When you see an artwork stitched with human hair, does it make you want to take a closer look, or does it repulse you?

It’s a dichotomy that Rosemary Meza-DesPlas has often witnessed as visitors peruse her works stitched with her own hair.

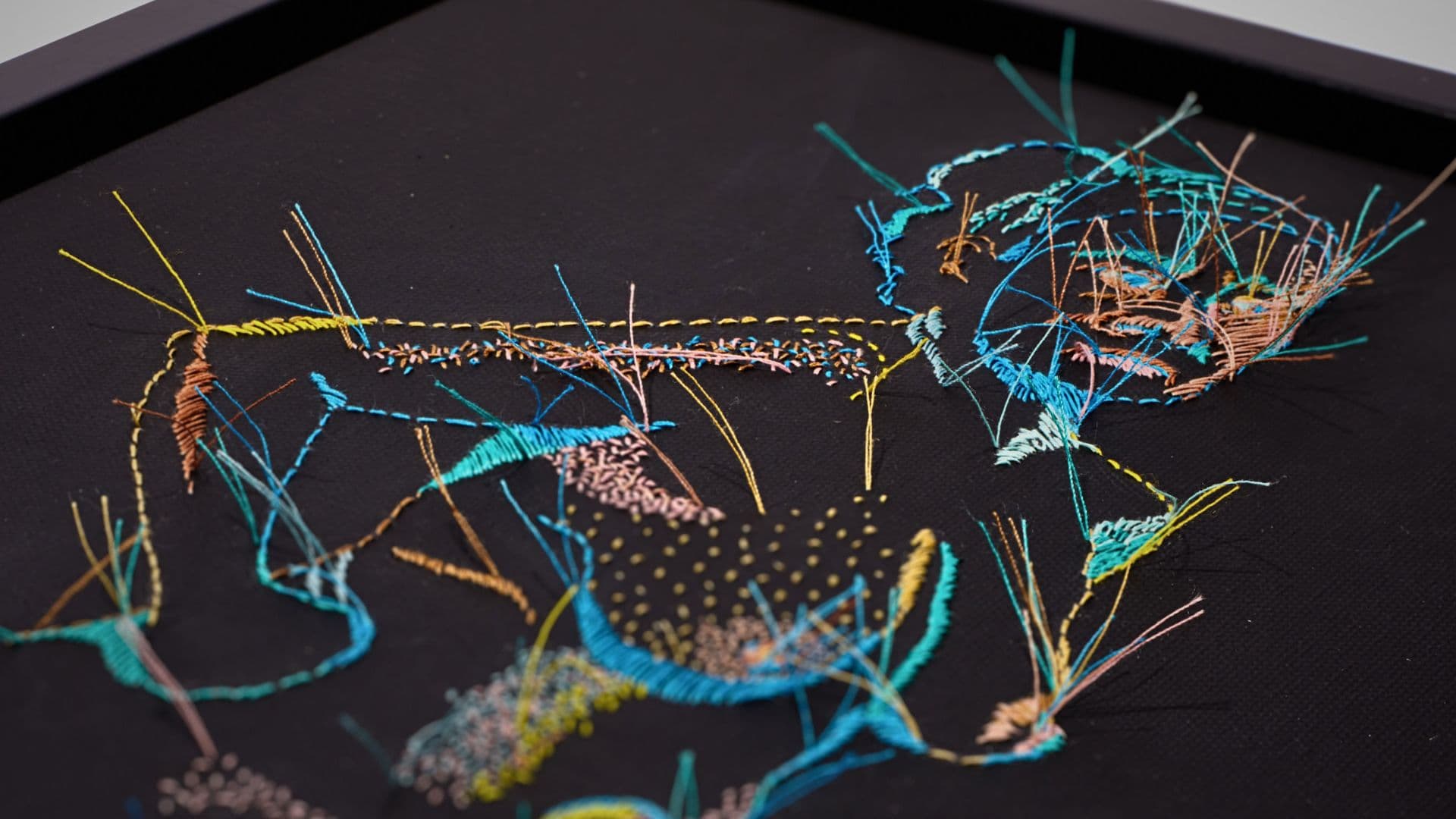

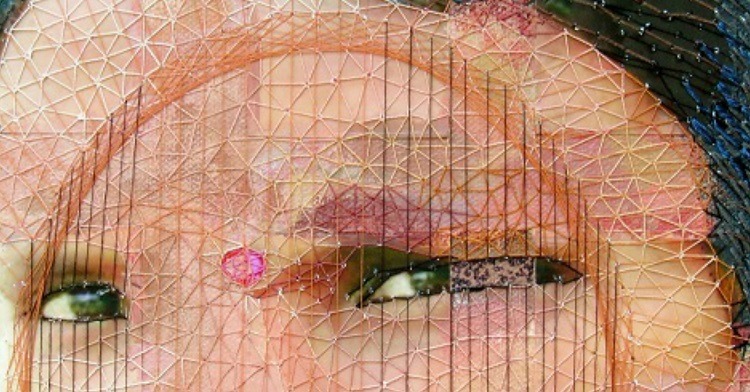

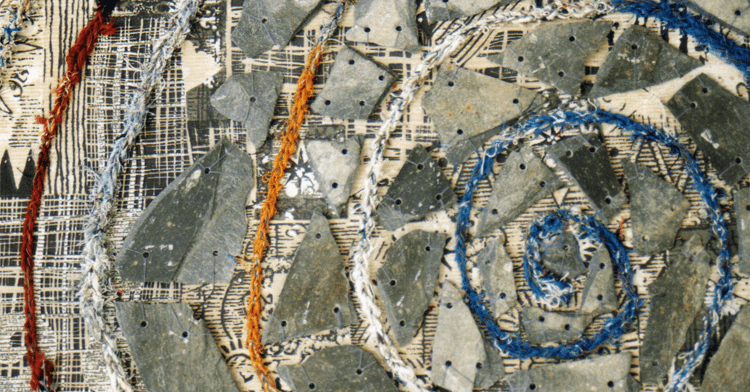

Rosemary incorporates fibre art, drawing, installation, painting, performance art and video into her studio practice. But in 2000, prompted by a friend’s suggestion, she started gathering her hair to produce artworks stitched solely in this material. Recent works have intertwined hand-sewn human hair with watercolour, thread, speciality fabric and collage.

Why stitch with hair, you might ask?

Rosemary recognises the relationship between the qualities and symbolism of hair with issues of body image, femininity and identity. Her mother and aunts had migrated from Mexico across the United States as a family of agricultural labourers, and, as Rosemary pondered the hardships they endured, she committed to exploring these feminist issues.

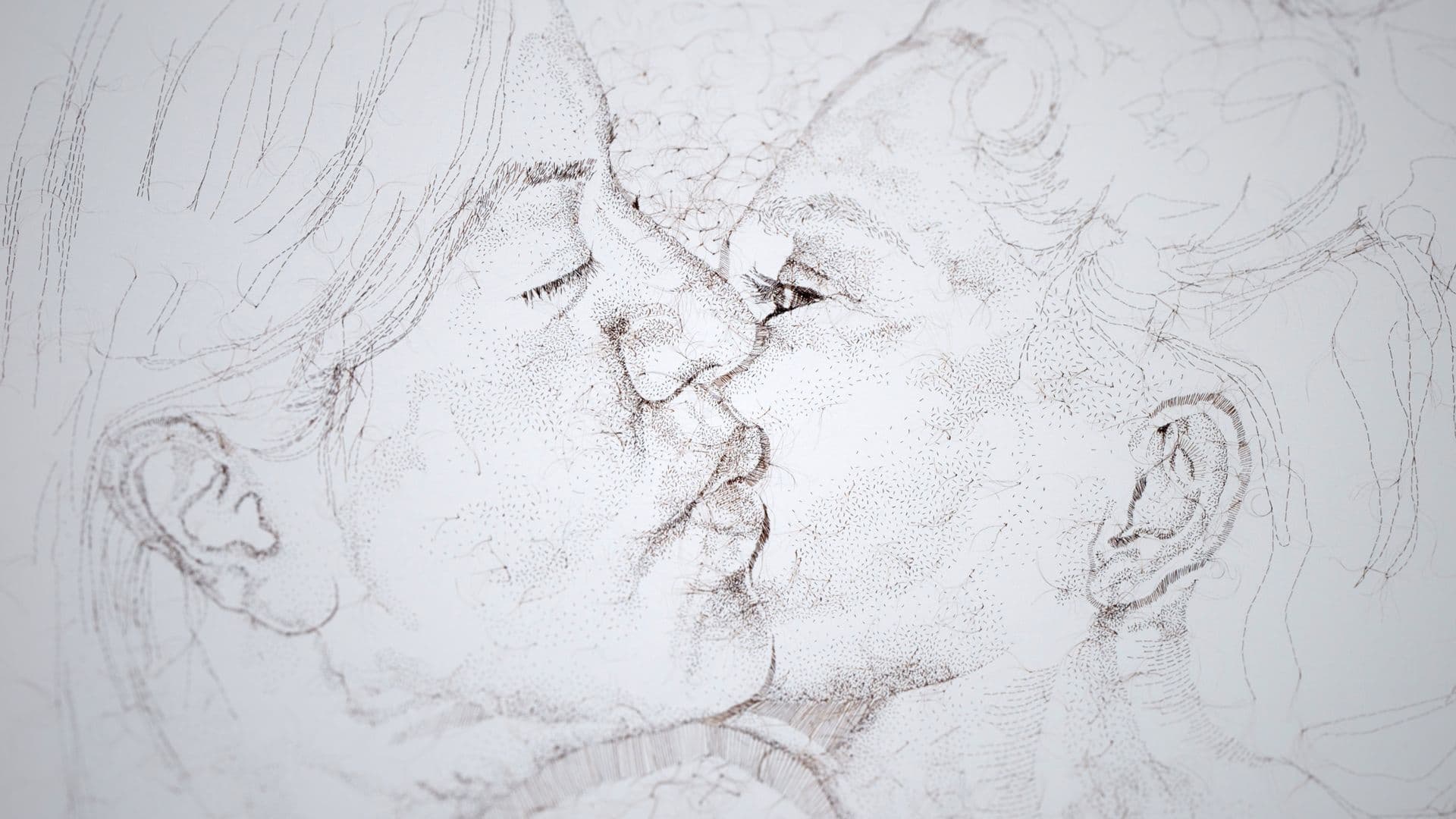

Since then, her artwork has been thematically centred upon women: their narratives, societal challenges and resilience. Hair is the perfect material and the human form the perfect image.

Experimenting with hair

What made you decide to stitch art using your own hair?

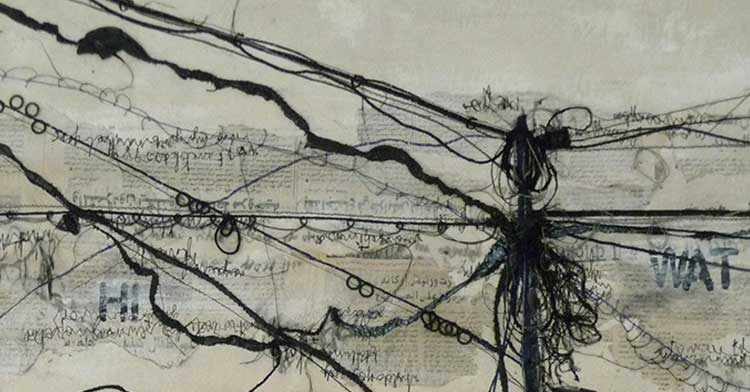

Rosemary Meza-DesPlas: I started working with my hair after an artist friend suggested the line work in my wall drawings correlated to human hair. She equated the scratchy and undulating lines on the wall to the texture of hair.

I became intrigued by the idea of utilising hair in my art and so I spent time experimenting with it. It resulted in trial and error: glueing it to paper was messy and unruly.

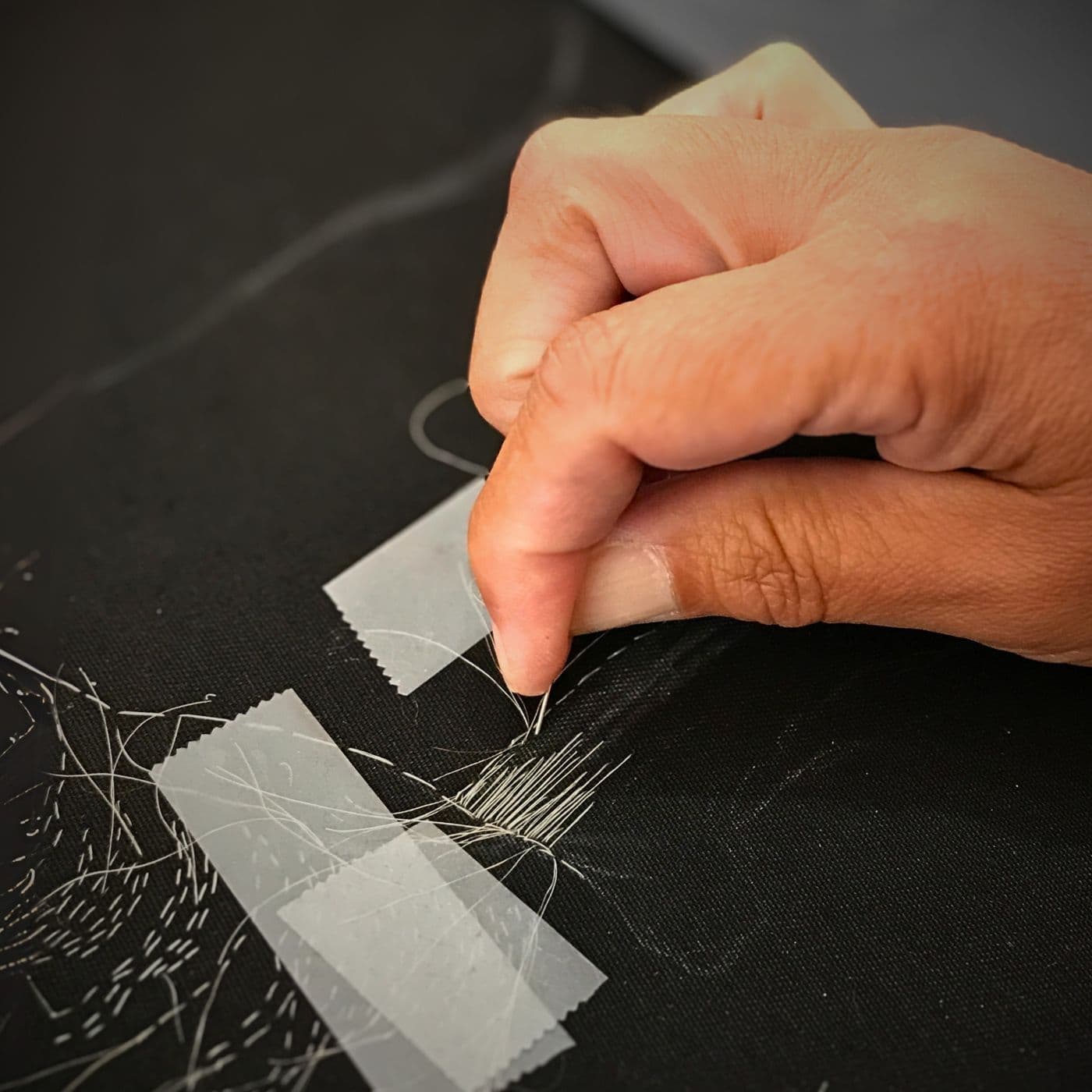

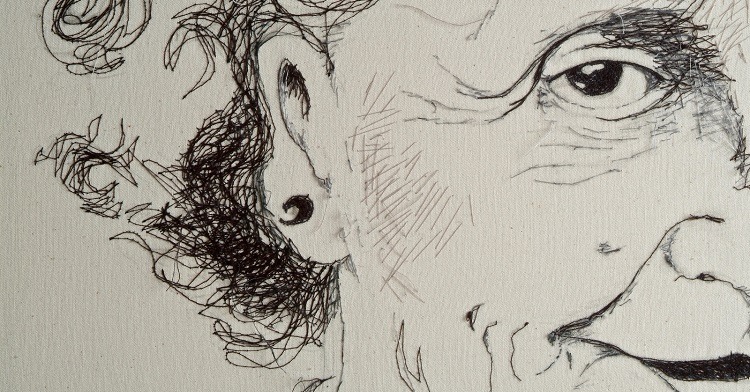

I have academic degrees in drawing and painting from the University of North Texas and Maryland Institute College of Art, respectively. When I tried sewing with the hair, I found it allowed me to translate drawing techniques – such as hatching, stippling and cross-hatching – into stitches.

I haven’t been trained in sewing hair – I’m self taught. My mother and aunts learned to sew due to the economic challenges and scarcity of resources. As a child in the 1970s, I wore shorts and shirts made by my mother from Simplicity patterns. But neither my sister nor I were interested in picking up basic sewing skills.

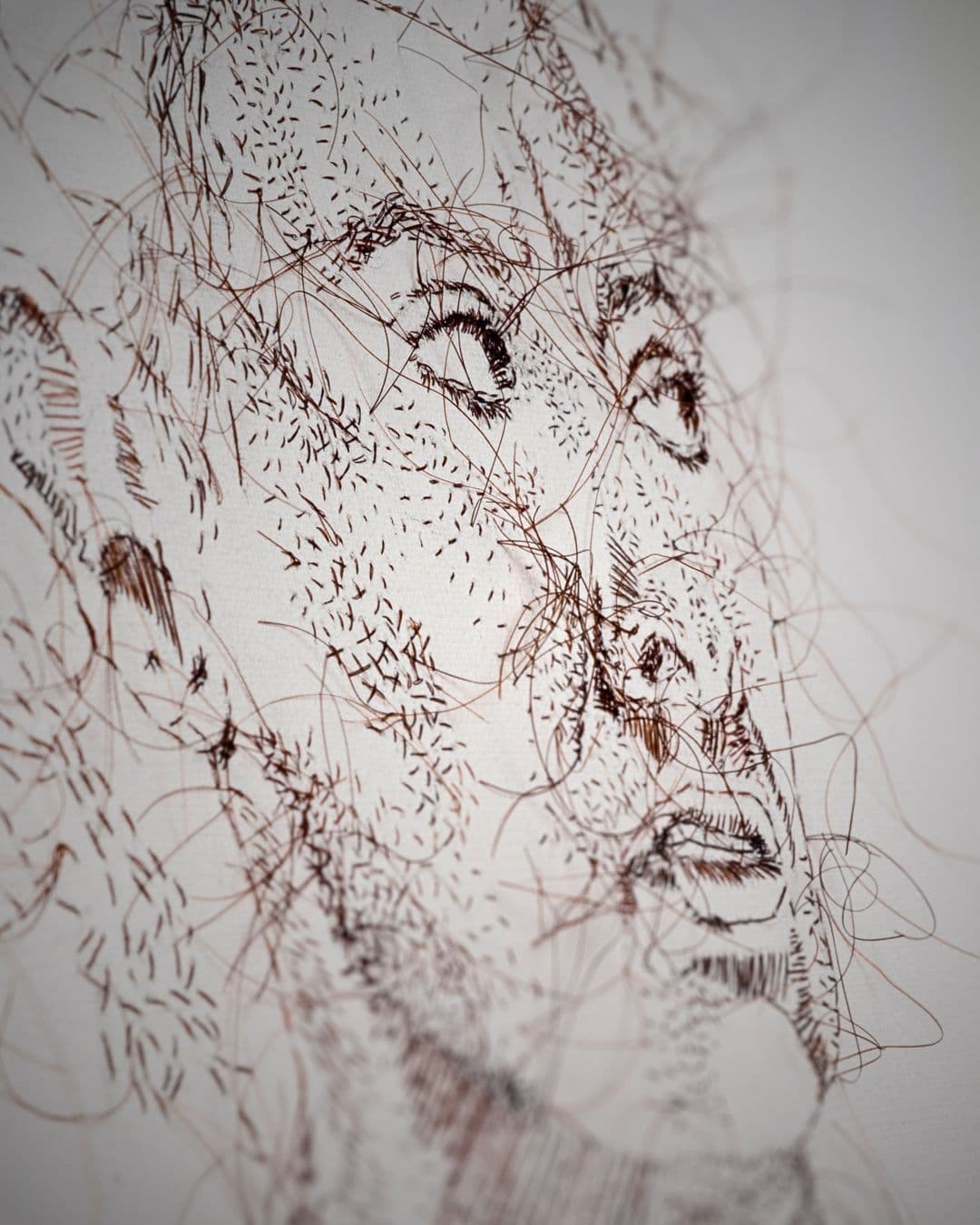

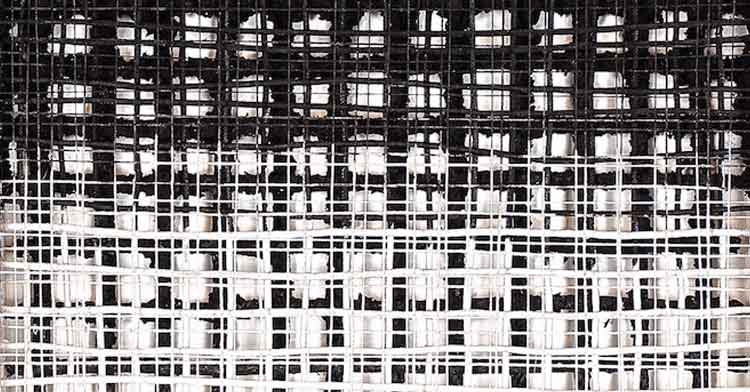

My first few hair artworks were graphite and colour pencil with just a touch of hand-sewn human hair. After becoming more confident with sewing the hair, I’ve created subsequent artworks completely with hand-sewn human hair.

In 2002, I began to embed these artworks into three-layer resin casts. Some recent works have intertwined hand-sewn human hair with watercolour, thread, speciality fabric and collage. Since 2018, I’ve made hand-sewn human hair artworks with my grey hair.

The symbolism of hair

Sociologist Rose Weitz published a work called Rapunzel’s Daughters: What Women’s Hair Tells Us about Women’s Lives. She examined the hair’s relationship to sexuality, age, race, social class, health, power and religion.

Hair conveys symbolism in literary works such as the short story The Gift of the Magi by O. Henry, The Rape of the Lock by Alexander Pope and Rapunzel by the Brothers Grimm. There are religious connotations to hair, which coincide with symbolism reflecting strength, sensuality and reverence: Delila cut off Samson’s hair and Mary Magdalene washed the feet of Jesus with her hair.

“I like the dichotomy of using hair. Hair can be sexy and engaging to people; on the other hand, it can be repulsive.”

Rosemary Meza-DesPlas, Textile artist

Consider finding a hair in your soup or a hair on your hotel pillow. When viewers see the works in person, the imagery beckons the viewer to move in closer. I’ve seen gallery patrons impressed with the technique, yet repulsed by the material.

Repurposed materiality

Transformation of hair into artwork is repurposed materiality. Materiality of hair coincides with feminism at the point it speaks to issues of body image, femininity and identity.

Due to its correlation to material culture, hair may reflect political agency. In 2022, women filmed themselves cutting their hair; ordinary actions became acts of protest. Hair for Freedom showed solidarity with Iranian women and protested the death of Mahsa Amini.

Crafted hair in contemporary artwork can be interpreted as exoticizing women, ritualistic movements, critical gendered commentary or multidimensional stories.

“The materiality of hair coincides with feminism and ethnicity at the point it speaks to issues of body image, femininity and identity.”

Rosemary Meza-DesPlas, Textile artist

Feminist ideology

Tell us how the tenacity of your eight aunts contributed to the feminist ideology that you express in your art…

My mother comes from a family of eleven; eight out of the eleven siblings are women. Her family, originally from Allende, Mexico, travelled across the United States as agricultural labourers. The migratory existence was difficult for the women. Family stories have given me an appreciation and understanding of the hardships they endured as women.

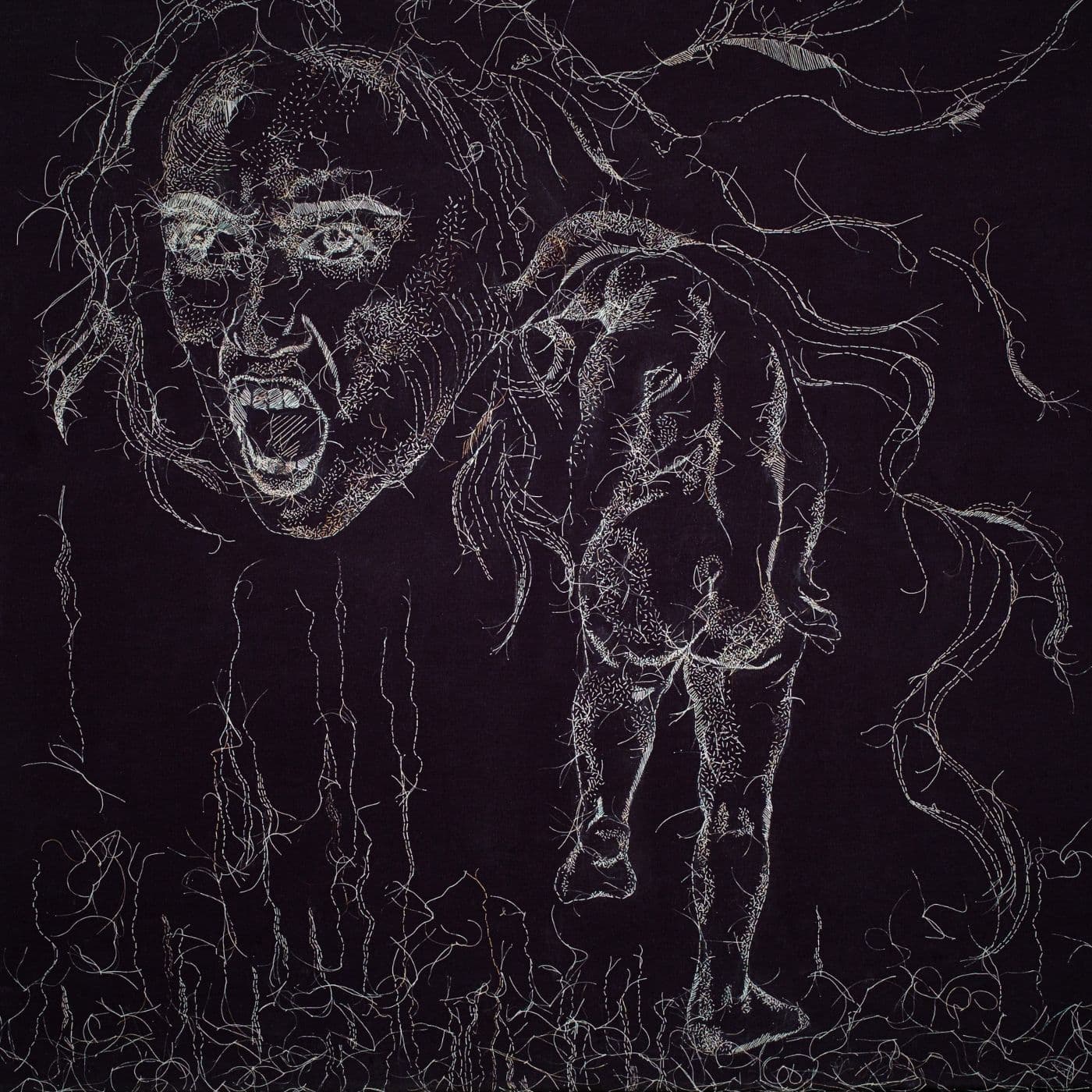

My artwork has been thematically centred upon women: their narratives, societal challenges, and resilience. The female experience within a patriarchal society is one of inequality.

From brunette to grey

What were your feelings as you went from brunette to grey, and how did this affect your hair art?

I’ve been collecting my hair daily since 2000. Collection of hair is a ritualistic activity; I gather it by running my fingers through my hair each morning or by accumulating that which falls out during a shower.

There’s a meditative quality to sorting hair as preparatory work. I enjoy the texture of the hair through my fingers. I slide my fingers down its length and create work piles correlating to length.

Over the years, I’ve dyed my hair different shades of brown and red to obtain a greater variety of values and tones. When my hair began to grey, I would dye it. Colouring my hair was an act of vanity. The grey was visual evidence of my ageing process.

“At the point I stopped dyeing my hair, I came to terms with time’s salt and pepper paintbrush.”

Rosemary Meza-DesPlas, Textile artist

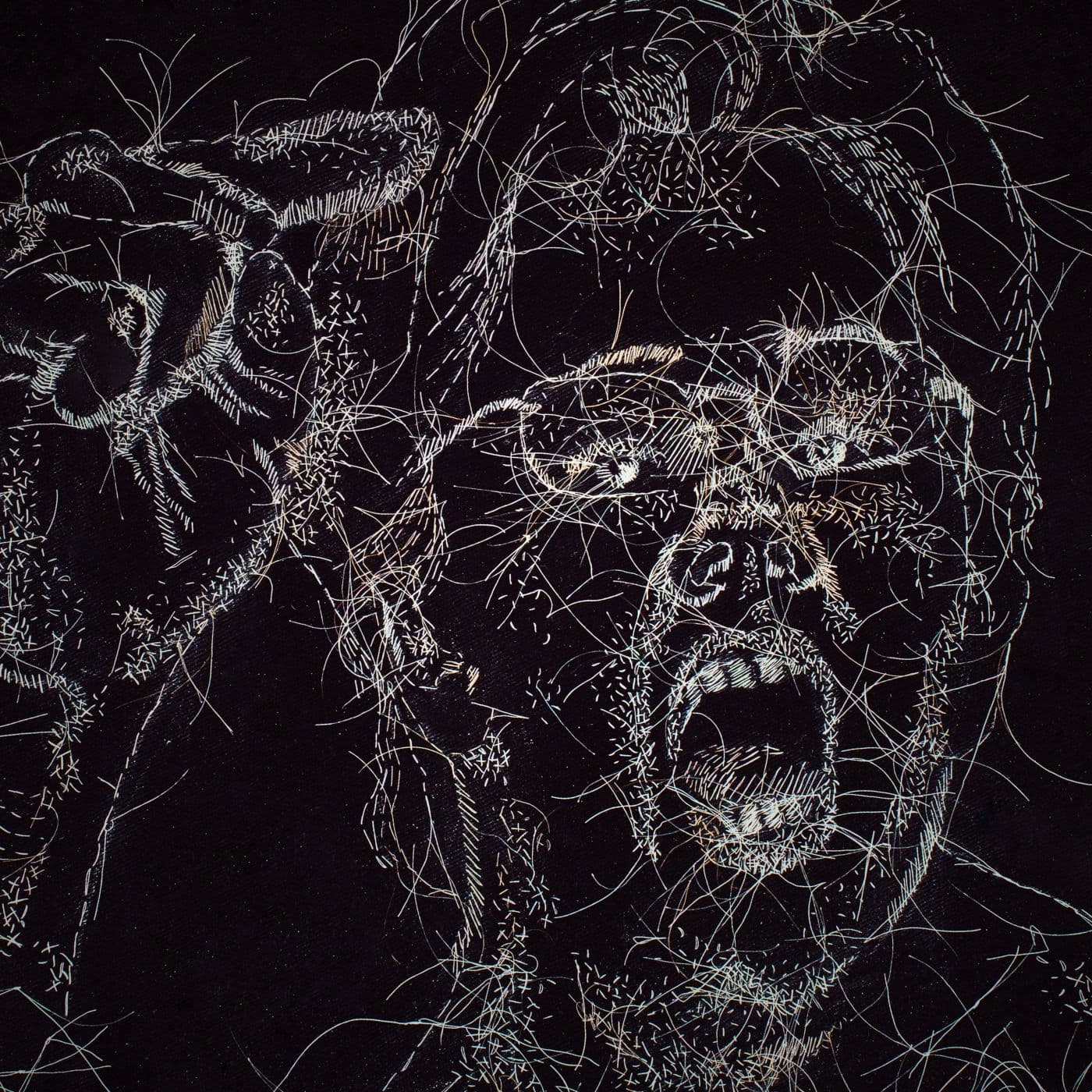

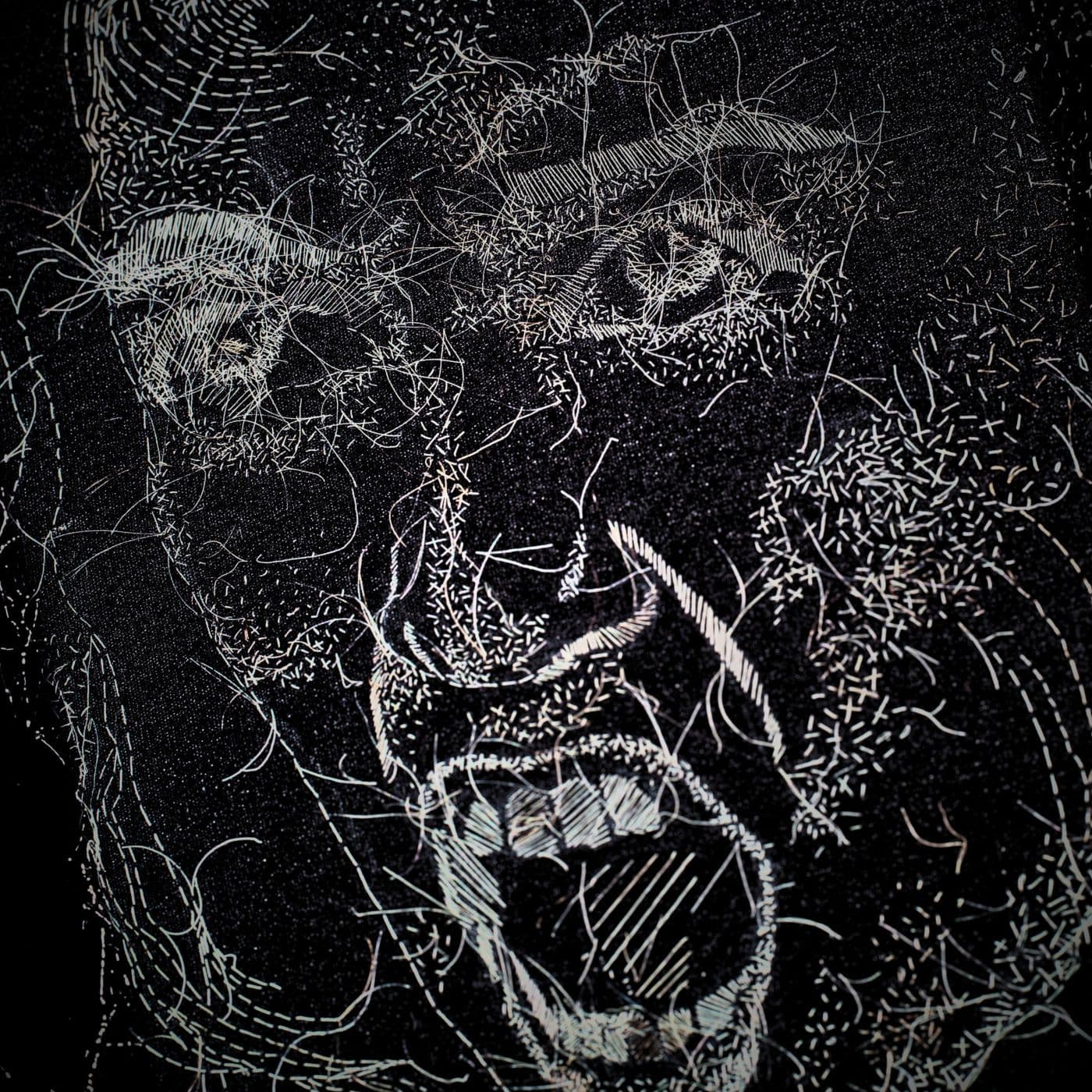

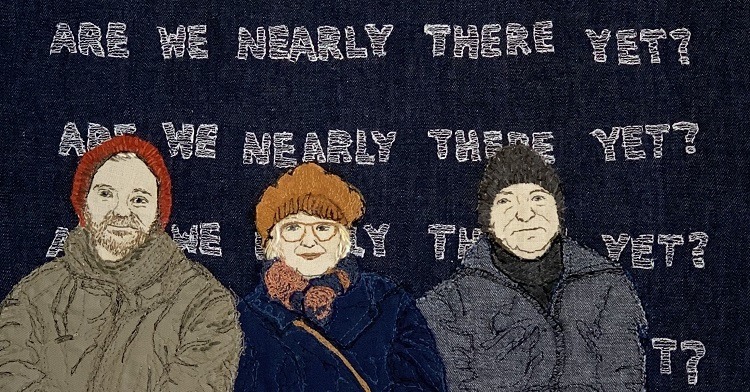

My greying hair became another art material to experiment with in my studio. Incorporating grey hair into my practice involved trial and error; therefore, I began a quest for the appropriate ground fabric. I currently use a black twill fabric. The texture of the grey hair is coarser and easier to manipulate.

Sketching and stitching

Tell us about your process and techniques when you’re working on a new piece.

Once I’ve collected my hair, I store it in plastic bins referenced by colour or year. At the beginning of a day’s work, I create piles of hair correlating to length: short, medium and long. These work piles of hair are then ready for me to use.

I select my needles according to the ground I’ll be working on. Some of the grounds I’ve worked upon include mylar, vellum, parchment, stretched watercolour canvas, chine-collé paper, stretched oil canvas and raw unprimed canvas.

I then create a gestural sketch of imagery on the selected ground. The sketch is usually created with an H pencil; however, I’ll use a white pencil for the black twill fabric.

This preliminary sketch is necessary because sewing hair is an unforgiving medium. Once the hair is sewn it can’t be undone. The removal of stitches leads to gratuitous holes and a blemished appearance.

“As I stitch my hair into the surface with a needle, I create a variety of values which serve to define the imagery.”

Rosemary Meza-DesPlas, Textile artist

Closely stitched lines or darker hair strands correlate to dark value. Sparsely spaced lines or a lighter brunette hair equates to lighter values. Drawing techniques, such as hatching, stippling and cross-hatching, translate to stitches.

Depending upon my intention, techniques are varied to achieve a range of textures, values and emotions. My academic degrees in drawing and painting mean that my technical approach is drawing-based.

As I sew the value patterns across imagery, I erase the initial gestural drawing. Visually, the end result is solely embroidered hair.

Tying off the hair when I am done sewing a section involves leaving the strand long; the hair protrudes from the surface. This interaction of hair and negative space creates a three-dimensional appearance. Initially, I tied off the hair and closely trimmed it to the ground; however, by 2011 I began leaving the tied-off strands long.

Human figures

How does your hair art fit in with your other work?

I incorporate fibre art, drawing, installation, painting, performance art and video into my studio practice. The human figure is the unifying image in my artwork, notwithstanding what medium is being used. Thematic continuity links my visual artwork with my academic writing and poetry.

The installation artwork, Groundswell, that I set up in 2020 in the Amos Eno Gallery in Brooklyn, New York has hand-stitched hair around its border. The smaller elements of it contain hand-sewn hair.

My performance artwork encompasses the creation of costumes. The skill set from sewing hair is applied to sewing the costumes for my performances.

Hair as archive

How has your hair artwork developed over time and what direction do you think it will take in the future?

The hair artworks have served as an archive of my body and ageing process.

I prefer not to speculate as to what direction future works might take. Studio experiments are predicated on freedom. Presupposed outcomes can hem in latitude, restricting future choices.

Drawing and exploring materials

What advice would you give to an aspiring textile artist wanting to try out your kind of materials and techniques?

If an aspiring textile artist wanted to use my drawing techniques, I would recommend they take college-level drawing classes including figure drawing. Experimentation, research and study of materials are also integral to my studio work.

New ways of making art invigorate my practice; thereby, the visualisation of thematic issues becomes innovative. I move comfortably between varied materials to create art.

“I am a process-oriented artist who finds personal growth within the investigation of unfamiliar materials.”

Rosemary Meza-DesPlas, Textile artist

2 comments

Theresa Watson

Your work is very delicate and does have the feel of an etching or an old master. Also good to see hand stitch.

Theresa Watson

I love the fragility of the finished pieces which gives it tge feel of some great timeless age. I always prefer to see hand stitch anyway. I feel that the work is meditative, mist lijely the process takes over from the initial sketch; leaving the threads adds to the work’s success.