Imagine tackling your next textile art project as an athlete would. Setting daily, weekly and monthly goals. Tracking your progress in meeting those goals. Researching and analysing what does and does not work.

That’s exactly the challenge textile artist Marilyn Rathbone undertook when the Olympics came to London in 2012. She decided to literally “train” for a 100-metre dash in the most unexpected and creative way an artist could. And she learned as much about herself as she did her art.

This article showcases Marilyn’s creative process that combines research with technique. You’ll learn how she uses seemingly “ordinary” materials and just a handful of “simple” techniques to create extraordinary and compelling works of art.

You’ll also learn about her more recent exploration into illustrating mathematics. Both her stories of the process and understanding of the concepts will surprise and delight.

Marilyn graduated from Chichester University First Class BA Honors and was awarded the William Northam Prize for Academic Excellence. She has exhibited regularly with the 62 Group of Textile Artists since 2003. Her work has also been exhibited across the globe, including the United States and Australia. And she had a solo show in 2003 at the Otter Gallery, Chichester.

Finding inspiration in walks to school

TextileArtist.org: What initially attracted you to textiles as a medium? How was your imagination captured?

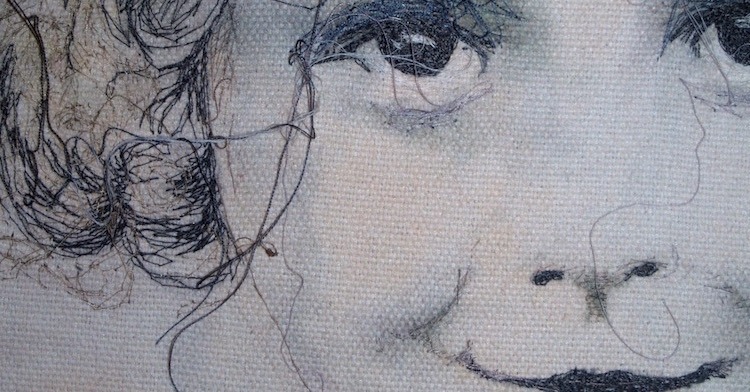

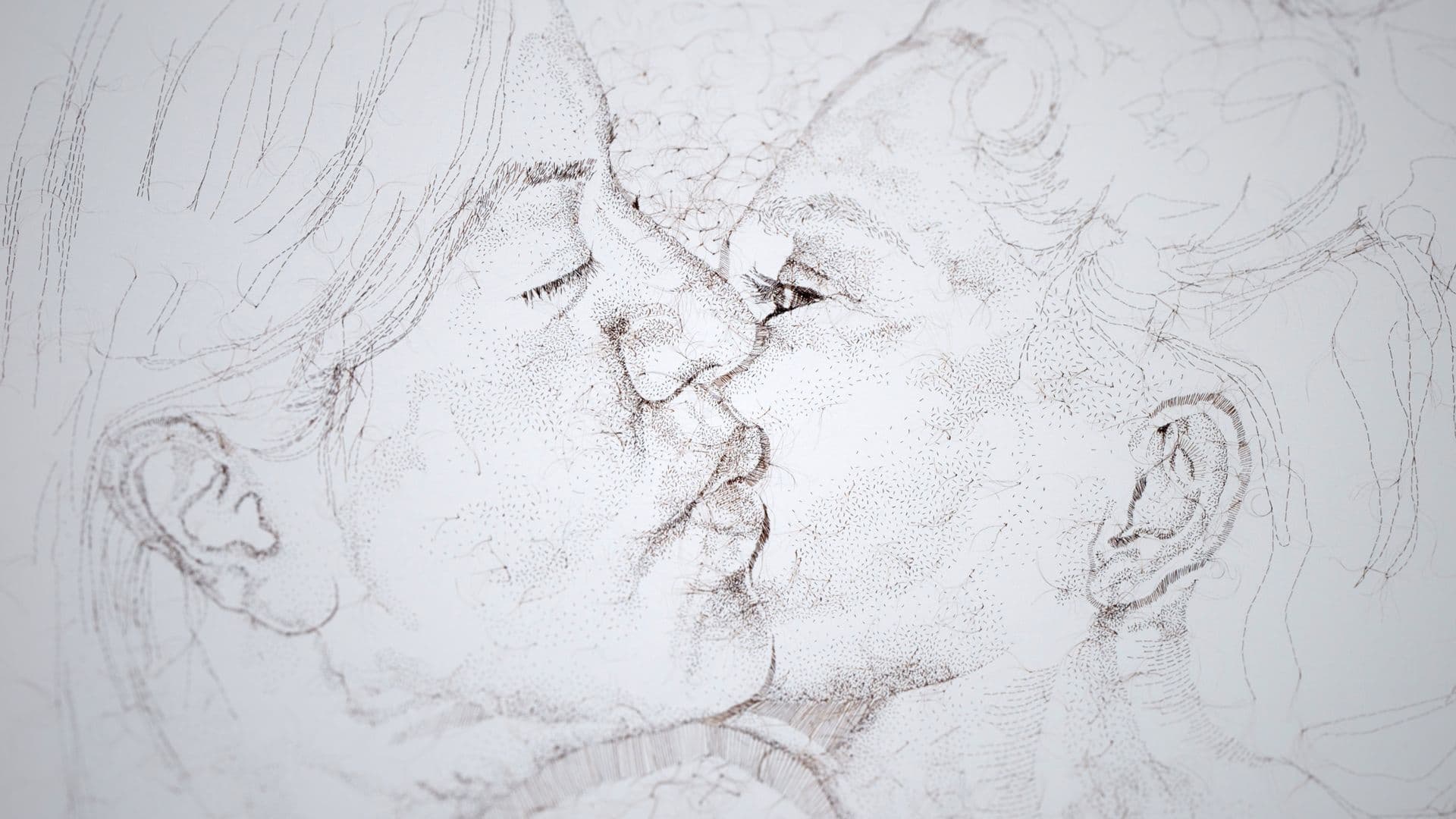

Marilyn Rathbone: I walked with my children to and from school along the same routes for eight years. Over and over I would see the same manhole covers, cracks in the pavements, petals, leaves and other materials. I wanted to somehow use the things I was seeing in my artwork.

Textile techniques were the logical way forward. And the end result was my “Pavement Works Collection” (1998-2003) featuring over 20 works, 2 of which were selected for Art Textiles 2.

I used natural elements to create the scenes. For example, I made small sheets of paper with petals and then rolled and folded some to form a paper “pile.” I also ground leaves to form coloured pavement “sands.”

I felted human hair and moulded it to form the grid patterns on manhole covers. And then I twisted paper and plaited, waxed and bound hair to form three-dimensional cracks.

I realised I loved working in this way of making, assembling and constructing.

What or who were your early influences and how has your life/upbringing influenced your work?

My mother sewed. She altered and repaired clothes, patched sheets, darned blankets and so on. And she still sews at age 89.

As a young girl, when my mother was making an item of clothing, she would let me play with some of the scrap material. I liked cutting it up with her pinking shears. The pieces would get smaller and smaller until they were too small to cut.

Occasionally I’d try to make a piece of clothing for one of my dolls. I don’t remember ever being successful, but I do remember having a go.

My grandmother also knitted and taught me that skill as well.

I think these early experiences made me comfortable with textile materials.

What was your route to becoming an artist?

My route to becoming an artist spanned many years of part-time study. I had always enjoyed and been good at art in school, but I did not continue on to an art college. I did, however, continue to draw and paint as a hobby, as well as knit and sew.

When my youngest child was six months old, I seized an opportunity to attend an evening art class once a week. It was part of a modular course that led to a Polytechnic Certificate in Art.

Five years later, I passed with an “A” and a distinction. I loved every minute of it and learnt so much that I didn’t want to stop. So I didn’t!

I applied to Chichester University and was accepted to their Fine Art Degree Course. This was also a part-time endeavour, but after seven years, I graduated in 2002 with a First Class BA Honours Degree and the William Northern Prize for Academic Excellence.

Training for Olympic textile results

Tell us about your process from conception to creation

On the whole, my work is led by ideas in a cyclical way. Ideas for new work often occur while I’m working on a piece. And then when I start working on that new idea, yet more ideas are sparked for the next work after that, and so on.

My work entitled “100 Metres Dash” (2011-2012) is a good example. It was sparked by a quote from Andrew Hamilton, a sports magazine editor: “How many truly remarkable things have you done in your life? If the answer is not many, or even none, then maybe it’s time to run a marathon.”

I’m not athletic, but with the build-up to the London Olympics underway, I wanted to feel I was part of it all. And then I had an idea: my marathon challenge could be to hand weave a 100-metre-long braid.

Thoughts started flooding in after that. I could use the Olympic symbol’s colours. I could weave a literal 100-yard dash across the entire length of the braid.

I then started gathering as much information around those ideas as possible. I researched the topic, analysed the findings, and thought about possible techniques to try. I also worked on the practicalities. Will I be able to do this? And if so, how?

I realized all the research and effort going into creating my art correlated with the way athletes train for an event. Making a 100-metre braid by hand would be an enormous task, so I’d have to be very disciplined and “train” to complete it.

To that end, since athletes use personal training programs and progress charts to help meet their goals, I, too, decided to devise a training program.

After setting my 100-metre braid goal for July 2012, exhibition, I completed some “trials” to see how long the braiding process would take and the length of thread I would need. It was very slow work: 10 centimetres an hour. Knowing I wanted to complete the piece a few months before the exhibition deadline, I calculated I would need to work 3 ½ hours a day, 6 days a week, for 48 weeks.

I then broke the 48 weeks into 6 phases, each with its own completion target. The first four phases would feature the greatest amount of work—the “training.” The fifth phase would be the “final” 50 strides, and the sixth phase would be “recovery.”

I used a Progress Chart throughout the process noting issues and solutions, including where I fell behind schedule, where I lost focus, etc. I actually compiled those notes and progress bulletins into a booklet that can be viewed here.

Ultimately I wasn’t successful meeting my 48-week goal. It took me a year and a day to complete the work. But my use of an athlete’s regimen definitely contributed to the piece. I couldn’t have done it without those goals and progress charts. But I also discovered I wouldn’t want to work in such a regimented way again!

While I usually don’t start making a piece until I feel sufficiently confident my idea is both sound and do-able, not everything is planned. Instead, I identify and solve problems along the way. And as a piece progresses, it seems to develop its own logic and takes control of its own destination.

The metre markers in the Dash are a good example. They came about through necessity. The longer the braid grew, the more awkward it was to measure. So after watching athletes on TV place markers on the track, I decided I would use markers too.

Chance also plays a role in creating. I noticed the small reels of cotton thread I bought held 100 metres of thread. So, I had the idea to use a large cotton reel in the piece. I ordered one from eBay, but it arrived damaged, and I had to repair it.

I then had to paint the reel to hide the repair, and I think the ivorine colour I chose ended up looking better than the original unpainted wood. Had the reel not been broken, I probably wouldn’t have thought to paint it.

Lastly, I believe the making process or craft aspect of textiles is very important and reflects what athletes sometimes describe as “being in the zone.” When I am making, I stop analysing what I’m doing because I’m absorbed in the moment. Working in this way inevitably leads to some surprising outcomes. And for me, those outcomes often surpass anything I might have thought of when I had my first idea.

Tell us a bit about your chosen techniques and how you use them

When I joined the 62 Group of Textile Artists in 2002, curators were very keen to have themed 62 Group exhibitions. So it came as rather a jolt to the system that although I had ideas for new Pavement pieces, I would have to make something un-pavement related.

But it was the right time to move on. My children had grown up, and I wasn’t walking those routes any more.

I liked how my “Pavement Works” championed the overlooked or ordinary, and I wanted my new work to continue to do so.

So I decided to focus on some of the more “humble” textile techniques I’d used in my “Pavement Works.” My piece “Water” (1998) is such an example, in which I used inkle weaving (box straps), braid making (lid stays) and button making.

I also knew my use of the pavement as a linking element in my work had allowed me to use whatever medium or technique I chose. I wanted to continue to have a linking element in my new work too, so I flipped things around.

Up until then, I had been working with a limited subject matter but an unrestricted choice of techniques. Now I would work with an unrestricted choice of subject matter and a limited choice of techniques. This way the techniques would link the work and provide me with an opportunity to experiment with and learn more about braiding, cording and button making.

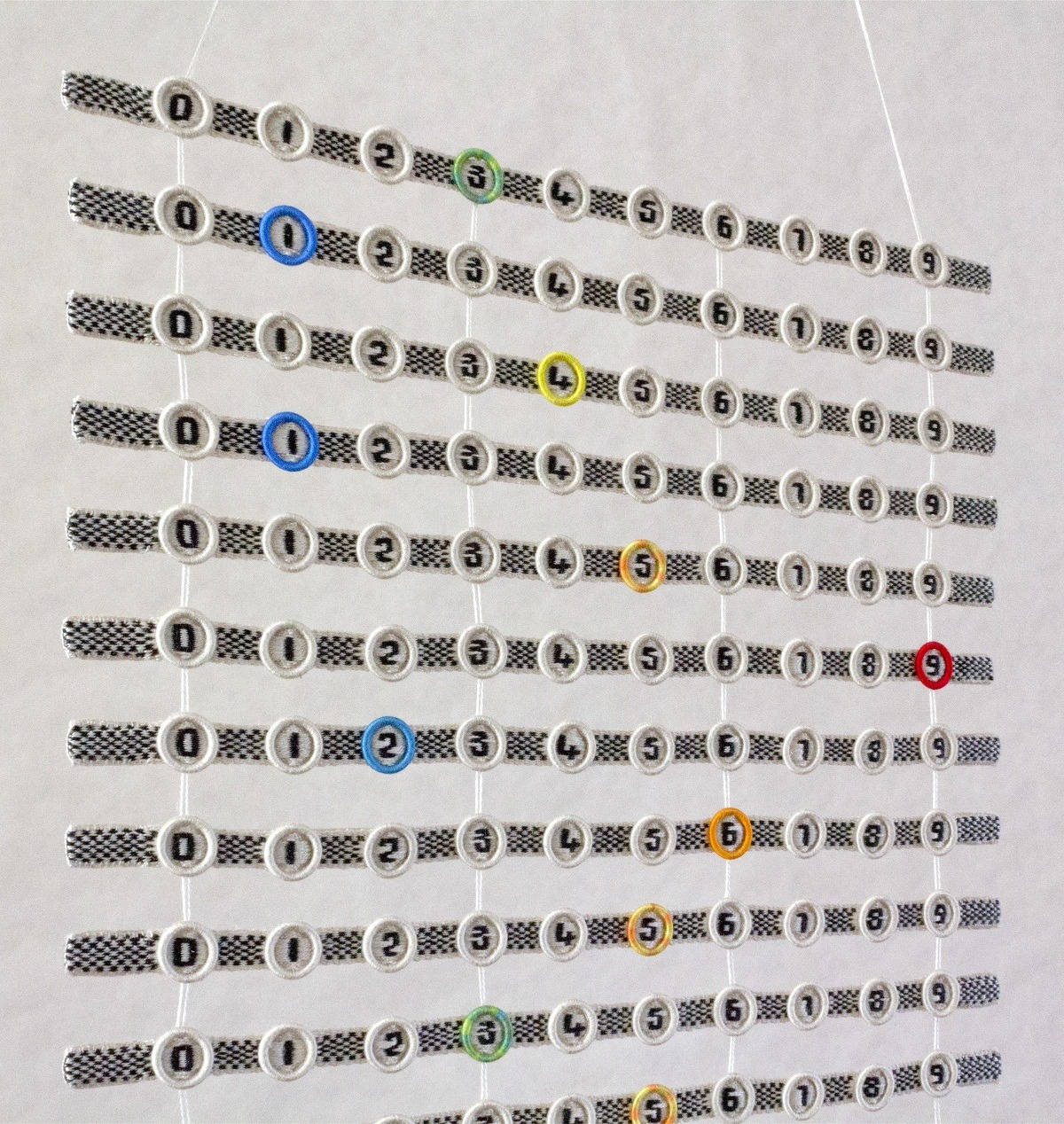

As my knowledge increased, I was able to make more complex braids and buttons. I now use different braiding techniques for different purposes. Inkle weaving enables me to use words and numbers in my work. A hand-held Lucet enables me to produce long continuous lengths of braid. And Kumihimo (loom-based Japanese braiding) allows me to produce many different colour patterns. Button making also allows me to produce discs of colour.

What currently inspires you?

I’ve become fascinated by mathematics, and number sequences in particular, which was largely kick-started by braid-making.

I made several pieces inspired by the snake collection at the Cambridge Museum of Zoology (2005-07). I had to work out specific braiding sequences to recreate the characteristic colour patterns of vipers and pit vipers.

Working on those colour sequences then sparked the idea for my next piece “6 Degrees of Separation” (2008-09) that featured a set of six number sequences.

Number sequences are infinite, so it was up to me to decide how many of each sequence to braid. I chose the number 60 because it is a number of many parts. It has been dubbed “the ace of divisibility,” so 60 has become my go-to number.

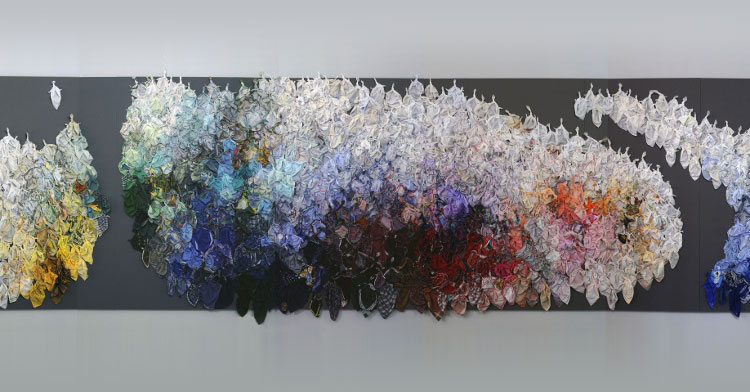

The “Bauhaus Braids” (2015), for example, shows the first 60 numbers of each sequence. This set of three braids also combines Kandinsky’s colour-shape theory with numbers. Triangular numbers are yellow, “sharp” and edgy. Square numbers are red, “earthbound” and balanced. And circular numbers are blue, “spiritual” and the colour of the heavens.

Other times, though, it isn’t up to me to make the decision, as with my “Pi in the Sky” (2016) piece. It was inspired by the fact that to calculate the circumference of the observable universe to within an accuracy of an atom, you need only the first 39 digits of Pi.

Knowing Pi has been calculated to trillions of digits and memorised to thousands, just the first 39 are needed? Really?

I had to celebrate that mind-boggling fact.

Who knew “maths” could be stitched?

Tell us about a piece of your work that holds particularly fond memories and why?

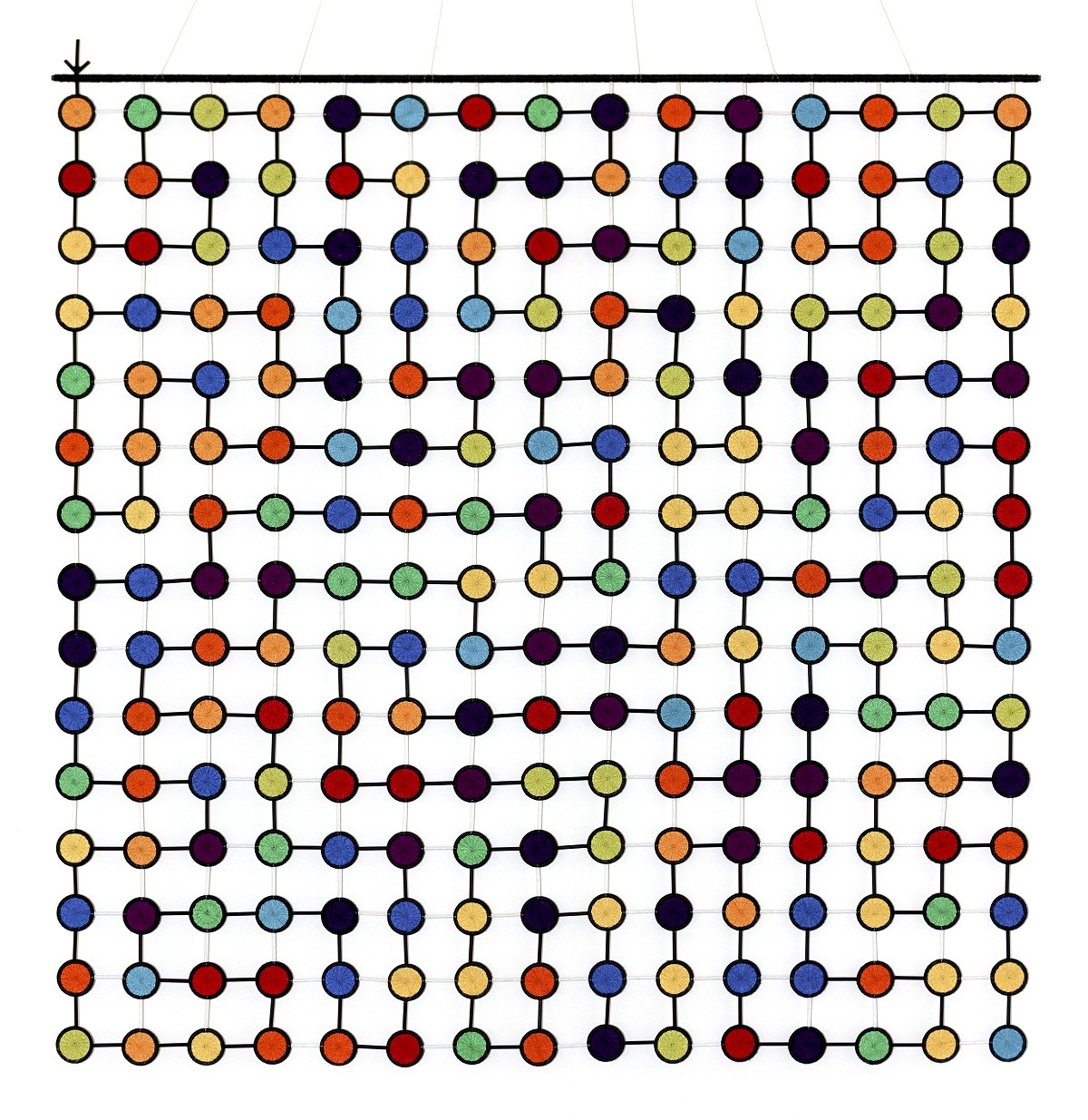

I’m rather fond of my most recent artwork, “Self-Avoiding Walk” (2017-18). When making a piece of artwork, you must make decisions about structure, colour, and line. I’m often asked how I decide these things. It got me thinking: could I make an artwork without having to make any of these decisions?

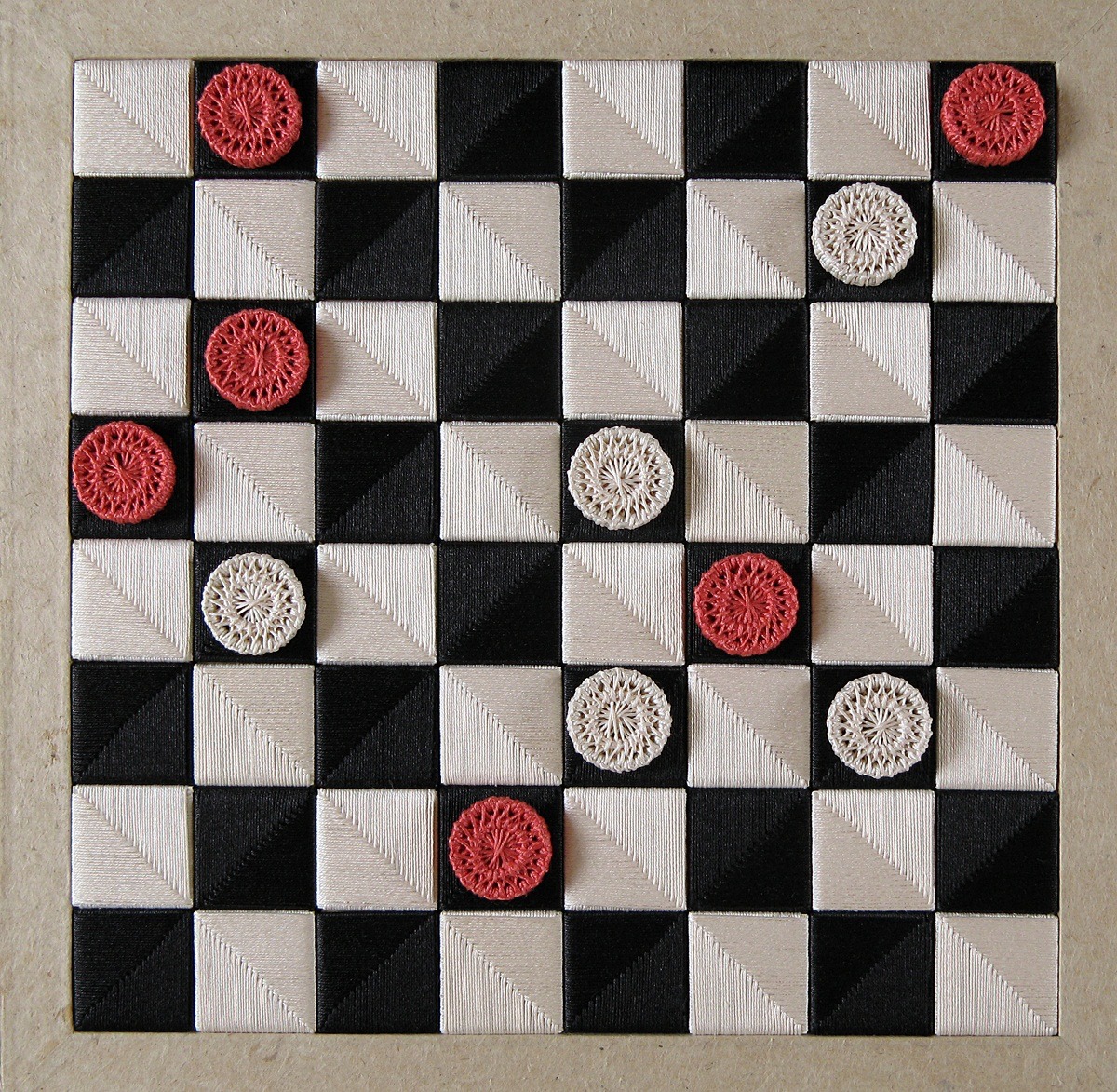

“Equivalent IX” (2010-11) had gone part way in that regard. The piece consists of nine sets of nine counters, each set a different colour. There is no specific way in which to lay out the counters. They can instead be arranged in different configurations thereby transferring the decision about the structure of the piece to the curator or owner. Explore “Equivalent IX” more with a video Marilyn created here.

Still, I didn’t want to simply re-use this multi-choice approach. Could there be another way?

Having Googled the phrase “avoiding decisions,” imagine my glee when it came up with a mathematical diagram of a self-avoiding walk. For a self-avoiding artwork, what better structure could there be?

In mathematics, a self-avoiding walk is a sequence of moves that takes you through a lattice without visiting any point more than once.

The mathematical diagram was in black and white, which raised the next question: what colours to use and in what order?

I managed to side-step that decision by letting Pi’s random numerical sequence lead the way along the walk. Each digit was represented by a specific colour from 10 evenly spaced colours around the colour wheel and tonal gradations from light to dark.

For the decision about line, I must thank fashion designer Julien MacDonald for his enthusiasm for bugle beads. They were the final piece of the puzzle.

“Self-Avoiding Walk” is a feel-good piece. The concept behind it is playful. It was fun weaving the colourful Dorset buttons, and equally fun seeing the random colour combinations emerge during its construction.

But the icing on the cake was seeing first-hand the public’s reaction to it over the three weekends of my local art trail. Smiles all around.

How has your work developed since you began and how do you see it evolving in the future?

Mathematics has become a linking element in my work, so I could return to using whatever medium or technique I choose. But that’s not to say I will do so.

I still have ideas I’m mulling over for new work using braid and button making techniques. There is so much more for me to learn about these seemingly humble practices. I’ve barely scraped the surface, but it feels liberating that I have given myself permission to do so if I wish.

What advice would you give to an aspiring textile artist?

Stoke the fire, do the research, and then allow the work to evolve.

For more information visit www.axisweb.org/artist/marilynrathbone

Let us know what you think about Marilyn’s “training” approach for tackling complex works of art by sharing your comments below. Do you think it might work for you?

10 comments

Mary Pescod

I have one of those wooden things you did your braid on but I have never known how to use it or what it is called. Can you tell me and direct me to a you tube or something to show me how to use it, please? Thanks in anticipation.

Marilyn

The wooden implement is called a Lucet. I bought my first one from The Braid Society Stand, at a Knitting & Stitching Show, quite a few years ago. It came with basic instructions and it really is a very quick and easy technique to pick up. I believe there are lots of You Tube videos out there but, as I haven’t looked at any myself, I’m not in a position to make any recommendations. I learnt the other variations of technique from a couple of books: Lucet Braiding, Variations on a Renaissance Cord by Elaine Fuller, Lacis Publications, 1998 ISBN 1-891656-06-6; and Advanced Luceting, the Ziggy-Stitch Technique by Z Rytka, 1999, ISBN 0-9536478-0-3.

I hope this helps to get you started and that you go on to enjoy many years of Lucet cord making.

Marianne

I am amazed. All your works are fantastic. Congratulation!

You are a highly gifted person – thank you very much that display for us!

Have a nice week

Marianne

Marilyn Rathbone

Thank you everyone for your comments – glad you liked the article.

Kevin Penney

Fantastic article and I love your work – thanks for letting me know about it.

Paul and Jan Doran

We had little awareness of the art form and were pleased to hear of an Open Day where Marilyn was exhibiting – it was a mind-blowing experience, and now having seen and read this article we are reminded of how talented she is.

What comes across to us as non- artists is that whatever the endeavour there is no substitute for planning, programming and dedication , yet Marilyn humbly says she `allows the work evolve`.

Michael Crompton

Having been interested and fascinated by your concepts and ideas and the way your processes are integrated I was pleasantly surprised to hear that you were at Bishop Otter College Chichester.

I was there from 1961 – 1964 and the experience set me off on my pathway as a textile artist. The whole environment with so many original works of art displayed around the campus was stimulating.Particularly when the Jean Lucat tapestry was unwrapped. My career has been in image tapestry with a real emphasis on the design process. You can see something of my work on my latest website.

http://www.michael-crompton.co.uk

So sad to hear of the closure of the “Otter Gallery”

I look forward to seeing more of your work as it develops.

Michael Crompton

Linda Carswell

This was an amazing mammoth exercise and must have required a lot of discipline. I think a regular ‘work ethic’ is good but I could not work so formally as this.

Gwyneira M. Wood.

That is the most mind breaking concept I have ever experienced. It certainly makes one realise that ideas, planning, practise and deeper thought should always apply before spending time on producing any piece of art work and particularly textile art. GMW.

Jan Scott

I remember you very well when we were at Chi Uni together. Your attention to detail was impressive then even more so now. Great work, great article, thanks,

Janet Scott