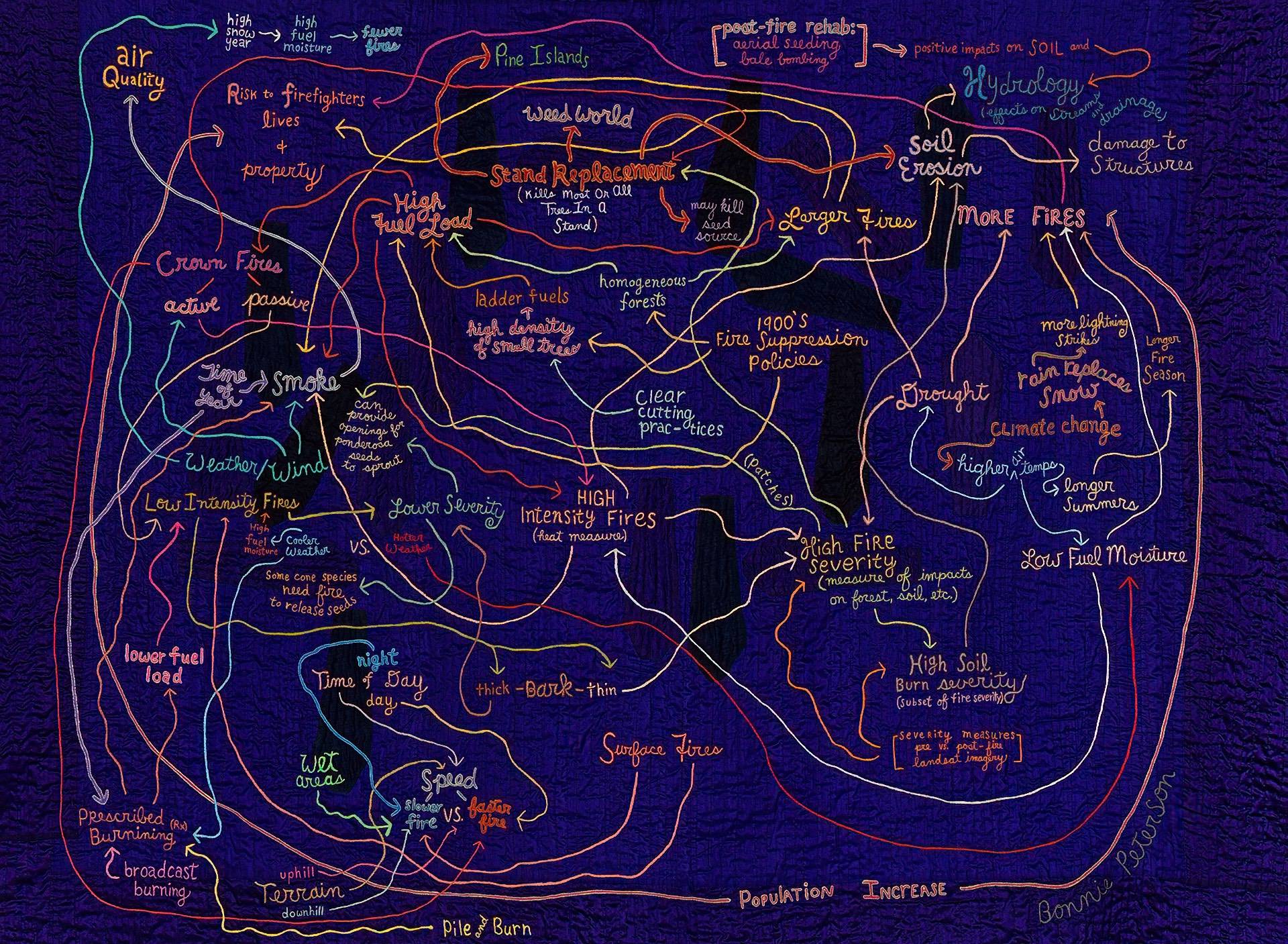

During the boot camp, I saw that my notes contained a mess of arrows amongst a complex network of fire ecology variables. After I returned home and wondered what type of work I would make, my notes gave me the answer.

These arrows and the entanglement of fire attributes and consequences were the basis of On the Nature of Fire. I refined the notes by emailing the scientists until my diagram accurately reflected our workshop.

I embroidered the drawing onto a large deep purple piece of silk. I made the arrows and text more prominent against the deeply coloured background fabric by outlining the text and arrows with further embroidery. It turned out to be quite large with a velvet border.

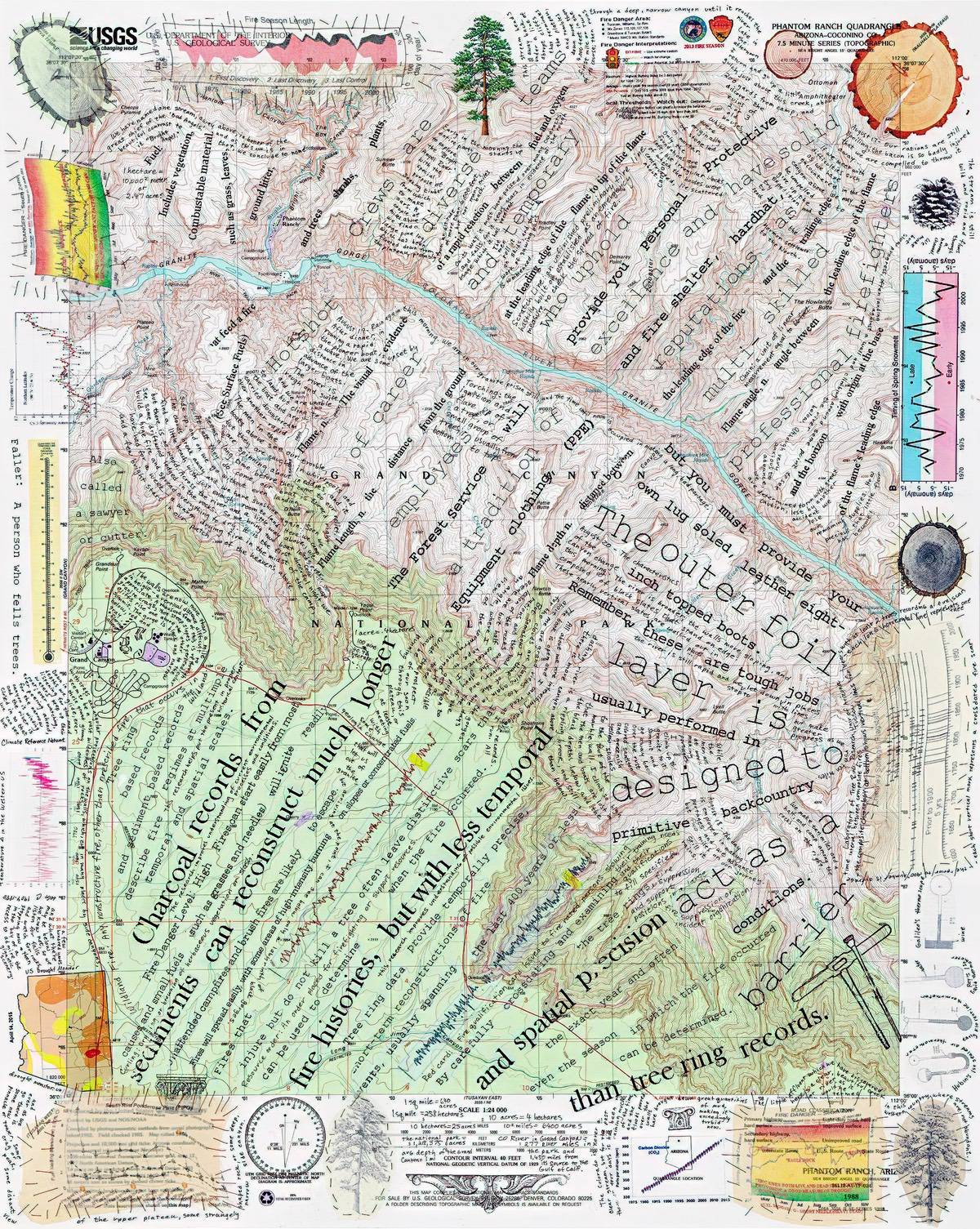

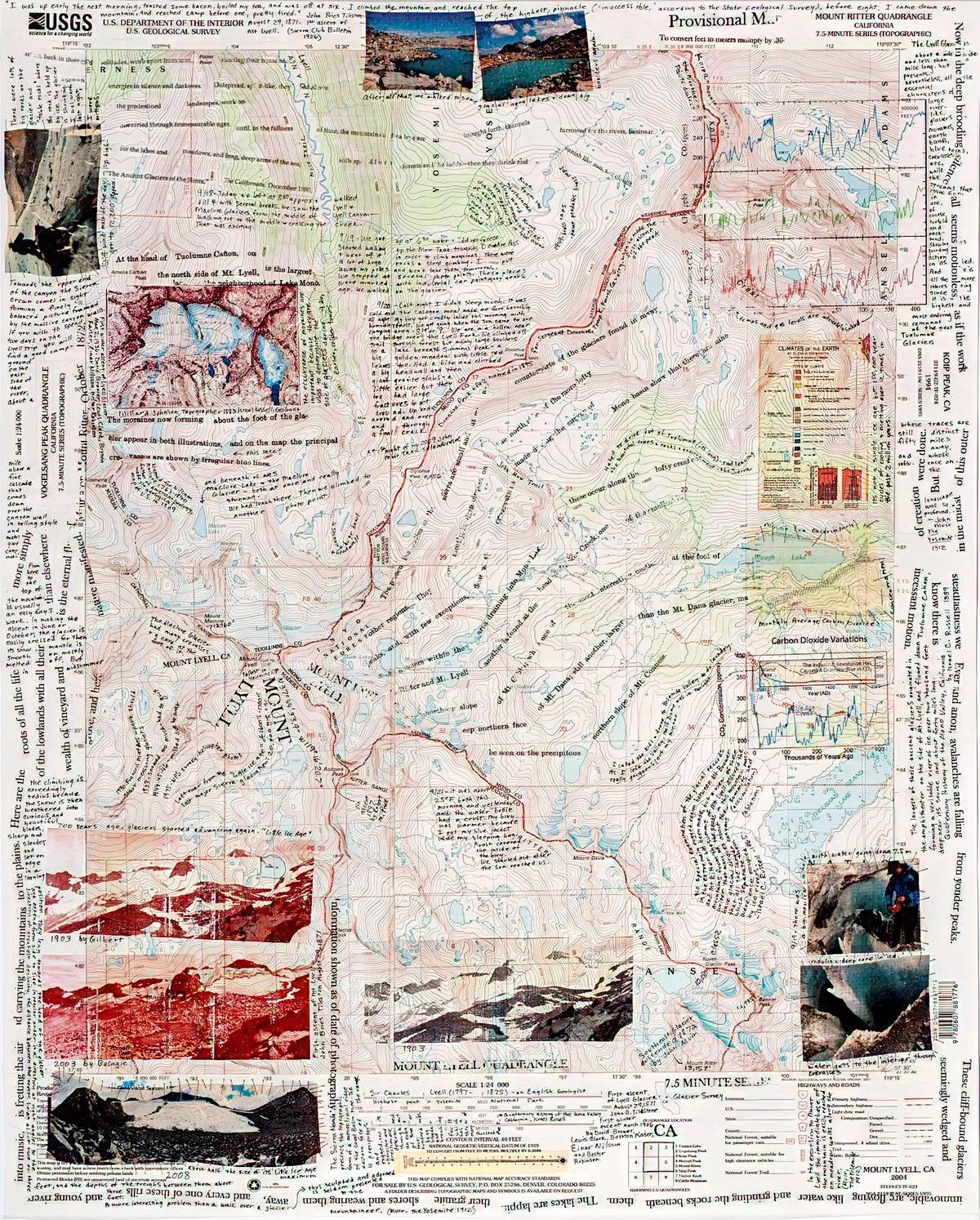

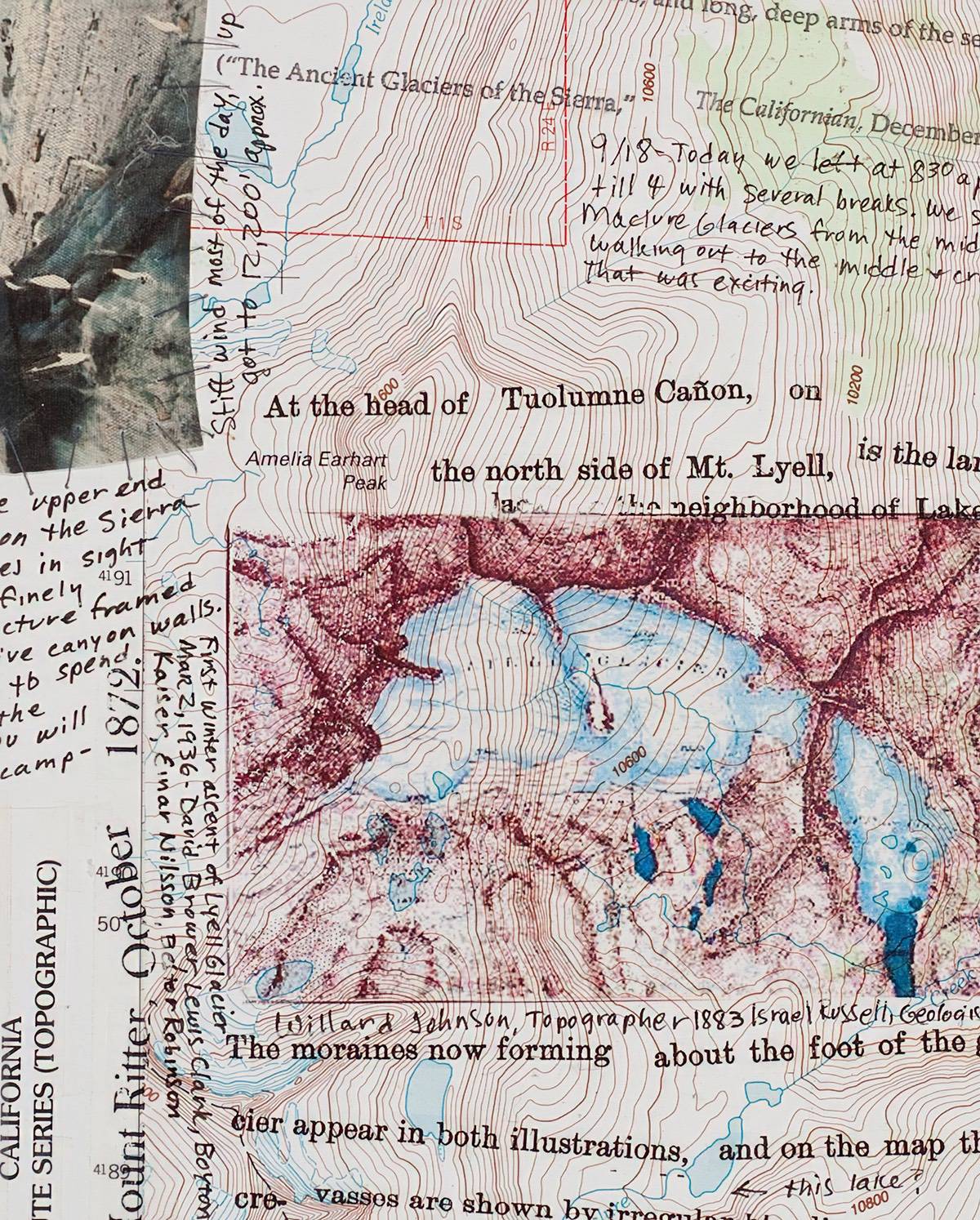

As part of the project, I also made collages on two Grand Canyon topographic maps using text about the labour issues for wildland firefighters, the technical science issues of wildfire and the exploration history of the Grand Canyon.

In Phantom Ranch Quadrangle, I used collage, transfers, pen and stitching on a topographic map. I included text which contains fire terminology, the firefighter’s job description, information about their fire shelters and fire history from tree ring research. There is also text from John Wesley Powell’s Exploration of the Colorado River, 1895.

We had less than a year to complete our work so this large textile, plus two paper maps, had a tight deadline. On my website, I share more detail about my artistic process in engineering this complex artwork.

In nature

I have backpacked in the Sierras since the early 1980s and have a deep interest in the Muir Trail and in Yosemite National Park.

I have a large number of works which integrate the history and scientific measurements of the Lyell Glacier, Hetch Hetchy Reservoir and the John Muir Trail. These works were in the Fresno Art Museum a few years ago and the museum produced a YouTube studio tour video about them.

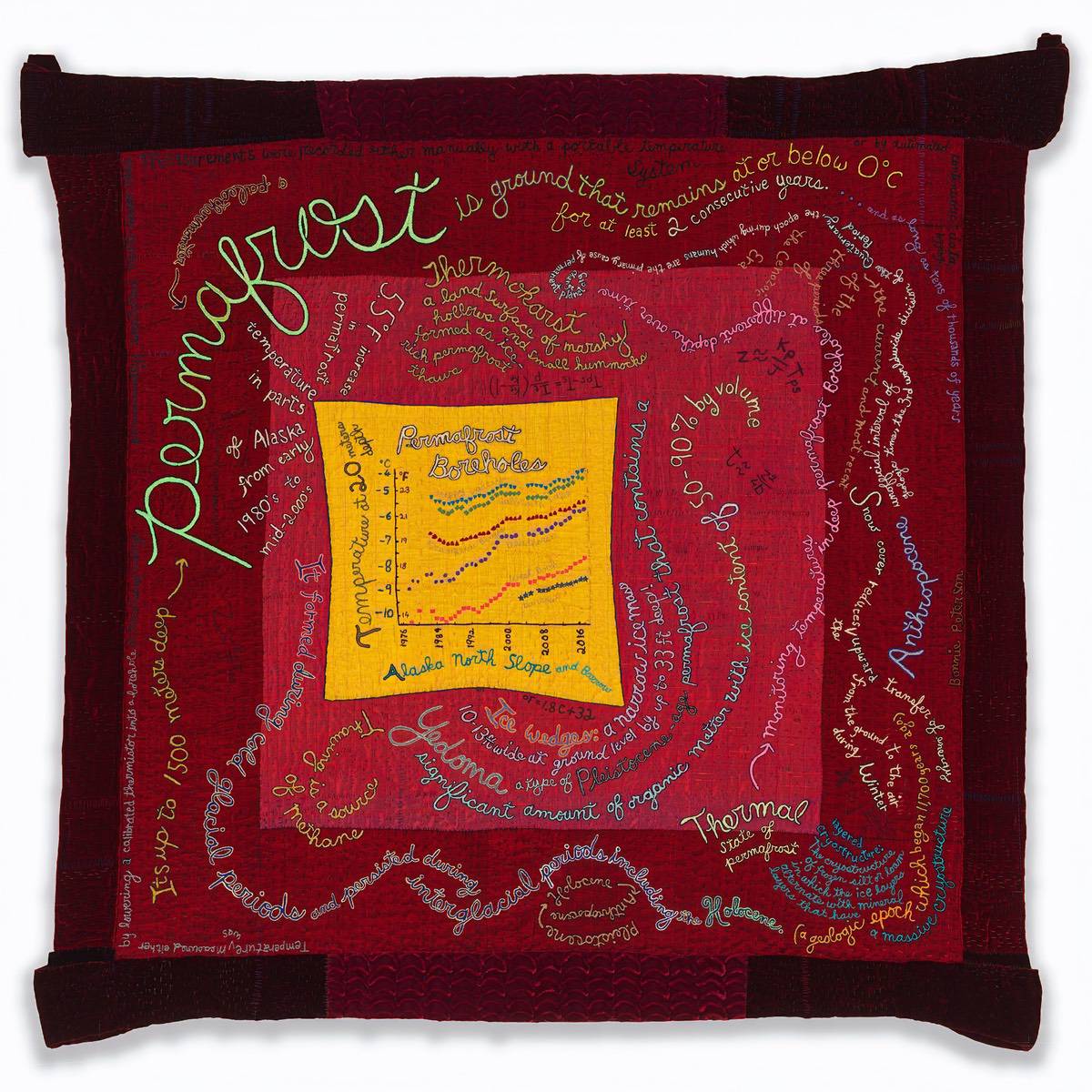

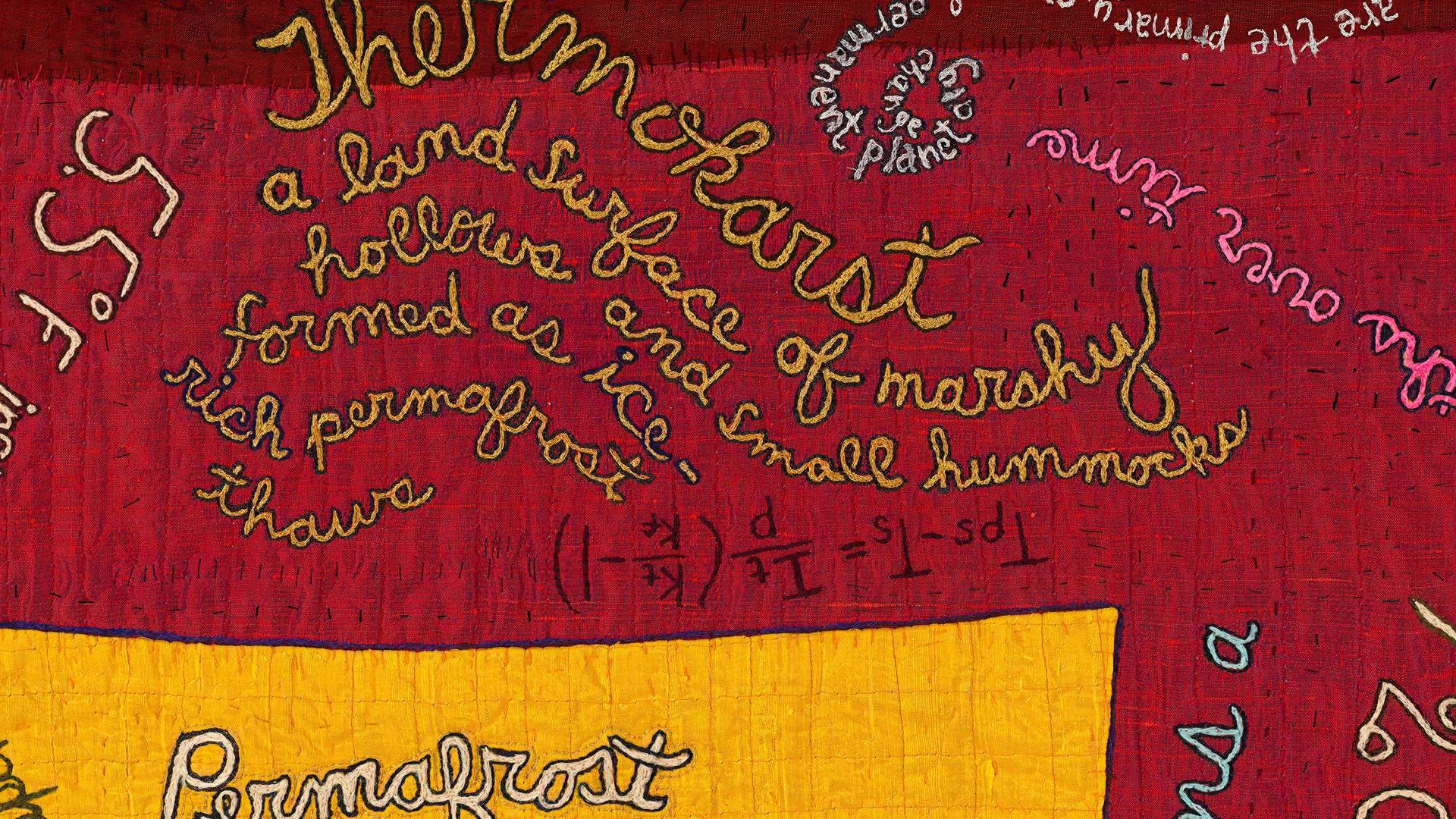

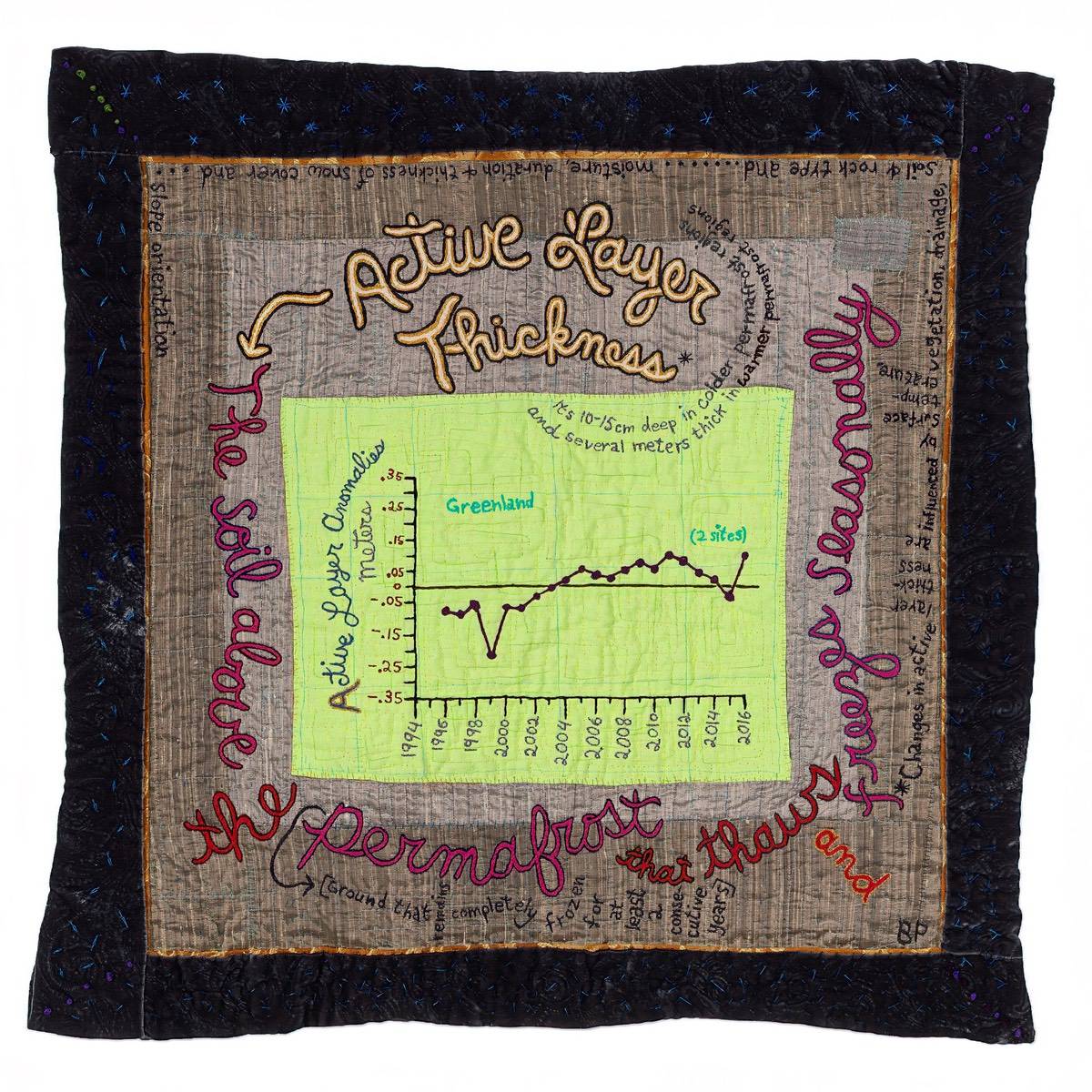

One project was inspired by a backpacking trip to measure the Lyell Glacier with Yosemite geologists. I wanted to make a piece about permafrost for a Chicago show, Geosciences Embroideries. It started out with a graph of the boreholes where permafrost temperatures are measured, using data from the Permafrost Laboratory at the University of Alaska at Fairbanks.

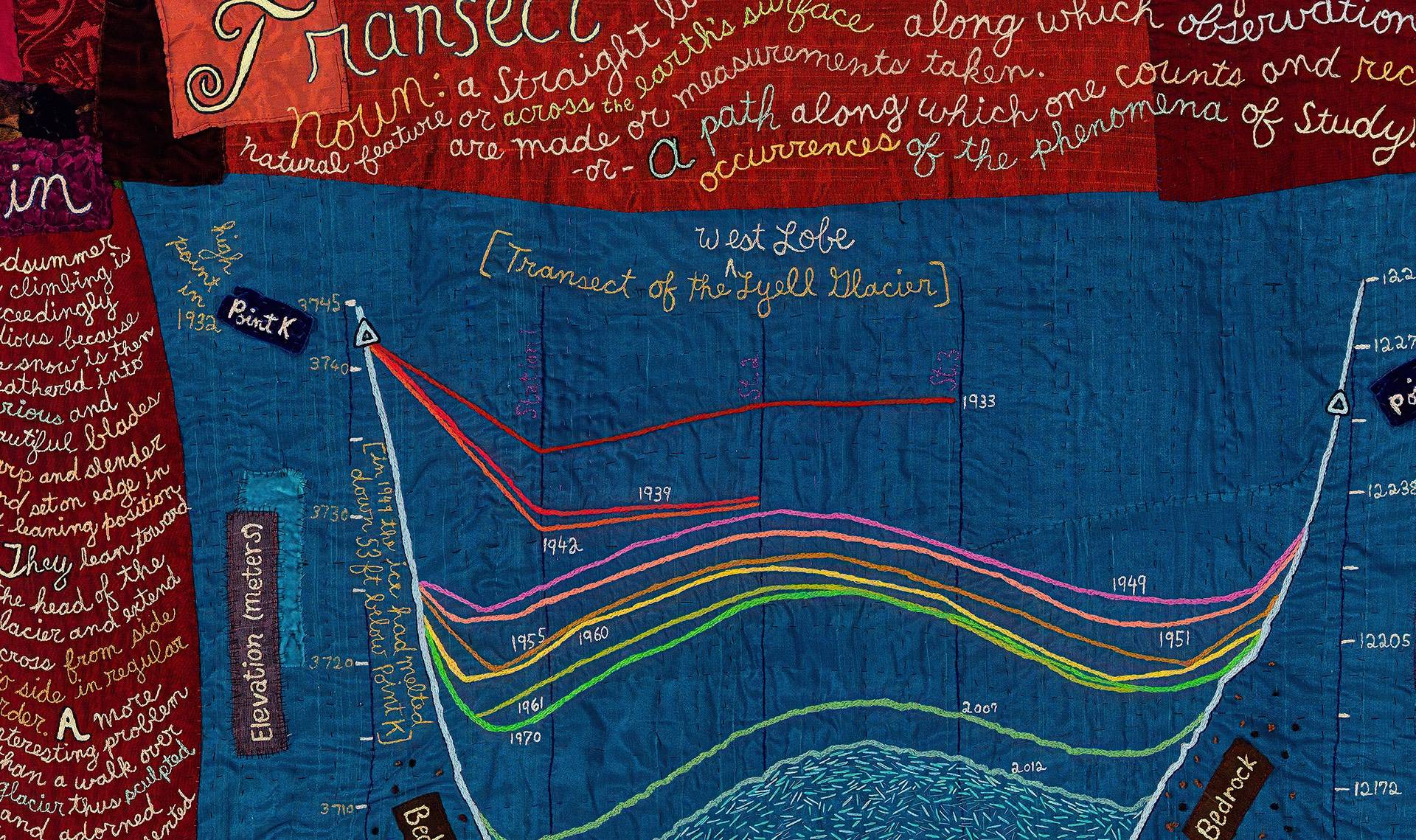

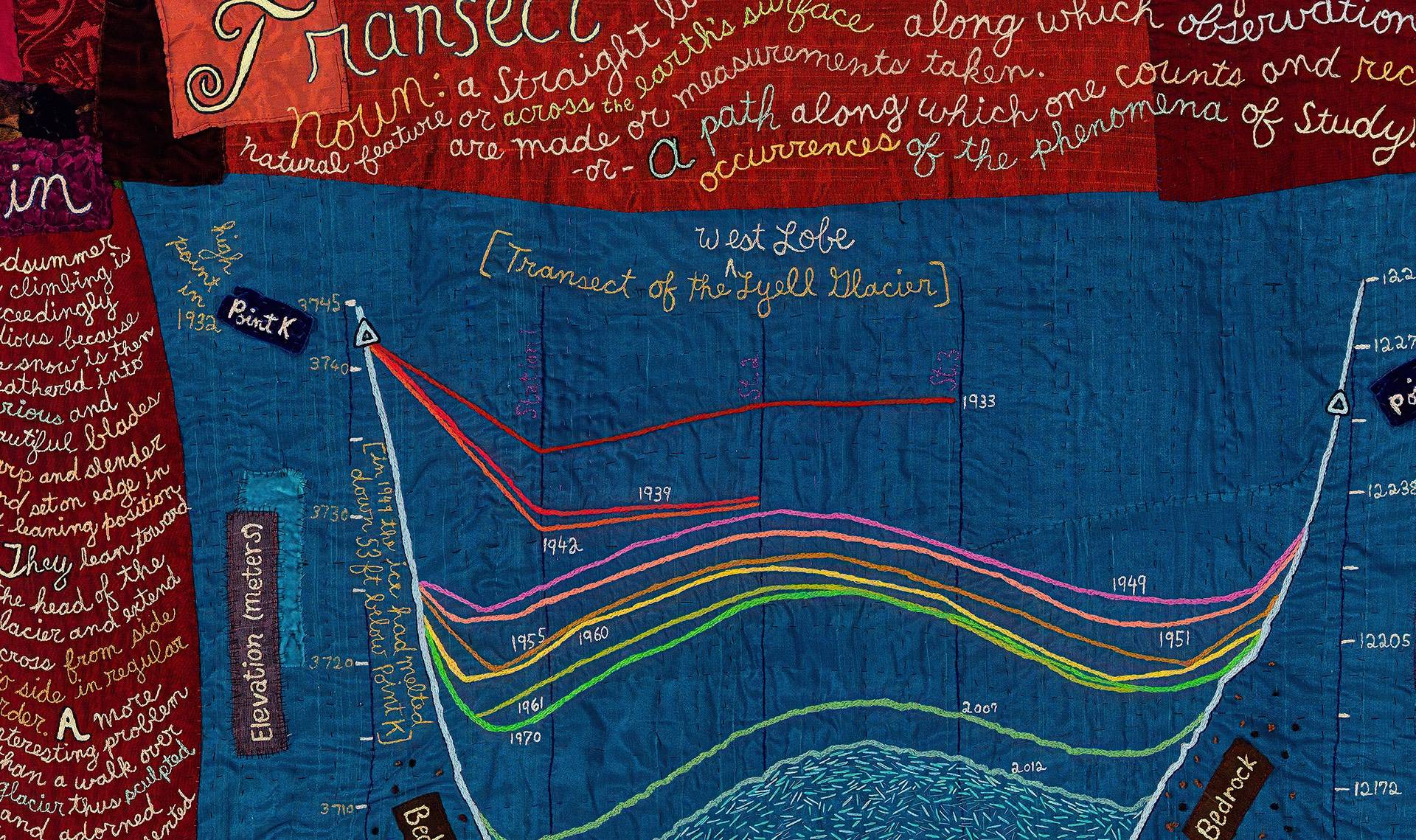

Transect illustrates the Lyell Glacier transect measurements from the 1930s through to 2012; John Boise Tilton’s journal from his 1871 first ascent of Mt Lyell; and John Muir’s description of the Lyell Glacier from 1800.

Permafrost investigations

Permafrost Boreholes includes a graph showing permafrost temperatures at a depth of 20 metres (65ft) in boreholes on Alaska’s North Slope for the past 40 years.

However, I soon discovered that permafrost is more complex than just borehole measurements. There is also the active layer and the issue of permafrost distribution.

This resulted in further artworks, Permafrost Active Layer and Permafrost Distribution. The latter shows a bird’s eye view of arctic permafrost and some of its characteristics. Permafrost thawing also releases carbon dioxide and methane into the atmosphere, causing even greater atmospheric warming.

World view

Although most of my work is two-dimensional, Climate Anomaly Globe gave me an opportunity to work in the round – literally.

In this artwork, more than 100 climate anomalies or deviations for 2017-20 are posted at each respective location around the globe. The 2020 anomalies are on red needles, 2019 are on green needles, 2018 are blue, and 2017 are yellow.

The anomaly data points are from NASA and the World Meteorological Organization. They are printed on over 100 flags and pinned onto a traditional school globe.

For example, one of the red needles that’s planted in the Arctic region states ‘2020 Arctic: 11th smallest maximum sea ice extent on record & 2nd smallest minimum extent on record.’

Finding time

When my kids were small I had National Park residencies. I would go on short backpacking trips with the kids while percolating ideas for artwork to make when I returned home.

The residencies were a great opportunity to balance seeing new parks and working on new issues, at the same time as looking after my family.

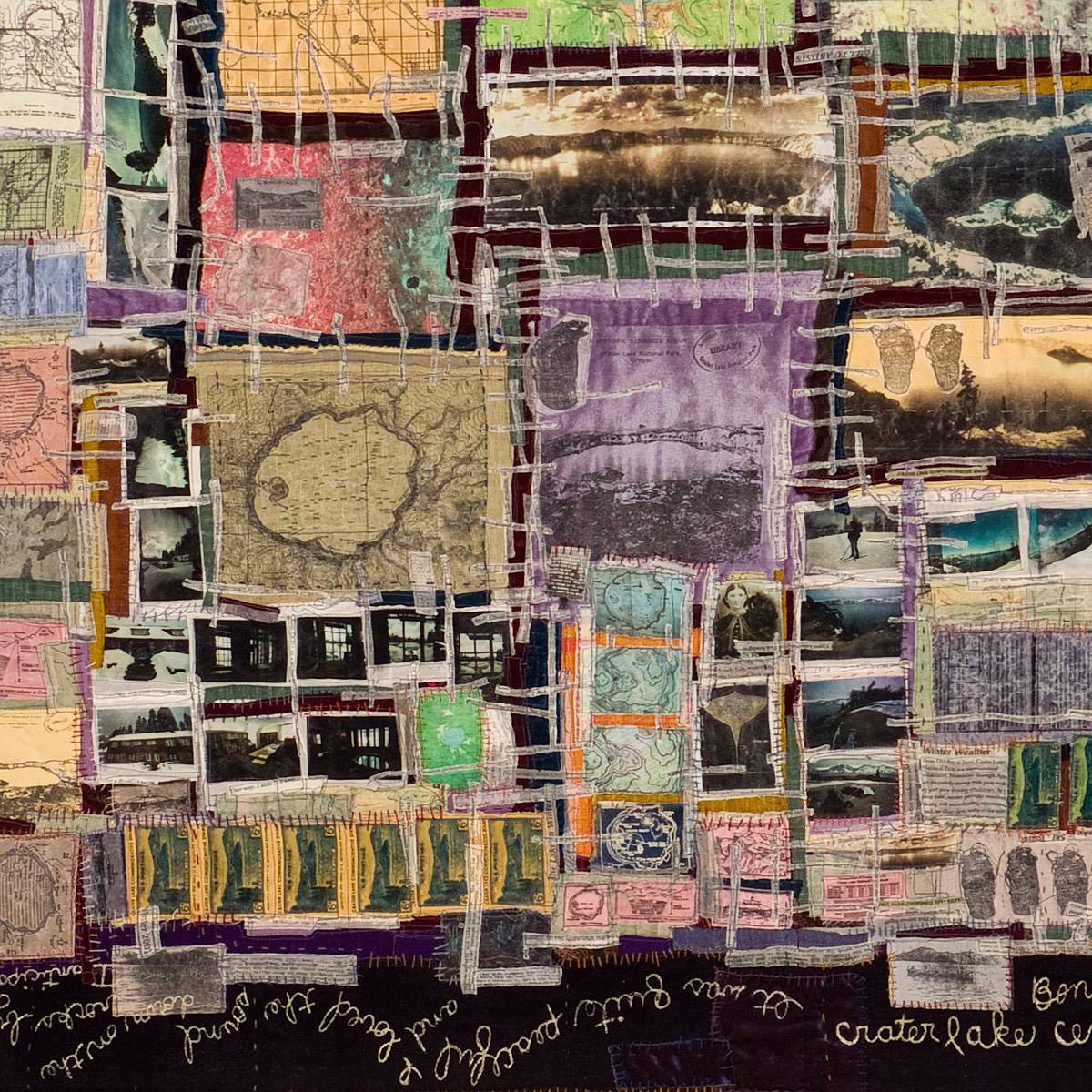

Back in the 1980s, I used standard USGS 7.5-minute topographic maps for orienteering in the backcountry (today, backpackers bring cell phones for navigation). I started to use these maps as the base for a collage of images and text about my wilderness trips.

Some images were transferred to silk and sewn by hand onto the maps and some were ironed directly onto the maps. In Glacier Survey Quadrangle I joined multiple maps together to look as if it were a single map.

When sewing a piece of silk onto a paper map I usually put a small piece of interfacing on the back of the map so that the needle holes do not tear the paper.

Lakeside adventures

I participated in Crater Lake’s Centennial Artist in Residence programme, whose goal was to generate artwork for a centennial exhibition. I requested dates in late March that year because I love to ski.

Crater Lake traditionally receives 12 metres (40ft) of snowfall, which boils down to six metres (20ft) on the ground. They received about a third reduced load that year but there was still enough snow to ski around the lake, a distance of 53km (33 miles).

I had quite an adventure during my backpacking ski trip around the lake, including a broken tent and stove. I made a wall hanging and embroidered the story of my ski trip in the borders with maps and also a large collaged map merging the Crater Lake East and West topographic maps.

One residency will sometimes inform another. At the Lucid Foundation near Point Reyes, California, I started a project where I integrated current and future global temperatures with the consequences of warming.

I used topographic maps as the background and marked them up with global temperature changes and climate consequences. I made a series of enlarged human-sized canvas maps with labyrinths of temperature consequences.

At another residency, I was able to refine these drawings and also a series of embroidered climate graphs. There are about 10 of these graphs and they emerge from oil cans.

‘An artist residency offers a unique source of inspiration – time alone and distance away.’

Bonnie Peterson, Textile artist

Early influences

My mother taught me to sew. When I was in my early teens, she let me choose the fabric so I could sew my own clothes. I still remember my favourite yellow dress.

Back then, sewing clothes wasn’t unusual and a home economics sewing class was part of the girls’ middle school curriculum.

In the 1950s my parents were briefly medical missionaries before settling in Chicago. However, the urge to help people in Africa never left my Dad. I was a junior in high school when our family moved to Kinshasa (now in the Democratic Republic of the Congo).

Dad established an anaesthesia programme at the Lovanium University. Poverty and power imbalances were everywhere, and Zaire (as it was then) was part of the Cold War power balance.

‘The legacy of colonialism contributed to my interest in human rights issues, treaties and war casualties, which has come out in my work throughout the years.’

Bonnie Peterson, Textile artist

I didn’t sew again until I was pregnant and wanted to make maternity clothes and baby clothes. We were living in Tallahassee. I was working part time and also at a traditional quilt shop. There I fell under the spell of the beautiful cotton fabrics.

I joined a quilt guild, and they really encouraged my first wall hanging of the Chicago skyline. My kids were little and I used to furiously work for several hours after they went to bed.

Early works

About 30 years ago a close friend died of breast cancer. This prompted me to make what I call my ‘bra’ quilt. I used de-wired bras, my friend’s poetry and news articles about breast cancer, which I transferred to fabric and integrated with the bras.

My friend’s poems about her experiences with isolation due to the ‘c’ word caused me to call this piece Talk to Me.

I used a dye printing technique with dye paper. Talk to Me didn’t get juried into quilt shows initially so I entered it in the Evanston Art Center’s Vicinity show where they hung it as a sculpture in the middle of the room.

I was surprised that the back was showing with the bobbin threads exposed – it looked a little raw, but no one else cared.

This led me to be unconcerned about the backs of my work being covered or having knots and threads.

Artist’s mindset

My first solo show was at ARC Gallery in Chicago (one of the two women-run ‘co-op’ galleries in Chicago) and I called it Political Art Quilts.

The opening was during a huge Chicago snowstorm, but a few people braved it. I learned how to install, make text signage, and publicise my show.

And while this show was up, I received an Illinois Arts Council Individual Artist Grant. This was a pivotal moment for me.

‘I had no formal education in art.

For the first time, I began to think of myself as an artist and enter my work in juried art shows.’

Bonnie Peterson, Textile artist

Working environment

About 10 years ago, I moved about 400 miles (640 km) north of Chicago, to the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. Houghton is on the south shore of Lake Superior. I work in a home studio.

One side overlooks the woods where I cross-country ski on winter mornings, the other looks out over the street where I ride my bike. I ski from December through March or half of April since we normally get over five metres (200″) of snowfall. However, recent winters have been very short so I have to ride on an indoor bike most of the winter.

Living in a rural area has been a big adjustment after living in the city, and having the easy friendships, nearby art communities, monthly openings and the variety of art venues on your doorstep. I miss all of that.

‘I use every opportunity to see art exhibitions when I’m travelling, and I try to connect with other communities of artists.’

Bonnie Peterson, Textile artist

Guiding principles

The twists and turns in my work have always eluded my ability to predict a direction, and that’s what makes life interesting.

I look at as much art as possible, whether or not it has textile content. I use travel as a way to expand my geographic reach and exposure to more art. I recently visited Japan and that’s given me lots of inspiration.

It’s good to seek out an artist community. Look for studio tours and speak with the artists. When I was starting out exhibiting my work I belonged to a critique group of fibre artists. I was inspired to make work for the monthly meeting deadline. The structure of critical sharing was also helpful.

I encourage you to follow your intellectual curiosity. I have always been fond of maths, data and graphs and so I combine that with my interest in climate issues. My first subjects were prompted by my interest in the Gulf War and family issues – marriage, children and divorce. I am deeply committed to environmental data, policy and justice issues and I expect to continue with this theme.

6 comments

Kathy Weaver

Bonnie is a modest and quiet force. Her work is even more amazing when you see it in person. She has pursued being an artiast activist with a steady vision and dedication throughout her career. It is always inspiring to see her work and hear her tlk about her experiences. Thank you for a great article.

Shannon Tucker

Love this!

Cornelia

What a fascinating way of expressing all the climatic changes around us! Thank you for this inspiring article.

Congratulations on your work, Bonnie.

Fátima Rodríguez de Peñaranda

Precioso trabajo. Beautiful work. Mairvelleuse le travail.

Annika

Dear Bonnie, I’m glad ‘cose I can see your fantastic works, your art, all the maps, (I like maps) and all beautiful things. I would say for you a big CONGRATULATION! Best wishes – Annika

Julie Collishaw

Great to see your body of work in this field. Thank you for sharing the details of your process