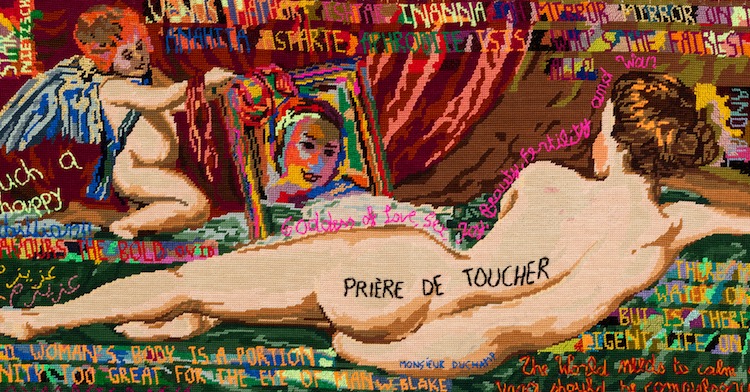

Knitting, crochet, weaving, felting, dyeing, and embroidery are just a sampling of the dozens of fibre-based techniques Jodi Colella works with and teaches. Her textile sculptures and installations create a bridge between artistic expression and activism. Jodi calls her work durational handwork with a fetishist focus; it embodies the complexities of vulnerability and power and embraces the ideals of labour, process and community.

With the aim of effecting societal change through her art, Jodi harnesses a disparate array of found objects and the power of needle and thread. She uses the aesthetic and technical possibilities of materials to bring her ideas into form.

Awards, exhibitions, articles, workshops and projects positively drip from Jodi. She exhibits and teaches internationally including China, Greece and Australia. She is a member of Boston Sculptors Gallery, and is a recipient of a 2019 Massachusetts Cultural Council Fellowship Award for Sculpture. Following a BA in Biology, she studied art and design and is the founder of the fibre study group FiberLab.

In this interview with Jodi, you will discover how 20 years of graphic design for clients led her to find the courage to express her own voice in her own work. You’ll learn about the concepts and messages she portrays with her sculptures and installations, and how diverse experiences such as a scorpion in a mud hut in Thailand became textile art once she got home.

Finding my own voice

TextileArtist.org: What initially attracted you to textiles as a medium? How was your imagination captured?

Jodi Colella: As a child, knitting and other handwork was the shared language between the very complicated women in my life. Knitting in particular provided a portal for us to connect. A space to sit, listen and learn, distracted by the details of stitching but mindful of being present with each other. Those moments of respite and peace in an otherwise chaotic environment is the comfort that I’m chasing each time I set to work. My practice is durational where the process is as important as the content and embraces the ideals of labor and community.

I’m interested in the stories, most often of women, that call upon histories of craft traditions where crafting is social, political and communal. Historically, craft production was a place where expression was encouraged, voices could be heard and where social connections were forged through craft.

What or who were your early influences and how has your life/upbringing influenced your work?

In my family I was the ‘art’ kid. The one who lost herself in drawing and saw things differently than other members who found my wanderings amusing. My other love was science, and lacking courage and support (mostly courage) I chose to major in science instead of art. Graduating with a BA in Biology I first worked as lab technician at a research institution in Boston MA directly across the street from an art school.

After a year of watching the activities of the students out my lab window I enrolled in a certificate program for design hoping that this would satisfy my need to create plus provide employment opportunities. Design was a joy, until it wasn’t. After 20 years of graphic design projects with reputable companies, it was time to work with my own voice instead of communicating the voice of my clients.

My science background informed my earlier sculptures, objects that reflect on the systems of life forms as metaphors for the human condition in its most primitive state. Since then my objects have evolved into larger, broader conceptual structures and installations.

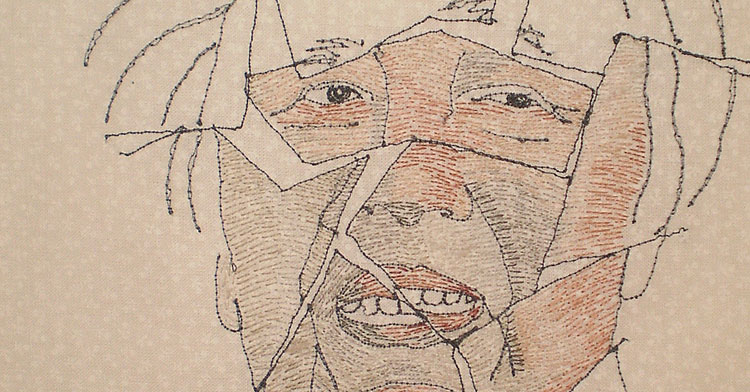

Building on the metaphors of my biomorphisms and realizing the complexities of vulnerability and power I interrogate areas of cultural tension. Contemporary issues like identity politics, institutionalized prejudice, corporal agency and substance use are incorporated into the processes and materials of what I build.

Wayward warp and weft

Tell us about your process from conception to creation

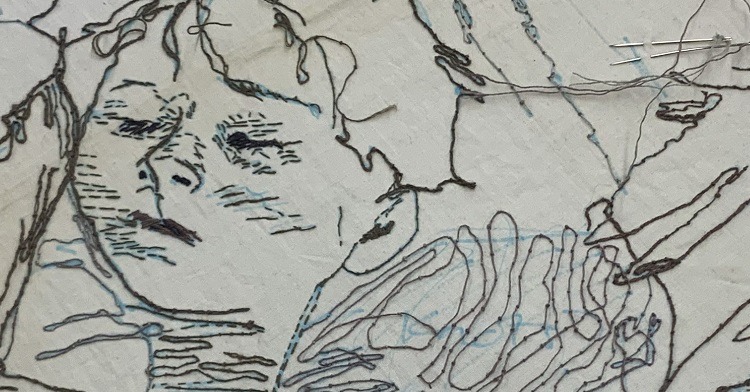

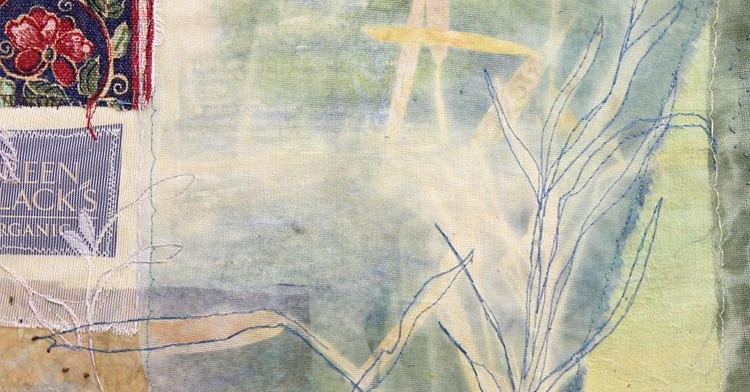

Materials inspire my ideas. Concepts inform my decisions. Playing with scale, how large or small to make an object, is important to my expression. To achieve large installations I often work in multiples that combine as building blocks into a monumental whole. This is process driven and durational with a constant eye for detail.

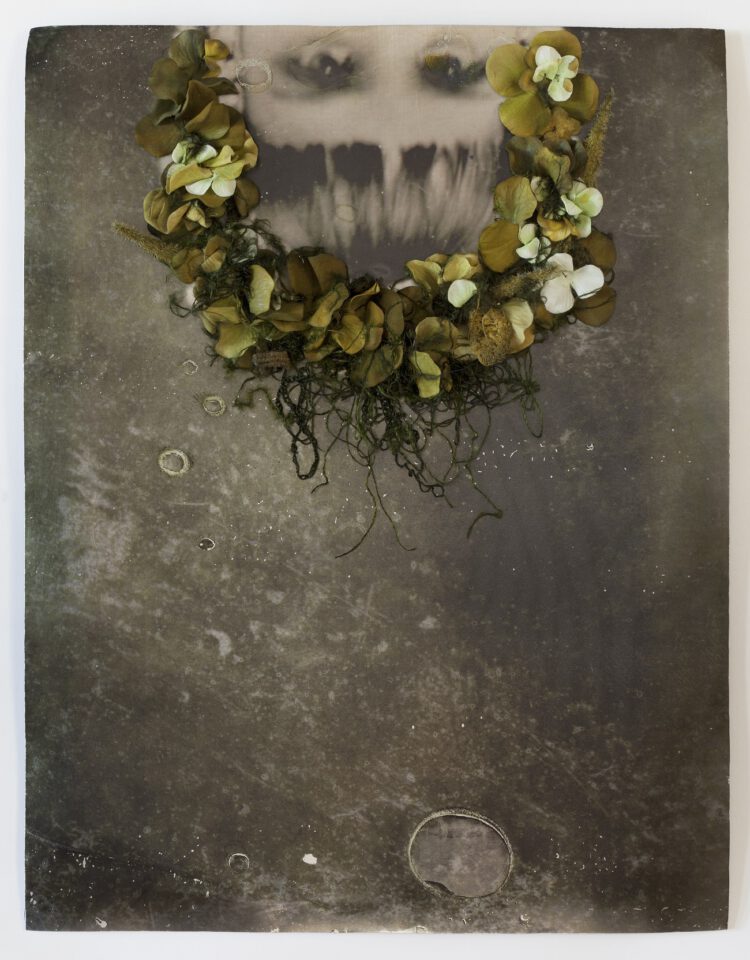

My favorite projects are those that respond to an inquiry, whether an invitation from a museum, a public artwork with an institution, or a personal investigation. Concept and message play a large role as well as how I process and choose materials. Call Me Rose is an elaborate headwear sculpture, sewn, embroidered and sculpted from gendered clothing remnants. It relates to the guise we present to the outside world and the meaning imbued in items of familiar dress form.

Many works begin in response to experiences and then develop. Time I spent living in a mud hut in Thailand captured my imagination when a small black scorpion haunted the drain of my bathroom sink and caused me great distress. It became a curiosity how a being so small could wield so much power. Once home, I found myself recreating this sentiment as Stinger, a 7×24 foot scorpion forged out of 9-gauge wire and appliqued doilies. It was while dyeing the doilies black that I was struck by the ambiguous domesticity and history of the makers. Stinger looms larger than life. Its lacy exoskeleton is collaged into a mosaic of patterns that now form the permeable body of a creature feared for its venomous sting and quick shift from repose to attack.

Tell us a bit about your chosen techniques and how you use them

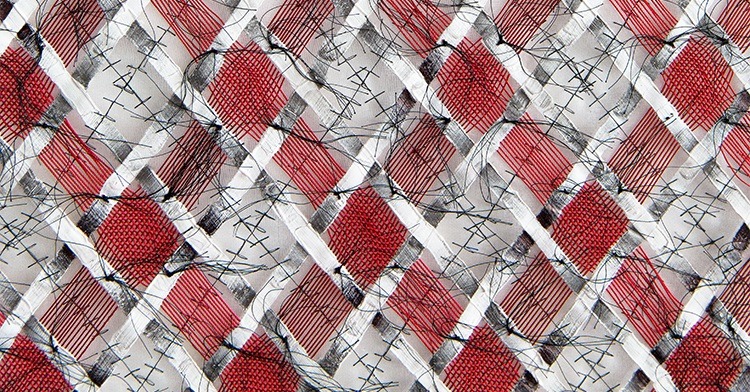

Throughout my career I’ve mastered the precision and complexities of many textile arts. Knitting, crochet, weaving, felting, dyeing, and embroidery are just a sampling of the dozens of techniques I work with and teach. I both employ and deviate from established doctrines to achieve a material aesthetic that conveys my feelings and meanings behind the work.

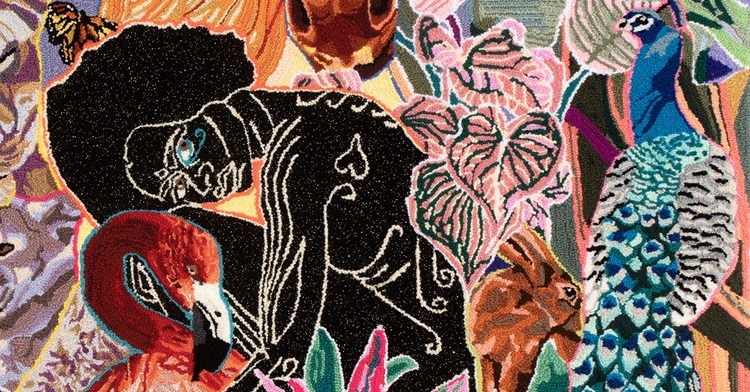

I bring an engineering mind to fabrication and am energized when learning other craft techniques and how to make things work. Evidence of the hand is present in all the missteps in warp and weft or wayward stitches. Random cross-hatched embellishing transforms surfaces into organic textures. Repetition, color and scale amplify message. Haptic qualities incite connection and cue the participation of community.

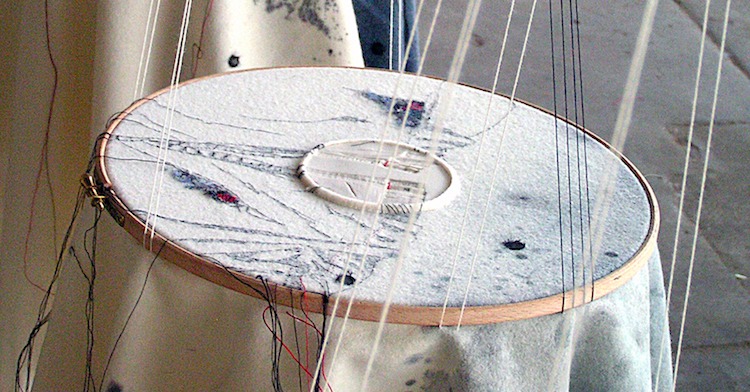

A favorite medium is community collaboration. Here the physical, psychological and social experience of working with others to recognize thoughts and feelings, to identify ideas in the absence of words, and to share identities provides a conduit for issues that are important to all of us.

In essence though, it is all about the comfort provided by slow methodical stitching to become mindful, and the assembly of multiples that create a ritual, quotidian practice to reinforce a self imposed control over an otherwise uncontrollable world.

What currently inspires you?

I’m drawn to the heritage of craft. The interweaving of tradition, creativity and politics as civic engagement that is nonmilitant and socially distant. I follow the practices of several movements including Craftivist Collective and The Social Justice Sewing Academy who bridge artistic expression with activism to advocate for social justice.

When teaching workshops, and in my FiberLab, I witness the fulfilment experienced by individuals while making and sharing. The emergence of self-expression and the desire for connection is palpable. It is exciting to have art as a vehicle that brings people together in body and spirit. My interactive public collaboratives yield similar sentiments. I’m inspired by the capacity of materials to innovate, employ process, amplify voices of the unheard and network the energy of many to foster community and effect change.

Intentional needlework

Tell us about a piece of your work that holds particularly fond memories and why?

Human Impact: Stories of the Opioid Epidemic brings together eleven artists working in craft-based media to explore the consequences of the opioid crisis through the lens of those who have been deeply impacted. To inform the creative process, the invited artists participated in substance use training by High Point Treatment Center, and then met with affected families for intimate conversations about their experiences with opiates. These informative actions were designed to inspire the commissioned works exhibited at Fuller Craft.

My piece, Once Was, is a memorial for all those lost to the opioid epidemic in the prime of their lives. This 12-foot, 2-sided tower is covered with 3,600 poppies that are stitched and then sewn onto a plush black velvet foundation. The poppies are made from repurposed clothing donated by those I spent time with talking about this project and the opioid crisis. The resulting array of patterns, colors, styles, and materials represents the lives of all people of every age, gender, relation, ethnicity, etc. The empty centers are outlined in bright red to embody the victims, and the void reveals black velvet beneath – a funerary symbol – adding gravity and symbolizing loss.

Once Was makes an impact on all who view it in person by effectively communicating the unfathomable numbers and tragic losses due to this crisis. I hope to raise awareness about the facts of the epidemic and highlight the need to offer aid to families in trouble, to initiate legislation to regulate the administration of pharmaceuticals, and to provide effective treatment for those who are actively afflicted.

How has your work developed since you began and how do you see it evolving in the future?

From the beginning, my work came from a very personal place. I created abstract organic objects inspired by my musings about cells and biological systems as metaphors for life. My themes revolved around emergence of self, growth/decay and hope. The material drove the content and the process was obsessive and meditative.

Since then my work has evolved in scope and technique. My use of needlework is more intentional. I consciously work to push the boundaries of traditional techniques to create works that imply an inner vitality and self-awareness. I use craft and materiality to convey concepts of contemporary relevance with a highly aesthetic appeal.

The trends of materiality, process and self-expression remain the same but with a larger focus on the magnitude of both content and physical space. I maintain an obsessive almost fetishist practice with an overabundance of stitches, multiples and actions to construct my devotional objects and installations. I continue to investigate new techniques and materials to push the potential of fiber as an art form.

What advice would you give to an aspiring textile artist?

Lose your fear and listen to yourself. Become expert at your technique and then deconstruct it. Experiment. Think through your choices of material and process making sure that they are relevant to your message. Meditate on your findings. Filter out external influences and voices. Yet at the same time seek out feedback from those you respect. Both positive and negative information is extremely valuable. Even if don’t agree you will find a voice in your disagreement.

For more information visit www.jodicolella.com

Did any aspect of Jodi’s work capture your imagination? Let us know how in the comments below

3 comments

Sara Ma

I was searching for inspiration and this article about Jodie helped me a lot.

Helen

I am currently deconstructing a technique/practice that I have had some success at so it was good to have Jodi’s affirmation at the end of the article – thank you.

Leanora

Thank you thank you again and again for this article. Very helpful and the work validates my art practice and life.