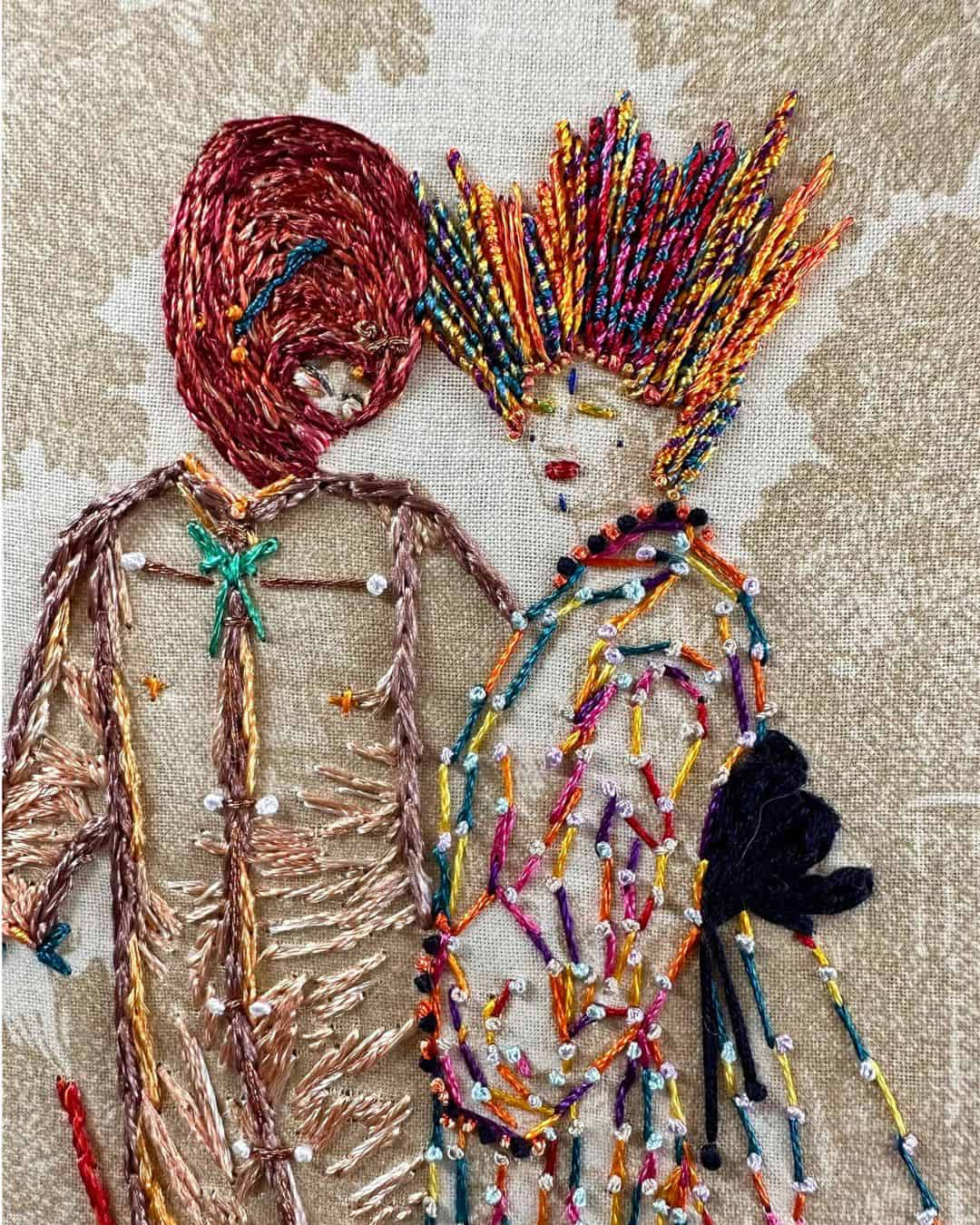

Viewed from afar, Richard Saja’s bucolic pastoral scenes seem peaceful and tame. But upon closer inspection, you’ll find plenty of mischief and mayhem.

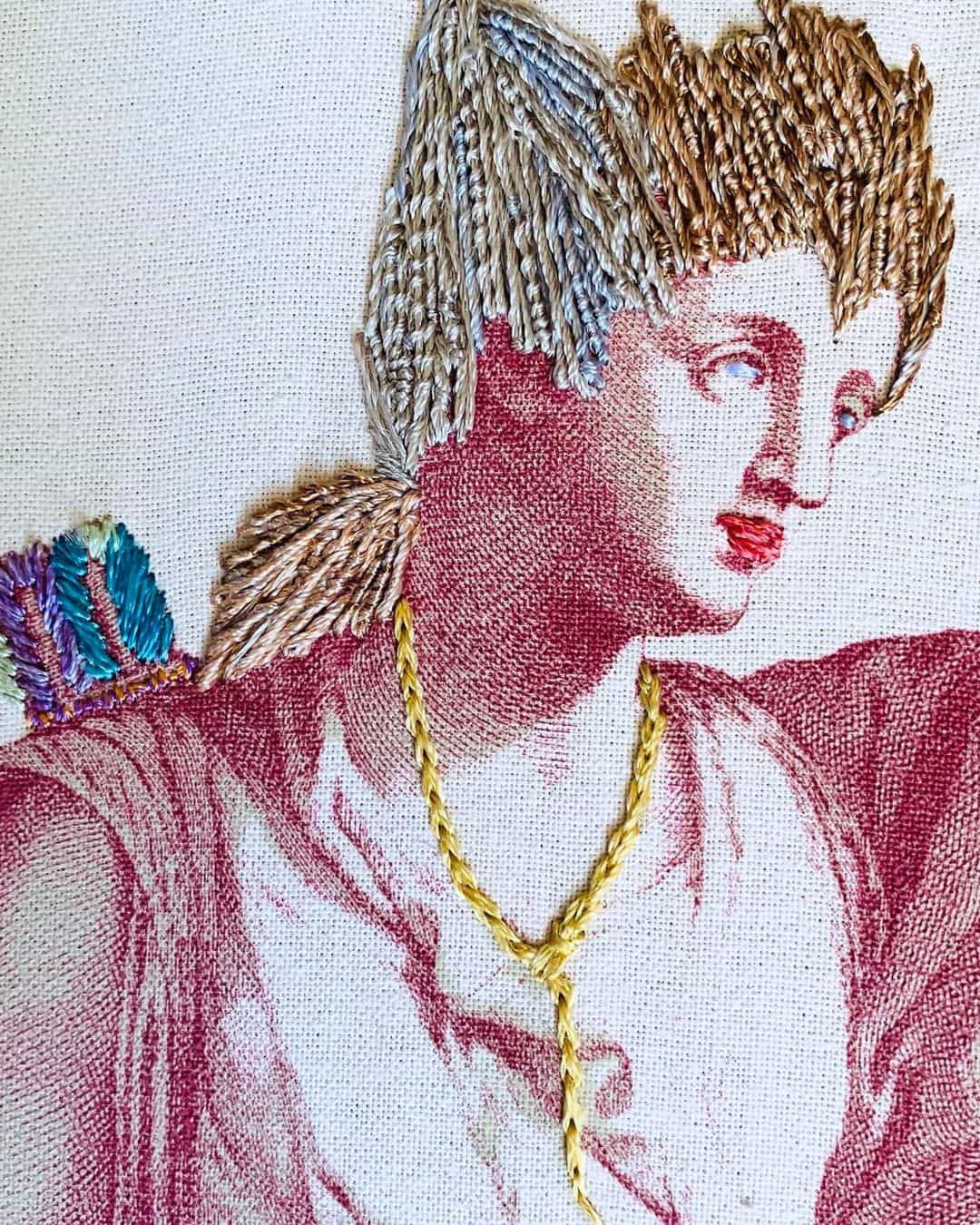

Subversion reigns supreme in Richard’s embellished French Toile de Jouy work, complemented by a healthy dose of humour, and it’s wonderful. His goal is to create historically inaccurate decorative arts using centuries-old fabric designs.

Richard’s art comments on current social, political and cultural challenges. He also makes sure his overlooked and unusual characters rightfully take centre stage. Past and present are seamlessly merged through burlesque imagery and colourful storylines.

Richard’s work is all about the details, so come and take a closer look – you’ll find something new every time.

Pillow dreams

Richard Saja: When I was seven or eight years old, I was given a box of Crayola iron-on transfer crayons as a birthday party prize. After a brief period of trial and error, I took a T-shirt and painstakingly recreated the Star Boy costume from the Legion of Superheroes.

But it wasn’t until after high school that I decided to introduce myself to art and the creative process. I had floundered around a bit in New York City and later in Philadelphia. I had always been drawn to pattern and texture, so I enrolled in a surface design class at the now defunct University of the Arts, Philadelphia.

I also took classes in ceramics at the Fleisher Art Memorial, and I loved building surfaces on clay. That prompted a move to New Mexico when I was feeling I needed to get off the East Coast.

While living in Santa Fe, a friend asked me to sit in on some classes at St. John’s College. I was blown away by their educational approach: all of the classes were seminar classes featuring student discussion and demonstration around an oval table – and no professors.

I graduated in 1993 and decided to teach myself Photoshop and Illustrator to add more skills to my arsenal. A couple of years later, I landed a job as the assistant to the creative director at an advertising agency on Madison Avenue (NY).

I worked at the agency for a couple of years, and then a transformation happened. Armed with knowledge of surface design, a classical education and advertising experience, I decided to start a design company with a friend. We developed 10 different styles of decorative pillows, one of which was hand embellished Toile de Jouy.

The concept had occurred to me while waking from sleep.

We debuted the collection at what was then the International Gift Show, and right out of the gate, the embroidered toile garnered the attention of all major design publications, as well as The New York Times.

“Out of necessity, I had to teach myself how to embroider to fulfil all our orders.”

Richard Saja, Textile artist

The company lasted a few years, but as my needlework skills improved, I decided to frame the pieces and introduce them into a gallery setting. That, too, took off almost immediately.

Historically inaccurate

Subversion is a key goal in my creative process. With an economy of means, I can change something historic and make it a little more rebellious.

Selecting specific areas of a traditional toile print to embroider over automatically subverts its intended use, by breaking the anonymity of the pattern. Suddenly, with stitches and colour, motifs are brought to the fore, demanding attention for my social, political or cultural statements.

“My work isn’t interesting to me if it’s not amping it up a couple notches.”

Richard Saja, Textile artist

From the beginning, my work has explored a myriad of themes of interest at the moment. They can range from ecological collapse or manmade disaster to trans visibility or the rise of neo fascism. The canvas mirrors my life experience and thought process.

Early on when I coined the term ‘historically inaccurate decorative arts’, I realised people liked to discover the humour for themselves. Subtlety was more important than didacticism or instruction.

Any message I’m attempting to address and imprint on a viewer will more likely hit its mark if the viewer is an active participant in their own discovery.

The funny side of toile

I’ve always responded to humour that’s considered dry-witted and spontaneous. Toile de Jouy just seemed like it was ready for some kind of reworking. Embroidery was the easiest way for me to do that.

The marriage of past and present creates a frisson and births something very new.

“There’s also something appealing about bestowing my imprint upon a textile pattern that has been around for hundreds of years.”

Richard Saja, Textile artist

Aubusson stitching

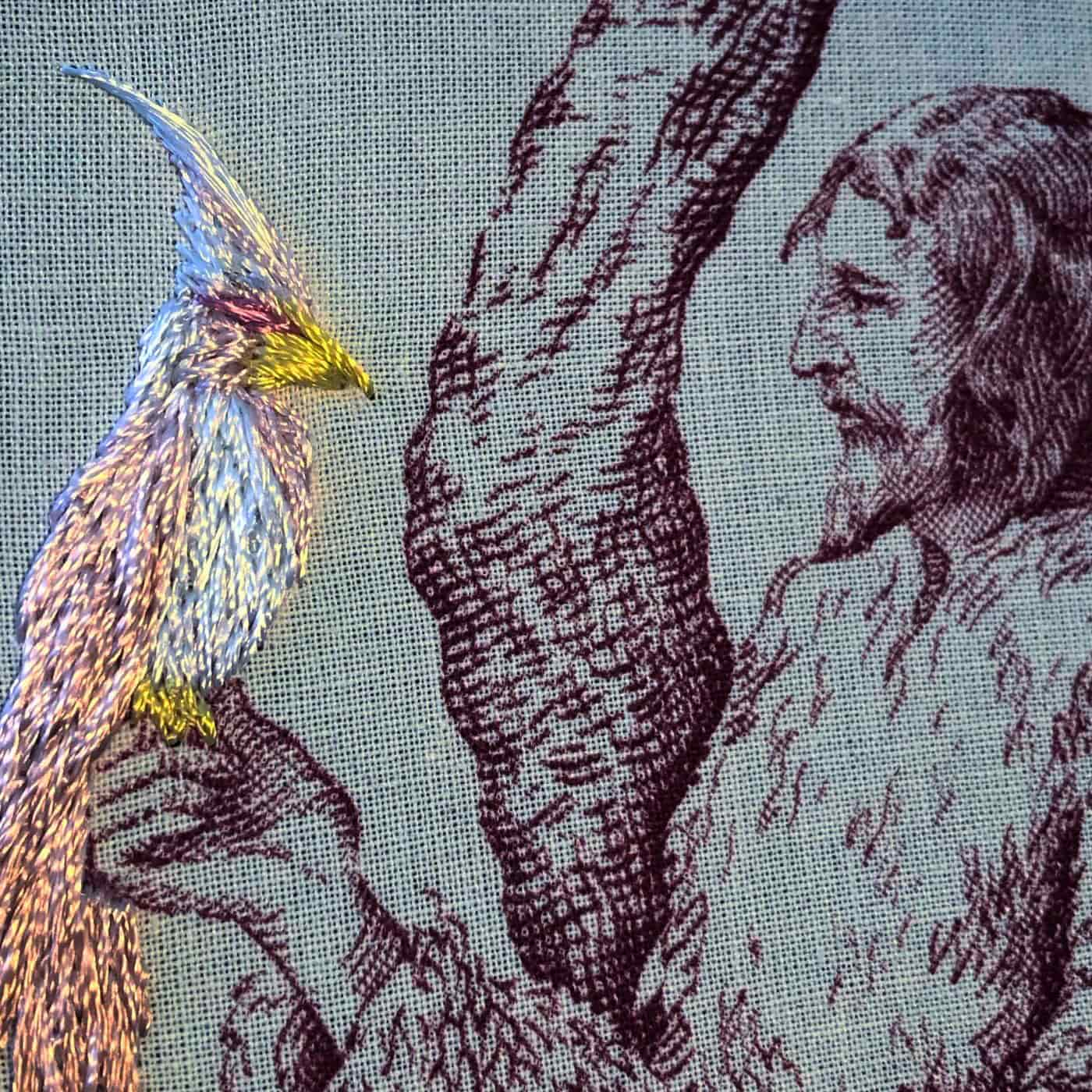

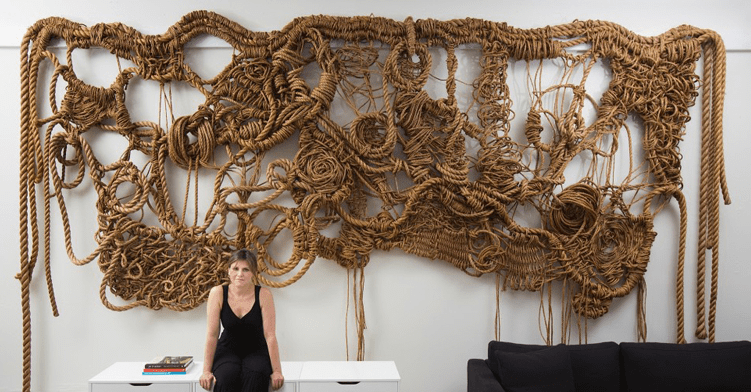

For the past 12 years, I’ve also been embroidering over Chinese Aubusson tapestries. This has made me see the close bonds between embroidery and knot making, and I’ve been pursuing and exploiting this relationship ever since.

From what I understand, weavers from France went to China in the 70s and taught their techniques to villagers in an attempt to keep prices low and production high. These Chinese Aubussons are fairly plentiful and largely inexpensive. That connection to French weaving was a natural progression from my Toile de Jouy work.

“For the Aubussons, my needlework is scaled up 1,000 times because of their size.”

Richard Saja, Textile artist

A couple of months ago, I was diagnosed with carpal tunnel syndrome. Although my unconventional conventional embroidery wasn’t fully affected, I found it somewhat easier to stitch using a thicker needle and perlé cotton over these wool wall tapestries.

At a certain point, simple stitches take on the form of knots sitting on the surface of the fabric. And because of the size of the tapestries, my needlework needs to be immaculate because errors are visibly evident.

Creative process

Generally, I start by selecting my canvas, whether it’s yardage of Toile de Jouy or a wool Aubusson tapestry. I pick a palette of complementary colours, arrive at a concept and begin stitching.

I rarely plan out specific embroidery – I prefer spontaneous results.

“My approach is to add context through embroidery.”

Richard Saja, Textile artist

For Toile de Jouy, I usually work with prints featuring figures sized 18cm to 30cm (7″ to 12″), as the stitching has little impact on anything smaller. Scale isn’t an issue, though, when working on the tapestries because the imagery is already quite large.

I work with a hoop, and I mostly stitch over historically based reproduction prints. But I’ve also worked with other artists on custom prints where I essentially art-direct a print using their drawings.

On custom prints I’ve designed myself, I use embroidery more as embellishment, as the context is already apparent in the print design.

A simple stitch palette

My most-used stitches are a basic running stitch, french knots, bullion stitch and chain stitch. Being wholly self-taught, I don’t profess to be a technically accomplished stitcher. Thus far, the possibilities seem limitless, and I feel my joy is imbued into the work.

“I find great joy and satisfaction in developing new and usually very interesting interactions among these few stitches.”

Richard Saja, Textile artist

When it comes to thread choices, I like using Anchor Marlitt viscose rayon threads for embroidering on Toile de Jouy. They’re rich in saturated colour and don’t easily fray.

For my Aubusson tapestry work, I only use DMC perlé cotton. Those threads are very durable, come in a gigantic range of colours and contrast perfectly with wool.

Must-have tools

I use a pair of electrician’s scissors I found on the side of the road in the early 80s. They’re still sharp enough and perfect for embroidery because of the rounded contours of the blades.

I like my surfaces to be very taut, so I only stitch on Morgan no-slip hoops. These are the only hoops that allow for that without frequent restretching.

My studio is in my home, in a room originally meant to be the primary bedroom. The room gets full sun all day long, so the light is perfect for needlework. I sit in a custom Vermont Folk Rocker chair, made without arms so I can get my floor stand as close as possible for the hoop to rest upon.

Young Mr. Lincoln

A favourite work of mine is Young Mr. Lincoln.

Years ago, I was invited to participate in a show honouring the ongoing legacy and accomplishments of Abraham Lincoln. I first thought to decline, but when I put needle to canvas, I created an almost stunning likeness.

I called the piece Young Mr. Lincoln because it showed a different side of the venerated US president. It was more lighthearted and less careworn.

That work and my very first Green Man was purchased by the comedian and chat show host Graham Norton. Of all my pieces, I wish I still had them in my possession. Interestingly, both were very basic embroideries.

Challenging stereotypes

It seems regressive to me to approach someone’s work because of their gender, so whenever I’m asked what it’s like to be a male in the textile art world, I shut down that line of questioning.

I’m much more concerned with the ‘what’ than the ‘who’, and I look forward to the time when people are rewarded by their fans and peers because of the quality and universal themes presented in their work. Not simply because of who they are.

“Social progress will never occur so long as the long under-represented continue to ape the same tactics of their oppressors to effectuate change.”

Richard Saja, Textile artist

Another challenging stereotype is the fact embroidery is rooted in the craft tradition. It’s not considered to be ‘fine art’, but I’m very happy to see that attitude steadily changing. Tons of textile work is now being prominently featured in museum exhibitions, galleries and art fairs.

It’s been a long time coming. And happily, the younger generations seem little concerned with the tired and resolution-less art versus craft conversation.

Find your own artistic voice

In an age when we relentlessly encounter imagery, I think it’s of paramount importance that young artists develop their own visual vocabulary to set them apart from the herd.

It’s quite easy to become tempted by trends or to rely too strongly on already established pop culture tropes. Those should only be used as an initial springboard to something more wholly personal and emblematic of each artist’s persona and experience.

Power of social media

I am very pro social media and feel somewhat sorry for those who resist it. I also think the value of hashtags shouldn’t at all be underestimated when posting.

Social media exposes my work to literally thousands of people from all different backgrounds, including people who may not have the resources to purchase textile magazines or be within travelling distance of museums or galleries.

I also find it immensely rewarding when I see comments on my posts mentioning how my work has inspired viewers. Instagram has also been hugely instrumental in prompting new commissions and exhibition opportunities for me.

“I spend most of my work time stitching alone in a room, so to receive recognition can be a big boost.”

Richard Saja, Textile artist

14 comments

Cre8iveskill

Richard Saja’s work is such a brilliant fusion of tradition and rebellion. His use of embroidery to reimagine historical patterns is both witty and thought-provoking. Absolutely love how he challenges the expected through every stitch!

John Robert

Bet we had a class or two together at St. John’s.. monotype? Jewelry? Who nose? Love your work – brilliant

Hilaria

Absolutely wonderful! I love embroidery and textile arts from all over the world. This is just a great addition.

Claire Riggall

When l first saw Richard’s work in Leanne Praine’s book Hoopla it blew me away. Years later it is still one of my favourites for its colour and surprise.

Beverley Scheurer

Just fabulous, funny and skillful!!!! A lovely article to be inspired by, thank you.

Christine Strong

It would be nice to see Richard Sajas work. There is nothing here about it other than his name and 1 interesting picture.

Deborah Haviland

I just read a lengthy article about the artist’s work with many photos. Maybe you can restart your device and try again. ?

Heather Phillips

As a painter, printmaker, textile artist, with experience of workshops but years of self teaching, I am I total awe of Richard’s work. Sadly I now live in an area where it’s difficult to get anywhere, so am glad to have this opportunity to see other artists’ work.

Lesley Jackson

I love this, the colour, playfulness and inventiveness. I have always loved embroidering over designs but this takes that idea to another level. If you are reading this Richard, please put in brackets, in the text above, how to pronounce ‘Toile de Jouy’ and tell us what the term means. Is it ‘playful work?’

Diane

Jouy is simply a place in France where this type of fabric was created.

From Wikipedia:

The French “Toile de Jouy” simply means “cloth from Jouy” in English and describes a type of fabric printing.

Jen

WOW , RICHARD ,

WOW , WONDERFUL , INSPIRATIONAL , Richard !

Helen Scalway

Love his inventiveness and freshness of vision towards very traditional fabric designs.

Helen Scalway

I really love his inventiveness.

Nathan Philips

This article on Richard Saja’s work is fascinating! His approach to subversive stitching adds a unique layer of meaning to traditional textile art.