After a career in business, training and coaching, Claire Benn returned to her first love – textiles. Twenty-five years on, she is one of the UK’s leading mixed media and textile artists.

Based in Surrey, UK, Claire has worked as an author, curator and educator in art textiles. She has published a series of books about her specialist form of textile art and runs workshops in the UK, Germany, Canada and the USA.

Claire is inspired by nature, in particular by the desolate, and yet highly textured, landscapes of the Arctic, Alaska and New Mexico – places where she enters an experience of emptiness and timelessness, evoking thoughts and feelings that she interprets into her textile art. Over the years her practice has become quieter and slower – so much so that her social media accounts and blog are entitled ‘Her Quiet Materials’.

In this article, we learn more about Claire’s inspiration and motivation and how her journey with textiles has taken her to a more peaceful and meditative pace of both life and work.

Exploring surface design

TextileArtist.org: What initially attracted you to textiles as a medium? How was your imagination captured?

Claire Benn: I re-engaged with textiles in 1994 in response to seeing a Mennonite quilt in Canada. I was inspired by the combination of form and function and simply wanted to have a go. Anni Albers says “how do we choose our specific material or means of communication? “Accidentally”. Something speaks to us, a sound, a touch, a hardness or softness, it catches us and asks to be formed”. Quite simply, textiles caught me.

After making several quilts using traditional techniques but to my own designs (what might be called ‘Modern Quilting today), in 1996 I encountered hand-dyed cloth and learnt the basics from Leslie Morgan. That same year we’d moved the family out of London and I was able to commandeer an outbuilding as a wet studio. Being self-employed enabled me to control my diary and dedicate myself to a regular studio practice. I stopped making quilts and started concentrating on making a single piece of cloth work for me visually. In 2002 Leslie and I launched ‘Committed to Cloth’. Another outbuilding was converted into a second wet studio, the dining room was claimed as the ‘stitching room’ and we were off. I do believe that my background in business, training and coaching enabled us to get a fast start, as teaching and marketing skills are transferable.

What or who were your early influences and how has your life/upbringing influenced your work?

My father engaged me in art from an early age and I spent happy hours drawing and painting. Like most people who engage with textiles, my paternal grandmother started me off with small projects such as samplers and needle cases. I made a nightdress that would have fitted an elephant, so that was the end of any attempts at clothing. Not being academically minded, I left sixth-form at seventeen and started work and any form of art was sidelined in the quest for financial self-sufficiency and independence, culminating in work as a self-employed training consultant.

What was your route to becoming an artist?

Learning about and exploring surface design techniques took me down the road of art. Spending time at a sewing machine didn’t do it for me and as such, making clothes or functional items held no appeal (although I do occasionally make a functional quilt). Leslie encouraged me down the art route, as did Nancy Crow and Jane Dunnewold. Exploration time in my studio taught me that before I could get to the ‘creation’ part – the realisation of ideas and inspirations – I had to master both the materials and the making process. I had to learn the craft. Once I’d achieved that, I’d be free to use my materials in any way I wanted, free to transform my inspirations into artworks. And finally, with due diligence paid to composition, I’d get to the stage of artist.

It took me 10 years of practise to establish a practice. To get to a point where I felt I knew what made a good composition and to settle on what I wanted my work to communicate – what sensibilities I wanted my work to stimulate in the viewer.

The artist Agnes Martin became a guiding light for me. The stillness, emptiness and simplicity of her work resonated, as did her writings. One statement galvanised me; “you must discover the art work that you like and your emotional response to it. You must especially know the response that you make to your own work. It is in this way that you discover your direction and the truth about yourself”.

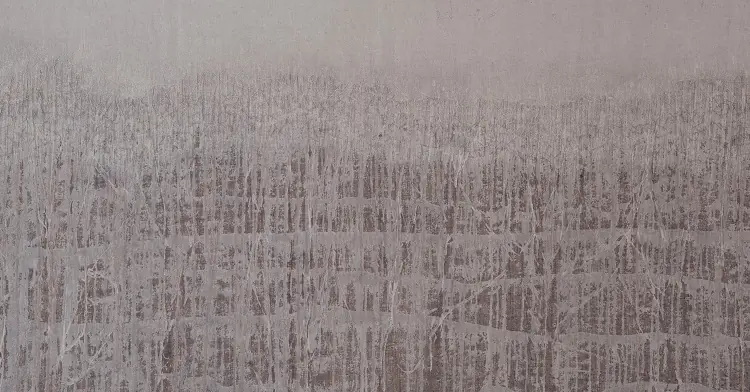

I set out to clarify my emotional response to my favourite art and re-examined the works of Mark Rothko, Agnes Martin, Gerhard Richter, Rebecca Salter, Howard Hodgkin, Antony Gormley and Dorothy Caldwell. I then considered the remote environments I love such as the Arctic, Alaska, and the desert landscapes of New Mexico. I discovered that how I felt when looking at my favourite art was the same as how I felt out in a remote landscape. For me, it’s all about sensing space. Getting lost in the ‘picture’. At peace. At rest. Absorbed. Alone.

Slow stitching is honouring time

Tell us about your process from conception to creation

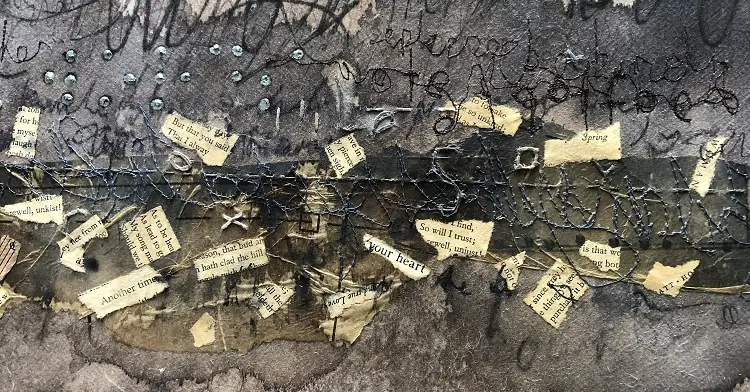

The challenge was to then visually express what I felt in those landscapes – translate those feelings into work of my own. That meant restricting my tools, my media, my palette and my process – simplify, simplify, simplify.

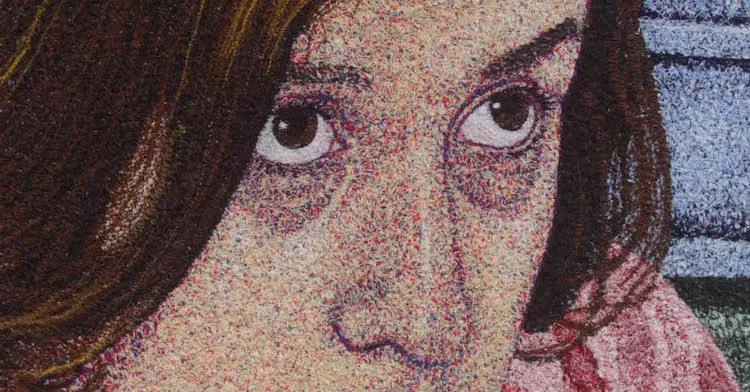

My key starting point is simply one of looking, allowing the silence and stillness of place to enter. With looking comes seeing – both the (apparently) empty space and the fullness of detail within it; textures, colours, tones, lines, forms. I also like to write – not in the sense of a journal – more of a simple record of my thoughts and feelings. No sketchbooks as such, just a few roughly drawn references of what I see and respond to. A few photographs. Enough to serve as a reminder of colour and ‘assist’ the drawings.

I place my trust in memory rather than recorded images as my aim for my art is to stimulate the same sensibilities I experienced when in the landscape. I do not wish to reproduce the landscape itself, but what I feel and experience. I do print a few photographs when I start on a new body of work but often chop them up, leaving only ‘slivers’ of colour, texture, line or form. They get pinned up for a while – often in the wrong orientation – but get taken down fairly quickly.

I decide on my size, format and initial background colour and just start. I rarely sample small as I find that to truly understand a composition, I have to work to size. A great deal of time is spent looking and considering the work as it evolves. I can’t honestly say what I think about when I consider a new work-in-progress, I simply look and let the thoughts come. I make a few notes, perhaps do the odd sketch, make a decision as to the next steps and get on with it.

I think that the discipline of developing a solid practice also develops an instinct and trust that whatever is being done next needs to be done in order to move the work forward. At times those instincts fail – the idea isn’t realised – but I do know that there is no such thing as a failure – as long as the lesson is extracted and further learning takes place. Sure, there’s always an element of risk but without risk, we won’t move forward and if we don’t move forward, the work doesn’t get made. I feel it’s important to appreciate that all artists create more work than they exhibit, and a good bonfire is no bad thing!

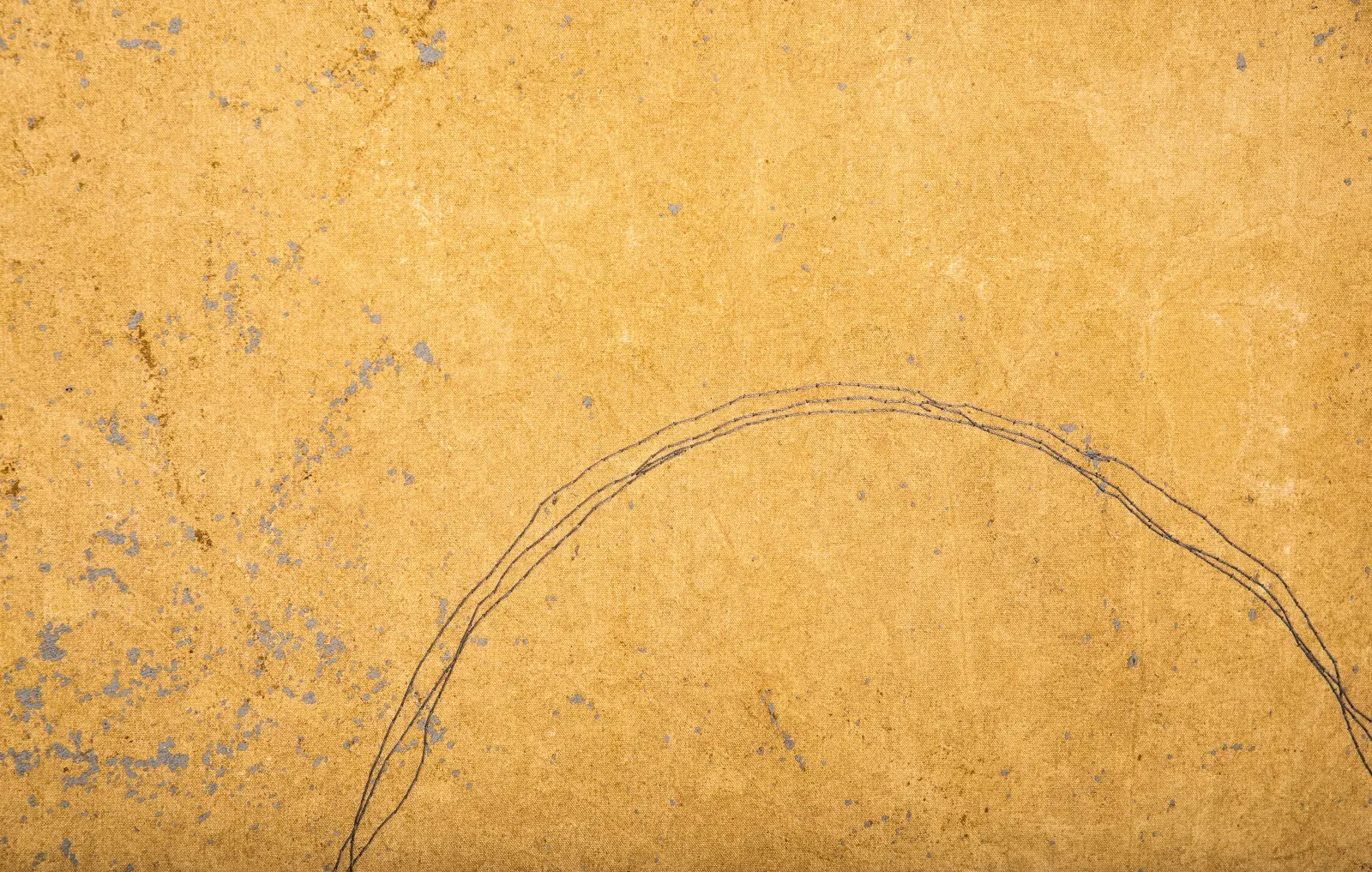

Tell us a bit about your chosen techniques and how you use them

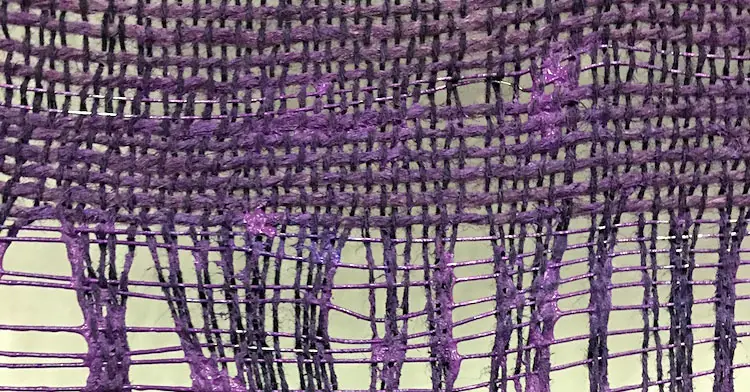

I used many surface design techniques in my early work but haven’t now used a silk screen or thermofax screen for many years, preferring to work with tools that give me a greater sense of my hand. I’ve also moved away from using fibre reactive dyes, preferring to use raw earth pigments for my landscape works as they connect me back to the land and have a definite literal texture. I bind them into a mix of acrylic medium and water and use a (sort of) mono printing process to lay down the background. I work on the floor or on sheet plastic, working from the back which means I’m working blind. Whilst I can control colour and value, I can’t control everything about the end result. This gives me a sense of discovery when – once dry – I pull the cloth up.

‘Traditional’ mono printing techniques are key techniques for me, although I don’t use a glass plate, preferring to work on plastic and take the cloth to it or take painted strips of plastic to the cloth. This allows me to a) work directly with my hand (with or without a tool in it), and b) assess the look of what I’m laying down before it gets on to the cloth. Cloth is absorbent but plastic isn’t. I can move colours and values around on plastic before I commit, which I can’t do working directly on cloth. Scrapers, foam rollers, squeeze bottles, paint pads and brushes are also key tools for building up layers and developing the work.

More often than not, hand stitch is involved; before, during and after painting. It can be scary to layer paint on top of something that’s taken days or weeks to stitch, but I feel the encrustation of paint on stitch helps me to convey a sense of earth, rock, stone or other natural elements. Paint on stitch also somehow integrates the thread into the work and if I want, need or choose to, I can sand the paint back to generate more texture.

The ‘wet work’ aspect of what I do is relatively quick in relation to my other key process; that of hand stitch. I have developed a love of slow process as I get older. It’s extraordinarily calming and a way of honouring time, and I now fully accept that making good work takes time. Gandhi said, “There is more to time than increasing its speed”.

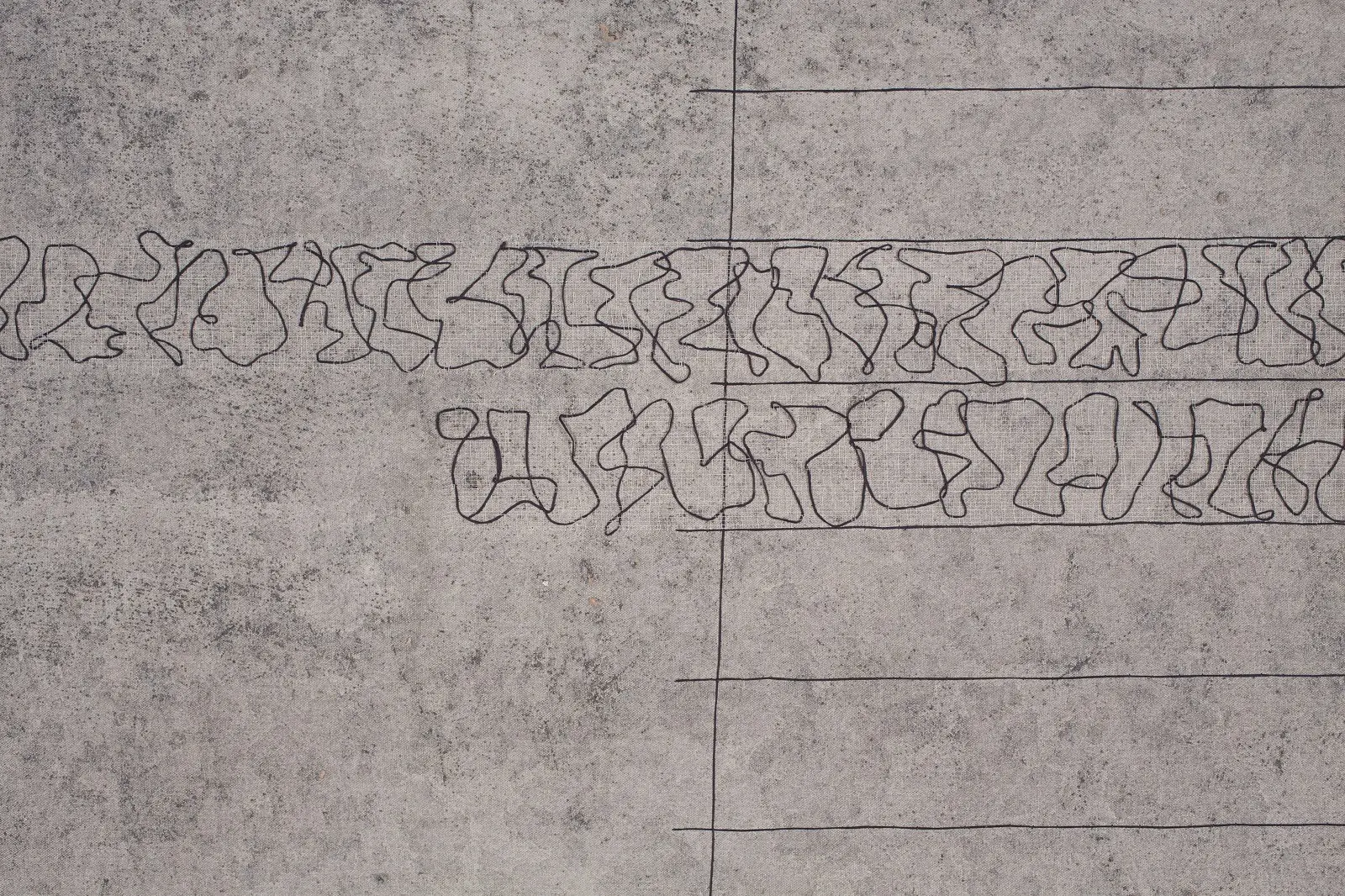

I re-engaged with hand stitch in 2013, whilst on an Ayurvedic retreat in India. Hand stitch is an exploration of stillness and silence, and most definitely a kind of meditation due to the repetition involved. Draw out the thread. Snip it off. Thread the needle. Makes the stitches; needle in, needle out. Tie off the end. Snip the thread… and start again.

As a result, I have an on-going body of work that is not connected to the landscape. Called ‘In the Fullness of Time’, it is simply about stitch and time. My preference is to use old cloth – either hemp or linen – as it’s full of time in itself. I’m not an embroiderer, I’m a stitcher.

What currently inspires you?

Remote landscape and the visual translation of what I experience, think or feel in that landscape. My aim is one of representational abstraction. Hand stitch is my other inspiration in the sense that the resulting works communicate the meditation of the act. Stitch generates a visual ‘mark’ of time. It is literal texture and can be felt.

Practise for your practice

Tell us about a piece of your work that holds particularly fond memories and why?

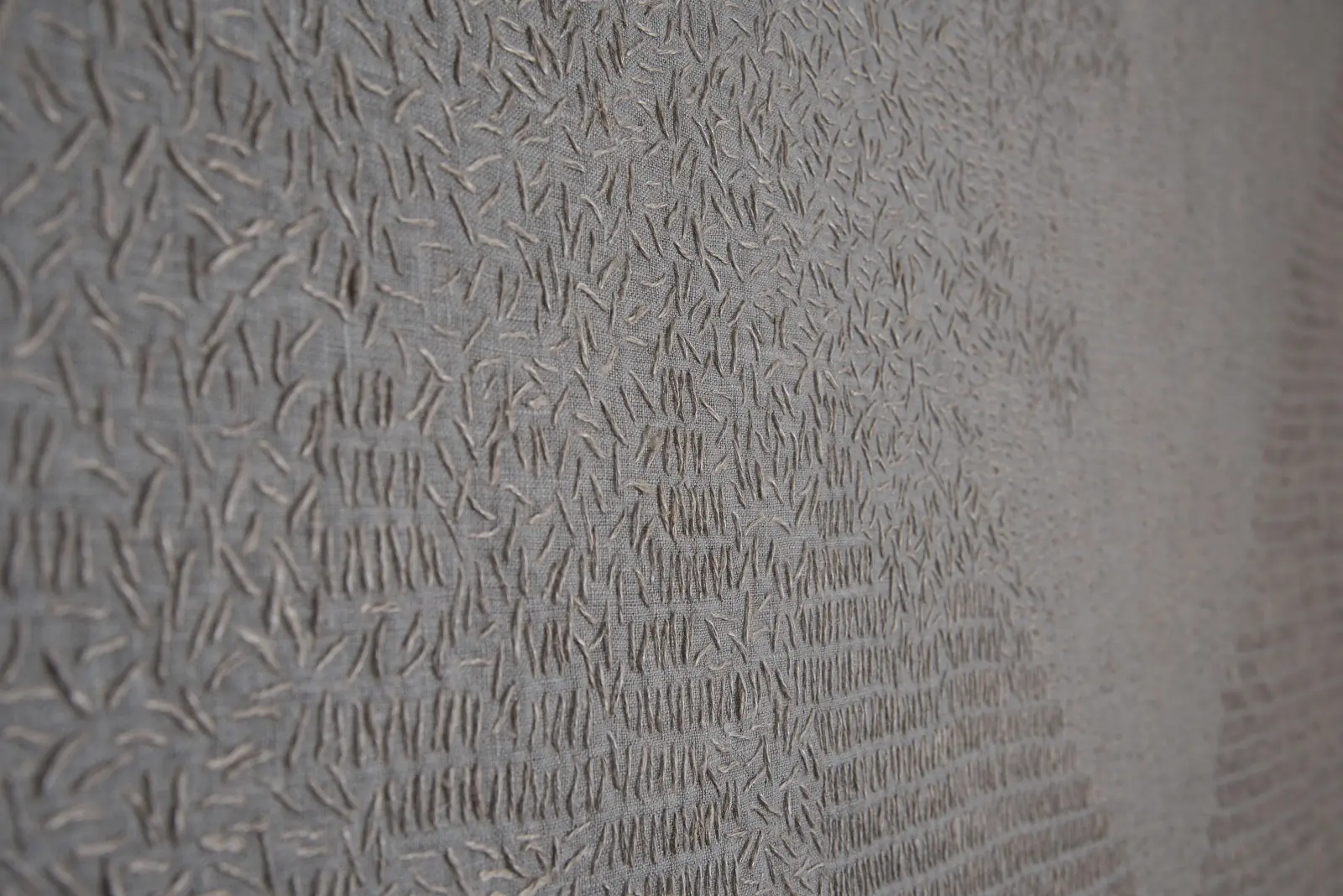

Two pieces of work hold fond memories for me; the first being ’28 Days’, being the piece I stitched in India. Two layers of grey linen, smothered with stitches worked in neutral hemp thread. It took me about 28 days to complete and was part of a healing process.

The second piece I hold dear is “Adobe, Lintel & Ladder’, being the first significant piece using raw earth pigments and stitch to convey some of the key elements of the Acoma Pueblo that inspired it.

How has your work developed since you began and how do you see it evolving in the future?

I would describe my earlier work as being complex, layered and detailed and my evolution has involved simplifying. I would describe my current work as quiet, reductive, simple, serene and contemplative. Agnes Martin said, “your path is at your feet”. I think I’ve found mine and don’t presently feel any desire to deviate from it. I don’t really think about where my work might go in the future, preferring to work in the present and see where that takes me.

What advice would you give to an aspiring textile artist?

Quite simply, “do the work”. Becoming and being an artist involves commitment, discipline, courage, curiosity, a willingness to explore, take risks, learn from failure and then let it go. You cannot establish a practice without practise. Dedicate time in your diary that is sacred to studio work – write in ink! Go into the workspace (studio, spare room, shed – whatever), leave the computer and phone behind and immerse yourself. If you have work or other commitments (such as children, grandchildren, ageing parents), be sure to set boundaries and stick to them. When asked “what are you doing next Tuesday” the response should firstly be “I’m not sure, why?”. You can then look at your diary and seeing “STUDIO’ writ large across certain days of the week can respond with “I can’t make that, I have a previous engagement”. No-one needs to know it’s with yourself.

For more information visit www.clairebenn.com or follow Claire on Instagram and Twitter

If you think your friends would be inspired by Claire’s story, please feel free to share on social media. Just click on the buttons below!

9 comments

rose

my heart sinks usually when paint and textiles collide in an installation, but these works have a clarity of vision in which there is no muddled confusion. your insight is an inspiration to us all.

Brenda Moody

“You cannot establish a practice without practice”. I have written your statement on a sticky note and placed it on my desk in front of me. I have been ducking, diving and deviating from my art practice for too long now. Thank you for the inspiration to help me walk back into my Studio!

Sarah I R Pyke

Really inspiring because I am hand quilting a wall hanging and can say I am somewhat machine phobic. It’s okay to be slow and so beneficial to find contemplation and meditation in it. I’d like to see more of your work. Sarah xx

Janice Bathurst

Thank-you for highlighting the amazing peace that hand stitching gives one. I have just finished my Master of Arts (visual arts) at Edith Cowan University in Perth, Western Australia. All my work was naturally dyed silk using the Eucalyptus Marginata and hand stitching, it was an amazing experience. Thank-you Claire

Donna Thompson

What a fabulous interview…hits all the notes. Claire’s work stirs something deep inside me. It’s just fascinating. I have always preferred hand stitching to machine work. I hand pieced quilt tops in a time when modern quilting techniques were booming and streamlined, machine piecing was so exciting for many because they could work faster and complete more quilts.. People thought I was crazy, but it was the only part of the process I truly enjoyed, slowly stitching every single piece and then hand quilting the layers. Our work should only ever reflect what we truly love…not only the end result, but the process by which we create. Thank you for such inspiring articles.

Arlette Schulman

I also absolutely loved this ! I have done a lot of hand stitching on my own handmade paper. I was born in Egypt, and the Sahara desert was a magical place throughout my childhood. Have been living in Canada for many years……..what a contrast !

Marjet

I love you work, so interestingly derived from nature, very inspiring,

Marjet

I see I wrote a comment in 2019 after this article and agai feel the need to to say I still like your work and attitude.very inspiring.

Monica Scott

I absolutely love this! I have been doing the same thing with getting more into doing handstitching and slowing down. It may seem to others that it takes too much time, but there is something so amazing in freeing yourself from a mindset of getting things done quickly. Machine embroidery is fine, but it just doesn’t compare to hand stitched embroidery. I even spin a lot of my own thread.