UK textile artist and designer Maggie Scott first became known for her sumptuously crafted pieces of woven, knitted, felted and stitched wearable art. But, after 20 years in the industry, she received an Arts Council bursary that enabled her to put on a one-woman autobiographical exhibition, Negotiations – black in a white majority culture. And she noticed its impact on people of all races. She realised she could use her decades of well-honed textile techniques to exhibit and communicate the ideas, issues and stories she discovered, some of which rocked her world.

A new trajectory began. Today, Maggie makes large-scale works that express who she is: a black woman, a feminist, a daughter, a mother, an activist and a British textile artist.

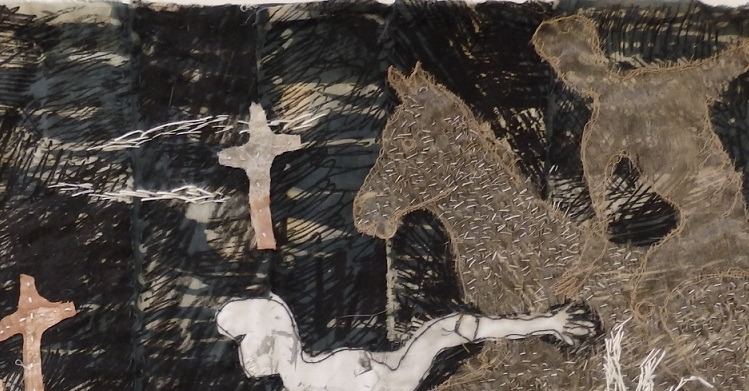

She specialises in hand-felting and hand-stitching, and incorporates photographs – often self-portraiture – printed onto silk chiffon and layered into the felt. Her artworks explore the politics regarding the disadvantages experienced by people of colour. Issues of fast fashion and the climate emergency also feature in her work.

Expressed through the tactility of merino wool, the finesse of silk chiffon and with strikingly large scale photographic portraits, you can’t fail to become engaged with the passion exuding from Maggie’s work.

Playful experimentation

TextileArtist.org: What initially attracted you to textiles as a medium? How was your imagination captured?

Maggie Scott: As a teenager, I loved to sew and make my clothes. At the time mini-skirts were in fashion, so it didn’t take much material to make a new skirt every week! I was about 14 years old.

A neighbour mentioned to my mother that there was a weekly sewing course at an art school not too far away. So off I went every Saturday morning to Farnham School of Art – not knowing that Farnham was actually one of the top centres for textiles and weaving at the time. I had a great time learning so much more than just sewing; we experimented and had fun with many different forms of textiles.

After that, I continued to focus on textiles, while on a foundation course at Farnham, and then for my BA degree at St Martin’s School of Art (now Central Saint Martins) in 1976.

It was an exciting time, and I can appreciate how lucky I was, not only to have access to a free education but also to be at a school that actively encourages its students to experiment, take risks and try things out.

For example, I was able to spend a whole term in the sculpture department, taking a break from fibre and fabric to explore other three-dimensional options. I was also able to spend a considerable amount of time working with plastic transparent tubes and fibre optics at Central School of Art (now Central Saint Martins), which at that time had a great weaving department. This was another environment where I was encouraged to play, experiment view myself as a designer and artist. Out of the seven of us who received first class honours that year, at least five went on to leading couture houses including Dior and St Laurent.

At that time I was very interested in machine knitting, and there was a very helpful and instructive tutor who did a lot of laying-in of fibres – a kind of intarsia, before intarsia was really known and automated. This was a time when people like Kaffe Fassett and Missoni and John Ashpool were revolutionising the industry with jacquard knits. When I left St Martin’s I was invited to join John Ashpool’s team in Italy as a knitwear designer working on ski wear and had a chance to try out some of my previous plastic weaving experiments!

What or who were your early influences and how has your life/upbringing influenced your work?

The earliest influence might be my art teacher at secondary school – I think his name was Mr Minter. When I bought some ‘counter culture’ magazines like OZ into class, he encouraged me to look more closely at the ways in which even cartoons were carefully crafted, and I think that made me understand how powerful art could be to change your perspective – art as activism.

But the biggest influence on my work was John Ashpool.

John, I believe, was a painter before he took over his father’s knitwear company, and his approach to the work remained very much that of a painter. We drew and played, we experimented – and in those days had an entire factory at our fingertips. I remember my first assignment was to produce the cuffs on a set of sweaters he had designed; I was assigned six or seven knitters, who were waiting for me to instruct them as to what size and shape. We experimented and at the end of the week, I presented perhaps 50 different versions of ribs for the cuff. John would then look at them, discuss them, play around with them, cut them up, change the colours. It was a fabulous, and very privileged, way to work. I think what captured my imagination then, and what has stayed with me, is the idea that you keep on going and don’t settle until it’s right.

Sometimes we’d make 100 and put them on the notice board, and John would look at each one, and perhaps choose a small section of one, perhaps a few inches of one of the samples. We would develop that section, go back and explore the shapes and colours he had found in those few inches. Other times, using what was then a revolutionary double-bedded jacquard machine, John would just play – changing colours in the middle, putting in another colour at random, just to see what it would do.

That was such a great lesson about how to approach the work: that you will know when it’s ‘done’ and when a piece is finished. I’m talking about working with colour, which has always been a key component in all my work. Of course, these days I have much less time to work on a project and, certainly, I’m not paid to spend so much time searching for the ultimate colour combination, but this process is still how I approach the work.

In terms of artists who have influenced and affected my work, I would have to put Yaacov Agam at the top of my list. He’s an Israeli artist who has created some extraordinary kinetic and optical installations, often using lenticular designs. I love his use of colour, geometric shapes and the movement. The way in which the colours move is something that I found hugely stimulating and important, and even now I still refer back, if not to his work, then to some of my own pieces that I made in the 80s.

My upbringing has influenced my work in a direct way, in as much as the textiles I’ve produced in the last decade focus on narratives and concerns that relate to the African Caribbean experience. Being black and female informs a lot of my work.

I was born in London to a working class family of recent immigrants, where nobody had any connection to art and craft, or college or university education. I was unique in going to art school and getting a bachelor’s degree.

Growing up in 50s and 60s Britain, the assumptions about what was possible were very prescribed by the times: I could be a nurse; I could be an athlete or a singer, but an artist or a designer, well, that never entered the conversation. So in a sense, my upbringing, the way in which I was raised in the UK, and the consequence of living in a white majority culture (and all the institutionalised racism that came along with that) did have an influence on my work, in that it probably delayed my claiming the title of artist, as I struggled for many years to believe that I was good enough and capable enough of being a professional artist.

What was your route to becoming an artist?

In a sense, the route in for me was due to the kindness of strangers, the kindness of the neighbour who told my mother I should go to a Saturday morning class at Farnham Art School!

But I think the route to becoming an artist, as opposed to a textile designer which I had been for about 20 years, was through an Arts Council bursary project called The Shape of Things.

I and seven other artists of colour and the global majority were selected and offered a bursary of £5,000 to create new work that would be showcased in one of four major venues: in my case, that was the New Walk Gallery in Leicester Museum and I had a large one-woman show in 2012.

I chose to produce some autobiographical work in order to talk about growing up in the UK in a white majority culture. The exhibition, Negotiations – black in a white majority culture, was well received and a huge turning point for me. I realised that I had things that I wanted to say and I could adapt the textile techniques that I had used successfully when making textiles to wear. But, crucially, it also showed me that the things I was interested in talking about resonated with other people – black and white. That was a huge learning curve. And it sort of ties in with the way I used to work with John Ashpool as a textile knitwear designer – where you keep going until it works, until it’s right, and trust that if it’s right and it works for you, it’s probably going to work for other people.

The freedom to produce what I wanted was a huge privilege. I had an enormous space in the museum, a crew and a team to help me put on a large exhibition. It included large felted textiles like Her hair grows which references the popular Tressy doll of the 1960s and the many ways my community transforms our hair – in particular the joy and pain of hair straightening. Early messages was a series on exploring identity and representation like Enid, which refers to Enid Blyton’s infamous children’s book The Three Golliwogs. It speaks of the images of black people that were fed to me and my generation by British popular culture.

The central piece of the show was a very large lenticular piece called Wedding day. Using a photograph of my mother and stepfather’s wedding day, printed onto silk, I chose to felt and stitch only things I could remember. I am intrigued by the gaze of the young me looking out, seemingly oblivious to the adults deep in conversation. But fifty years later, when I discovered that their wedding day coincided with a Keep Britain White rally just a few miles away in Trafalgar Square, I wondered more keenly what that conversation was about.

The exhibition also included Out of the shadows, a critique of the beautification industry and the seduction of skin lightening. As you enter the mock beauty salon, the shelves are full of real skin lightening products, as well as a fictitious new range called AM-NU. It was very exciting to do, very successful and also quite confronting.

The Negotiations exhibition was a game changer and a big turning point, because after that, I stopped completely making wearable textiles and concentrated on making pieces for exhibition.

Painting with fibre

Tell us about your process from conception to creation

Although most of my work takes the form of felted textiles and a similar palette, the way in which a work is conceived, and the decision to make a piece or a series, is quite different for each project.

However, the way in which I decide on a subject seems to be increasingly the same.

I found a lovely quote on Instagram by Petra Melville that I’ve used several times in talks and lectures. Its title is ’Are you an activist?’ and says: ’An activist is someone who cannot help but fight for something. That person is usually not motivated by a need for power, or money, or fame, but in fact driven slightly mad by some injustice, some cruelty, some unfairness – so much so that they are compelled by some internal moral engine to act to make it better.’

I’ll come across an issue, a story, an incident, and like everyone else will read about it. But somehow it will stay with me – often it will gnaw at me until I’m driven slightly mad by it, to the extent that I feel compelled to say something about it or do something about it.

It’s been an interesting way of working over the last few years; I found a way to link my activism and my art so they are interchangeable. Whether it’s joining the campaign to stop Zwarte Piet in the Netherlands or publicising the Polish Women’s Coat hanger protest, I no longer have to divide my time.

It’s not stopping art and then doing activism: they are now both one and the same.

So for example, my series Five times more began from something I heard a few years ago on BBC Radio 4’s Woman’s Hour. They said that black women were five times more likely to die in childbirth than white women. I was completely astounded and, in fact, I remember searching for the programme on BBC iPlayer, and listening again to make sure I’d heard it right! I started to look into it, and discovered there was a petition circulating demanding to know, why is this the case? I signed along with many other people. You may know that, once you have 100,000 signatures the UK government has to respond. So I got a reply from the government which to my astonishment confirmed those figures, along with several other bewildering statistics like: black mothers are 121% more likely to have a stillbirth than their white counterparts. It was extraordinary! And, yes, I did feel the need to talk about this.

I tend to work from photographs – for example, the pieces in Negotiations were based on family photographs – but more lately I have been buying licenses on stock images and using them as a base to develop a montage.

Tell us a bit about your chosen techniques and how you use them

Most of the time I use the nuno felting technique because it can be combined with my use of photographic images and collages.

Once I’m satisfied with the image, it’s printed on silk chiffon, and then wet felted. I enjoy the process, which sometimes feels like ‘painting with fibre’.

In one series I used the Union Jack flag as a background. My process allows me to decide how much of, for example, the red section of the flag is put in the foreground or the background – I control that by the amount of fibre and the colour of the fibre I use before I start rolling.

After it’s been felted, I spend quite a lot of time hand stitching, cleaning up fuzzy edges or adding an additional line, idea, or enhancing a colour. So it gives me, if you like, a third chance to alter the image. The first is on my computer playing with the photographic image. The second is felting it. And the third is stitching.

What currently inspires you?

That’s difficult to answer because all sorts of things will take my attention, but not necessarily as an inspiration. Some aspect of some work, or some imagery, will interest me, and I will make a note of it, or save it on my computer.

I am often inspired by an idea or subject. Something will take my attention that I’ll feel it’s important to talk about and explore. The inspiration comes in as I face the challenge of finding a way to express that idea. That comes from experimenting – from trying out different collages and from playing with different images.

I’m interested in a lot of African American artists, particularly textile artists like Bisa Butler, whose work has been shown at the Art Institute of Chicago. Whilst it’s not at all the technique that I use, I’m inspired by the boldness and her juxtaposition of colours and textures. And I think, more and more, that I want to start incorporating other fabrics into the felt.

Inspiring the viewer

Tell us about a piece of your work that holds particularly fond memories and why?

Like a lot of artists whose pieces take a long time, I become very connected to the artworks – they feel like your children, particularly when they are sold and leave the nest.

But a piece of work that comes to mind is Towards the End, a series that was part of my 2012 solo exhibition. It consisted of a series of four large portraits, which were actually portraits of my mother, taken about a month before she died. I used an overlay of a jigsaw puzzle, with each successive portrait having more displaced jigsaw pieces, so that by portrait number four, you can still see the image but it’s very disrupted and distorted by the missing jigsaw pieces.

I wanted to talk about the disproportionate number of black people in the mental health system and chose to use a portrait of my mother, taken about a month before she died. It turned out to be quite a powerful image that seemed to speak to many people.

For anybody that makes felt, you know that, once you’ve decided on the image and you’re in the middle of the process, your focus switches to the technique – the felting, the stitching, the mounting. In this case, I was preoccupied with the details in the portraits like making sure the eyes were felted correctly and the mouth was the right shape and not distorted through the rolling process. And I’d pick out areas of the jigsaw that needed to be sharper. It wasn’t until the four full portraits were up in the large exhibition space, and I could look at them from a distance, that I really got to see the power of the images. Because, of course, this was my mother, and it was depicting the very difficult period in her life before she died. I remember very clearly, being in the empty room the night before the exhibition opened and just standing and looking at it, and really being able to look with fresh eyes at this young woman who was just 49 when her life ended.

But although it was a difficult image for me, I have very fond memories of people’s responses to it. One woman, who had come to the UK in the 1950s, made a comment that always makes me smile. She spoke about how moved she was by my mother’s portraits, and I was so surprised to hear how joyful she thought they were. While I had put them up in an order from 1-4, with Number 1 being a complete portrait of a sad woman and Number 4 where the face couldn’t really be seen clearly, this particular woman had read the imagery from 4-1! She saw Number 4 as the confusion and distress of a woman arriving in 1950’s Britain from the Caribbean, then, as time went on, gradually understanding how things worked, settling in and making a life here. So, for her, Number 1 represented things improving and getting better.

It taught me how important it is to leave a space for the viewers to make their own interpretations.

How has your work developed since you began and how do you see it evolving in the future?

My work has developed in leaps and bounds rather than a smooth trajectory. In particular, my decision to stop making wearable textiles was a massive leap and an enormous change.

With each series that I complete, I’m learning more, developing more and adding more to my technique.

The nuno felts are quite methodical, while the abstracts – like the Omulolo series – have a life of their own. They continue to develop in a slightly different way which I enjoy. The abstracts take me back to design, where you’re preoccupied with shapes and colours and not worrying about, for example, how accurate is the nose, or whether the hair is in the right position. These kinds of things that are terribly important when you’re creating a narrative, a picture that has to tell a particular story.

I’m also exploring the possibilities of incorporating film and video and in a sense making the moving image an integral part of the textile.

After making the STOP video for Hastings Museum following George Floyd’s death, I began collecting short video clips where black people stated three things they wanted from their white allies. I have some rather interesting footage so I want to find a way that texturises the portraits. The ‘talking heads’ have a static textured overlay, taken from a very early photograph of a piece I made in the 90s, but I’d like to find a way to make them start talking!

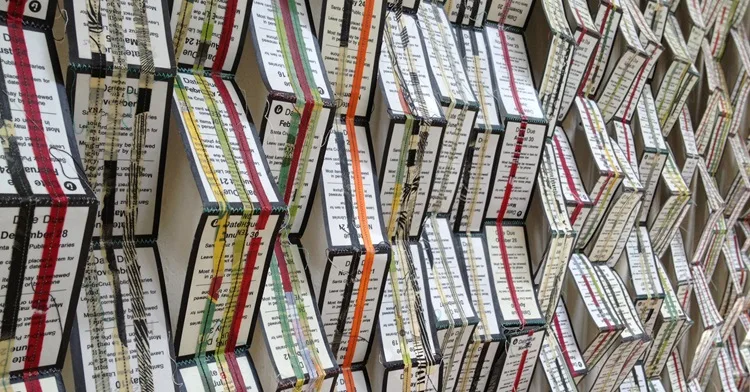

I would also like to develop some more installation work. I’ve been spending time on works related to the climate emergency, landfill sites and the impact that fast fashion in the global north has on the global south. I’ve made some two-dimensional pieces that illustrate the issue, but I’d like to develop a three-dimensional aspect to the work. I’m looking at how I can engage the viewer in such a way that they’re inspired to make a change or to take action. I’m hoping my work will evolve so that the textiles I produce are even more accessible or experiential.

11 comments

Eileen Sainsbury

I found the whole interview fascinating reading, and happy to think that the “kindness of strangers” helped on her development. I especially liked the comment about leaving space for the viewers to make their own interpretations.

Altogether an inspiring interview.

Anna

Thank you!

I gisp over Maggies work, brave hart and experience!

My biggest admiration!

Celia de Villiers

Love the mixed media techniques and Maggie Scott’s personal free and experimental approach as well as her forthright activism!

Carole Hallman

I am certainly inspired. The messaging combined with the excellent techniques. Glad to have been exposed to her work and process.

LEANORA MIMS

This work is very powerful! I am so glad she has a definition of activism that matches mine! Her work is so insightful!

Maggie Scott

Thanks so much Jana

Maggie Scott

Thanks Leonora…Always glad to know I’m not travelling alone!

Love to hear about your practice….

Jana Jopson

This interview is very compelling. Her energy comes right through: powerhouse. So glad to have read this and to know about her work in the world. Humanity needs her. Blessings.

Margaret Pratt 3

I love the way her ideas have developed over time and her reactions to small comments and happenings. She keeps pushing forward to make textiles say something to others. An inspiration to an 80+ Year old!

rose

as a child of the approximately same time as the artist, i can see things in my childhood that are the exact opposite and things that are uncannily similar, this disturbs and delights me in equal measures.

thank you for showing and explaining your installations .

Maggie scott

Thanks Rose… I’m glad some of my experiences resonated with you.