How would you describe yourself? For Leslie Rinchen-Wongmo, the words insatiably curious and cautiously adventurous characterise much of her life.

This proved to be a winning combination when, after buying a one-way ticket to India she became entranced by the colours, fabric and texture of the traditional Tibetan thangka (sounds like ‘tonka’).

These thangka, beautifully elaborate fabric mosaics, became a way for this previously meditation-resistant Californian to connect with Tibetan culture, as well as discover her own spiritual path.

Leslie’s four-year apprenticeship in a sewing room in the Himalayan hill town of Dharamsala – with the Dalai Lama as a neighbour – is an extraordinary story of how she became one of the few non-Tibetans to master the traditional art of silk appliqué thangka.

As she mastered this ancient artform, her own style of art evolved: blending Eastern techniques with modern materials and a Western colour palette. Today, Leslie is back living in California but she still draws on her love for Tibet and its people in her unique textile art.

Leslie Rinchen-Wongmo: I make sacred Buddhist images and portraits from pieces of silk stitched together by hand. My work is bold, textured, colourful, Asian-inspired and vibrant. It speaks to some and definitely not to others.

I am a caretaker of a sacred Tibetan tradition of textile art. I stitch bits of silk into elaborate figurative mosaics that bring the transformative images of Buddhist meditation to life.

Visually, I love the colours and the light and the three-dimensional textural quality. I also love the richness of symbolism and meaning in every form, and the connection of these forms to a great lineage of spiritual practice.

I love that the images I work with – the images of enlightened beings – have helped many people to become free of suffering and to teach others about their true nature. And I love being connected with a lineage of spiritual teachers and practitioners through these images and this sacred creative practice.

I hope that, in my small way, I can open people’s hearts with my work, that I can provide some stimulus or inspiration for their own awakening.

“I believe that beauty uplifts. So, I hope that the beauty of my artwork can open hearts and raise the spirit.”

Leslie Rinchen-Wongmo, Textile artist

Connecting threads

People often call this type of work ‘tapestries’ because they are fabric wall hangings. But I am not a tapestry artist. I do not weave.

Following a Tibetan tradition that goes back at least as far as the 15th century, I wrap strands of horsehair with silk thread and couch the resulting horsehair cords to silk fabric. Then I assemble pieces like a jigsaw puzzle into portraits and sacred images, all stitched together by hand.

You can watch me creating Green Tara in my short film Creating Buddhas, The Making and Meaning of Fabric Thangkas.

The technique is most often referred to as Tibetan appliqué but – unlike most appliqué – in this Tibetan method, there is no backing cloth to which pieces are applied.

Instead, pieces are overlapped and interconnected, held together by the elaborate connections between them. They do not rest on a single base. This is a beautiful metaphor for the Buddhist teaching of interdependence – nothing is absolutely true or existent. Rather each phenomenon arises in dependence on others, on relationships.

“In actuality, everything – including our ‘self’ – is always in flux and always interconnected.”

Leslie Rinchen-Wongmo, Textile artist

Cloth cultures

In my hybrid pieces, I’ve used quilting cottons, linen, photo-printed canvas and chiffon, and a variety of other materials.

For my traditional work, I use silk satins and brocades, mostly woven in Varanasi, India. Varanasi is a sacred Hindu city on the banks of the Ganges River in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. It is considered one of the oldest continuously settled cities in the world.

Varanasi is famous for its finely woven silk saris. Almost all the weavers are Muslim and live in the large Muslim quarter of the city and in outlying villages. While most of these weavers create the saris worn by women all over India, a few make the fine brocade and satin from which Tibetans stitch thangkas.

The heavy silk satin and brocade produced by Indian Muslim weavers is not for themselves, nor for the Indian Hindu culture that permeates the city, but for Tibetan Buddhists from the mountains. These disparate cultures have been woven together in silk for generations.

“The satin has a particular buttery quality that allows large needles and thick horsehair cords to be pulled through without breaking threads or leaving holes.”

Leslie Rinchen-Wongmo, Textile artist

The role of thangkas

The Vajrayana or Tantric form of Buddhism practised in Tibet uses imagination to harness emotional energies and achieve speedy liberation from the misconceptions that cause suffering.

Practitioners deliberately cultivate their imaginations with images of enlightened beings, pure lands, flowing blessings, and generous offerings. In visualisation, divine figures arise from emptiness like a rainbow and dissolve again into space. Although they may appear external to us, they always merge with us in the end.

The point of all these practices is to move us from a muddled relationship with reality to a relationship based in awareness.

“Thangkas serve as models for the intangible yet infinitely impactful images you can conjure in your mind’s eye to free yourself from distorted and limiting mindsets.”

Leslie Rinchen-Wongmo, Textile artist

The figures that grace thangkas are expressions of awakening, of fully realised human potential in honest relationship with the world as it is. They are personifications of teachings and practices in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition. Their multifarious forms highlight a vast range of awakened qualities: Avalokiteshvara embodies awakened compassion, Manjushri breathes awakened wisdom, Vajrapani radiates awakened power, and so forth.

These divine figures are collectively referred to as lha in Tibetan, and generally called deities in English. However, referring to the figures as gods and goddesses is a misleading use of words. They are, in fact, buddhas, that is, awakened beings. As embodiments of our own true nature, their only purpose is to liberate us from ignorance and suffering.

While each form has a speciality, based on vows they made when they were ordinary beings like us, each also encompasses the full spectrum of awakened potential. They don different guises to suit people’s diverse temperaments. Every deity in the Buddhist pantheon exists to assist us in generating wisdom and compassion to become free from endless cycles of dissatisfaction and suffering.

Stitching as meditation

Making a thangka is like sharing quiet time with enlightened beings and sages. That is, people who have recognised the true nature of things; people who act out of pure compassion; people who have overcome all negative motivations and reactions.

Stitching a thangka is like hanging out with the best of my human potential and with the possibility and promise of awakening. We sit together, pass time, and share tea.

“As I stitch, I become steeped in their fragrance, tinged with their colours, and I feel the presence of enlightenment touching me.”

Leslie Rinchen-Wongmo, Textile artist

The Tibetan word for meditation, gom, literally means to familiarise or habituate. In some meditation practices, we sit with a specific heart-opening quality or inquiry, allowing it to permeate our mind-stream and allowing ourselves to become familiar with it.

Thangka-making acts like this too. Not only does the work arouse focused attention, it also engages the artist in a nonconceptual relationship with enlightenment, compassion and wisdom, while placing attention on just this stitch.

In class every morning, my teachers used Buddhist philosophy to open windows of freedom in my conceptual mind. In the sewing workshop every afternoon, the deities infused non-conceptual understanding in my heart, in my fingertips and in my bones.

Rather than memorising lists of symbols and meanings, stitching invited me to hang out with the best of myself. On some unspoken, unanalysed level, I knew that these figures embodied the most potent and potential-rich aspects of my own being. I hoped that a little bit of their goodness would rub off on me.

The road to Dharamsala

I remember sewing clothes at home occasionally as a child with my mother’s guidance. In college, I became interested in Amish quilts. I was drawn to the bold colours, clear shapes, fluid fabric and meticulous handwork. I started to learn quilting but was interrupted, first by a herniated disc in my back and then many years of other activities.

I saw the Dalai Lama on his first visit to the US during my first year of college. He made a strong impression on me, but I wouldn’t have called myself a Buddhist.

Toward the end of college, I did some quilting. I dropped it for a while, and then ended up in India, getting to know the Tibetans and delving more deeply into Buddhist philosophy. There, I found Tibetan appliqué and felt a wonderful sense of connection as two strands of fascination became intertwined.

“I fell in love with the colours, the fabrics, the texture and the connection with my spiritual path – I just had to start stitching again.”

Leslie Rinchen-Wongmo, Textile artist

In 1992, while serving as an economic development volunteer for the Tibetans, I saw my first silk thangka in production.

One day, as part of my volunteer work, I joined a tour of Tibetan handicraft centres. When I walked into a sewing workshop at the Norbulingka Institute, which was still under construction, I fell head over heels in love with the pieced silk images I saw there.

I was completely entranced by their colour and beauty. I was also captivated by the integration of Buddhist teachings with such extraordinary handicraft. The threads of my life seemed to be coming together. I immediately wanted to learn this art, having no idea that my life would take a completely new trajectory from that point.

In the sewing room

Soon after, I found a teacher – and then another – and set my life in a whole new direction. I entered a full-time traditional apprenticeship with a Tibetan master. Working alongside several young Tibetan women who didn’t speak any English, day in and day out for four years, I learned to stitch like the Tibetans and create these vibrant sacred images.

People often imagine that thangkas are created in a solemn and meditative environment. Perhaps in some places that is true. But my own experience in a fabric thangka workshop – as well as what I saw among thangka painters in Dharamsala – is something much more integrated and natural and seamless.

“The makers are not detached from worldly life but rather, channel all the energy and vivacity of worldly life into the creation of beautiful supports for spiritual practice.”

Leslie Rinchen-Wongmo, Textile artist

In the tsemkhang or sewing room, I sat around a big table with eight to 10 young Tibetans. Conversation was lively: gossip, laughter, camaraderie.

We listened alternately to traditional Tibetan folk music and to dance tunes by Madonna and Michael Jackson. Butter tea and Tibetan cookies (sometimes the offerings left from a recent ritual in the temple) were served mid-afternoon. It was a joyful, friendly, relaxed environment.

My Tibetan was pretty good, but not good enough to keep up with active group conversations, so sometimes I retreated into my own thoughts and sat quietly as I stitched.

Practice, practice, practice

We worked as a team on large projects. Genla (teacher) Dorjee Wangdu selected pieces of the design that were appropriate for each student’s level of skill. He transferred a section of the design to silk and handed it to an apprentice with instructions as to what colour and line weight to use.

We sat on cushions around a big table – or, when appropriate, at one of the many treadle sewing machines in the workshop – and worked on our assigned pieces. When we’d finished, we returned to Genla for comment and for our next assignment.

The teaching method was straightforward: learn while doing. Working on big projects like this allowed us to get lots of repeated practice on each step.

“When I finally learned to embroider eyes, I spent a year practising only eyes.”

Leslie Rinchen-Wongmo, Textile artist

The time-consuming nature of creating these patchwork thangkas has always made them significantly rarer than painted thangkas. For this reason, they are considered by Tibetans to be especially precious.

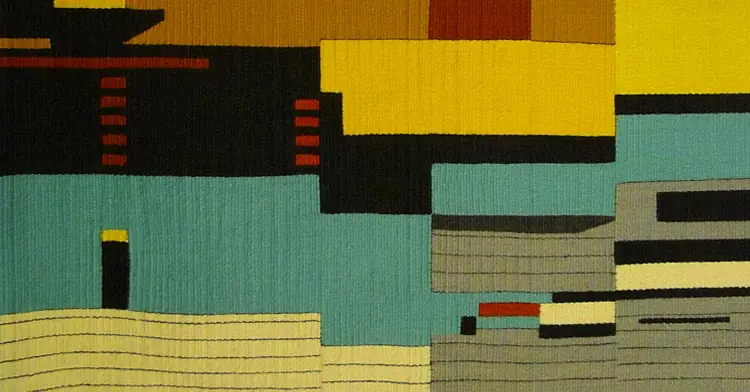

East meets West

During my apprenticeship, I learned to create traditional images out of silk. However, I soon realised my colour sense was different from that of the Tibetans – slightly more muted, with more jewel tones and fewer primary colours.

I also leaned toward simplified backgrounds and highlighting the central figure. This was partially due to aesthetic preference and partly because these thangkas take so long to produce that simplification was essential if I was ever to finish anything.

Over the years, I began to combine the traditional techniques I’d learned in my apprenticeship with inkjet printing and machine quilting, to create fabric portraits of real people in the Himalayan Buddhist world. I feel a mysterious kinship with Tibetans and their culture so, even in my non-traditional, non-thangka work, I play with imagery from that part of the world.

“As I incorporate new fabrics and machine quilting into my sacred works, evolving the traditional thangka form, I take care to respect and honour the qualities of the sacred images themselves.”

Leslie Rinchen-Wongmo, Textile artist

Developing my style

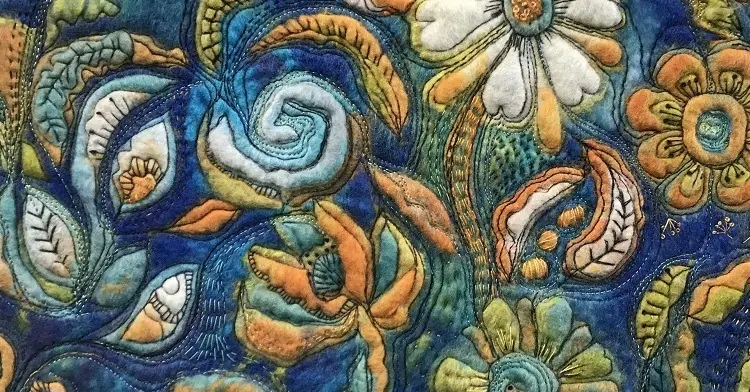

My ‘hybrid pieces’ fall broadly into two categories. First, traditional figures in quilted and/or printed surroundings (with idealised images of enlightened beings rendered in traditional Tibetan appliqué), such as Chenrezig and All In This Together. The figures are stitched by hand and their form is true to tradition, but the backgrounds and borders are machine quilted and sometimes embellished with printed words.

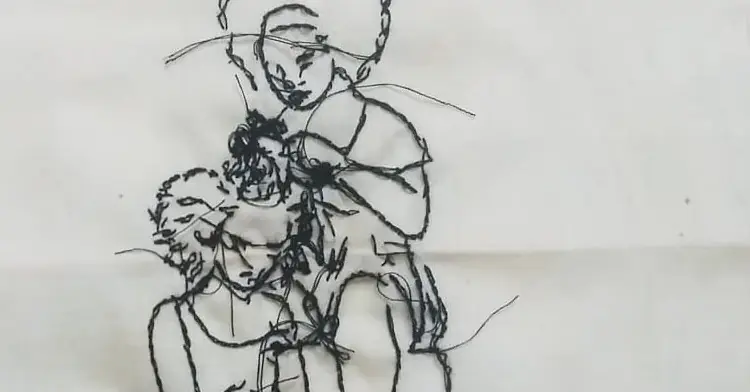

In the second category, I’ve departed from traditional imagery and used a combination of quilting, printing and Tibetan appliqué techniques to create fabric portraits based on photos taken by friends.

The first of this type was Three Mongolians. I became inspired when I saw a photo taken by a friend while on an architectural study tour of Mongolia. I was still in my apprenticeship learning to make fabric thangkas. I fell in love with the three figures in the photo and noticed they were wearing clothes that were made of the same satin I was learning to use to make thangkas.

I immediately imagined these figures in fabric, but ten years passed before I got my hands on the photo and was able to make this completely hand-stitched piece. I projected the photo onto a wall and traced its outlines and the lines on the people’s faces. As I stitched those faces, I was very nervous and uncertain about how they might turn out.

I had no idea whether it would be successful and was happily surprised by the result. For me, these three characters remain in perpetual lively conversation, and I know they bring great joy to the woman who ultimately bought the piece. Faces Of Pilgrimage and Pool Of Light incorporate photos by a dear friend, Diane Barker, whose photographs of Tibetan nomads can be seen in her book, Portraits of Tibet. With Diane’s permission, I printed her photos and applied hand-stitched fabric renderings of the figures onto the photo-printed fabric. This brings the figures to life as if they’re emerging from the photo.

Healing stitch

I started stitching a Medicine Buddha when my mother was in treatment for cancer, and many friends and loved ones were encountering health problems and loss. Each stitch was dedicated to their well-being.

When my mother recovered, I paused the work as I’d become indecisive about the background. I didn’t feel like moving forward with my original design but I wasn’t quite sure how to change it. I put the completed Buddha figure aside for a while to ponder and ended up leaving it undone for several years.

I finally returned to it during the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic while we were all sheltering at home. The world clearly needed healing, and our interconnection was so tangible at that time.

“Spurred by the global pandemic to return to this thangka, I felt like the clouds and mountains wanted to offer the whole earth to the Buddha for healing.”

Leslie Rinchen-Wongmo, Textile artist

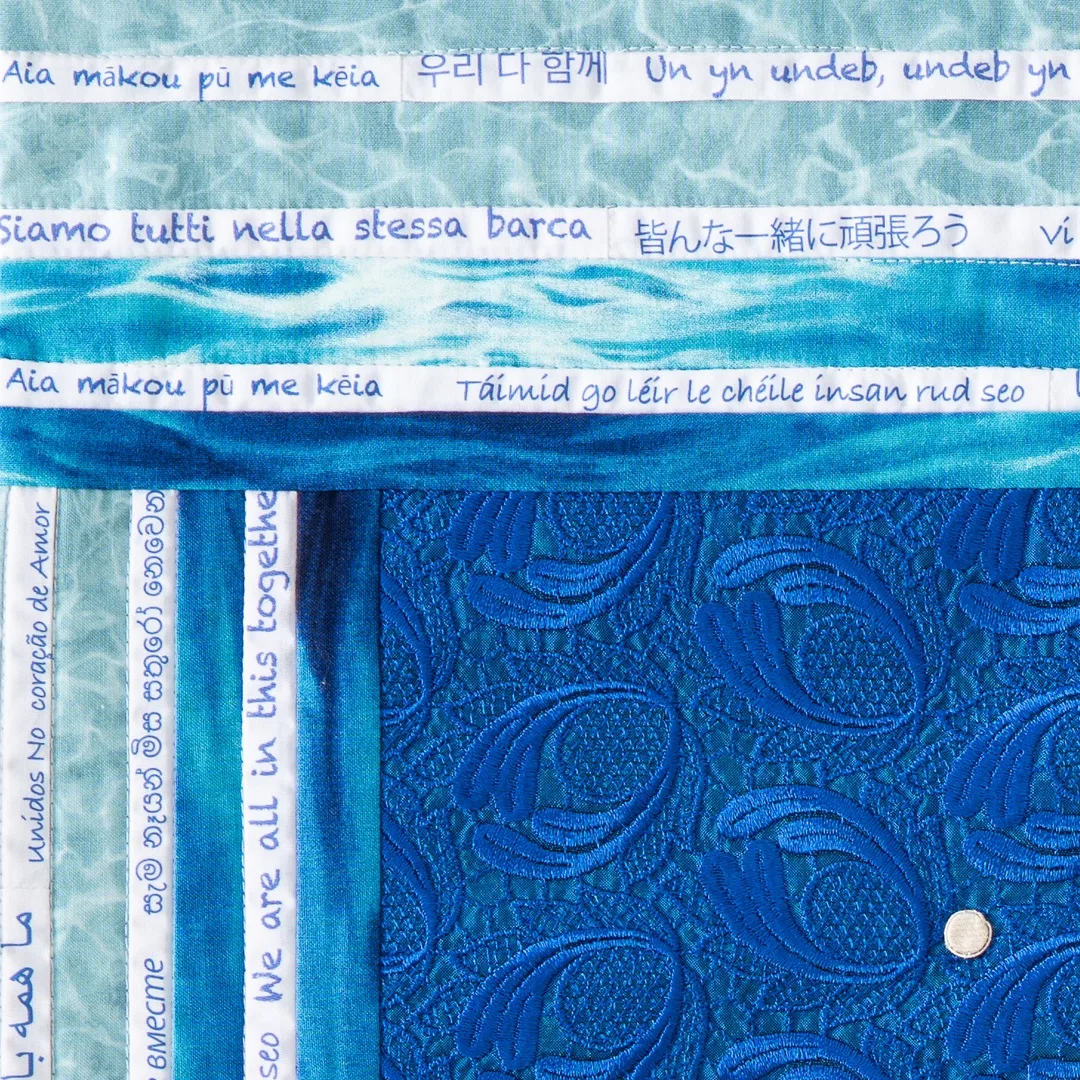

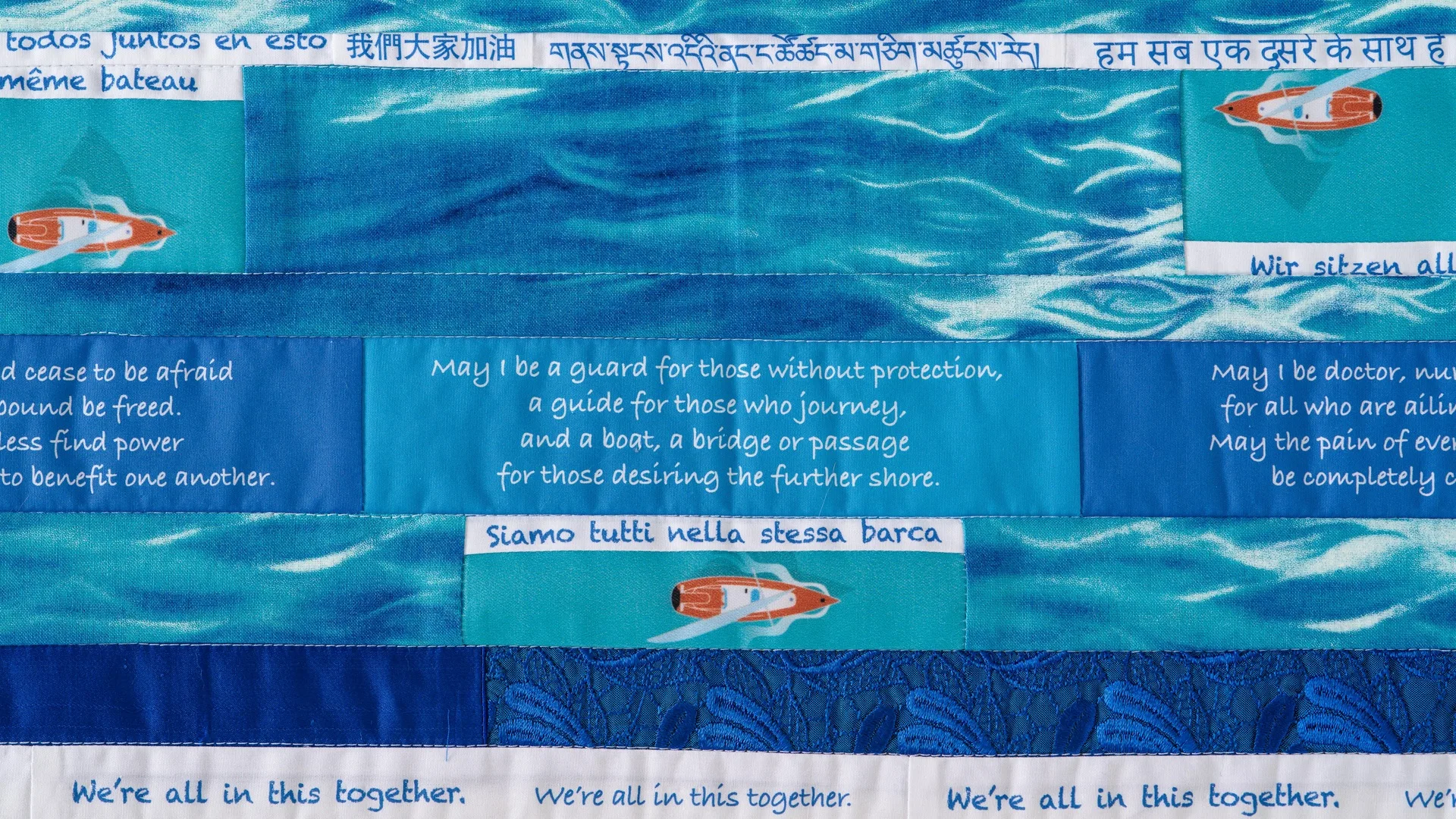

I became acutely conscious of global interconnection. The phrase ‘we’re all in this together’ kept coming to mind.

At the same time, I was aware that different people were experiencing significantly different impacts from the shared crisis – depending on their work, health, race, socio-economic conditions, as well as whether they live alone or with others.

The virus interacted with imbalances at our roots. Tibetan medical practices are based on the premise that disease arises from physical imbalances caused by the mental poisons of ignorance, attachment and aversion. True healing must, therefore, be grounded in spiritual transformation.

Buddhas are referred to as great physicians because they possess the compassion, wisdom and skilful means to diagnose and treat the delusions that lie at the root of all suffering.

One world, many voices

I reached out to friends all around the world asking how they would say, ‘We’re all in this together’ in their languages. I printed their responses on strips of cotton and created a border of their words, surrounding the Buddha with voices from around the world – 28 languages in all – expressing the unifying truth that we’re all in this beautiful, muddy mess together.

It was deeply gratifying. Alone in my home studio, I felt like friends around the world were collaborating with me.

Many offered versions of ‘we’re all in the same boat’. This reminded me of the traditional Buddhist metaphor comparing the cycle of lives to an ocean, and our human body to a boat that can cross this ocean of suffering to the other shore of clarity and freedom.

I printed, stitched, and quilted the words into a watery border representing the ocean of samsara in which our diverse experiences arise. Below the Buddha, I included a prayer from the great Buddhist commentator Shantideva.

The thangka quilt All In This Together has been travelling around the United States for two years in the Sacred Threads travelling exhibition.

“May the frightened cease to be afraid and all those bound be freed.

May the powerless find power and all beings strive to benefit one other.

May I be a guard for those without protection, a guide for those who journey,and a boat, a bridge or passage for those desiring the further shore.

May I be the doctor, nurse and medicine for all who are ailing in this world.

May the pain of every living creature be completely cleared away.”

Shantideva, Buddhist commentator

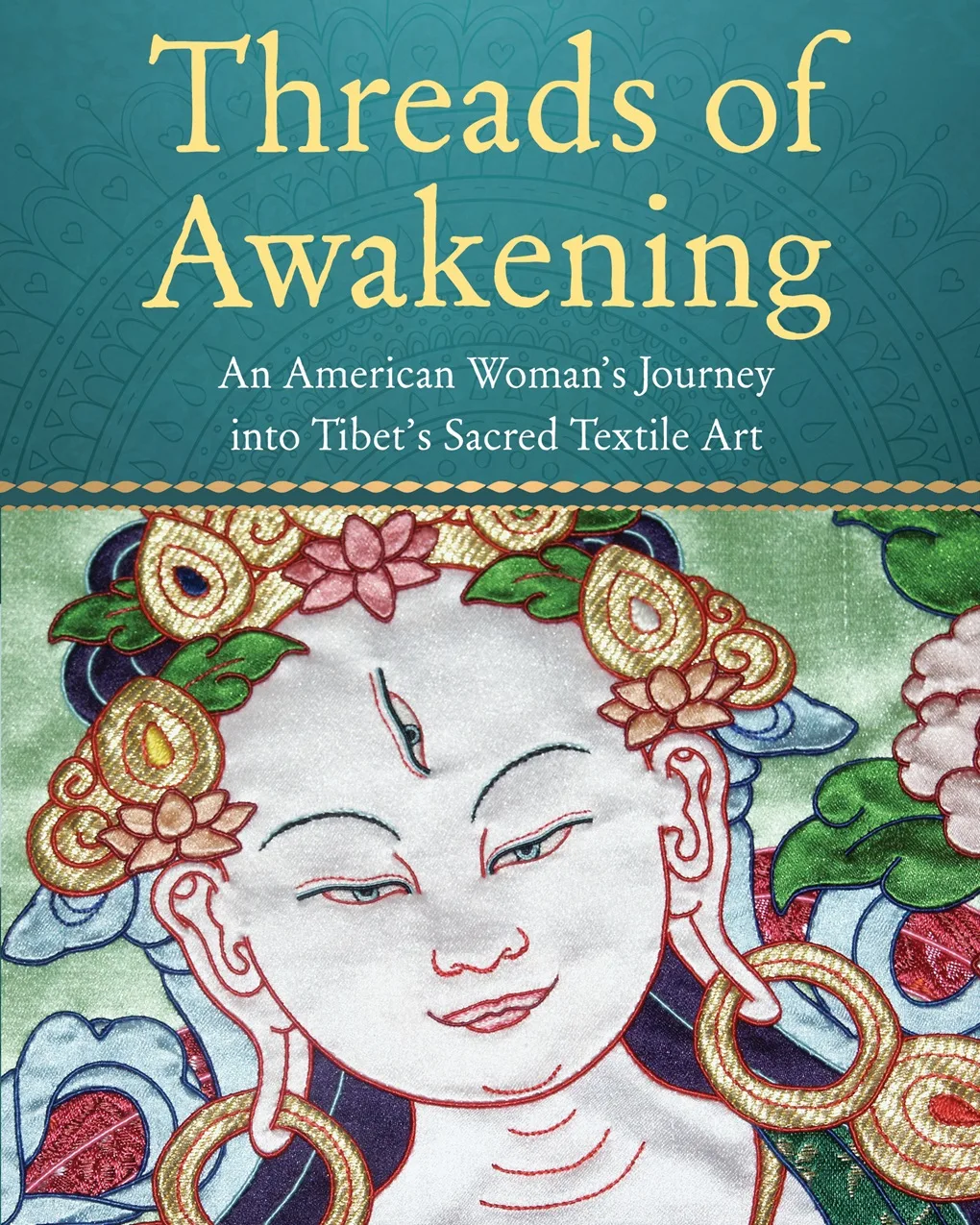

Documenting tradition

Early in my apprenticeship, I realised I was uniquely positioned to write a book about Tibetan appliqué thangkas. There are no books on this art form in any language, just a few articles and a paragraph or two in books about other Tibetan arts.

As an English speaker with uncommon access to a little-known precious tradition, I felt a responsibility and a debt of gratitude to my teachers to document the form. It felt like a life assignment that I would need to fulfil one day.

I really don’t love writing – for many years I preferred making art over writing about it. Then, for another several years, I thought I needed to get some formal education in art history so that I could trace the art form’s origins and speak on it authoritatively. I looked into advanced degrees but was discouraged by a couple of professors from taking that path.

Finally, I realised my direct experience was the most accessible and interesting way to approach the topic.

I started writing my memories of apprenticeship: of the tsemkhang or sewing workshop, of life in Dharamsala, and of my experience making specific thangkas. The story gradually took shape over the next few years and was published as Threads of Awakening: An American Woman’s Journey into Tibet’s Sacred Textile Art, in 2022.

I’m proud that I actually wrote and published a book that documents and honours the tradition I inherited. After two decades abroad, I now live in southern California near the beach with my three cats and enough fabric to last several lifetimes – but never enough for the next project.

I’m now in a period of transition, open to daily inspiration and listening for clues as to what I’ll create next.

Comments