Perhaps the most powerful aspect of figurative art is its inherent ability to tell a story. As soon as an artist stitches a twinkle in an eye, a crooked grin, or hands on hips, a narrative comes to life. As humans, it’s hard to resist paying attention. We’re hard-wired to seek meaning when presented with an artist’s tale: who is this person? what’s going on? what will happen next?

Storytelling with textiles can be especially engaging. Their tactile nature adds a meaningful backdrop, and the patterns and textures created with needle and thread readily embellish an artist’s storyline. Often the materials themselves have their own stories, which also help elevate the impact of figurative work.

Sue Stone is a leading figurative textile artist, and we have published several articles showcasing her creative process and techniques.

We’re now excited to introduce an additional five figurative artists whose work is as diverse as the artists themselves. They all present their unique worldviews with innovative, and sometimes surprising, materials and techniques.

Richard Saja kicks us off with his purposeful historical inaccuracies, followed by Mathilde Renes, whose seemingly simple stitchwork tells big stories of friendship and loss. Ruth Miller next immerses us in her southern American experience, and then Anat Artman meddles with famous historical paintings. Lastly, Melissa Emerson takes us into her world as a fierce Mama Bear.

Enjoy this stitched journey into the human experience.

Richard Saja

Subversive stitching

Richard Saja likes nothing better than adding humour and touches of sass to his textile art. His stitched punchlines come to life by embroidering over historically stoic pastoral scenes to suggest mysterious and often raucous storylines. Traditional French Toile de Jouy serves as Richard’s canvas for creating his subversive stitched tales.

‘Selecting specific areas of a traditional toile print to embroider over automatically subverts its intended use by breaking the anonymity of the pattern. Suddenly, with stitches and colour, motifs are brought to the fore, demanding attention. Added imagery becomes provocative in social, political or cultural ways.’

Richard had first embroidered this print using the colour spectrum blocked out across the two figures. But for this piece, he wanted to make the embroidery more intricate and ornate. He also sought to have the colours interact in a wholly new way.

‘I wanted to draw out the conflict evident in the body language of the two figures. The man is clearly entreating/declaring, but the woman turns away, proffering a token crown instead. The title describes its depiction: LOVE is compromise. And the sumptuousness of their clothing holds no advantage over the complexity of emotion.’

Over 20 years ago, Richard had a small decorative pillow company where he taught himself how to embroider out of necessity to fulfil orders. He found he had a certain talent for needlework at the time, and through practice and experimentation, he has developed an artistic voice uniquely his own.

Monsters, aliens and human-animal hybrids often feature in his work and hark back to Richard’s childhood. Having felt like an outsider while growing up, Richard identified with monster movie characters who were targeted as ‘bad guys.’ Over time, those stitched characters grew to become an iconic feature in his altered scenes.

Richard doesn’t have any favourite stitches. He’s instead interested in exploring the ways stitches work together with colour to create textural surfaces. He also embroiders over Aubusson tapestries, which exposed the close bonds between embroidery and knot making that he chooses to exploit.

‘I don’t claim to be a traditional needle worker. I find the establishment to be very regimented and inflexible, and in my mind, there’s no room for that way of thinking in the creative arts. It’s prose versus poetry. My work isn’t interesting to me if it’s not amping it up a couple of notches.’

Richard Saja is based in the Village of Catskill in the beautiful Hudson Valley (NY, US). His work is included in many private collections, as well as the permanent collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. He has exhibited globally, from the Museum of Fine Arts (Boston) to the Chung Young Yang Embroidery Museum in Seoul, Korea.

Website: historically-inaccurate.blogspot.com/

Instagram: @richardsaja

Mathilde Renes

Dearest friends

Mathilde Renes has added to her illustrated diary every day since 1997. Her whimsical pen and watercolour sketches document her varied, and often humorous, life events. They also captured adventures with her best friend, Wilma, who sadly passed away from cancer in 2020. Mathilde is now creating a stitched series from those drawings called Sweet Memories.

‘We were friends for more than 50 years. Soulmates. Remembering our friendship through embroidery is a way to process my grief. We visited often, and we’d bring flowers to each other because we loved our gardens. You can see the bouquets and a book about gardening on the table. We also loved to read, so there are many books in this work.’

Mathilde doesn’t trace her diary sketches onto fabric before stitching. She instead picks up a needle threaded with black DMC floss and starts ‘drawing’ with her needle, only using the sketch as a reference. Once a scene is outlined, she then fills in the details with more DMC threads using ordinary flat stitches. Sometimes lazy daisy stitches are used for dress patterns or other textures.

‘I take the same liberties when stitching my figures as I do when drawing in my diary. They are not very realistic. They’re more an interpretation, but I do try to capture a person’s key characteristics.’

Indeed, Mathilde’s attention to characteristics and details of her figures are a hallmark of her work. It’s remarkable how seemingly simple stitchwork can tell a big story. And speaking of key characteristics, Mathilde gives herself a ‘signature’ hairstyle in both drawing and stitch: a bright yellow hair bun held with a large hairpin.

‘I’ve tied my hair in a knot since forever, so I always picture myself with the same haircut and very often from the back. At first, I used different coloured hairpins, but I later decided red would be my trademark, so to speak. Nowadays, I’ll often start a diary drawing or embroidery with my hair.’

Mathilde is largely self-taught, and she started her textile art journey by knitting vases. After inheriting embroidery materials from her aunt in 2013, Mathilde decided to try embroidery. But where to begin? Eventually, she realised her diary held the key, and she’s been stitching her life story ever since.

Mathilde Renes lives on a houseboat (formerly a cargo ship built in 1911) next to a large garden in Spaarndam, Netherlands. Her studio is the garden house, which also serves as a greenhouse (especially in spring) and hiding place. Mathilde has exhibited her work in local solo and group art shows.

Website: mathilderenestextielkunst.exto.org

Facebook: facebook.com/mathilde.renes

Instagram: @mathilde_renes

Ruth Miller

Life-sized storytelling

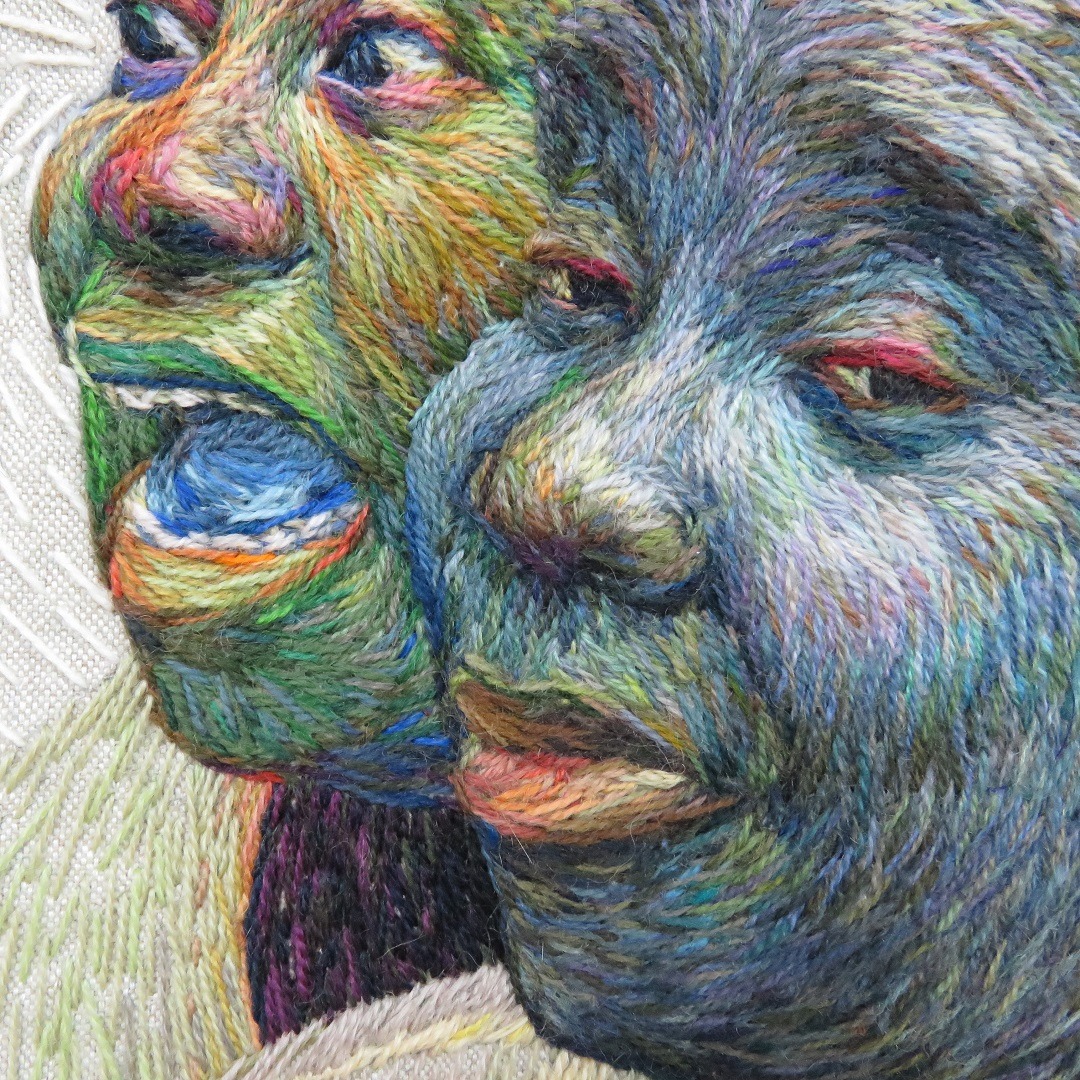

Ruth Miller’s website bears the perfect moniker: Embroidered Realism. Her life-sized tapestries feature exquisite skin tones and dress through countless layers of different coloured yarns stitched with hundreds of simple stitches. When viewed closely, you’d swear her subjects were breathing.

‘There’s a lush much-ness about embroidery that’s very appealing. So many discrete threads lie beside and atop one another in a series of visual strategies that use colour and stitch direction to form pieces of a puzzle. The textural quality of embroidery adds a third dimension.’

Congregants in the Church of the Like-Minded features three images of a customer at Ruth’s daughter’s beauty shop. Ruth started chatting with the woman to pass the time and she quickly noticed the woman’s very expressive face. “I thought her expressiveness was a form of emotional courage.”

Ruth asked to photograph the customer as they continued to speak, and those images were then combined into this work. “The emotions we feel tend to become habitual and attract others that are similar as if they were congregants in the Church of the Like-Minded. The non-traditional skin and hair colors are meant to emphasize those feelings and also provide a space for me to experiment with how far I can take an image while still allowing it to be easily recognizable as a real person. I also didn’t want her to think I was making fun of her. Many Black women not only feel left out of discussions of beauty; they’re often ridiculed or dismissed as well. So, before even setting pencil to paper to create Congregants…, I stitched a more naturally-hued depiction of the same model called Our Lady of Unassailable Well-Being. My hope was that she wouldn’t feel I, too, was casting aspersions. If you think that’s an extreme accommodation, imagine sitting for a portrait and being handed a Cubist rendition by a not-yet-famous Picasso. It would be shocking.”

Ruth first created line drawings from her photos, experimenting with various coloured renderings using pencils. She then cut them out and explored different placements. Once a final composition was chosen, Ruth stitched the piece with 100 per cent wool tapestry yarns because of their durability, colour fastness and availability in hundreds of shades.

In person, a slight sheen is visible on each strand. And viewers are surprised to discover the sweeping curves and movement were actually created with simple straight stitches. Ruth credits the colour-theory lessons she received from Hannes Beckman at Cooper Union for playing a key role in bringing her figures to life.

Ruth Miller is based in Mississippi, US. She has received several awards for her work, including the 2019 Mississippi Governor’s Award for Excellence in Visual Art. She also teaches across the US, including the Penland School of Crafts. And her tapestries have been exhibited at the Mississippi Museum of art and the Huntsville Museum of Art (Alabama, US).

Pinterest: pinterest.com/catahoulams/

Anat Artman

Reimagined masterpieces

Years back, Anat Artman needed something to hang on the wall in her new flat. So, she created a stitched collage, and she’s been doing so ever since. Anat especially enjoys reinterpreting famous old paintings, swapping original figures and settings for her own imagined storylines. Anat’s first inventive collage was based on pre-Raphaelite painter John Everett Millais’s work Mariana. She had just read the book The Sympathy of Things by Lars Spuybroek about a woman rejected by her fiancé. Anat reimagined the book’s character as being the figure in Millais’s painting who stands by her embroidery, hands on hips, eyes looking up at the ceiling.

‘All of the paintings I use as reference feature a woman and some sort of fibre work. I can easily identify with these women, and the paintings usually contain lots of interesting patterns that speak to me.’

Good at Lounges was inspired by Jean-Edouard Vuillard’s Madame Hessel on the Sofa. Anat used scraps and recycled fabrics from discarded clothing, many of which she found in bags near garbage bins. She started with a rough sketch on a base fabric and then developed the piece bit by bit from there. Most artistic decisions were made as she worked, and everything was stitched by hand using a simple whip stitch.

‘I was drawn to Vuillard’s use of patterns and the way the characters are almost lost in them. For this work, I looked for a character that was sitting on a sofa, which is what I do most of the time.’

Anat enjoys creating titles for her works that feature some kind of pun, and this piece features an interesting word play. While Anat doesn’t normally add text to her work, her inclusion of the word ‘sofa’ in multiple languages serves as both pattern and punchline in a fun way.

‘In Hebrew, the phrase good at languages sounds like good at sofas. But translating the pun was difficult in English. I looked for a synonym for sofa that sounded a bit like language, and the closest I could find was lounge. That started me on a journey of researching the word sofa in other languages, which I then stitched onto the work.’

Anat Artman is based in Jerusalem, Israel, and is a member of the TextileArtist.org Stitch Club. She earned degrees in architecture and philosophy, and she has taught architecture at Bezalel Academy for almost 30 years. She has shown her textile art in group and solo exhibits and featured in the Studio Art Quilt Association (SAQA) Journal and SAQA’s online gallery.

Facebook: facebook.com/anat.dart

Instagram: @anat.dart

Melissa Emerson

Life’s tender moments

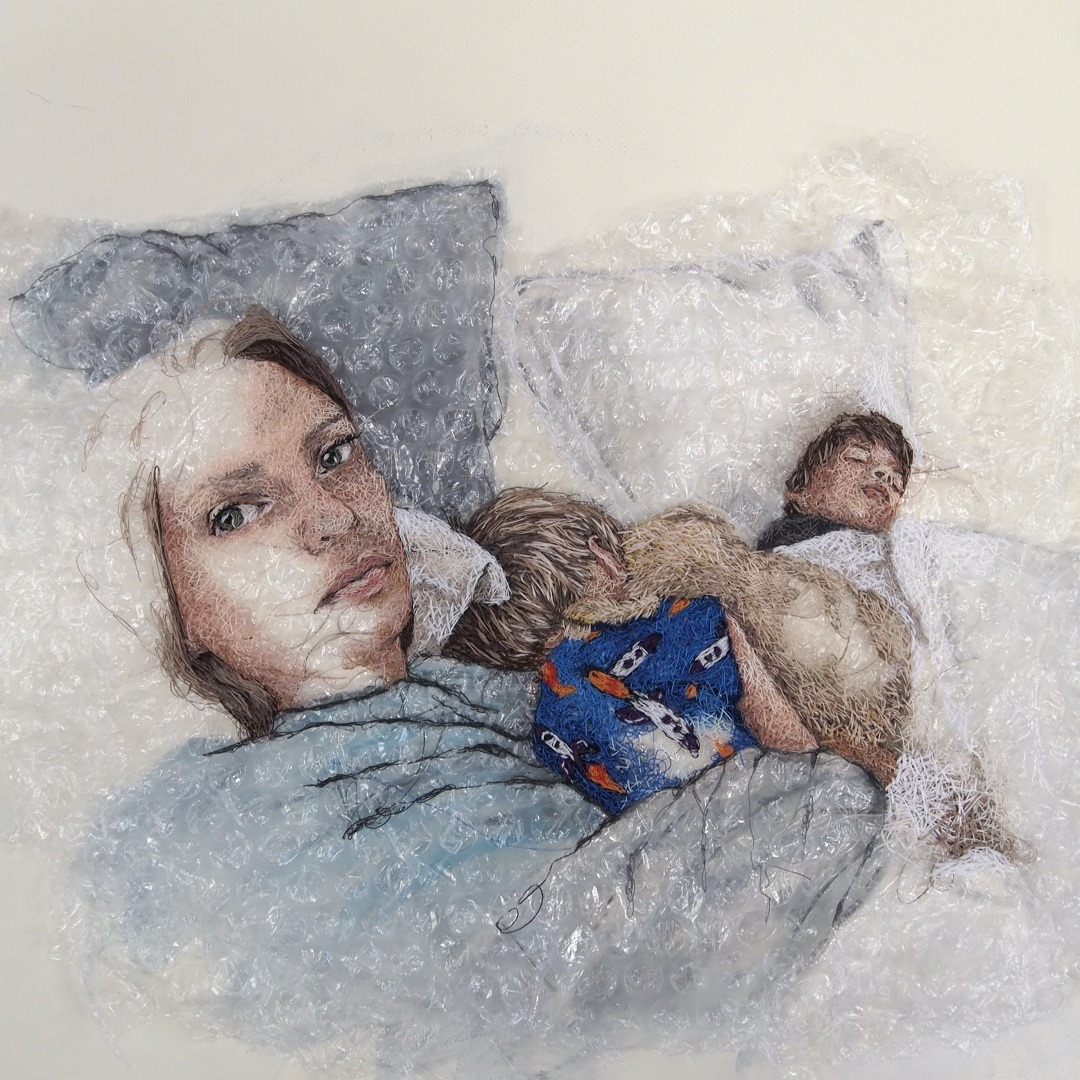

Melissa Emerson isn’t afraid of tricky surfaces on which to stitch. The more fragile or precarious, the better. One of her most delicate works was stitched on a paper napkin featuring Melissa and her youngest son, legs entwined. When her son accidentally tore the work, she simply repaired it, recognising that mending and carrying on is what life is about. She also thinks the tears only added to the work’s meaning.

‘Memories create who we are, and they shape our future. I am acutely aware that time is precious and fleeting. Sewing helps me capture those memories, cementing the times and places of tending interactions. My muted colour pallet and incomplete details also reflect how memories fade over time despite my strong desire to try and hold on to them.’

Mother, Protector is hand stitched on bubble wrap using sewing machine threads. Several thread layers were first randomly built up to create tones and textures, and then Melissa later reworked areas to achieve more complex details. Some areas of the piece were purposely left incomplete to help direct viewers’ attention toward Melissa’s gaze and her children’s expressions, poses, bedding, and even a stuffed toy dog. And the muted colour palette reflects how memories fade over time.

‘Each piece starts with a photograph, and before I start stitching, I spend quite a lot of time thinking about what I want the piece to say. Many factors influence the direction of my work, so I tend to include or exclude certain elements based on what I want to be the artwork’s focus.’

Melissa often draws her figures on water soluble fabric and then overlays that onto her base foundation. Once stitching is complete, the soluble fabric is washed away. She describes that ‘reveal’ as both nerve wracking and exciting. Melissa also avoids overplanning pieces when creating, as she often changes her mind as a work evolves.

‘I find stitching on delicate surfaces provides an ephemeral base that enhances the feelings of fragility and strength we felt as a family during lockdowns and moving from the UK to Australia. And I chose bubble wrap for this piece as it’s designed to protect things that are fragile, to stop them from breaking. I very much see this as part of my role as mother.’

Melissa Emerson is originally from the UK and now temporarily resides in Canberra, Australia. She previously worked in art education and has been developing her own art practice since 2017. Her work has been exhibited in the UK and Australia, including England’s touring Covid Chronicle textile exhibition (2022).

Website: melissaemersonart.com

Instagram: @mel_emart

Comments