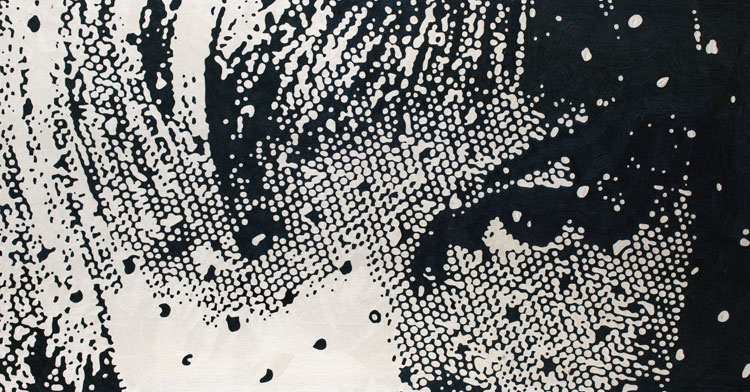

With her focus firmly on biodiversity and conservation, Kate Tume’s glittering, textured animal portraits are designed to catch the eye. Viewers are wowed both by a kaleidoscope of colours and her striking imagery. Texture, movement and sparkle come to life with exquisite surface embroidery and unconventional, layered embellishments.

Kate’s work explores the loss of regard for the natural world, which is leading to endangerment or extinction of thousands of species. She examines how colonialism and white supremacy create cycles of ecological desecration that negatively impact our society, environment and diversity of species with which we coexist. Kate also uses religious iconography and mythology to open a dialogue about what we truly hold sacred when it comes to our planet.

Remembering her childhood home filled with cross stitch designs, Kate rediscovered embroidery in her late twenties. She built her confidence by studying embroidery techniques but later chose to ‘unlearn’ them to free herself from rules and limitations. It’s a remarkable journey.

Memories of Cross Stitch

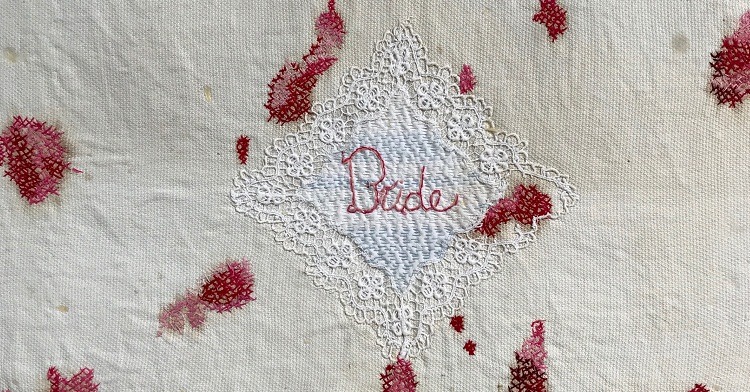

When I was a child, embroidery was the most visible creative endeavour around the home. My mum used to make counted cross-stitch kits, and the walls of my bedroom were decorated with her framed embroidery work. My great aunt Kora also used to do crewel work, so stitching is something that was in my family.

I remember always being fascinated by the different coloured skeins of thread and the pixelated pictures. I also loved the designer Jo Verso, and my mum had several of her books. I used to spend time looking at the different cross-stitch designs with all the little people, animals and plants composed of little squares. And the first cross-stitch I remember making used Verso’s designs to create an illustrated map of the African continent. I never finished it, and I wish I knew if it is still stashed away somewhere!

I think the familiarity of textiles, and ironically, a lack of confidence in my creative ability led me to using textiles. I was in a pretty low place and not happy with my life. But embroidery was one area I felt I had both ownership and an affinity. It allowed me to develop and grow my artistic voice.

Today, I feel the medium is incidental. I want my art to communicate and engage, regardless of the medium. I think textiles have a special ability to draw in the viewer. And they enable the audience to experience the art on various levels.

An artist’s journey

From a young age, I always wanted to be an artist, but various influences took me in another direction. It wasn’t until my late twenties that I built up the confidence to start trying art again. I had a corporate retail job that made me miserable, so I desperately needed a creative outlet. It took a few twists and turns, but I found my path by returning to my childhood roots.

I designed my first cross stitch using graph paper, tracing a skull from a copy of Grey’s Anatomy. I also started reading all the Royal School of Needlework stitch guides and taught myself techniques, including freehand embroidery, stump work and silk shading. One piece led to another.

Initially, I believed I could only make small pieces if I wanted to sell my work for a fair price for the time and labour involved. I made a couple of collections of art jewellery using stumpwork techniques, but eventually, I realised this was just another limitation I was placing on myself. In 2013, I decided to start speaking clearly in my own artistic voice, and I made my first large animal portrait, The God of Crabs. This led to a series of four more large pieces. A ten-piece collection followed that, and then six more in the next year. Ultimately, I had my first major exhibition in Brighton in 2017 as part of the events linked to the Remembrance Day For Lost Species that year.

Stitched activism

I am very committed to using my work as a way to explore and criticise systems of oppression. I want to draw attention to the subtle but intrinsic bias of accepted narratives around conservation and loss of species and their environments.

I think conservation today is very complicated, and messages that get popularised are often not the whole picture. Conservation needs to be intersectional and decolonised. It’s about caring for all life.

Inspiration usually comes in one of two ways: either I am drawn to an animal’s story, or their appearance inspires me to imagine how I can create it in textiles. I’m always on the lookout for new subjects, and I keep lists and save images of animals with interesting stories.

Most of my work is very much inspired by a story I have heard about an animal. Perhaps it used to be worshipped as a god by an indigenous community, but destruction of its habitat has now prevented those practices. Or it could be a beautiful or extraordinarily rare creature that has been hunted, almost to extinction, because of its beauty. I’m also inspired by real encounters I have had with animals, which leads me to research, and a project develops from there.

I used to look at my subjects through a fairly narrow lens of just the species and make work that responded to that. But a recent art residency really broadened my work to encourage more conversation and analysis. In particular, I feel very strongly about indigenous rights. Indigenous communities are, and have always been, land defenders. But despite being intimately connected with their environment, they are often the first to have their rights and voices oppressed.

Learning to break the rules

I am always on the lookout for new subjects. I keep lists and save images of animals with interesting stories. My creative process starts with a drawing. I find this essential, as it allows my brain to do some problem-solving and decision-making early on before I get to the fabric. And it helps me avoid making mistakes.

When I’m happy with my drawing, I photocopy it and enlarge it to the size I want, and then I trace it onto interfacing. If I’m making an apppliqué sketch, I might just cut out the drawing to use as pattern pieces for the appliqué shapes.

I next go through my fabric and embellishment drawers to collect a palette of materials. Chosen embellishments are then placed in tins around me while I work.

Once I frame up my ground fabric onto a one-metre-wide slate frame (I struggle to work small-scale these days), I start pinning down pieces. I really like using felt and velvet to make a collage, on top of which I can embroider or embellish.

After the groundwork is done, I work in sections. Sometimes I have a very clear vision for how to build my work, but I almost always change my mind about something as the piece develops.

I’ve become looser and more flexible as I’ve developed as an artist. I started out learning techniques from books and being quite rigid in their application, which helped me build up confidence. But the real growth has been in the ‘unlearning’. Letting go of rules and conventions often intrinsic to traditional learning of hand work.

My early inexperience and need to ‘get it right’ gave way to desire for expression. Now I use whatever techniques I like to create whatever I’m trying to express. That always means a lot of texture, dimension, high relief and movement. Goldwork, appliqué, surface embroidery and embellishment almost always make an appearance in my work.

Exploring masks

I was first inspired to make masks in 2017. I wanted to make death masks for extinct species, and I may still do that. I’ve never gotten to it because I worried it would take too long to step away from my regular art practice to try to figure it out.

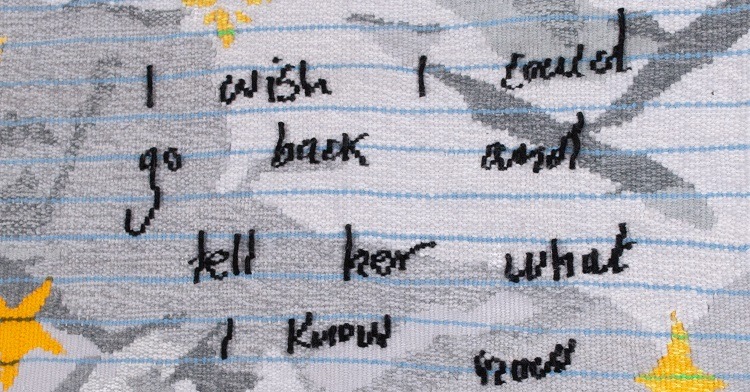

But now I want to explore them as a way to process my grief after my husband died in 2021. This event completely changed my life, and I found I had no interest in making the same kind of work as before.

Interestingly, I feel the pillars of my work have remained unchanged, but their application has changed. Grief, transformation and divinity are broad themes I’ve always interrogated. And narrative has always been extremely important to my work.

I am a storyteller interested in engaging the viewer and allowing them to have their own interpretation and stories about my work. Making masks is a deepening of that, along with the idea of being able to put a mask on and take it off. The viewer being able to literally inhabit the work feels central to my practice now.

The Portal Mask is the first mask I made. I am self-taught, so I thought about techniques I already had and how I could adapt them to make full face masks. Stumpwork techniques using wires made sense to me. I am so used to thinking about the specific order in which a piece of textile work is constructed to work. But now on my sixth mask, there have been refinements and tweaks along the way.

Portal is inspired by the symbolism of frogs and toads as divinities of death and transformation. I used padding to create dimension and drew on my many years of using embellishments and appliqué to create rich textures.

I had to think about at what stage I should insert the ribbon to tie the mask to the face and how to make the reverse side of the mask comfortable to lie against the face. I also had to make eyeholes part of the design and put them in the right place. And the weight of the mask also needed to be considered so it wouldn’t collapse. As a first attempt, it’s not a piece I’m too unhappy with!

Magical Mythical Omnipotent Child is my most recently completed mask. It’s my favourite to date. My creative process stands out as I was indeed very childlike in making it. I also went through a process in which the mask’s inspiration came to me rather than from me. It was channelled in some way. The ‘‘child’ revealed itself to me as I sat on the floor with pencils, cardboard and all my materials. As I started to draw the face according to what I thought I wanted it to look like, a whole other face came through that seemed to be more correct. As I normally have a very cerebral approach to my work, that freeness and going with the flow produced something that felt very progressive to me.

It also proved to be such a new and exciting way to work that I’m now following it as another new creative direction. For example, the mask I’m working on now came from a dream I had where I turned into a bat. I’m not interrogating the origins like I did before, so the deeper layers of meaning for the masks are then free to come to the wearer.

This mask was initially made from old cardboard boxes and gold and yellow items in my stash. I had thought it would be a golden mask using gold work, until I found an old piece of neon yellow gift wrap ribbon. The childishness of super acid-bright colours that clash, the expression of the face with a tongue sticking out (instead of my original plan for a smile) and the big ears with big earrings all spoke to a sort of divine child that I couldn’t wait to materialise.

What lies ahead

One of my favourite works is A Benediction, affectionately known as Benedict. His popularity has taken my work further into the world than any other piece I’ve made. When I made him, it felt like a departure, a threshold that has pushed my work a bit further. Indeed, I am very fond of him!

My work continues to develop, from the techniques I use to my depth of commitment and resolve to use art for activism. I want to be able to weave in more complex narratives and maybe work on an even larger scale. I’m always marrying the symbolic with the personal and transpersonal, and I hope to gain more success with that.

Comments