This article was first published in November 2020. Sadly, in November 2021 Els Van Baarle passed away after a long struggle with cancer. We are honoured to have had the opportunity to interview Els and hope this piece serves as a fitting tribute to a passionate and talented artist.

You’ve likely heard the saying ‘if it isn’t broken, don’t fix it.’ Why tinker with tradition?

Textile artist Els van Baarle has an answer to that question, as well as a gorgeous body of textile art that demonstrates the power of expanding and building upon tradition in new ways. Els spent years learning traditional batik methods, and then she moved those techniques forward in new and different ways that are remarkably engaging.

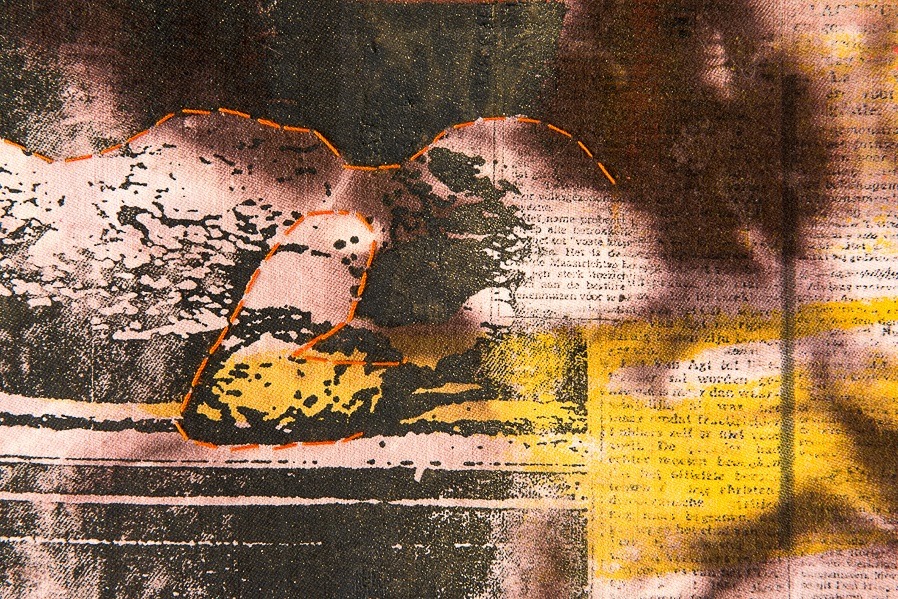

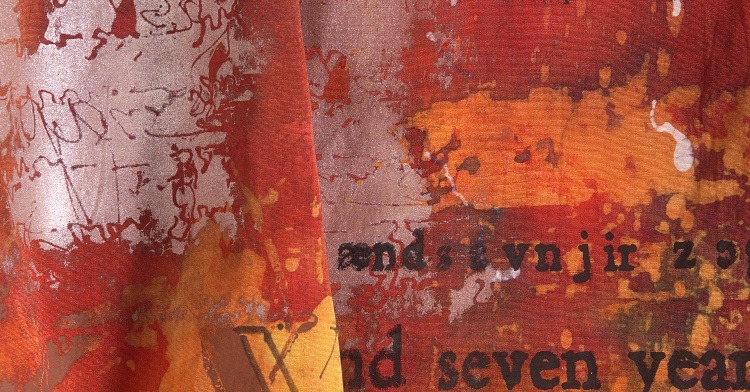

Els’s work comes to life slowly and carefully using traditional batik tools, wax, and paint. It takes time and careful planning to create layer upon layer of colour, paint and mark making.

She then embellishes her pieces with simple, but meaningful, hand stitching.

Els also plays with text in her work, and you’ll enjoy hearing about her recent inclusion of a magical language she created herself.

Els has kindly taken time to introduce us to both her philosophy and techniques. You’ll learn about the traditional batik tools and techniques she uses, as well as the story behind one of her most remarkable works involving 900 correspondence envelopes. Her generous sharing and sense of humour make for an engaging interview.

After reading, we also encourage you to watch this video from her website showing her process in action.

Els is trained as a textile teacher in Delft and worked for many years in education. She now offers courses in adult education and vocational training for textile teachers. Els has both exhibited and lectured across the globe, and her work can be found in both private and public collections.

‘Flower Power’ and other influences

TextileArtist.org: What initially attracted you to textiles as a medium? How was your imagination captured?

Els van Baarle: I love the flexibility of textiles, and also the endless possibilities to use it, reshape it, colour it, and play with it. You have to touch it to appreciate the material. Fabric can be soft, hard, thick and transparent. All of these characteristics will influence your work.

What or who were your early influences and how has your life/upbringing influenced your work?

My early influences came from my mother. She was a seamstress. I was born just before the war, and I remember the shortage of textiles in those years, and also the years after the war.

The first thing I remember doing was taking out the basting thread very carefully from the clothes my mother sewed. And then I had to rewind the thread onto a wooden spool. These threads were used over and over again until they completely broke.

We had nothing. My mother sewed a dress for me and my sister from the kitchen curtains.

Even now, decades later, I think of my mother when I cut and throw away basting threads that could be reused.

This all influenced my love for fabrics. I have rolls and rolls. And I like to touch fabric. I can understand the fact that exhibition visitors try to touch the work (although there is a sign: please do not touch).

What was your route to becoming an artist?

My education was as an art teacher. I learned every possible textile technique, along with drawing, photography and developing photos.

But the moment I started to do batik, I knew immediately ‘this is IT!’ I chose batik as my theses, and my final piece was a large installation from silk organza now hanging in the hall. This was in the 70s when batik was very popular, especially with the ‘Flower Power’ movement.

I very quickly saw the possibilities within this ancient technique. The smell of the wax and transforming white fabric into a coloured piece was what I liked.

I use the traditional tools, including tjanting and the ‘tjap’ which is a copper stamp. But I use the tools and techniques in ways that create non-traditional cloths. My work is about both tradition and innovation.

I also studied the possibilities with different dyes: Procion MX, acid dye, vat dye, direct dye, disperse dye, naphtol dye (which is now forbidden), and indigo.

I had three years of learning the traditional way of doing batik with an Indonesian teacher named Raden Suwondo Sudewo. Then for 20 years, I taught in different kinds of schools and provided further training for teachers.

Ancient tools…modern themes

Tell us about your process from conception to creation

The way in which I work is described in the book I wrote with Cherilyn Martin called [easyazon_link identifier=”1849944369″ locale=”UK” tag=”wwwtextileart-21″]Interpreting Themes in Textile Art (Batsford Press).

I like working on themes, but I always work on different projects. Sometimes a piece has to ‘rest,’ and then I work on something else, often another theme.

The start is very often a walk in the morning with my dogs. Later, when I am home, I write my thoughts in a sketchbook, often using ‘mind mapping’ techniques. I also look for books or use the Internet to read as much as possible about my theme.

I then make samples with the dyes on scraps of the fabric I want to use, as fabrics take up dyes differently. I use Procion MX dye, so the fabric must be natural.

I usually start with a layer of colour—not too dark—because many layers of wax and dye will follow.

When the fabric is dry, I use wax with brushes, tjanting and/or tjap. Then I dye again. This is repeated many times.

A tjanting is a small instrument with a wooden or bamboo handle and a copper head with a spout in different sizes. You dip the tjanting in hot wax, and you can make lines and detailed patterns.

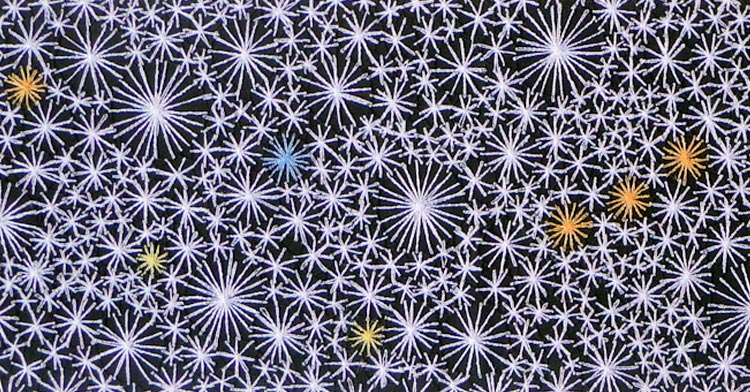

A tjap is a copper stamp with an intricate, traditional pattern. The stamp is also dipped in the wax, then, after some prints on a newspaper to get rid of the excess wax, you print on the fabric. Depending on the amount of copper of the motif, you can usually make four to six prints without putting the stamp in the wax again

I love the slow process of this way of working. It gives me time to think about the next step.

And the work has a life of its own. When the wax is removed, I can add screen printing or stitches. The end result is cloth with a wealth of colours and depth.

Tell us a bit about your chosen techniques and how you use them

Wax and dye is what I mostly do, but I am adding screen print and/or stitch when I think it is necessary. I like handstitching, as it is easy to improve my errors. I am not good in machine embroidery. I also dye my own threads.

Sometimes I combine paper into my work using Procion MX dye.

Fabric is first soaked in soda, and when it is still moist, I start brushing on the dye. The first layer of colour is important. For example, you cannot start with a yellow dye if you want to end up with a blue cloth.

When I was teaching adults, I often noticed many people want instant results. They do not want to spend much time learning colour theory and mixing. And they often want to stop too soon. When fabrics look nice, they are afraid to take it one step further.

But only by taking it one step further will they discover that the work can be better…or that it is a disaster. ‘Trial and error’ is the only way to learn. And discharging is a possibility.

Fabric is such humble material—we are not working with gold! So, why not take a risk with colours and design?

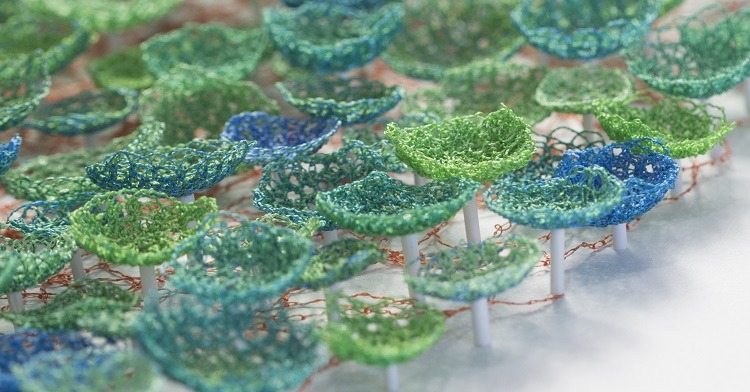

My smaller pieces are often used in book forms. Sometimes, I use a leporello style, for which a long and narrow piece of fabric is folded like an accordion. Both sides of the fabric must be interesting, because an accordion-fold book can be opened and viewed on both sides.

I also use a Japanese rolled book form for which a piece of wooden stick is placed on the left or right side of the piece and then rolled.

Then I add stitching to both styles of books.

What currently inspires you?

I am interested in graffiti and all kids of text. I made a series of works entitled ‘Asemic Writing’ which featured text that nobody could read.

I found the term ‘Asemic Writing’ on the Internet. Several artists use Asemic writing with pen and ink on paper, or markers etc. But you can also make these marks with needle and thread. The work has a mysterious look that I like.

900 envelopes and counting

Tell us about a piece of your work that holds particularly fond memories and why?

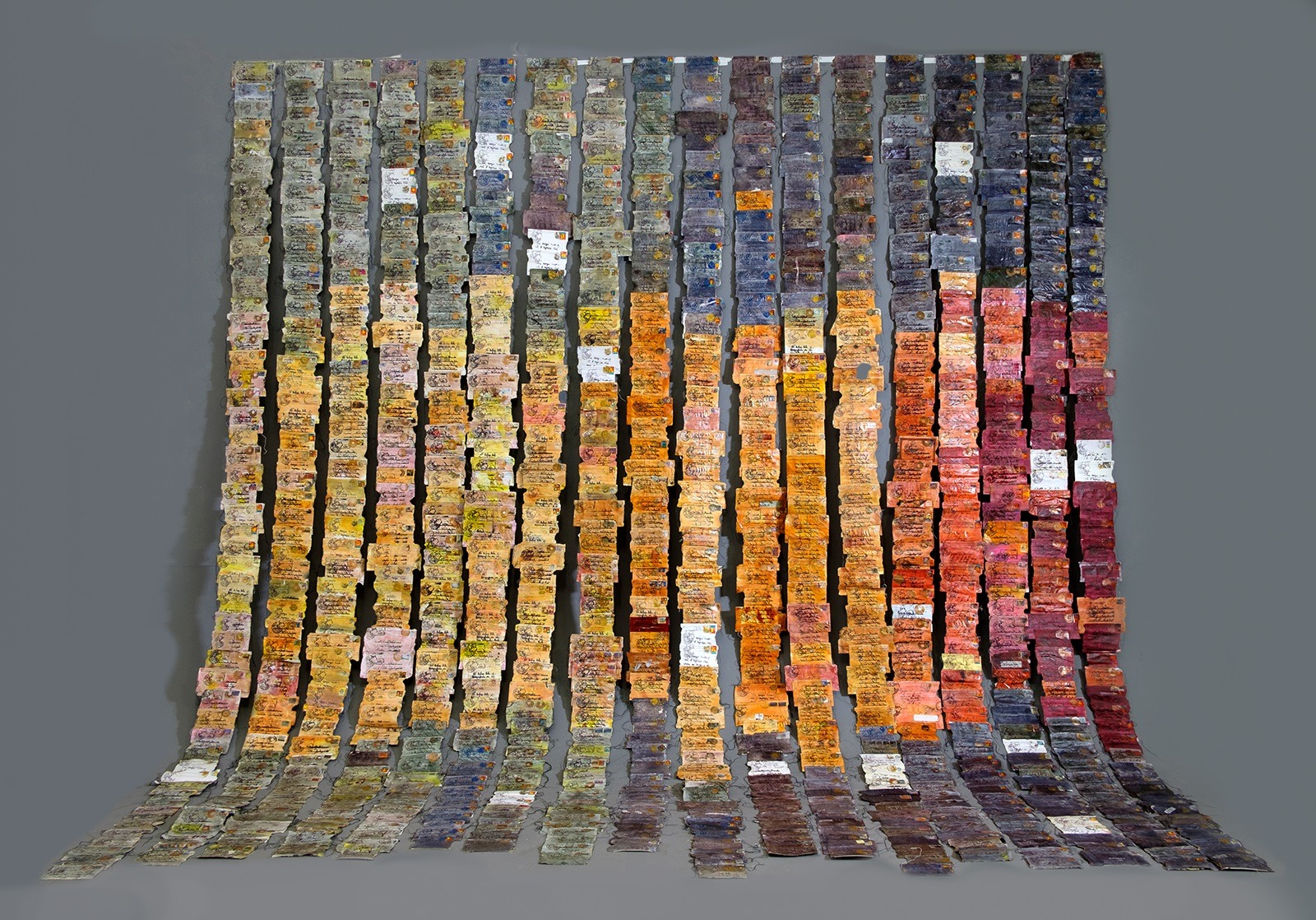

A very good friend died in 2007. He was a teacher at a village school, and he used to collect stamps, as well as stamped envelopes. His collection got bigger and bigger because many of his friends and his pupils’ parents saved their envelopes for him. Everything was neatly stored in boxes.

After he died, his collection of thousands of envelopes was destined to end up in the paper recycling bin. I thought that would be a terrible shame, so I took the boxes home and soon saw potential in how to use his collection in my work.

I started with a series of waxed, dyed and screen printed envelopes in a 2007 exhibition at Fort Rammekens, Ritthem, in the Netherlands. It was an old fort built in 1547.

The newest work in the series, Letters from a Friend IX (2017), is now travelling with the Studio Art Quilt Association (SAQA) through the United States, Japan and Europe. I used 900 envelopes that I waxed, dyed, screen printed and then stitched in rows. The size of the work is 4 meters by 4,5 meters.

I made about nine pieces, and I still have a few hundred envelopes. I thought my large piece would be the last one, and then I would throw the rest of the envelopes away. But, I just can’t!! I have made sketches for new work.

How has your work developed since you began and how do you see it evolving in the future?

I started mostly working on silk, but that has changed over the years. I work on every kind of natural fabric, and I have also used more paper in later years.

My advice would be to keep experimenting, study colour theory, and do not give up too soon.

I love this quote from Rudyard Kipling: ‘Gardens are not made by singing “oh, how beautiful” and sitting in the shade.’

Keep working!!!

For more information visit elsvanbaarle.com

Els has a real passion for batik. Let us know below how you have used batik in your own work.

12 comments

Mimiblue

C’est merveilleux d’être inspiratrice au-delà du temps, au-delà de la vie ; comme elle aimait son travail et comme on aime le travail qu’elle nous a laissé !

Kate Dean

I took a batik class with her some years ago, and have a pile of beautiful cloth waiting for additional techniques. Els passed away on November 11, 2021, and there’s a lovely video of her working, with her house, gardens, and studio along with many of her pieces. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F6E_aUMNkZE It’s on the Textiel Tube channel.

Lia overman

Hi Els, when are you coming back to perth again?

We had such a great time together!!

My home is open for you to come and stay here again!!!

I’ll organise a workshop if you like

Or come and relax, just for a change

Veel liefs

Lia Overman

Perth W Australia

Sue Padfield

Thankyou for sharing your amazing work and inspiration

Helen Marino

Thank You Els for the inspiration to keep creating, experimenting and have fun. Just what I need

these days.

Anja van Dijk

Love you and your work, big hug!

Mary Lee Murphy

Enjoyed the interview.

Anneke Herrold

Els, I loved reading this article. You make such wonderful work! Keep on working!

Kathy

What a great interview at a time when I need inspiration. Especially loved the Kipling quote; it speaks so true to batik. Thank you.

Muffy Clark Gill

I also do work in batik, primarily painting on silk using the Japanese rozome method. There is an international organization from the UK known as the Batik Guild of which I am a member. Please follow us on FB and Instagram. You can follow me on FB@muffyclarkgillfineart and on IG: @muffyclarkgill

Flox den Hartog Jager

Els, wat is je werk toch prachtig!

Margot

Beautiful work and share, thank you