When you look at Susie Vickery’s career, her travels and her textile art, you gain a sense of freedom, joy and vitality. What more could you ask of life?

Textiles alone can be fascinating enough – they offer texture, colour, expression and so many opportunities to indulge the senses. But Susie has added an extra dimension – automata, or moving mechanisms – which give stitch a whole new sphere of possibilities.

It’s clear that Susie loves to play. Her mind buzzes with ideas that keep her awake at night and she can hardly wait to put her new ideas into practice. When she combined her love of storytelling with the idea of making her puppets and installations move, she excitedly set to work.

Her life-sized, immersive, stitched seascape The Curious Five Go Surfing includes moving sharks, surfers and an ocean liner, while her finely crafted embroidery and audio-visual installation, Peregrinations of a Citizen Botanist, showcases her theatrical experience.

Got a spare moment? Then enter the mesmerising world of Susie Vickery and you can’t fail to be entertained.

Enthralled by embroidery

TextileArtist: What initially attracted you to textiles as a medium?

Susie Vickery: I have always sewn and made things since childhood and was lucky enough to turn those skills into a career. I spent 20 years working as a costume maker in Australia and in theatre in London, specialising in men’s 19th century dress. I lived in Thailand for a year, returned to London and then spent the next 20 years working on community art projects in Kathmandu and in Mumbai, India, also in Tibet, Myanmar, Mexico and Turkey, finally going back to Western Australia. Phew, too many moves.

After moving to Kathmandu I couldn’t carry on with costume making so I started working with local women’s handicraft groups to help them improve their quality and develop new designs. This led to an ongoing career of handicraft development, working with a variety of groups.

Shortly after arriving in Kathmandu, I went to an embroidery conference in India. My eyes were opened to a whole new world. I met practitioners, researchers, people working in development, historians and pure enthusiasts. I was so excited that I couldn’t sleep at night. I have continued to be amazed by the range of embroidery and its ability to enthral.

I then began a degree in embroidered textiles by distance learning and haven’t looked back. It still is my driving passion.

“I love all things to do with stitch. It is definitely my meditative practice.”

Susie Vickery, Textile artist

How did you develop your artistic skills?

My artistic skills came through my degree, which covered how to look at things and how to interpret them into stitched pieces. My technical skills have been built up over years but began with a base of tailoring skills from my costume making days where I specialised in men’s 18th and 19th century costumes.

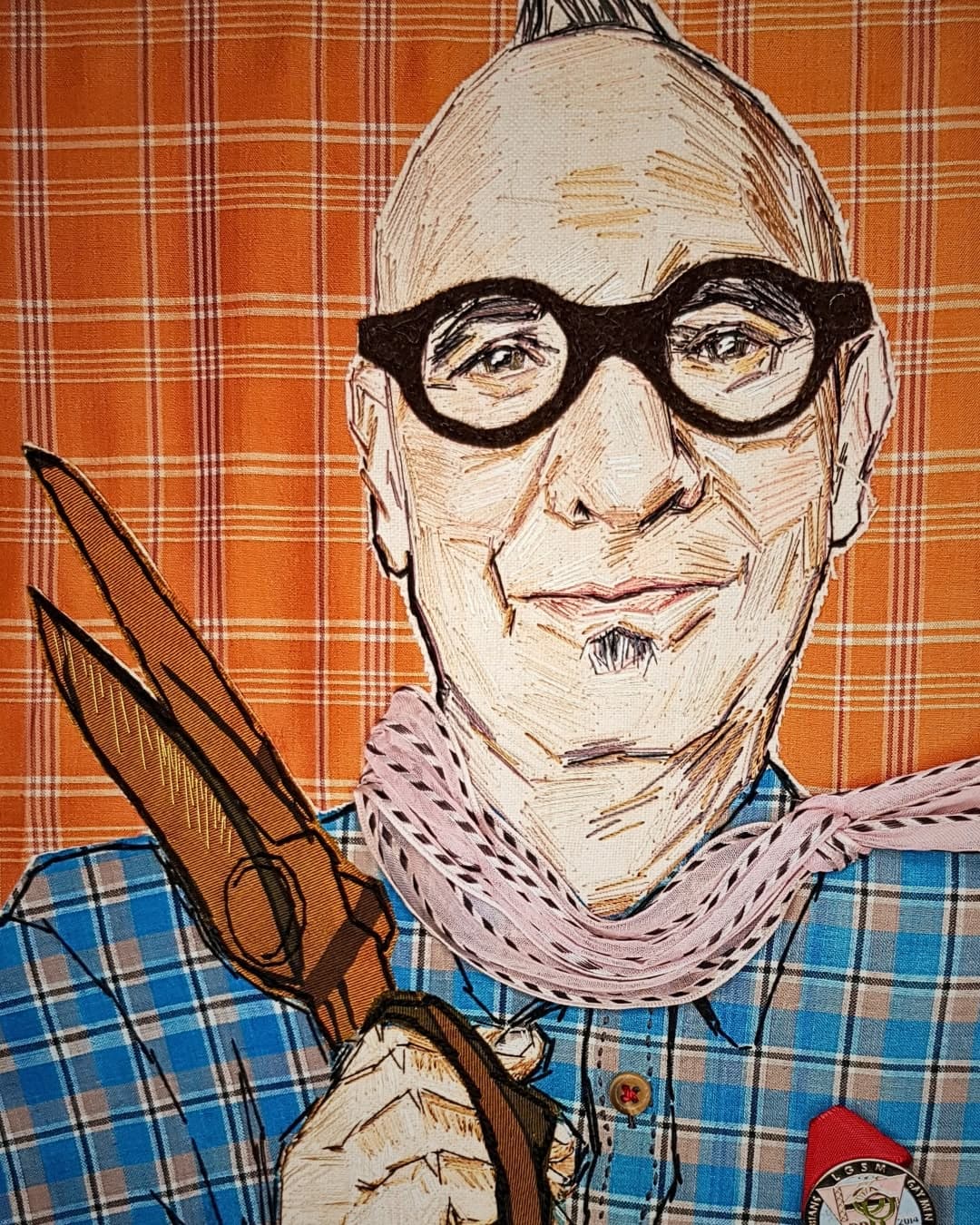

That is why buttonhole stitch is my favourite, and a lot of my puppets are edged with it.

But I am also heavily influenced by my surroundings and the people and issues that I am living amongst. When in Nepal I made a lot of little stitched and appliquéd portraits of the people in our small town on the Indian border, which I called Icons of the Ordinary. I was portraying them as equal to the ubiquitous images of the Hindu deities and the Bollywood filmstars.

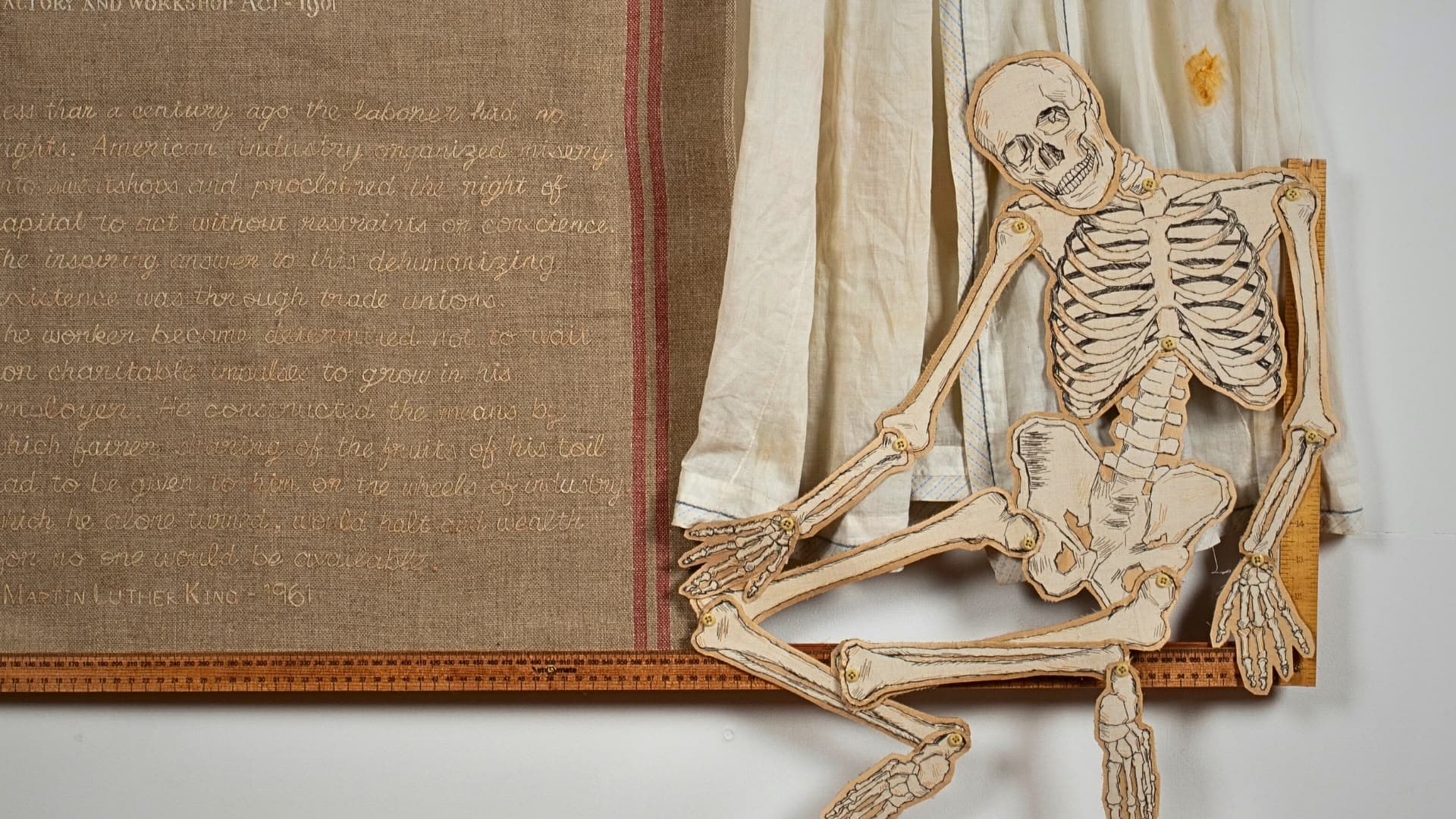

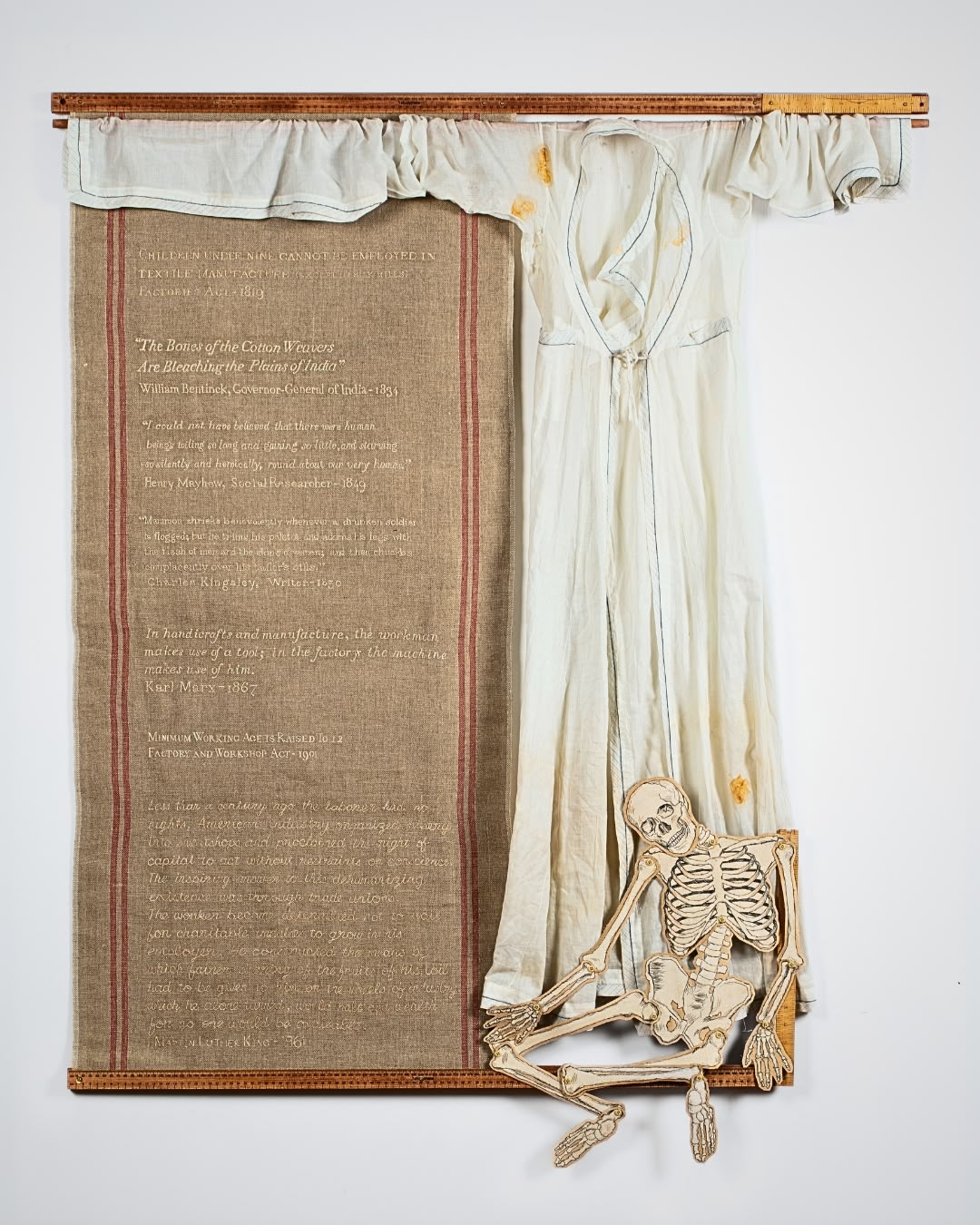

Then in Mumbai working with the marginalised people in the slums influenced my work. My dissertation for my degree was on sweatshops, so a lot of my work has been to do with the exploitation of workers, particularly in the garment industry.

After moving back to Australia I have become very concerned with environmental destruction, the loss of habitat and the extinction of species and of course, climate change. This to me is the most pressing issue, so most of my work lately has been addressing this.

Was there a particular turning point or key moment that influenced your art?

A few years ago, before moving back to Australia, I decided I was going to create what makes me happy. I love making toys, as in the Tibetan project, taking a two-dimensional image and working out how to transform it into three dimensions. And I wanted to get back to my costume making roots.

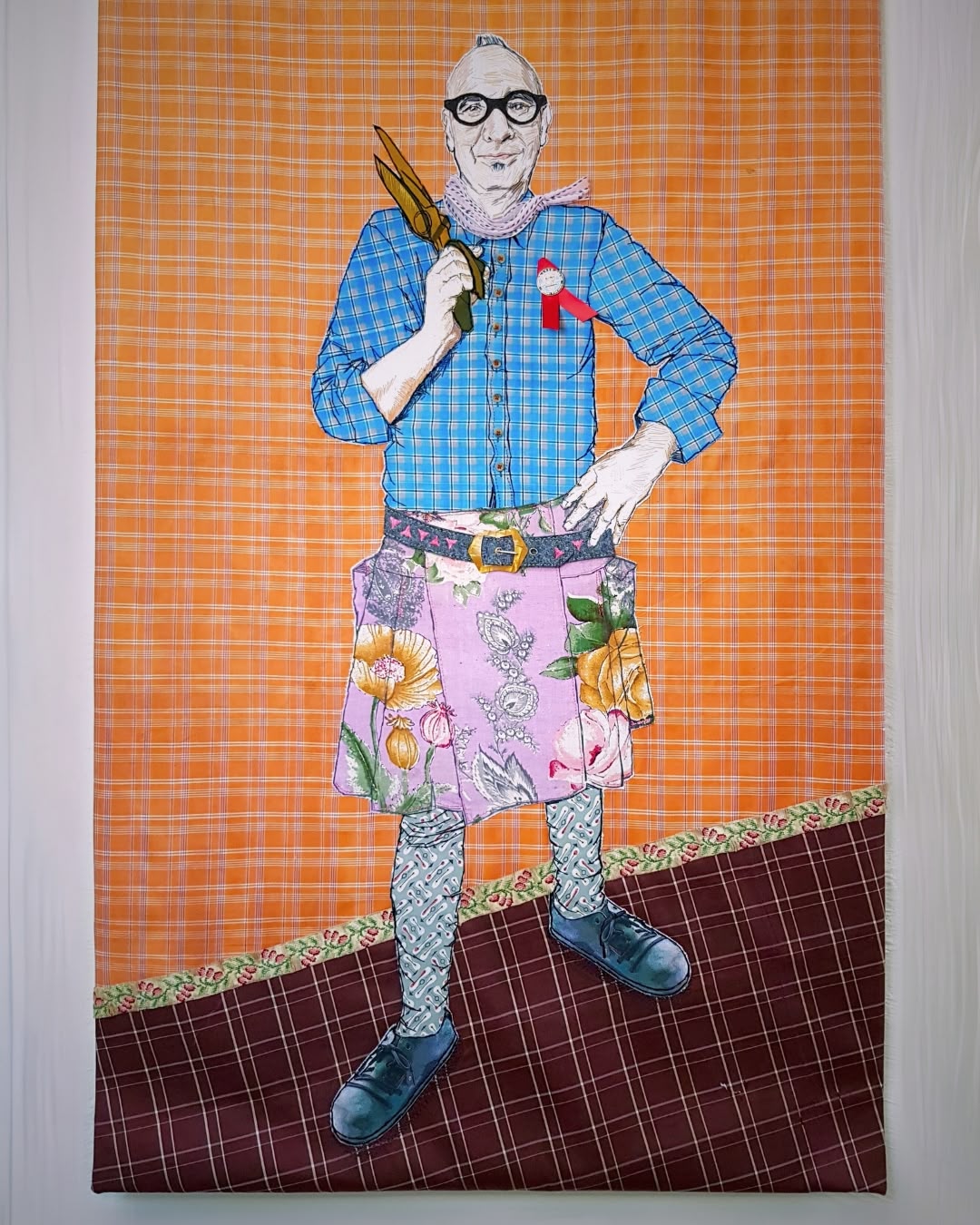

So I thought that I would make a puppet to travel with me. I wanted him to be 18th or 19th century, and to have come back to comment on the changes that we have wrought on the world. That’s how The Botanist came about. He travelled with me to the UK, Turkey, Nepal and India. Then he became part of my exhibition, Peregrinations of a Citizen Botanist, here in Western Australia. The idea is that he has come back to Australia, over 200 years after his first visit, and is taking a different approach, merging with the landscape instead of cataloguing it.

“The freedom given me by my decision to make what I really love doing – puppets, costumes, automata – has been very liberating.”

Susie Vickery, Textile artist

I was recently working on an exhibition idea with a friend. It was a great idea and fitted the theme of the exhibition and would have been fun to make. But then I realised, it’s not talking about the climate and there are no puppets, costumes, and crazy assemblages in it. So we rethought the idea to include those things and that made me feel much happier.

Storytelling research

Looking at the planning and research process, how do you develop ideas for your work?

My process is definitely more intuitive. I get an idea, then I experiment and play around. I do lots of samples, some drawings and lots of fiddling about.

I would love to say that I keep beautiful sketchbooks, but my medium is stitching; that is where I’m happiest. So I do rough drawings, collages and stitch experiments. I have boxes full of experiments. I get them out to inspire me when creating new projects.

Tell us about your process, from conception to creation.

It depends what the project is. My installation project The Curious Five Go Surfing for the Indian Ocean Triennial went through several iterations. I was given quite a large room so I wanted a walk through exhibition, like the cabinet of curiosities idea that I used in Peregrinations of a Citizen Botanist. It helps you to discover, to learn and to laugh. A lot of my work is historically based so the research is a really fun part of it.

I read quite a few biographies for The Curious Five Go Surfing as it was about five women who had crossed the Indian Ocean to transform their lives. I love working collaboratively as well, so I involved the women’s handicraft group that I had worked with for many years in Nepal and a friend in Kolkata who does indigo dyeing. We created an indigo ocean full of sea creatures, which was gradually becoming filled with plastic. The five women and their stories were included throughout the show. Plus, I made automata of endangered species of fish. The whale shark automaton needed a lot of sampling to get his shape and movement right.

I made lots of trial puppets for the automata and played around with finishes, decoration and edges. Just lots and lots of experiments.

All of the materials used were, where possible, recycled. The 50 metres of ocean was made of organic cotton printed with indigo and other natural dyes. And it was backed with denim from old jeans that I bought in charity shops. The whale shark was made of old jeans, and decorated with embroidery and old buttons. All of the automata were made from recycled timber, a lot of it picked up on the side of the road. It’s amazing how much old timber and furniture is thrown out.

All the puppets were made of old fabric from my stash, and the five women ended up surfing on bits of old plastic, bottles and shoes found on the beach. I think it’s always important that the materials that I use have a story as well. I can tell you where each piece came from, in my travels or given to me by a friend.

Automata & animation

What are you aiming to capture in your work?

I like storytelling and take a very literal approach to this. I like to put humour into my work, to make people think, and to inform.

The other important thing for me is the craft. I want my work to show technique. This comes from my tailoring background, I love to see well made work with dense stitching and skilled techniques. That isn’t to say that I don’t love people’s wilder, looser way of working, but I can’t work like that. I always end up doing things meticulously and neatly, maybe too obsessively.

I love to put movement into my work and have taught myself automata-making and stop-motion animation to use with my work. I want the viewer to interact with the work. My two recent solo exhibitions were both filled with handles to turn, drawers to open, pieces to read, and things to discover. They were like big, walk-through cabinets of curiosity. I have also, for years, been making stitched QR codes that lead to either my digital animations or further information. I like this combination of the hand stitched and the digital.

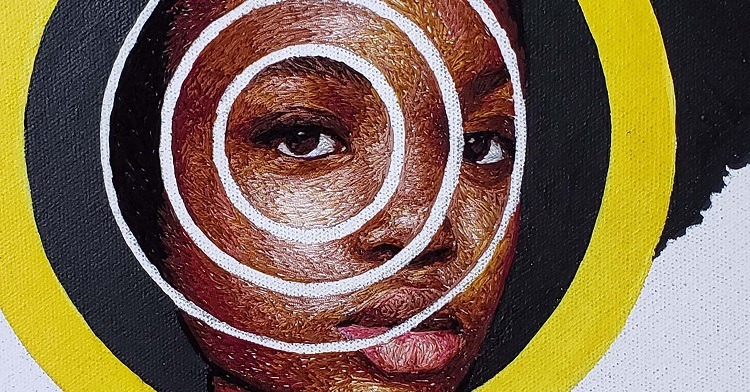

I love doing my stitched portraits but am always trying to push the style in different directions, working on a larger scale, doing single colour portraits, stitching from life, or making the image that I am working on three dimensional. Each portrait that I do is a new learning experience.

Simplicity & concentration

What are your biggest challenges in creating your art, and how do you overcome them?

Time time time, always time. I need time everyday to go for my swim in the ocean, to drink coffee, to spend time chatting with friends and neighbours and potter in the garden.

So maybe I need to ask someone for a few extra days a week. Plus, I get too many ideas, and have way too many ideas on the go at one time. So it’s all about focus, I need to really work on concentrating, not skipping around from project to project.

“I have realised that my experimentation can turn into a piece that I’m happy with in the end.

So experimenting is never wasted. It’s always leading to something.”

Susie Vickery, Textile artist

I always have some straightforward stitching for when I want to do a project in front of the TV and when I visit my mum. I keep the thinking for when I am alone, and save the simpler stitching that doesn’t need that level of focus for those other times. I can’t do the portraits unless I am on my own and concentrating.

I do find that in making new work, especially when a big exhibition is coming up, that the constant decision making is exhausting. So I am happy when I have made all the difficult decisions about a piece and can get on with the stitching.

What piece of equipment could you not do without?

It’s always been my thimble. I seem to have amassed quite a collection as I buy in bulk when I find the right ones. I am no longer going to Kathmandu where I used to buy them in a little hole-in-the-wall haberdashery shop. I wonder if he still has them…

The trouble that I have is that they all end up in one place. So I will have six here in Australia and none in London. I need to wear them around my neck perhaps! I do have a lovely necklace that is made of old brass thimbles.

I collect old tablecloths and napkins from charity shops, they’re a great base to work on. And jeans are just the best base with a strong and firm weave. I use them a lot. But you have to look out that you don’t pick up stretch jeans, which are much harder to sew into. It’s best to go into the men’s section of charity shops, their jeans are better quality and bigger.

What advice would you give to an aspiring textile artist?

Make what you love doing, not what you think other people will like. Then everything that you make is a true expression of you and has veracity. I always make exhibitions that I would like to go to. Go with your instinct, if you are happy with your work, it will be good.

Which direction do you think your work will take in the future?

There’ll be more automata, more storytelling and more ranting about politics. I have so much to learn about automata-making and so many ideas to put into practice. I want to do more costume related work.

I am currently beginning two new projects. One is about the wreck of a Dutch ship off the coast of Western Australia in the 1600s. There’ll be plenty of great puppet and costume opportunities in that. It’s about survival against all odds and looking after the weaker members of society, which I think applies to us now and in our near, potentially scary, future.

And the other is with the indigenous residents of a town outside Perth. We are working together to illustrate the journal of a settler in the 1860s. We are going to make lots of automata and puppets for that one. This exhibition will look at how we can learn from past mistakes and attitudes, but also how we can work together, equally, towards a better future.

2 comments

Suzie foote

I love the differences I see and the feelings it invokes.

Gina

Great information Thank you so much, I never thought I would be able to make a picture on fabric. This is wonderful. Thank you for inspiring me to inspire myself.