Gavin Fry is a hand embroiderer and collagist. He recognises that both the world and how he feels about it change constantly, and so Gavin develops his ideas and documents these in his visual diaries and artworks.

Gavin originally studied embroidery at Goldsmiths College in London under renowned and inspirational teachers, Eirian Short, Constance Howard and Audrey Walker. He is now a lecturer in visual communication at the University of Brighton where he gained his doctorate. Both his teaching and research are key to his art practice.

Gavin’s work has been showcased in exhibitions across the UK throughout his career from 1986 until 2019, his most recent being a body of work for the 62 Group exhibition ‘Construct’ at Sunny Bank Mills Gallery in Pudsey, West Yorkshire.

In this interview, Gavin describes his most recent work, ’24 hours in Police Custody’ which he developed for the exhibition and which was inspired by the Channel 4 drama of the same name. Gavin takes us through the story of his visual diaries – with Debbie Harry making a guest appearance – and shares with us how he combined his beloved techniques of collage and hand-stitch with carefully selected printed cloth and thread to craft this intriguing piece.

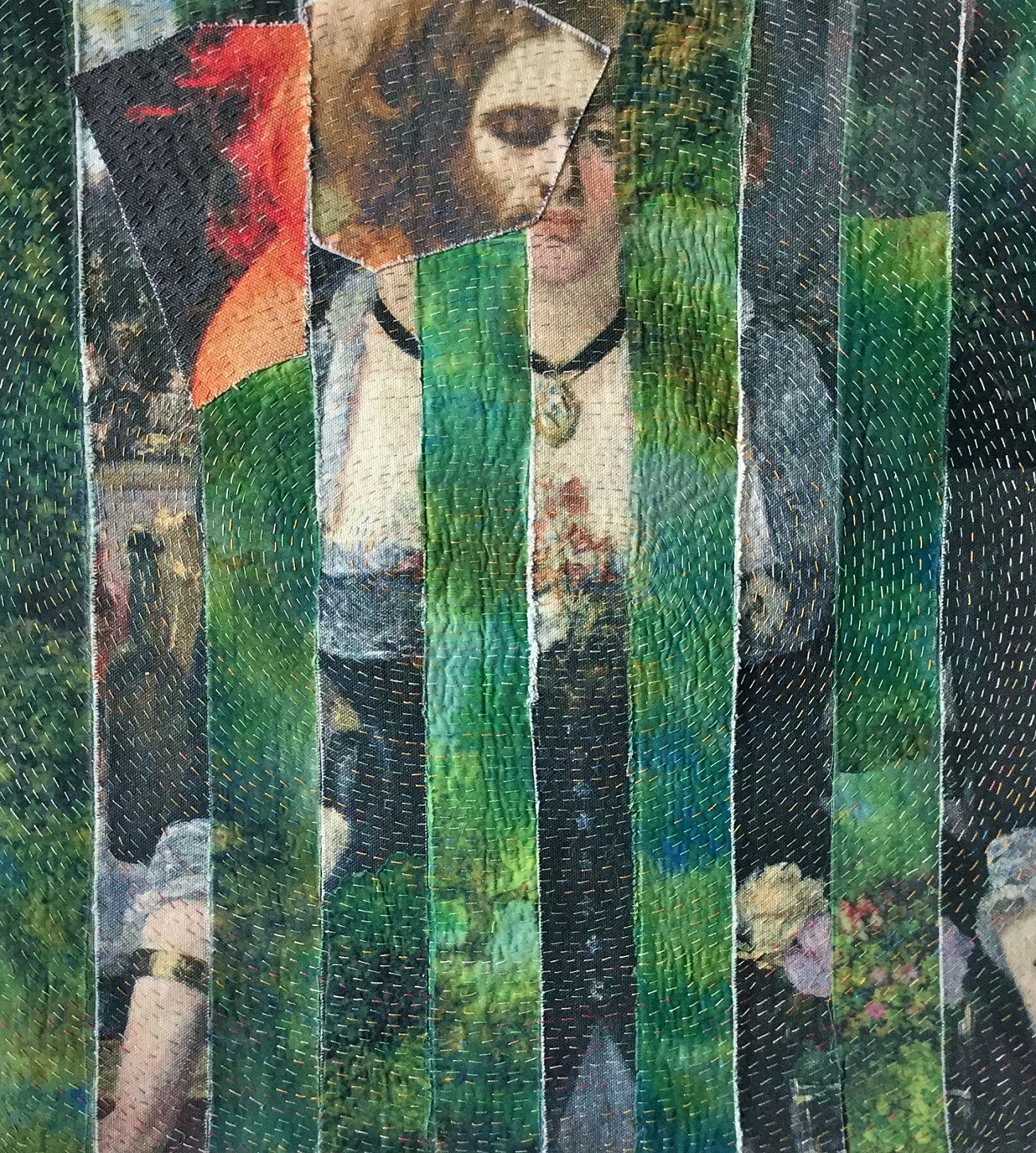

Name of piece: 24 Hours in Police Custody

Year of piece: 2019

Techniques and materials used: Collage and hand stitch, Printed cloth and thread

Size of piece: 38 x 41cm

Collaging new from old

TextileArtist.org: How did the idea for the piece come about? What was your inspiration?

Gavin Fry: The idea belongs to a body of work that examines how second-hand imagery functions and how we value originals and replicas. Because, nowadays, it is a common occurrence for a copy to be seen as equal to an original – in terms of favour and any false assumptions regarding perfection – I wanted to examine this notion. So, I set out to construct work that asks us to appreciate impaired or defective images.

These are those that I have bastardised but which have gained some additional qualities through the process. These additions might be material and/or associative. Hence, the use in this work of second-hand, or already existing, imagery and why I chose to use collage as the main technique. I wanted to put together new from old images, or their parts systematically, to build and assemble new ideas using degraded – and not original – materials.

What research did you do before you started to make?

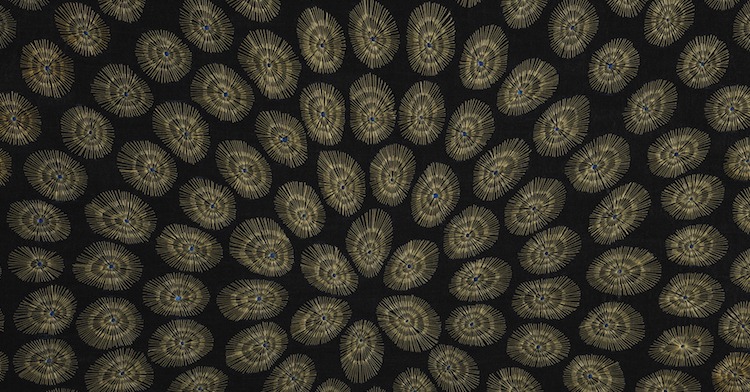

I looked at a lot of collage work made by others, in particular the work of Lucas Samaras, the Macedonian American artist (born 1936) who made extraordinary textile works in the late 1970s and early 1980s. These he called reconstructions and presented them as paintings; they are stitched patterned cloth. The choice of pre-existing cloths registers closely with how applique and patchwork function and Samaras’ images are apparently non-representational but highly biographical.

The other strong influence is Jiří Kolář (1914–2002) the Bohemian poet who made collages and sculptures to explore iconic images from art history, building them into chopped-up amalgams of stripes or screwed-up compositions.

Other research took the form of gallery visits, and the recent show at The National Portrait Gallery in London showcasing the film and collage work of John Stezaker (born 1949) proved very useful.

Combinations that argue or jar

Was there any other preparatory work?

The finding and printing of the cloths and images I want to work with always takes time. I tend not to keep great hoards of materials in order to avoid using the same things over again; I prefer to source for each work anew.

I choose images of artworks that I love and am familiar with. I take the same approach that Samaras took with fashion fabrics because his mother was a seamstress: I choose artworks because I grew up fascinated by art history and now teach art/visual communication.

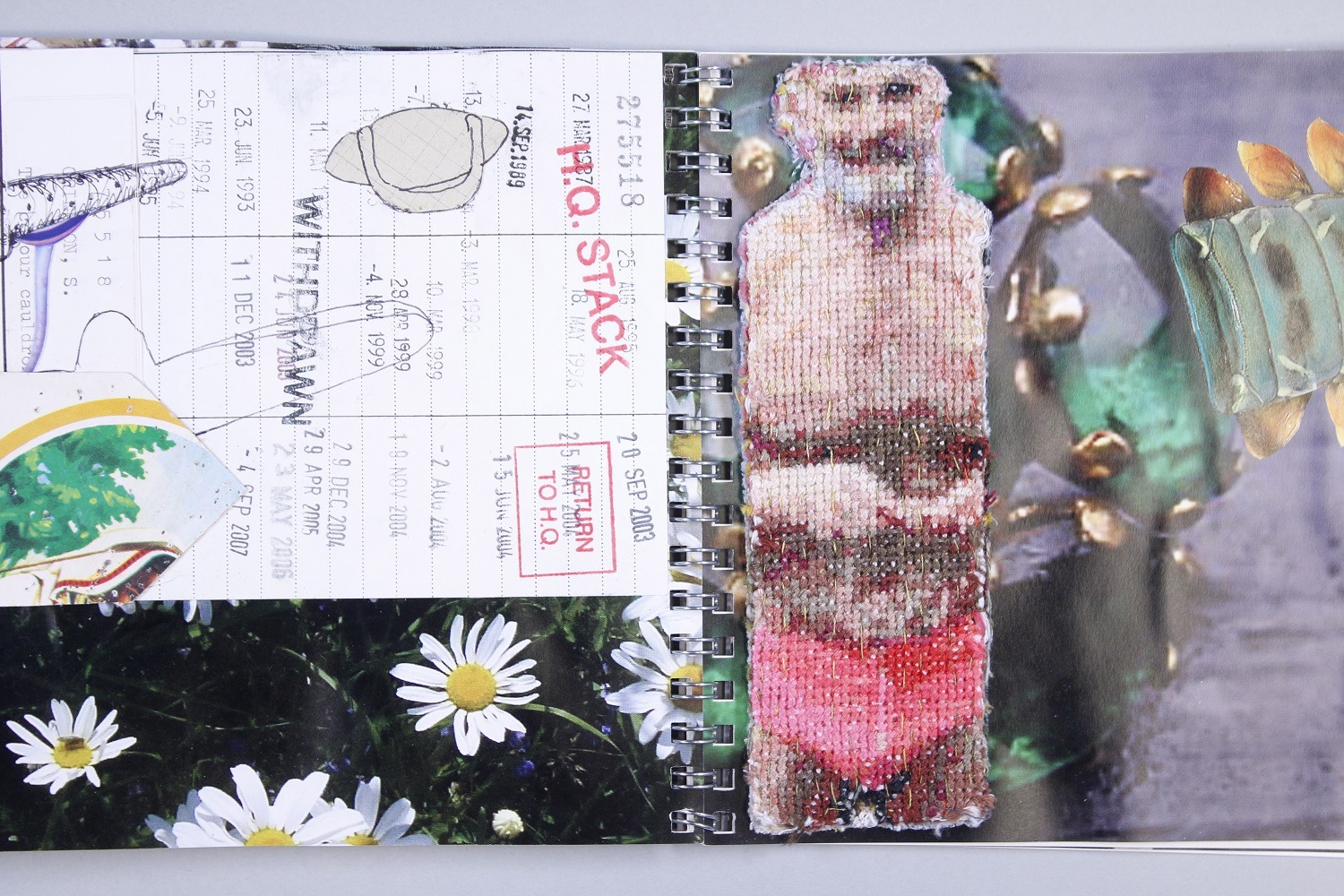

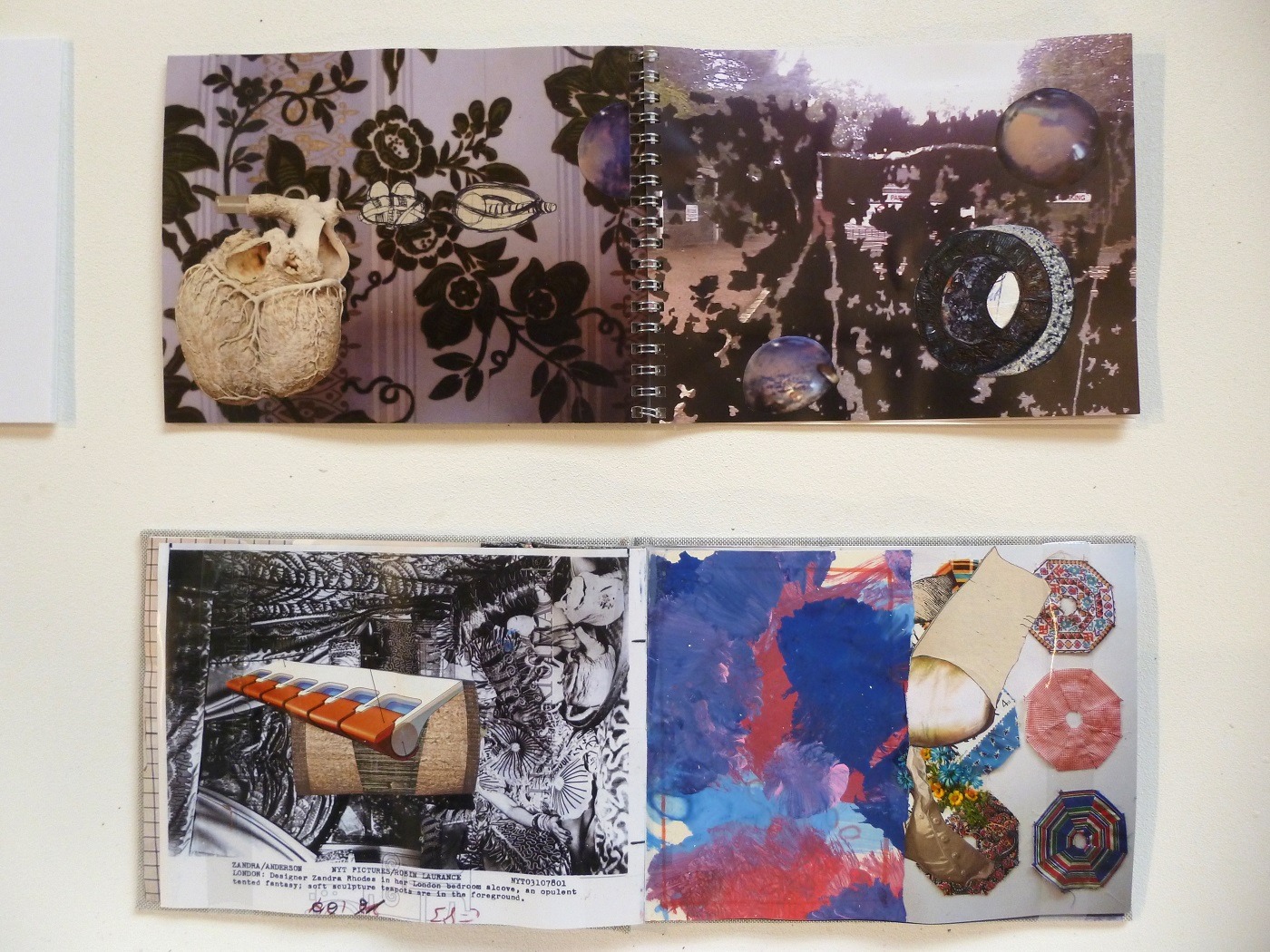

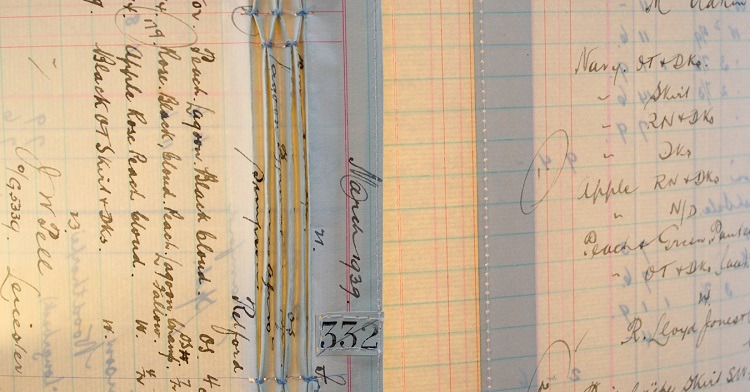

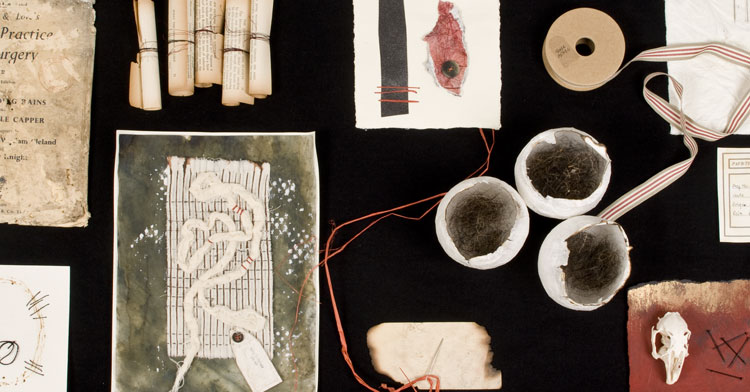

Combinations that argue or jar take time to find and I like to work in visual diaries at an early stage for a new body of work. These consist of anything I want – any medium and working method; they sometimes take the format of a book but could also just be embroidered/printed or collaged images that are loose.

The diaries pictured here all hold information – sometimes visual and at other times technical – that actively documents my practice as I go along. They are often the most satisfying aspect of my art practice because they are made for myself, although parts do get another life as artworks for exhibition in their own right.

What materials were used in the creation of the piece? How did you select them? Where did you source them?

I used printed cloths, machine cottons and found fabrics. These were sourced as tea towels and tote bags from shops or bought second-hand, and others were commercially printed to my design.

For the embroidery, I used machine cotton and this included spaced-dyed quilting thread that is a bit stronger. Being spaced-dyed (and with four or five colour changes on one spool), this poly-cotton thread gives me less control over the colours and I like this. There are also some hand-dyed silks stitched in smaller areas.

What equipment did you use in the creation of the piece and how was it used?

The whole piece was made by bonding fabric strips onto a plain dark background. Then I did a lot of repetitive hand stitching. This is how I directly build onto/into a structure; so the equipment I used was, certainly initially, brain and hands!

The picture of the brain is a photograph I took at a market; the item was a lovely thing but beyond my wages. I take a lot of such images and they go into my visual diaries too. Although they provide original source material, their function is purely diaristic.

I do use an old Bernina machine (circa 1977) but not on this piece. I use this machine because it is a metal casing domestic machine. I call it a warhorse; indestructible, especially when using denim needles. I have had it serviced only three times in its life.

Collage, cutting and Kantha – a cavalier approach!

Take us through the creation of the piece stage by stage

The artwork ’24 hours in Police Custody’ was worked on during the evening and at weekends whilst watching TV and Netflix. This is how the title came about because I was often engrossed in this particular programme of the same name (a harrowing Channel 4 police real-crime series set in Luton where I come from).

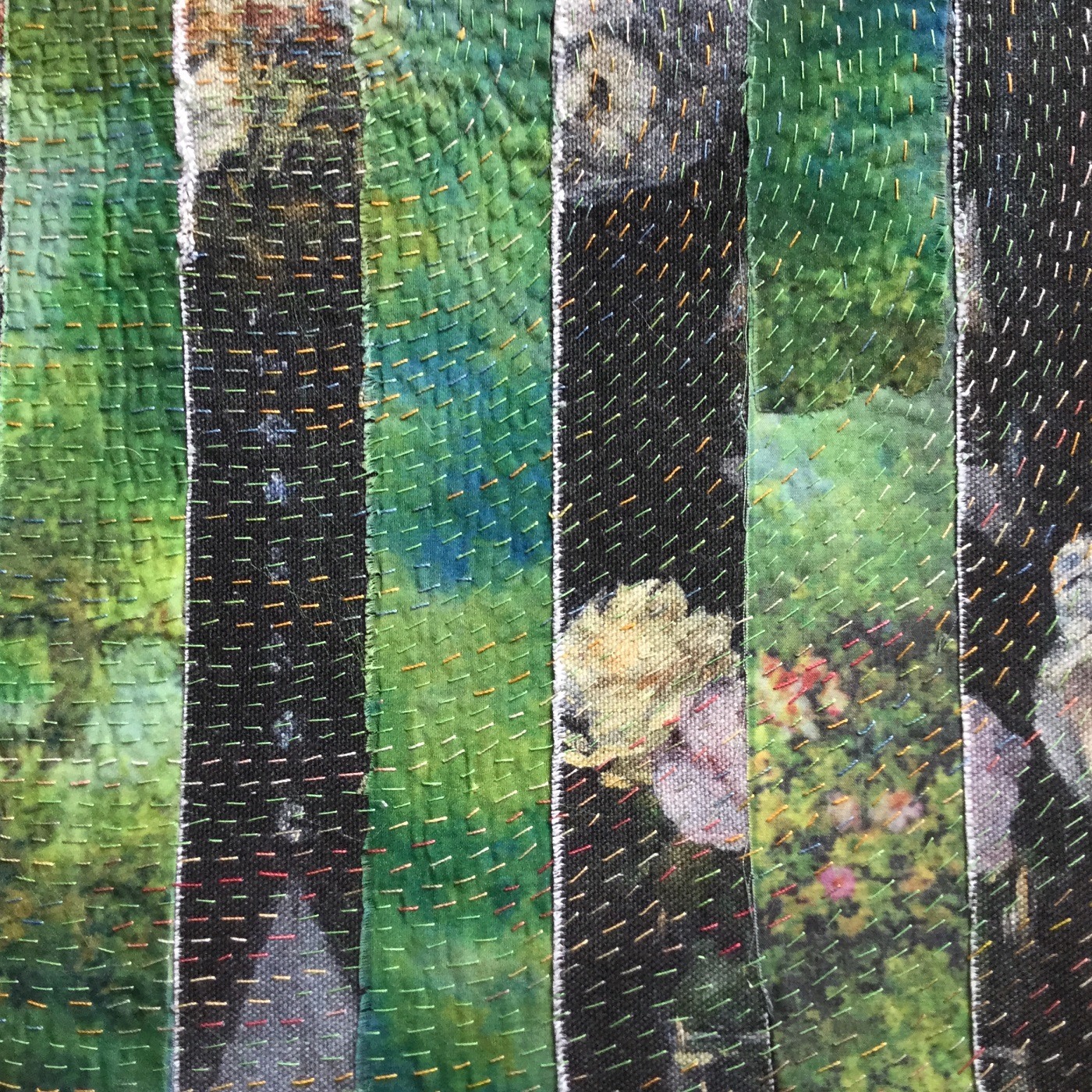

Initially, I made several investigative works, both large and small, using traditional patchwork techniques. I had used these before, but the associations with domestic textiles were too strong, so I began layering strips of cloth in a collage format. These moved around a lot and so, when I had them ideally placed, I bonded them onto a fine tana lawn backing. Then I stitched into it. Sections were added on top and others removed as I went along.

Previously I have always used a sewing machine, but recently I have found all those seams visually (and also physically to sew) intrusive – also, having no seams speeded up the making process. Collages are all about addition and subtraction, and so by not machining, it made this a much more do-able and fluid approach. What’s more, by using the technique of bonding, I could correct elements more quickly and behave in a much more cavalier fashion!

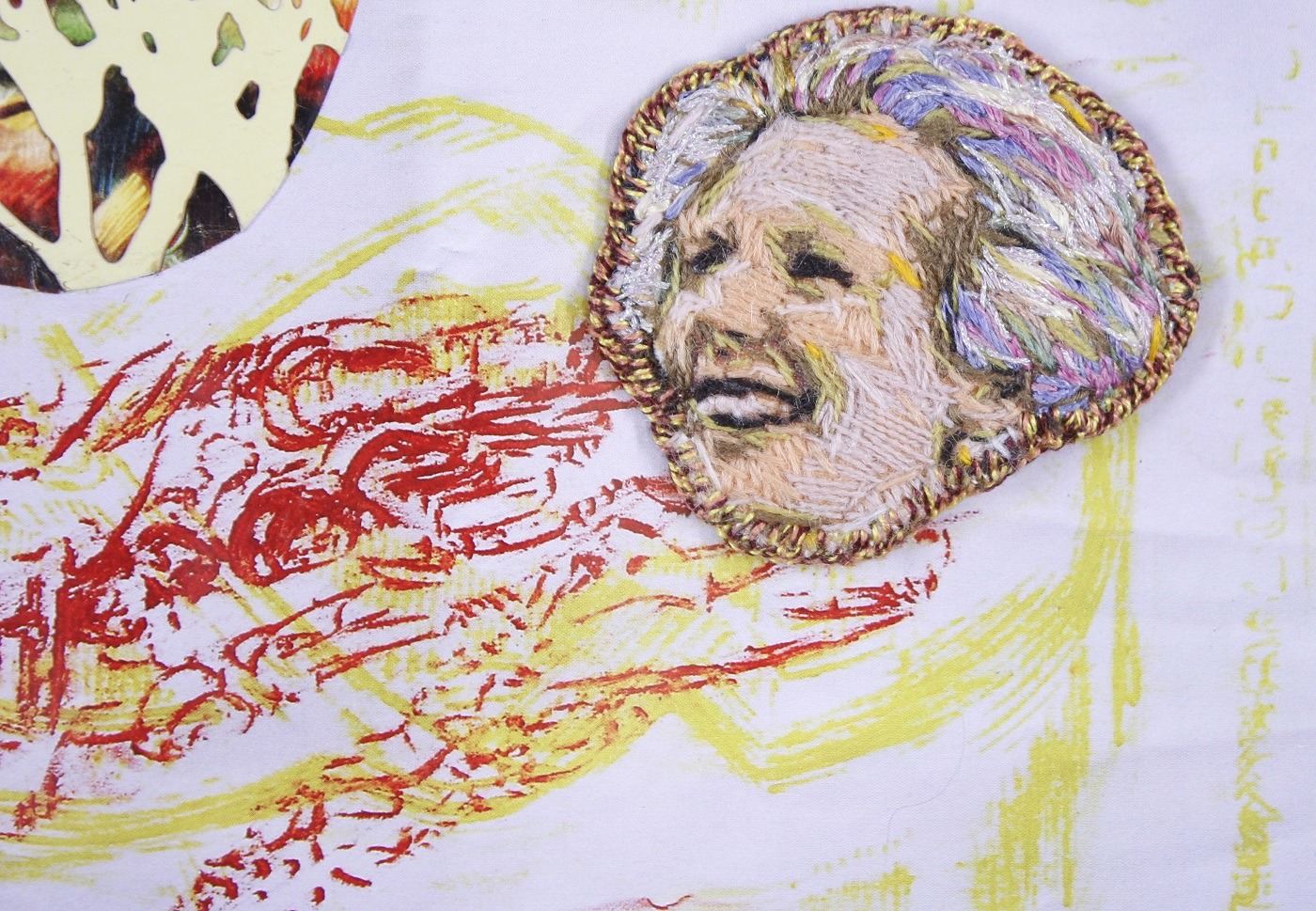

During the development process, the subject content evolved and it is a pickle really: Manet’s barmaid meets Caravaggio’s martyr (with a dash of Debbie Harry). The construction morphed, and I stitched and cut then stitched again (Audrey Walker MBE born 1928 taught me that an embroiderer’s best friend are his scissors).

The ‘Debbie Harry’ image pictured was a smaller quicker work – a preliminary piece made as much to look at subject matter as it was to try out technique. Although no physical elements from it element made it into the final piece, I do a lot of work that assists with the forming of ideas and it’s all valuable.

The embroidery, as is usually the case, is simple to do and easy to apply. It needs to be fluid in approach and integral to the making. So using backstitching and a quilting stitch from Bangladesh called Kantha, the content of the work grew into a Ballad of Reading Gaol portrait of Oscar Wilde – all banged up – and it was only then that the stripes became bars.

Intense art-working is an ebb and flow process, and has a trans-cognitive aspect; I can think about one thing whilst making another – it’s in sharp contrast to the professional teaching that I do during the week.

What journey has the piece been on since its creation?

The piece was selected for the 62 Group exhibition ‘Construct’ at Sunny Bank Mills Gallery that ran from July until September 2019. The gallery is in Pudsey, West Yorkshire, England.

I am a new member of the 62 Group, which is an artist-led organisation that aims to incorporate and challenge the boundaries of textile practice through an ambitious and innovative annual programme of exhibitions.

The work has left the show now and there are no future plans for it. There is only so much room under my bed, and so most probably it will end up being cut up, reworked and edited. There are areas in the final piece that could have another life if I don’t sell it.

For more information visit the 62 Group website.

Has Gavin’s approach given you any new ideas for your own textile art? If so, please tell us in the comments below.

2 comments

Jayne Terry

Thanks Jane,

Very enjoyable read about Gavin Fry and his stitch work! He has given me quite a few things to think about. Now to google Kantha.

Jane Axell

Thank you! Glad you benefited from Gavin’s sharing and Kantha is wonderful – enjoy!