Caroline Bartlett could be described as a “historian in stitch.” Her passion for exploring the historical, social and cultural associations of textiles result in art installations that take your breath away.

Her work entitled “Stilled” is a prime example. As you’ll discover in this article, every material choice—from threads to hoops to fabrics—has a significant historical connection to the space in which the work was installed.

In the newest article from our From Conception to Creation series, you’ll also discover how Caroline breaks traditional boundaries of how textile art is displayed and viewed. Her works are not neatly framed and hung on a wall. Instead, Caroline takes over entire spaces and literally suspends her work in ways that engage viewers like no other.

Examples of Caroline’s work can be seen in various public, corporate and private collections, including those of the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Crafts Council. Her work has also appeared in over 35 national and international exhibitions since 2000.

Caroline has received numerous awards throughout her career, and she is a member of Crafts Council Index of Selected Makers and Contemporary Applied Arts, 62 Group.

Name of piece: Stilled

Year of piece: 2013

Materials used: Porcelain, embroidery hoops, cotton thread, woollen cloth, miscellaneous fabrics

Techniques used: Stitch, dying, imprinting porcelain

Size of piece: 7.5 x 1.58 x 2m

Connecting to the past through thread and fabric

TextileArtist.org: How did the idea for the piece come about? What was your inspiration?

“Stilled” was made in response to Salts Mill, Saltaire’s proposal to take part in an exhibition curated by Lesley Miller called “Cloth and Memory 2.” The site itself—its history and context—inspired the work.

The exhibition was to be shown in the old spinning hall, once the largest room in the world, that is now silenced, emptied, and stilled. It used to be a space of noise, activity, and industrial production.

My original thoughts were to make big work for such a monumental space, but my responses to the site made me think about cloth as a silent witness to the intimacies of lives lived out here in a day-to-day routine of repetitious activity. I thought about human interactions amongst the clatter of machinery.

Thread residues remain inserted into cracks and cling to metal beams, and the walls themselves seem to seep cloth. So, I imagined wool, pushing through the built outer skin of the building leaking into it with the smells and oils of its production.

There is a strong sense of presence and absence of a bygone era of industrial manufacture in which industries, such as textile and ceramics, were so central. Salts Mill speaks of transformation and change as the mill changes its role in the community.

So, I also began to think of the building in terms of skin, bone, and membrane. A layered dermis. And of the webs and cycles of textile processes and human relationships both extending from and contained within it.

Touch, rhythm, and repetitious movement.

What research did you do before you started to make?

Initial research involved site visits to take photographs and explore the vicinity. I then extensively researched the mill’s past and present place in the community. This included researching mill closures in the area and their name changes: Lister Mill (1873-1992), Salts Mill (1851-1986), and Martin Mills (1931-present).

I also explored the names of different types of woollen fabric represented by Yorkshire Mills at the Great Exhibition of 1851. Many of these we no longer recognise, and the names are lost from our vocabulary.

Finally, I visited archives and museums, and I used the internet before I began to find my direction and could produce a proposal to put to the selection panel.

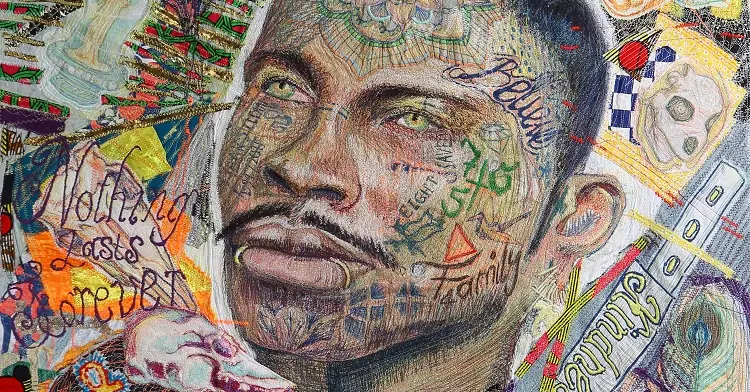

Framed by the immensity and silence of the surrounding architectural space, I proposed to make a work of quiet intensity which reflects author Pennina Barnett’s ideas of “the texture of the intimate” and “a space of close vision, the curl of a hair, the twist of a thread, the crease of a cloth” described in her book “Folds, Fragments, Surfaces: Towards a Poetics of Cloth.”

Through this close viewing of the “unseen,” I felt that whilst alluding to cloth and clothing, the work should draw on ideas of membranes and supporting structures, ephemerality and the cyclical nature of change.

I then started to print from, draw, and scan articles of clothing and fragments of cloth.

It’s the details that create meaning

Was there any other preparatory work?

Preparatory work also involved the testing of ideas, so maquettes—small models—were made along with drawings to indicate how the pieces might work in the space.

The original idea was to hang the piece in the main space, but as ideas progressed and thoughts turned to sightlines for the overall exhibition, I began to think of a more intimate placement and moved my thinking to a large alcove.

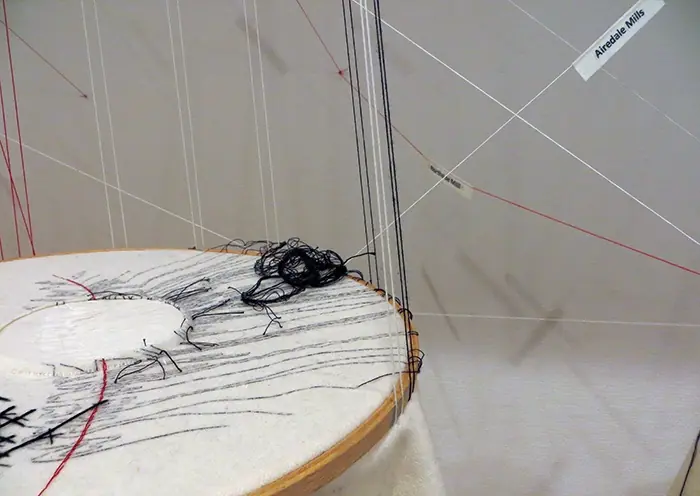

This offered a perfect solution but came with restrictions of having to hang off a metal beam. So, the hanging mechanism had to be resolved and become part of the piece.

What materials were used in the creation of the piece? How did you select them? Where did you source them?

Where possible, materials were selected firstly for their resonance, connection and aesthetic. Then their practical support was considered.

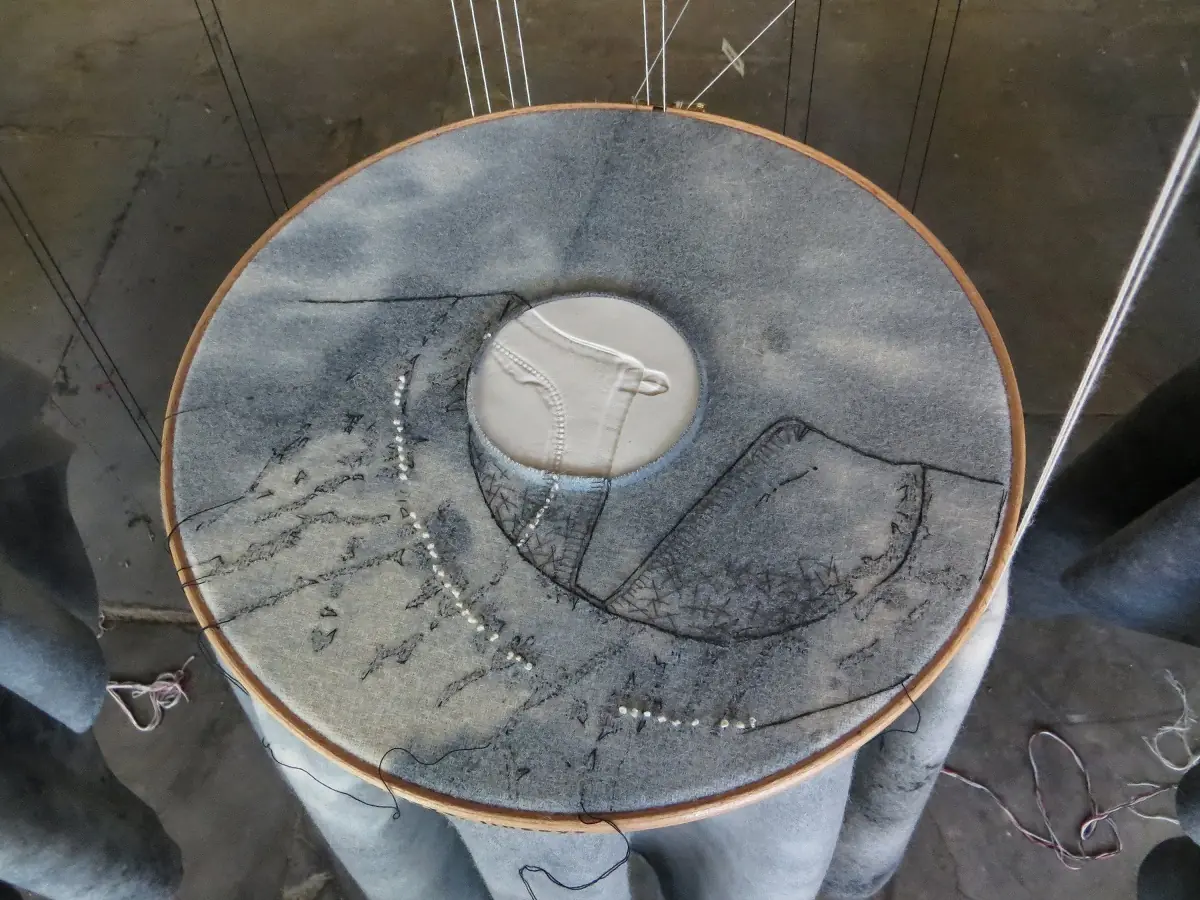

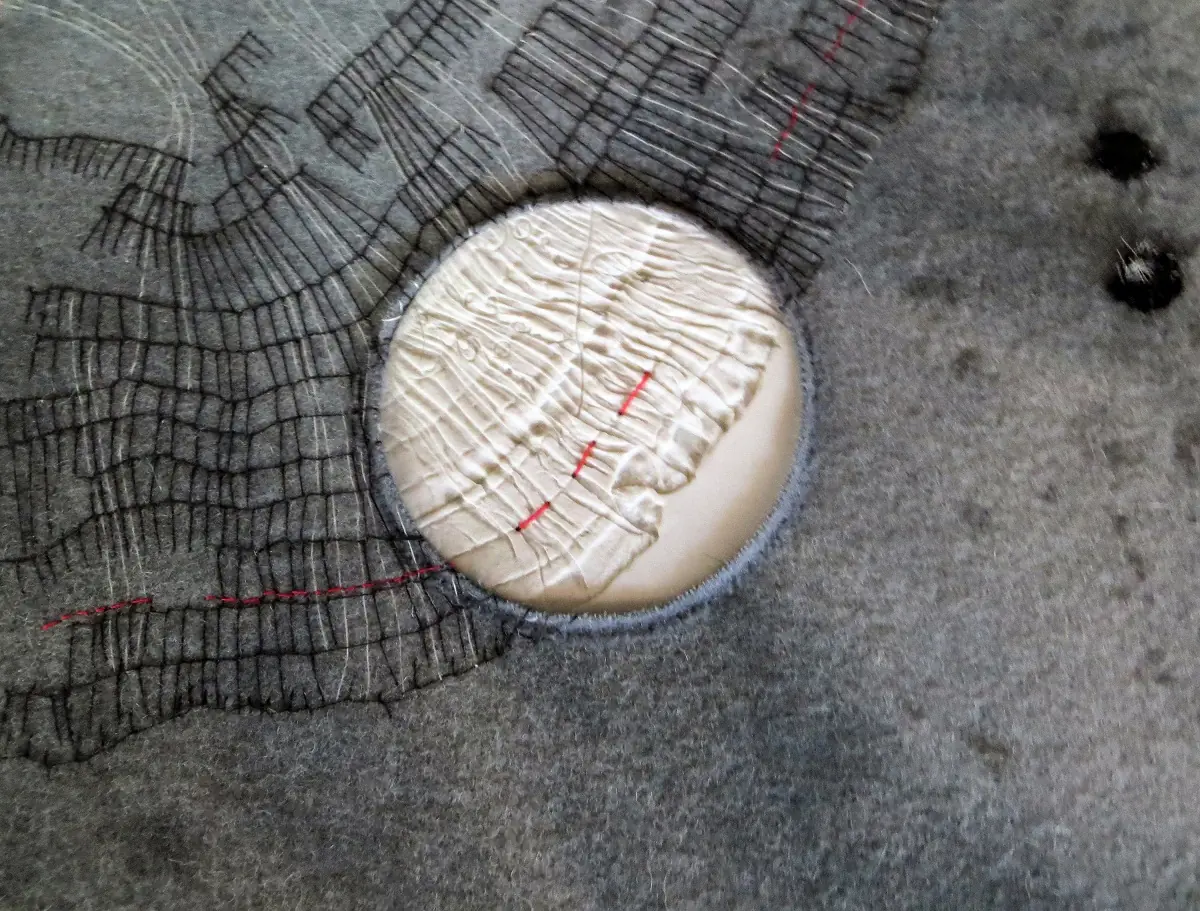

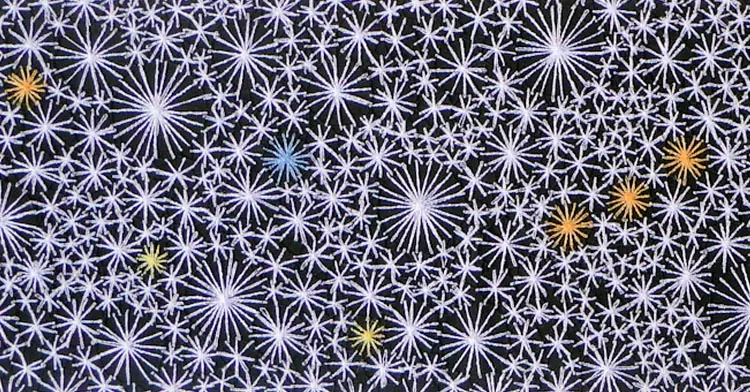

The embroidery hoops are stretched with woollen cloth from Bradford, into which a small porcelain roundel is mounted that is imprinted with an impression taken from a section of cloth (folded, creased, crumpled) or clothing (pinafore, apron, shawl).

A stitched drawing, just under the skin of the cloth, spreads out from the porcelain impression continuing the imagery. These glimpsed “drawings” range from the more descriptive in interpretation to the more abstract. But the clues were to be found in the porcelain impression.

The fabric draped from the hoops was marked as though it was soaking up a history of spillages, stains and oils from the floor. There are small moments of intensive stitching, threads and other cloths pushing through.

In one of these hooped drapes, the fabric was taken from a sari and is a memorial to the workers who died in the collapsed garment factory building in Dhaka whilst I was working on the piece.

A network of threads ties the work physically to the building, each carrying fabric labels referencing the names of mills, dye works, or weaving sheds in a geographical trajectory from Shipley to Bradford. These are sourced from an inventory supplied by Yorkshire Industrial Heritage.

Whilst some of these buildings have been demolished, others have retained manufacturing connections with their industrial past. Others have changed their use, part of a cycle of degeneration and regeneration such as Salts Mill.

The outer edges of the wooden hoops carry the names of different types of woollen cloth or wool mixed with other fibres.

What equipment did you use in the creation of the piece and how was it used?

I was lucky enough to have found a ceramicist who did commission firings. But otherwise, the piece incorporated hand processes of dyeing and stitching with the occasional use of an embellisher to incorporate threads and other fabric fragments.

The stitching was partly mediated through print and digital processes in which the clothing was scanned and redrawn. And my transfer press came into its own for printing the labels referring to the textile works on a 5-mile trajectory from the mill to Bradford.

Experimentation leads the way

Take us through the creation of the piece stage by stage

The piece was created in stages to meet the exhibition schedule.

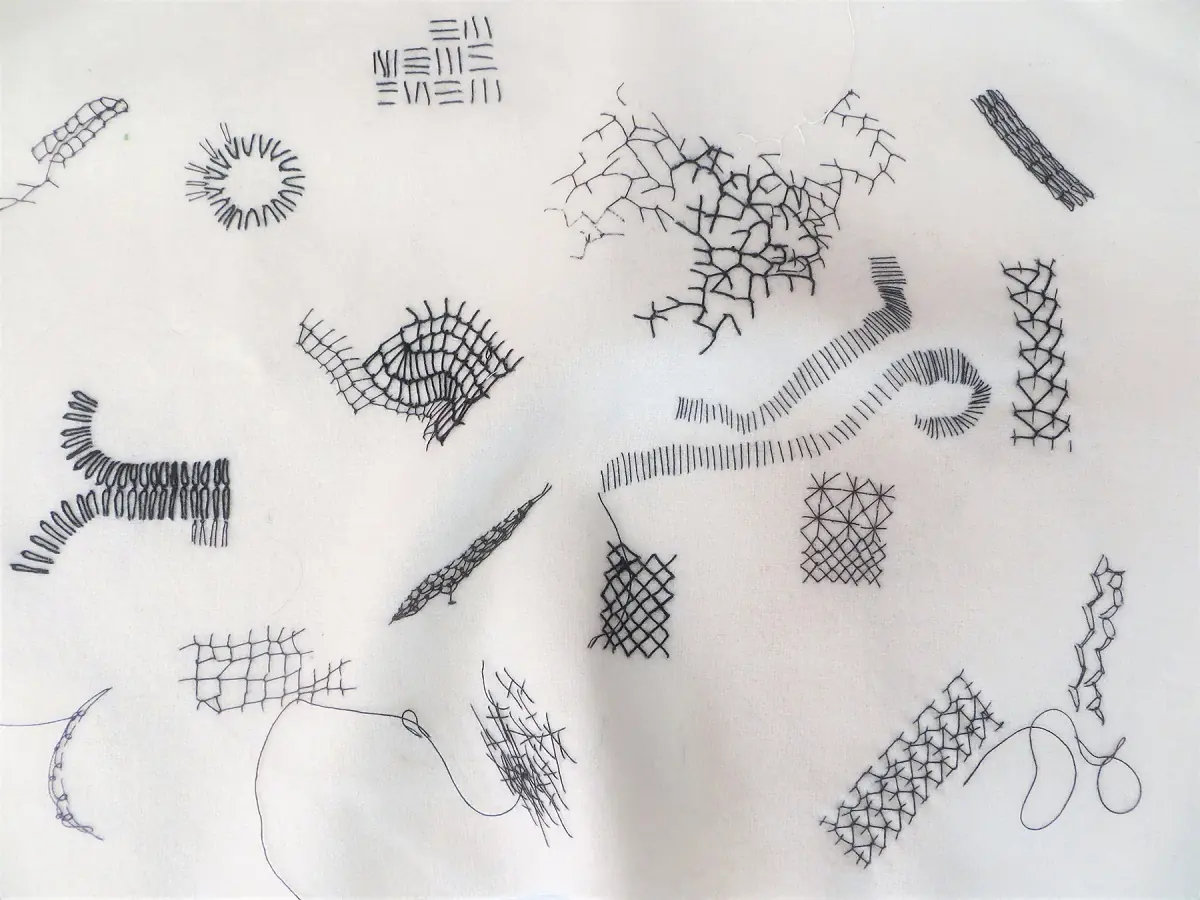

The first stage involved a general first look and investigation of content and theme, treatments and contexts. This entailed both technical and aesthetic explorations, dead ends, and conclusions through sketchbook work, drawings, and sampling.

Then experiments were made with printing and drawing from clothing, as well as digital scanning to provide stitching information.

Samples were made of imprinted porcelain, and as a new technique for me, processes had to be refined. A lot of fragments were created!

Different woollen fabrics were also tested to find the right weight and which fabric best suited my stitch and dye techniques.

Then appropriate texts related to Salts Mill and the context of cloth production were identified and printed on the hoops. And the labels were printed on the transfer press and set on threads wound ready for installation.

Successful experiments were ultimately chosen and actual pieces made up.

And then after all that, systems of display and methods of tensioning and inserting threads into the wall were tested and finalised.

Final installation took place over a 3-day period.

What journey has the piece been on since its creation?

Since the Salts Mill showing, “Stilled” has been exhibited at the Rijswijk Textile Biennial in 2015. I found it interesting to see the impact on the work being stripped of its context and shown in a pristine gallery space.

What I most like about this piece was how it drew people in to look more closely, and as they did, the passage of air made the piece move ever so slightly. Like a breath passing through.

For more information visit carolinebartlett.weebly.com

How have you broken boundaries in displaying your own textile art? Let us know by leaving your comments below!

1 comment

henrike Gootjes

this is amazing!

to use history, tactility, craftsmanship! and all of such high quality! I love it!

I am currently doing a master called the International Master Artist Educator. We research and find ways to use the artistic proces to make change and create new narratives. This to me is such a beautiful example of this.

Thanks for writing about this!