“The sense of smell is the hair trigger of memory.”

Mary Stewart, British novelist

Research has proven that the nose knows and remembers. The slightest hint of a familiar fragrance can take us back in time and space, and, according to Pallavi Padukone, that phenomenon is good for both wellness and wellbeing. After successfully using aromatherapy to help manage the stress of the pandemic, Pallavi decided to turn the fragrance industry on its head by creating ‘olfactory art’.

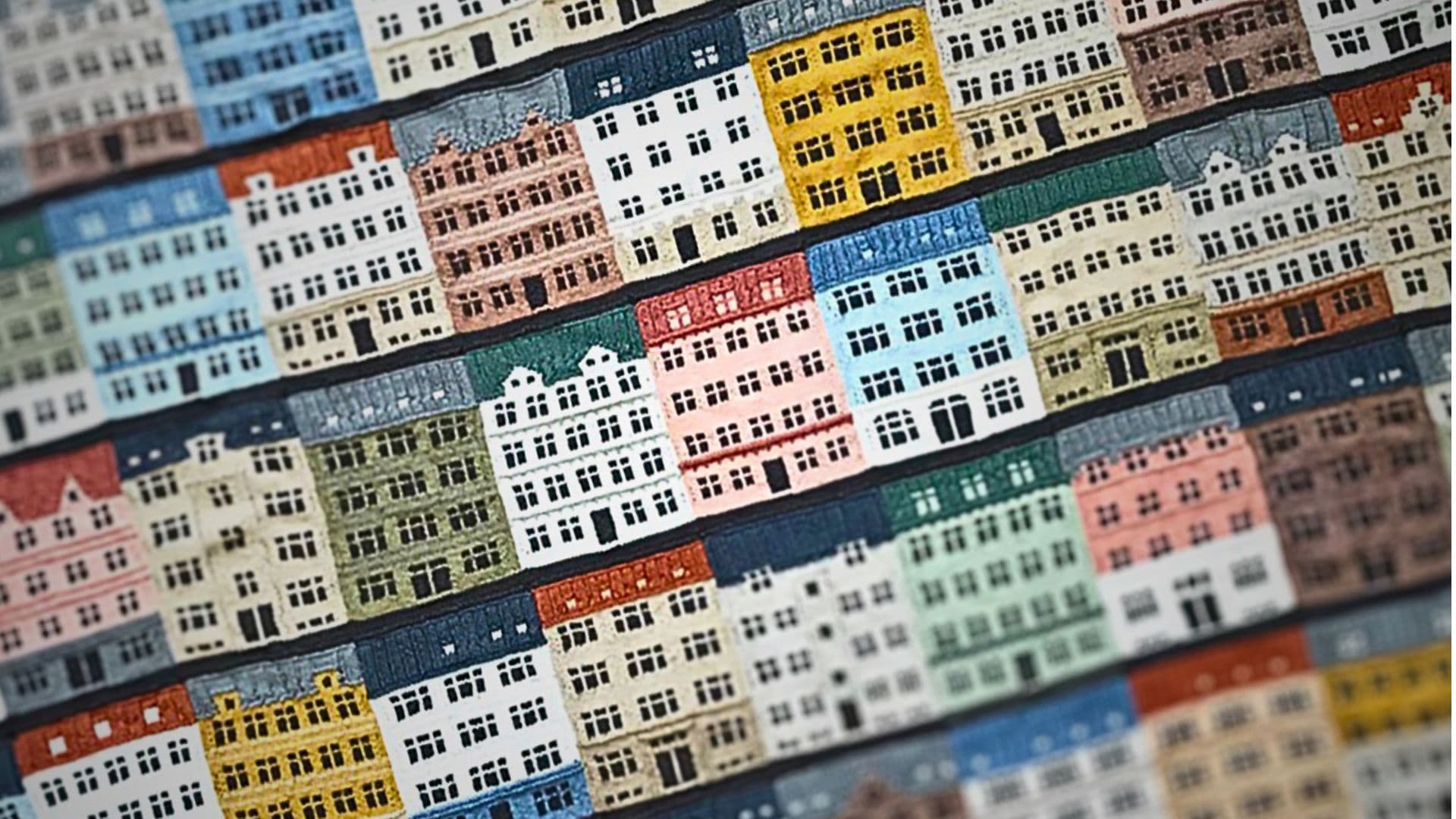

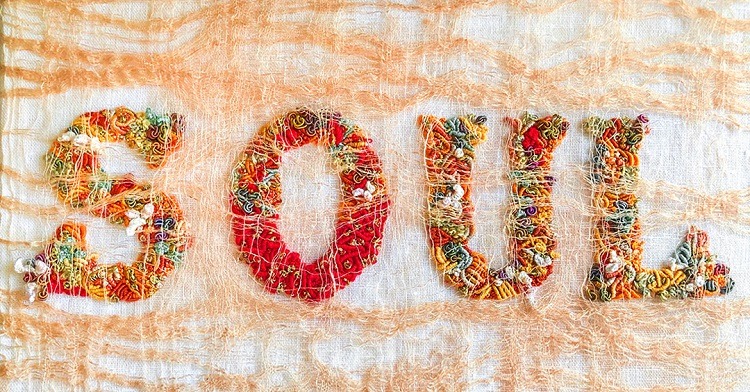

Pallavi’s tapestries and embroideries are literally fragrant. She weaves and stitches with yarns and threads soaked in naturally derived scents like jasmine, rose, and sandalwood. She also dyes her materials with Indian herbs and spices including safflower, chilli and turmeric. Pattern, colour, texture and scent combine to recreate memories of Pallavi’s childhood in southern India.

Pallavi continues to finetune her techniques and expand her library of scents, but she has generously taken a moment to offer us an insight into her current process and techniques.

We wish we could offer you a scratch-and-sniff option while reading about her work, but we promise you’ll still be delighted to learn about her inventive art that tantalises both the nose and the eye.

Pallavi Padukone: I was exposed to different forms of art from an early age. My mother is a graphic designer and used to work at a gallery in Bangalore, India. Growing up, I’d often visit her at work. I was also enrolled in a weekend art class led by one of the artists.

One of my first experiences involving textiles was at a school tie-dye workshop. It was the first time I’d played around with dyeing fabrics.

I also have fond memories of my grandmother teaching me how to embroider. I sat with her in the evenings, and she would patiently show me different embroidery stitches and knots. She also made me a little guide to help me practise.

I studied textile design during my undergraduate education in India. I decided to specialise in textiles because working with my hands came naturally to me. An exchange semester for a fibre art course in Gothenburg, Sweden, really opened my eyes to how complex textiles can be.

I learnt how to view fibres and fabrics with a conceptual lens. I fell in love with using textiles as an art medium after experimenting with different techniques and meeting many interesting people in the field.

I later studied at the Parsons School of Design, New York, where I focused on integrating scent and textiles, using fragrance as a form of embellishment.

Connecting to culture & place

All the materials I use in my work are chosen for their sensorial qualities. There’s a connection to landscape, place and time that is woven into each work’s backstory.

I integrate hand-spun recycled sari silk mixed with scent-coated cotton for my weaves and embroider on silk organza. I retain the existing jewelled colours the silks are sourced in. I am drawn to the way the sheer fabrics interact with light to visually evoke the ephemeral experience of fragrance.

My work is guided by culture and craft, and I believe in the philosophy of respecting the artisanal, the sustainable and the slow.

“I often use nature as my muse for colour, patterns, and materials.”

Pallavi Padukone, Olfactory artist

My Indian heritage also constantly informs my textile art. Textiles are so deeply rooted in India’s history – their richness and craft inform both my approach and design sensibilities for patterns, motifs, techniques and colour.

My use of colour comes intuitively from sights, my surrounding landscape and imagined memories. I can be inspired by something as simple as certain shades of flowers at a market or an interesting colour-blocked sari I spy someone wearing.

Olfactory art

The idea of using fragrance for its therapeutic qualities and its connection to nostalgia and memory resonates with me.

My initial source of inspiration was the calming effect a small pouch of lavender provided while cooped up in my apartment during the 2020 lockdown.That prompted me to explore scents for wellness and how they could be visually expressed through colour, pattern and texture.

As part of my research, I conducted surveys to record the relationship people have with fragrance and their link to memory, emotion, visual imagery, colour and texture.

I then considered how fragrant yarn itself could open doors to possibilities through textile techniques. Through trial and error, I developed a natural coating for yarn that captured scents.

The Reminiscent collection is inspired by the scents and colours of memories and nostalgia connected to my home in Bangalore. There are a total of 14 wall hangings, tapestries and room dividers that stimulate the senses beyond sight with a feeling of familiarity.

The collection keeps evolving as I keep adding to my library of scents. It’s been a fascinating learning process. Reminiscent seeks to reinterpret the fragrance industry by tapping into scent’s ability to serve as powerful catalysts for triggering memories, especially feelings of calm and comfort.

“It’s a way to use textiles as aromatherapy to condense time and distance, as well as create an immersive experience to reconnect with nature, nostalgia, home and identity.”

Pallavi Padukone, Olfactory artist

Creating scented yarns

The six scents that I started my collection with were jasmine, citronella, vetiver, rose, sandalwood and clove. I’ve added hibiscus and ‘spice rack’, which is a combination of cardamom, clove and turmeric. All these fragrances bring me a sense of comfort, and I associate them with the smell of home and my childhood.

“My memories include the scent of sandalwood talcum powder on my grandmother’s dressing table”

Pallavi Padukone, Olfactory artist

Jasmine buds in our terrace garden, rose garlands in the flower market, citronella mosquito repellent during summer months, and the petrichor-like fragrance of the vetiver root that’s reminiscent of the monsoons.

The scented yarn coating I developed is wax based. It’s combined with tree resin and pure essential oils, and then coloured with natural dyes and earth pigments. The mixture is warmed, and the yarns are individually dipped, coated and dried.

The resin helps to harden the mixture. Yarns are then put into sealed bags for them to dry and lock in the scent ready for use in my tapestries. It takes about 48 hours for them to dry and harden slightly before I use them.

When yarns are heated at the right temperature, the combination of wax and resin make them quite malleable and versatile for weaving and embroidery. But they do have limitations.

Since yarns are individually dipped, they’re created in small quantities and not as a single continuous long length of yarn. That equates to a more time-consuming process, but small batches prevent waste because I can estimate how much coated yarn will be needed for each colour and scent.

I also make my own scented beads using the same pigmented and scented mixture used for my yarn, by casting the mixture into customised 3D printed moulds that I designed. I use the beads to embellish my work. Vetiver III is an example where I integrated the beads into the warp of the tapestry.

Fading fragrance

A collection tends to remain fragrant anywhere up to three months, depending on exposure to heat and light. But that impermanence is a reminder of its completely natural state and that it absorbs new smells, just as dyes tend to alter over time.

“It’s a fact that scent is temporary, and because I work with completely natural materials, it will fade over time.”

Pallavi Padukone, Olfactory artist

I keep a record of swatches as a test of the material’s durability and how long both scent and colour last when exposed to heat and light. The yarn and beads can be reactivated by adding another coating of scented oils, but the fragrance still tends to fade. So, part of my ongoing exploration is innovating new ways to replenish fragrances.

I also plan to continue to expand my library of scents to capture other places and memories dear to me.

A natural dye palette

I experiment with different combinations of dye matter to build my palettes. I mix various natural dyes in different proportions with a base of wax and natural resin.

The shades of brown come from walnut, natural earth clays and cutch extract from acacia catechu wood. Ocher pigments, reds and pinks are from madder root, hibiscus and beetroot. The orange colours come from safflower and chilli, yellows from turmeric, and blues and greens from a combination of indigo and turmeric.

“Each work’s dye palette features colours I associate with the memories I hold for each of my fragrances.”

Pallavi Padukone, Olfactory artist

With jasmine, I associate its sweet scent with delicate soft hues of pinks, creams and pastel green. But sandalwood is more a musky, powdery and creamy wood scent, so for this I use more earthy browns and deep wine reds.

Experimental weaving

My first interaction with weaving and using a handloom was during my undergraduate education. I find the repetitive motion of weaving so meditative. I think I truly fell in love with the process of weaving after travelling to Patan, a city in Gujarat, India.

There, I met master weavers who specialised in the complex double ikat weaving technique called ‘patola’ where the warp and weft are resist tie-dyed. I was absolutely mesmerised by its complexity and seeing each step in the process come together to weave the patterns.

I use a handloom, and I’ve more recently begun using tapestry looms or making my own frame looms.

I call myself an ‘experimental weaver’, as I love weaving with different materials and moving beyond using only yarn. Vetiver roots are a favourite, but they definitely pose challenges that lead to a great learning process.

The roots themselves can be quite brittle, but I enjoy leaning into its limitations. I’m exploring ways to combine machine embroidery with wet felting to help tame the material in ways that keep its natural wildness.

I still have so much to learn and discover, and I primarily teach myself by reading and watching online tutorials for embroidery and weaving. I’m also grateful to live in a city that has access to great libraries, museums, art galleries, talks and seminars that provide great opportunities for inspiration and meeting others in the field.

Vetiver embroidery

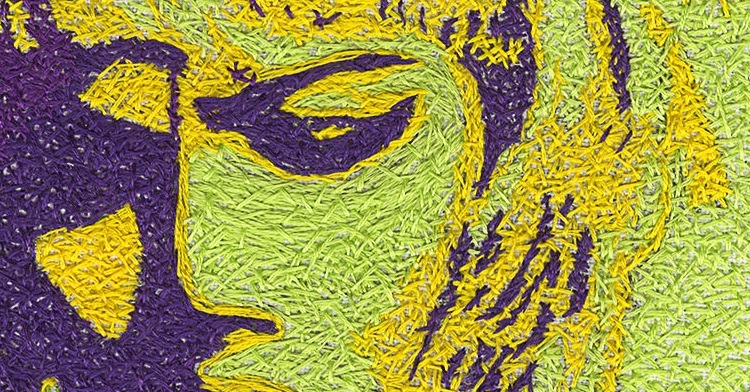

In addition to weaving, I also wet felt and embroider on top of the fragrant vetiver (khus) grass root. It releases the most divine petrichor-like scent (like the earthy smell after rain) when activated with water.

I have tried to use vetiver in my woven pieces as well as using it as a dye, but it produces a very light colour that fades quickly.

For my embroidered works, I carefully choose yarns and threads for each piece. I like the simplicity of the running stitch. I also use quite a bit of free-motion machine embroidery, as well as hand smocking techniques on silk organza.

I tend to use cotton threads for embroidery, and polyester or nylon threads for my vetiver root artworks that involve interaction with water.

Tree of life

For my undergraduate final thesis project, I worked on a sculptural hand-woven installation called The Kalpavriksha. I’d say that project was a key turning point in my textile art trajectory.

The work was inspired by South India’s ‘Tree of Life’, which is a coconut palm eulogised as the mythological tree that grants all life’s necessities. Every part of the tree, from its leaves to its roots, can be used for food, drink, shelter, medicinal purposes and more. In Indian tradition, a tree is not just an object of nature. It’s treated as a shrine and source of bounty.

I collaborated with handloom sari weavers and cane-work artisans from Bangalore. The sculpture symbolises the dissected coconut and represents how every layer of the tree and fruit is valued. The spreading roots made from braided coir (coconut fibre) represent its ever-evolving nature.

The coconut fibre was donated by the coir cluster of Gandhi Smaraka Grama Seva Kendram (Alleppey, Kerala), a non-profit organisation that promotes sustainable agricultural development.

Six fabric information panels accompany the exhibit, with details about why the coconut palm is revered and how it travelled to the Malabar region. The last panel features a folktale from Kerala about its origin. The installation was part of a travelling exhibit funded by the Dutch Consul General and Embassy in New Delhi.

“I find it challenging to put my work out there. Many times, I don’t feel that an artwork is ready, or I overthink some of my pieces.”

Pallavi Padukone, Olfactory artist

Navigating social media

There are times I have ideas in mind, but I need access to more resources or collaboration with an expert to bring them to life. Networking and self-education can provide good advice and guidance, but sometimes I can’t find the information I need to move forward with a project. It’s all a slow learning process.

At other times, just mustering inspiration to make something can be a challenge. When that happens, I’ll visit museums and art shows or travel. Trips back to India to visit my family and source materials always fuels my creativity.

I have mixed feelings when it comes to using social media. I do realise it’s become the standard way to showcase and promote your work as an artist. More people ask for an Instagram handle versus a website or email.

But I do struggle to maintain consistency when posting. Quite often I don’t post because I feel intimidated sharing my work, or I question if a work is ready to be posted.

It’s a challenge I need to overcome. I do use Instagram to follow other artists and designers, and being a textile designer working in the area of home interiors, I use it to stay informed about new developments and interesting projects in the industry.

2 comments

Marykay Hymes

Fascinated by this work! I would love to find how to capture the deep purples and fragrance of irises since they remind me so much of late spring.

Theresa Watson

I once added perfune oils to plaster that had wire, threads, stitches, and real leaves. Inspired by Shakespeare’s sonnets. A winter scene, panel. I hung the panel from paintrd wood with wire. Almost like an ice palace when finished.

Your work is lovely and delicate.