When she’s not in her studio, Lindsay Olson can often be found canoeing with her husband on one of Chicago’s many waterways. It was through this intimate connection with watery places that her love of science was awakened.

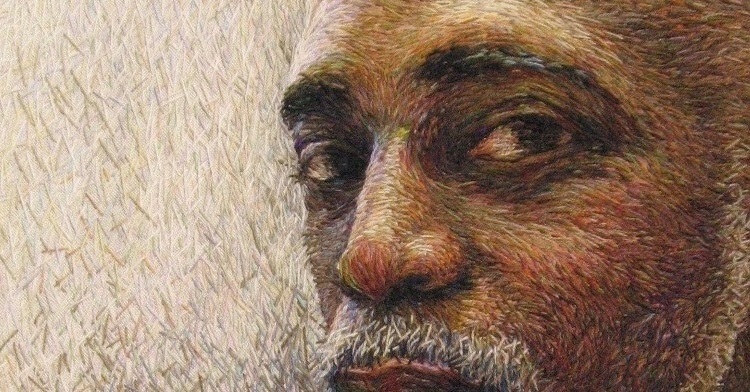

Lindsay is an artist with a science-based practice. Partnering with scientists and laboratories, she learns how science supports our modern culture, and then translates what she discovers into embroidered textile art.

Through a residency with The Wetlands Initiative, Lindsay gained new knowledge about restoring wetlands and the associated increases in biodiversity. She produced a collection of symbolic stitched artworks, intriguingly inspired by King Tut’s burial collar, to share her findings with the wider world.

Lindsay’s art elegantly communicates the hard work and ecological concepts behind this wide-ranging wetland restoration programme. And she demonstrates that art belongs everywhere, even in the world of ecological and environmental science.

Sharing science through art

Lindsay Olson: My studio practice has three phases. The first stage involves conducting research. For this residency, as well as completing my own visual research, I worked in the field to understand how wetland restoration works.

Armed with this new knowledge, the next phase is to develop accessible art. In the final stage of all my projects, I use my work to help others understand the science I’ve learned. I want to communicate to the world that science is a key part to creating a more vibrant, just and climate-friendly world.

Through my projects, I aim to create a partnership – in this case, helping others to appreciate the value of the work done by The Wetlands Initiative (TWI) – while promoting the value of fine art as a tool for science communication.

Once, an exhibition attendee said to me, ‘I came for the art and was surprised to learn about the benefits of wetland restoration.’ And on the art side of things, I often hear scientists say that mine is the first work of art they have felt a genuine connection with.

“I’ve found it a very powerful experience to discover that I can learn complex science using my training as an artist.”

Bringing together these two areas of investigation – science and art – is very satisfying. I hope the joy of discovery and the deep pleasure of creating textile work shines through the pieces I make.

I created a pitch outlining how my previous art projects (with Fermilab, the University of New Hampshire Center for Acoustics Research and Education, and the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Chicago) were used in dozens of exhibitions, articles and speaking engagements to connect the public with scientific research. I cold-called the President and Executive Director of The Wetlands Initiative, Paul Botts, and found that my approach perfectly fit with his desire to expand the awareness of this organisation.

From the very first day of my residency, every member of the TWI staff supported me, with encouragement, information and invitations to work beside them in the field. For example, to help share my plans, they produced an introductory video outlining my work. This has been a very rich experience for me and everything I could hope for in a successful partnership.

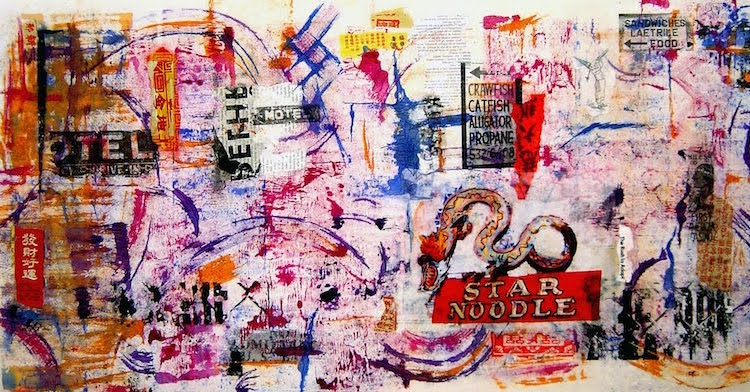

Wetland restoration

This project began with a previous project Land and Sea: Intimate Connections. I live in the Mississippi watershed, which feeds into the Gulf of Mexico, and learned that land uses, such as modern intensive farm practices and urban wastewater discharge, are responsible for excess nutrients running into the waterways. This results in profound disruption to the ocean ecosystems in the Gulf of Mexico, including toxic algal blooms. Two powerful strategies for reducing nutrient run-off from the land are to plant cover crops, to protect and fertilise the soil, and to restore native wetlands or, in the case of TWI, engineer them from scratch.

Digging a little deeper, I came across the work of The Wetlands Initiative (TWI), which was founded in 1994 to design, restore and create wetlands in Illinois and Northwest Indiana. This organisation innovates, collaborates and employs sound science to improve water quality, wildlife habitats and our climate. TWI envisions a world with plentiful healthy wetlands sustaining biodiversity and human well-being. Using engineering prowess, a deep understanding of ecology, and collaborative partnerships with like-minded conservation and community groups, TWI has restored thousands of acres of land back to working wetlands.

The broken circle

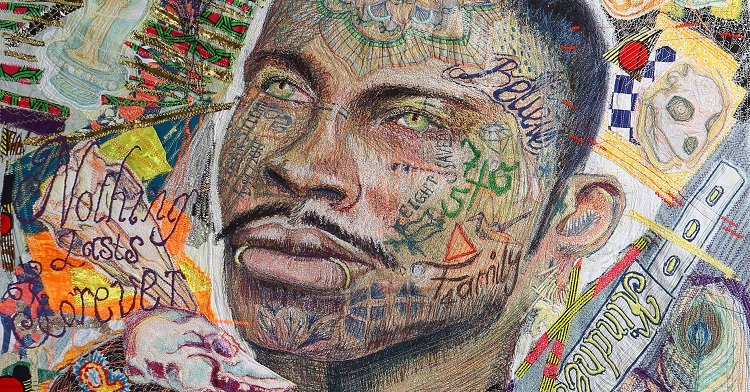

Early in my visual research for this project, I came across a 3000-year-old floral collar that was buried with King Tut, part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection. I was familiar with ancient Egyptian jewelled collars seen in images of kings and queens. What I didn’t know is that we’re not the only people in history to use fresh flowers to honour our dead; members of ancient Egyptian royalty were buried with elaborately fashioned fresh flower collars.

“I’ve been exploring the design possibilities of a circular format for a long time.”

Collars seemed to express a broken circle perfectly and act as a metaphor for the broken cycles of nature we humans have wrought upon the land. The shape also references the ways in which we use our understanding of ecology to restore remnant wetlands. I decided to use this symbolism to suggest a very personal connection between viewers and the wetland restoration programme.

The other intriguing connection to the project is that the funeral collars are, in intent at least, an opulent garment intended to be worn by royalty in the afterlife. The time-consuming processes I use, including embroidery, quilting and beading, are a way to denote luxury and elevate the subject matter.

Muddy boots

On my first day working with The Wetlands Initiative, I found myself standing in the bright June sunlight in the Little Calumet River corridor. Wetland restoration begins with controlling the hydrology, and water control structures are installed to mimic the natural hydrology of this region. I was helping the crew to install water gauges that measure the ebb and flow of water in the site.

I listened to the discussions between TWI’s senior ecologist, Dr. Gary Sullivan, the Calumet Coordinator, Harry Kuttner, and Geospatial Analyst, Jim Monchak, about last season’s eradication of invasive Phragmites reed grasses and the planned planting of seedlings. In the background, the drone of the road traffic blended with bird calls and buzzing pollinators. This place was alive with energy, and not just the kind pulsating through the electricity pylons above our heads. At my feet were rattlesnake-master, hybrid cattail, hardstem bulrush and sweet flag. These plants were thriving in the space created by the removal of invasive species the previous year.

“Having nearly fallen in the muck that morning, I realised I was falling hard for wetland fieldwork in general, and this region in particular.”

An expansive restoration programme was already taking root here, in the heart of the Rust Belt. Industrial development had reduced the Calumet region into a patchwork of declining wetland areas. In partnership with other organisations, The Wetlands Initiative has already achieved huge gains in healing some of these damaged ecosystems, returning them to welcoming, publicly accessible natural and biodiverse areas.

Biodiversity

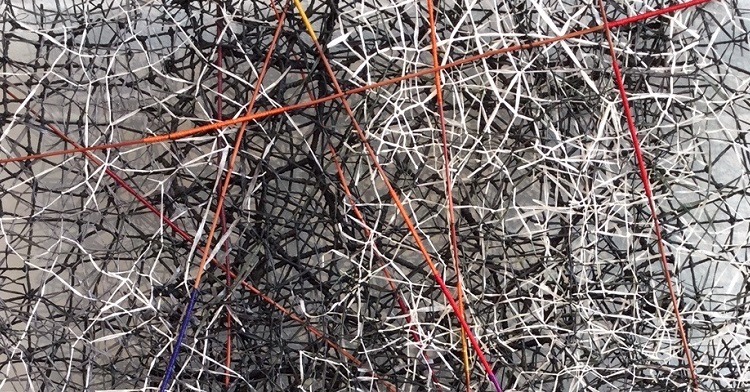

In my artwork Calumet I, the central theme is the creation of hemi-marsh conditions, where there is an equal mix of open water and emergent plant growth. Contours of the different marsh depths are the foundation of the design.

Working alongside the crew, I learned about the importance of hemi-marsh habitat. TWI works to re-sculpt the land and control the hydrology in these isolated parcels of wetlands that are no longer connected by natural water dynamics. Their aim is to mimic nature and allow the wetlands to function properly again, to clean the water and support a diverse group of plants, insects, animals, birds and microbes.

I also discovered that muskrats are key partners with TWI in their restoration efforts. When the right water conditions are restored, the hemi-marsh is created primarily by the muskrats, which create openings in the vegetation. They cut down marsh vegetation in characteristic patterns to create their homes and build feeding platforms.

Choosing materials

The colours, techniques and elements I chose reflect the challenges faced today and a vision of the future of these wetland jewels-in-the-making – depicting this quiet revolution in restoration and land conservation. It’s unexpected to see elegant art made about what was previously an industrial landscape – this incongruity attracts the viewer to take a closer look.

Working with a circular format, I designed a collar to be roughly human-sized, a scale chosen to help the viewer relate to the work. Developing just the right ‘squashed’ circle that flowed in a graceful arc was the foundation of the work.

“I take the time to understand how the materials I use support what I’m learning and the scientific information I want to convey.”

Using Italian batiste as an underlayer, I selected quilting cottons for the ground fabric and collage elements. For the embroidery, I only use DMC thread as it comes in a large variety of colours and can be used in both six stranded and perlé cotton threads. I also know I can trust DMC thread to be completely colourfast.

I experimented with a couple of embroidery frames when creating the collars. I tried out the Millenium frame, reviewed by Mary Corbet of Needle ‘n Thread. I also tried out a traditional slate frame from Ecclesiastical Sewing that was custom made for the size I needed. I really enjoyed working on both frames, but found the traditional slate frame held the work under tension more consistently over time.

Sketching in the details

In the early phases, I’m constantly shifting between creating art and learning science, and I do a great deal of sketching and sampling. I drew all the plants and the components I wanted to include, cut them out and arranged them around the collar template. Then I transferred the designs to the ground fabric using an air-erasable pen.

In Calumet Region I, I stitched the flora found in a restored hemi-marsh, including American lotus, sneezeweed and marsh marigold. The small fabric squares suggest the scattered disconnected nature of remnant wetlands. Untangling the ownership of these parcels of land is complex, requiring patience and persistence.

In Calumet Region III, in the lower part of the collar, I embroidered the names of American Indian tribes to acknowledge that these are the homelands of the Potawatomi and dozens of other Native tribes. Nearly half a million tribe members make their home here in the Upper Midwest region.

For the colours, I found myself tilting unconsciously toward the colours I had seen in my fieldwork. I started with about 50 colours of quilting cotton and eventually settled on a palette. Nature is a terrific inspiration – looking at my art and alongside the photos of TWI ecologist Dr. Gary Sullivan (whose photographs of restored prairies were exhibited with my work), all the colours flow harmoniously together.

“One exhibition visitor remarked that my artworks made her feel calmer – this emotional connection and response is something I’m looking for.”

Peering into a treasure chest

The framing was an important consideration. I chose a silver-framed shadow box to hold the artworks, creating a kind of ‘treasure chest’ display.

“Through this high quality presentation method, I am honouring the significance of this restoration programme.”

In speaking with the framer, we discussed their price for stitching the artwork to the background fabric. In the end, I decided to cut collar-shaped foam core shapes and attach the artworks myself. This meant that the framer was able to glue the work to the background easily. By doing this, I was able to save money on the framing process, while also making the collars stand out from the ground fabric to give a more refined presentation.

Knowledge motivates

Throughout the process, there’s a lot of fumbling around in the studio. It takes many hours of planning to determine just the right expression of an idea. I always aim to avoid the heartbreak of ripping out hours of stitching in order to move something to a better position.

There’s some frustration in the beginning of a project because I deliberately create an uncomfortable situation. Artists generally appreciate complete freedom in making art but somehow, for me, the limits of creating art about science is a necessary constraint for awakening inspiration.

“I knew nothing about wetland restoration and oddly enough, this discomfort provides a kind of creative friction, ultimately leading to an outpouring of inspiration.”

I often feel like I’m inching along with the science and art together. Switching from learning the science to creating the art. If I get stuck in one or the other area, switching helps me to feel less frustration.

I love the process of stitching and the pace of the work, the movement of the needle, and the tactile experience of handling fine threads and fabric. This combination becomes a meditative activity. Because the work moves forward slowly, I have plenty of time to think about the science I am learning. I’m remembering the smells in the field, snippets of conversation between staff members, and I’m always looking at my sketches and remembering the work we did together in the field.

Dixon Waterfowl Refuge

The crowning achievement of The Wetlands Initiative is the work they have accomplished over decades in the Dixon Waterfowl Refuge. After more than a century of industrial agriculture, the area has been transformed. It is bursting with migrating and resident waterfowl, an ever increasing diversity of plants and insects, and the occasional fisherman.

One of my favourite days in the field was participating in a pollinator blitz in the summer of 2022. The data we collected that day on the butterflies, moths, bees, wasps, beetles and other creatures, to measure ecosystem quality as the project moves forward. A sharp-eyed staff member, Vera Leopold, even sighted a ruby-throated hummingbird.

In the artwork created in response to this experience, I’m creating references to the fact that land was in heavy cultivation for over a century. The squares along the bottom reflect the farm plots. And the identical stitches express the monoculture of industrial farming. But these references fade a bit into the background, so the pollinators can take centre stage.

Midewin Prairie

The Wetlands Initiative group is also working at Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie. The prairie consists of a mosaic of interdependent habitats, including sedge meadows, oak savanna, mesic prairie and, perhaps surprisingly (for a habitat often perceived as well-drained grasslands), wet prairie. This project highlights the idea that wetlands belong everywhere. Water always seeks its level, whether it’s running down a mountain or flowing towards a gentle depression in the prairie. TWI is working in partnership with the US Forest Service at Midewin, on a massive scale.

I visited the site for a couple of days to learn about the collection and sorting of seeds. Seasonal reseeding is a necessary part of wetland restoration. As we sorted seeds in the processing room, a unique vegetative smell filled the workspace each time we opened up a different bag of seeds. When out in the field, I just smelled ‘prairie’. But in each of these bags, I smelled something different: bluestem, swamp milkweed, false boneset, beard tongue and dropseed. I wanted to capture some of this experience in my artwork.

In my artwork Midewin Tallgrass Prairie, I included just a few of the restored habitats that knit together the wider ecosystem at this site. In the centre, I featured the Dolomite Prairie. It is a rare habitat and supports a unique blend of plants.

The braid at the bottom of the collar is in honour of ecologist and member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, Robin Wall Kimmerer, who wrote Braiding Sweetgrass. In this remarkable book, the author discusses the idea that by braiding together Native wisdom, ecology and science, we can work to sustainably and respectfully restore damaged habitats.

At the neckline of the collar is another reminder of the fluctuating water levels that are foundational to restoration work. I also included a suggestion of the huge concrete bunkers that used to dominate the Midewin site, which was once a US Army arsenal.

Smart wetlands

Across Illinois, TWI and their partners are demonstrating how small wetlands on farms can provide a solution to nutrient runoff while reducing costs over time for farmers. These ‘smart wetlands’ are meant to mimic the cleansing power of natural wetlands, offering an elegant and useful solution for the use of marginal ground on a field. Farmers appreciate the soil conservation and water quality improvements on their land, too.

When I visited these wetlands, I noticed that the plant diversity was very different at the entry point of the system. The water flowing in carries excess nitrogen and phosphorus, the run-off from the field. As the water flows through the system, these are taken up by wetland microbes and plants, resulting in a rich diversity of plants.

Cover cropping, another effective strategy for removing excess nutrients, is included in my artwork Smart Wetlands. I’ve embroidered a depiction of the crop rotation necessary to improve nutrient removal: corn, soy and winter rye. In this design, you can see the suggestion of row crop farming and how water is channelled from the field into the constructed wetland. The large triangular tangle of plants illustrates how the plant diversity increases as excess nitrogen and phosphorus is taken up by microbes and plants, as the water flows through the system.

Public engagement

After creating the artworks, I began the process of finding ways to put the project to work. The time had come to help others see the elegant and beautiful results of this restoration programme.

My work was shared in Oak Park Public Library in my hometown, and plans are afoot to show the work in various Midwest galleries and museums. Northwest Indiana Green Drinks, in partnership with Save the Dunes, hosted us for a presentation event, and I wrote an article for Illinois Science Council about TWI’s work in the industrial corridor of the Calumet region, which was published in February 2024. We also took the project to a Diversity Festival at Chicago Park District’s Big Marsh Park.

“Sending out proposals is an ongoing project that evolves as acceptances, and rejections, shape our outreach efforts.”

We are always looking for unique ways to share the project both inside and beyond gallery walls. This can bring added benefits. For example, at a recent exhibition, we were pleased to have several people sign up as volunteers for restoration work.

At a time when we are being challenged with the harsh realities of climate change, TWI’s work offers us a way forward, by using engineering prowess, a deep understanding of ecology and a willingness to partner with like-minded communities and conservation groups. And through this project, we are witnessing the creation of functional wetlands being clawed back from formerly degraded landscapes.

This ecology work has personal significance and deep meaning to every member of the TWI team. My work is a celebration of TWI’s success and I’m privileged to be able to help tell the story of wetland restoration. I can’t wait to see how these skilful and hopeful projects develop in the coming years.

Comments