Investigate the work of Sharon Peoples and you’ll discover a menagerie of wonderful creativity, ranging from small stitched portraits to delicate embroidered lace works.

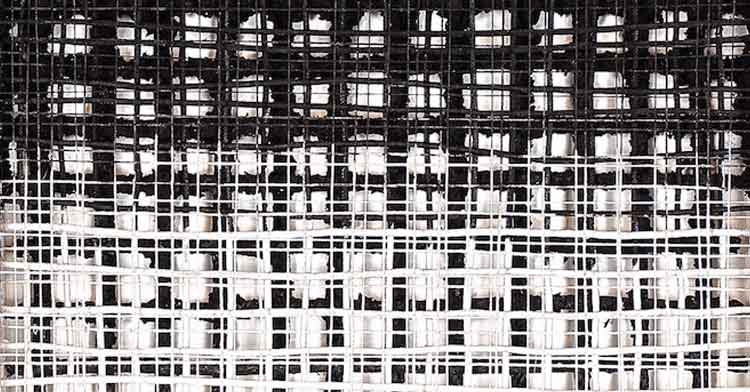

Through her machine embroidered lace technique, Sharon’s delicate machine-stitched works express the fragility of the environment.

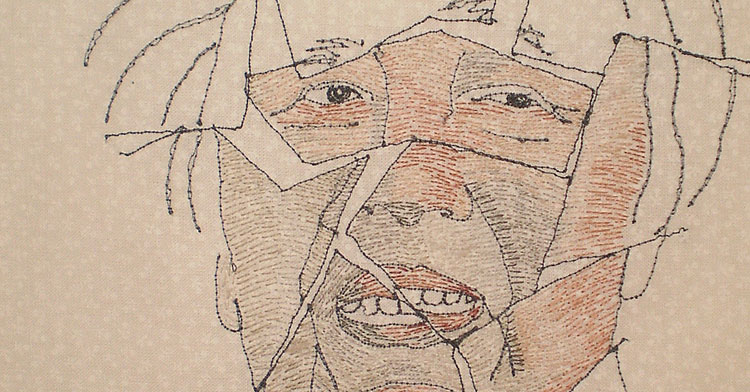

And in her miniature portraits, cross stitch is released from the confines of the traditional approach of counted designs. The random stitches allow complex colour blending and layering. These small works are intense, yet intimate. Sharon stitches scenes with contrasting areas of dark and light, and often she stitches on dark fabrics.

The idea of using a dark background for her portraits comes from Sharon’s love of traditional Swedish yllebroderier. Adapting this technique to make it her own, she stitches small vignettes of ‘thinkers’, people in their own moments. We can only guess what is on their minds.

These cherished snapshots of time are often placed into containers, transforming them into tiny treasures.

While the techniques and materials may vary, her love for embroidery and layers of stitch, whether by hand or machine, is what ties her work together. Sharon always matches her artistic approach to the story she wants to tell – the medium is the message.

One artist…two styles

TextileArtist.org: Which techniques do you use?

Sharon Peoples: I am both a hand stitcher and a machine embroiderer. These are two strands of my work, and each strand responds to different ideas. I always ask myself ‘Why am I embroidering this?’ as well as ‘How?’. I work out which process will be the most suitable or convincing.

I am a strong believer in the idea of using the medium as the message.

In English, to embroider a story is to elaborate, expand or embellish. And so if my work is about a narrative, I generally use hand embroidery. My machine-embroidered lace tends to reflect fragility of both the environment and the human condition.

When thinking of the very large historic embroideries, like the Bayeux Tapestry, the marks of the stitchers, restorers and menders stand to illustrate the repair, care and protection that is required for the environment. Hence, I use embroidery as a metaphor for repair.

I don’t necessarily have a clear-cut recognisable style, as such. But I embrace that my work is diverse. As a teacher of embroidery, I need to be able to master many techniques to pass onto my students, and this influences my work.

My lace pieces are machine stitched onto soluble fabric. This technology behind this fabric has improved vastly over the years. One thing that influenced my experimentation was it was much cheaper to buy a 100-metre roll online. Because of this, the soluble fabric lost its preciousness. I played around much more and pushed the boundaries of how it could be used.

I draw or trace designs onto the soluble fabric with a Frixion (friction-erasable) pen. The danger with this technique is that excess heat can make the lines disappear. But I love technical challenges.

I like to include small pieces of fabric within the machine embroidery. These have a piece of double-sided fusible webbing (such as Vliesofix or Bondaweb) attached. I dry-iron these onto the soluble fabric, avoiding direct contact, using a tiny iron that doll makers employ.

Once the work is embroidered, I check that all the threads are connected, and pin it out on a board covered in baking paper, ready to rinse and dry.

Tell us about your machine-embroidered work, The Seaweed Collector

The Seaweed Collector is a portrait of a good friend, the artist Julie Ryder. Julie is incredibly focused, and research plays a major role in the artwork she produces. She has spent several years attempting to uncover details about the collectors of two 19th century seaweed albums held in museum collections.

She also collects seaweed herself. I have been with her a few times to collect the seaweed that she preserves and uses for dyeing textiles.

I saw a clear visual relationship between some of the seaweeds and her wild red hair.

First, I imagined I would ask her to lie down on the sand while I arranged seaweed around her hair, but the weather was not conducive to that. So, back in the studio, I went through my sketch books and found some little sketches I had made in Berlin, of faces with extraordinary head pieces.

Using these as inspiration, I photographed Julie but drew over the images so that she had closed eyes. I drew a mass of seaweed above her head to reflect her thought processes.

For this work, I decided to machine embroider on water-soluble textile to create a lace-like effect. I machine stitched a lot of sample works to audition colours and shapes, and created the layers of seaweed.

I experimented with different ways of drying the lace. Some were pinned flat and others allowed to curl. The process became very complex as I added more and more layers of embroidered seaweeds and sourced threads in the right colours.

I was excited by my work and felt I had captured Julie’s likeness, but the colours seemed way too dark. Despite the fact I had spent so much time on the portrait, I decided to repeat it, using lighter tones.

When it was ready, I invited Julie to view both portraits and I explained my decision to abandon the first version. I was nervous about showing her the portraits. But interestingly, watching Julie’s face as I turned her toward the embroideries, she liked the first portrait, saying it was as she imagined herself to look. That settled it. I took the lace and tacked it onto a backing ready for framing.

Hemslöjd and cross stitch

What inspired your random cross stitch portraits?

In 2015, I was lucky enough to travel to Sweden. I visited the Nordic Museum in Stockholm and really enjoyed looking at an exhibition on hemslöjd, roughly translated as ‘handicrafts made at home’.

The embroideries in this exhibition really enchanted me, and I bought the book Yllebroderier, edited by Annhelén Olsson (2010). It was in Swedish, with excellent photographs. To a certain degree, I could understand that it was a historical account of traditional embroidery.

When I returned to Sweden in 2019, through pure luck, I met an embroiderer called Lena Palenius, who stitches contemporary yllebroderier. She knew one of the contributing authors of the book, Eva Berg. Lena took me to a hemslöjd workshop and store near Lund in southern Sweden and introduced me to Berg.

I wanted to respond to this way of working after seeing the way in which Lena stitches. But not having any Swedish heritage myself, I contemplated ways of working that were meaningful to me. My limited understanding indicated that much of the traditional work marks particular occasions, like weddings, as well as the ordinary and everyday.

The work I have made responds to the Swedish style of stitching, but I doubt that people would make any link between my work and the traditional formats.

It is the dark fabric and the everyday scenes that are the link.

Generally, I am looking for a strongly lit figure, although placing an image on dark fabric can, in itself, be very dramatic. I often take photographs and convert them to black and white. This helps me to see if an image is suitable for working on dark fabric.

I like a portrait to tell a story and include some personal traits, as well as being a true likeness of the subject.

In my house I have a wall of photos of people lost in thought, which often end up as portraits. For example, I have a photo of a young boy who loves eating ice-cream, but tends to bite the bottom of the cone when no-one is looking. He ends up in a mess and then abandons the whole thing. The dog waits, knowingly, below. The image says a lot about the boy’s personality.

For these portraits, I use a linen background fabric and stranded cotton embroidery thread in a range of skin tones. I tack the design outlines first, using machine sewing thread. Then I use layers of random cross-stitch to fill in the light and dark areas, creating layers of shadow and light.

When using dark fabric, I start with the lightest coloured thread and stitch the lightest areas. I progress to the darker tones and colours, stitching a series of small haphazard crosses. The stitching can be dense or sparse, depending on the look I am after. When I stitch on black fabric, I seem to be able to stitch quite sparsely, allowing the black fabric to form the shadows.

I love to mount these miniature portraits in containers. And I am now curious to have a go at working this technique in wool threads, more like traditional yllebroderier.

The power of embroidered jeans

What initially attracted you to textiles as a medium?

I was first attracted to textiles as a child while learning to embroider a d’oyley (doily) kit. The design showed a posy of purple and mauve petals with yellow centres, to be filled with long and short satin stitches. The leaves were outlined with green stem stitch.

I remember my mother crocheted the edges for me. With six children in our family, one-on-one time with a working mother might well have been my initial attraction to textiles.

However, the unexpected arrival of my cousin Robyn in the early 70s really fired my imagination about embroidery.

Robyn arrived dressed in the most amazing and outrageous embroidered jeans that she had stitched while teaching in Mexico. They were wild!

After she left, I began embroidering my own jeans. One of my elder sisters was at art school and suggested I embroider her second-hand army jacket. The d’oyley kit was not touched again.

What was your route to becoming an artist?

Like many people of my generation, textile making was a part of the everyday, hence the embroidered jeans. However, my route to becoming an artist was circuitous.

I embroidered my way through the final year of high school. There were very few embroidery artist role models in Australia, so my undergraduate degree was in interior design. Then I married and moved to Perth in Western Australia.

As children were born, mermaids were stitched, clothing decorated and images of the local environment were embroidered. Interior design was parked in the garage.

A relocation to Canberra enabled me to embroider my way into a group of very creative women. They pointed me in the direction of the art school at the Australian National University. I went on to graduate with a masters from there, which set me on a career path in embroidery.

For a time I concentrated on being accessible to my teenagers, as well as meeting the demands of paid, part-time work. But I felt the need for stimulation so I went to study curatorship and art history, eventually completing a PhD in fashion theory. This led to work in the museum studies department and becoming chair of the local crafts council.

Then, missing my making, I began the task of resurrecting my arts practice, by taking short courses with Australian artist Ruth Hadlow and American artist Jane Dunnewold. Through Jane, I picked up the habit of daily journal writing and stitch meditations, which are both key for a really productive workday.

Tell us about a work that holds particularly fond memories?

Although not to my own design, my fondest memory is working on a 16m (53′) long embroidery for the new Parliament House in Canberra, in 1986. This project involved 498 embroiderers from across Australia.

As a young mother, I loved stitching away with the older women on the long frame. The women were highly skilled and most were vocal feminists. I still love taking visitors to Parliament House to see this impressive work.

I went on to design a 12m (39′) embroidery, in 2000, for our new National Museum of Australia, with local Embroiderers’ guild members stitching the work.

Artist Michelle Kingdom also creates small figurative vignettes using hand stitch. Read more in her interview, Michelle Kingdom: Exploring secret thoughts.

Discover the work of Yumiko Reynolds and how she uses her sewing machine to draw, in Yumiko Reynolds: Freehand machine embroidery.

9 comments

Loani

I am a hand embroiderer I am interested in machine embroidery but yet to incorporate it into my work.

Sharon’s work is inspiring.

Eileen Sainsbury

I am eager to see this workshop, Sharon’s works are truly beautiful.

Margaret Pratt

Wonderful inspiring work, such a creative use of cross stitch.

Margot

Absolutely stunning work

Helen Ruddy

Great article – thank you. I have a tip for pinning out embroideries on soluble fabric.

I’m not a big fan of plastic but have found using children’s ‘jigsaw’ floor tiles to be excellent for pinning out embroideries on soluble stabilizer. They are very inexpensive, with several in a pack. They are completely waterproof so you can pin out the embroidery before dissolving. The stabilizer never sticks to the tile so you can leave more stabilizer in if you want a stiffer embroidery. The tiles can be washed if you find any stabilizer residue remaining. You can add tiles if the embroidery is too big for one, the tiles interlock quite firmly, but can be easily dismantled once you are finished.

I usually insert pins at an angle to hold the lace but if you prefer your pins to be more perpendicular then use more than one layer of tiles, or pin the tile to another more permanent layer.

I also use them for blocking other sewn textile pieces, and they are great for knitted pieces.

They don’t fall apart like polystyrene packing, and they are light and easy to store or transport, and completely reusable.

Also for anyone having trouble removing stabilizer – always firmly pat the rinsed piece, while it is still wet, with absorbent paper – I use cheap blank newsprint but kitchen roll would probably work ok too.

Cindy Franseen

I’ve always felt that having ‘a signature style’ is for marketing purposes. If how you are wired is to work in different styles, then so be it…stay true to you. To me, that’s all that really matters.

Joan Hamilton

Amazing and beautiful. And a big shout out to the wonderful people from Textileartist.org for the work they do and the joy they give to people like me.

Jennifer Williams

She is an amazing artist and inspirational to the weekend warrior. Thankyou for sharing this beauty.

Arnab Saha

Nice design