Throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, the Flanders region of Belgium functioned as the centre of European tapestry production, commended for their particularly large textile works filled to the brim with intricate, painstaking detail.

Flemish artist Sylvie Franquet is attuning herself with her own cultural roots.

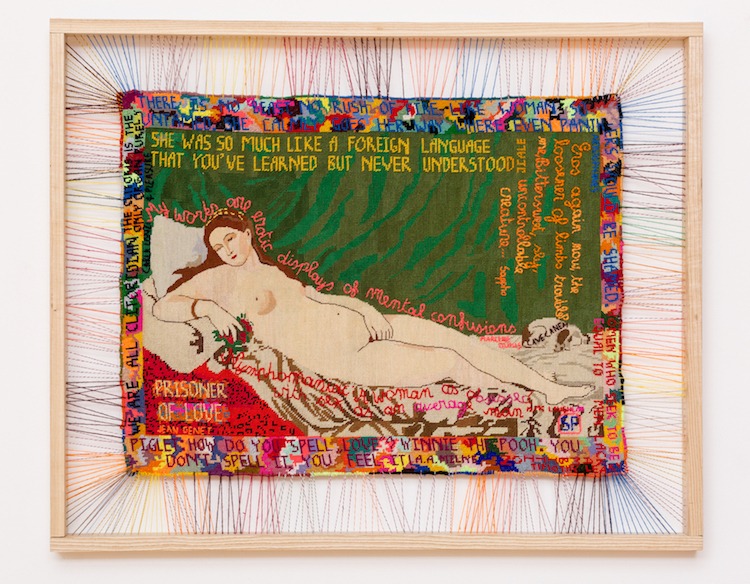

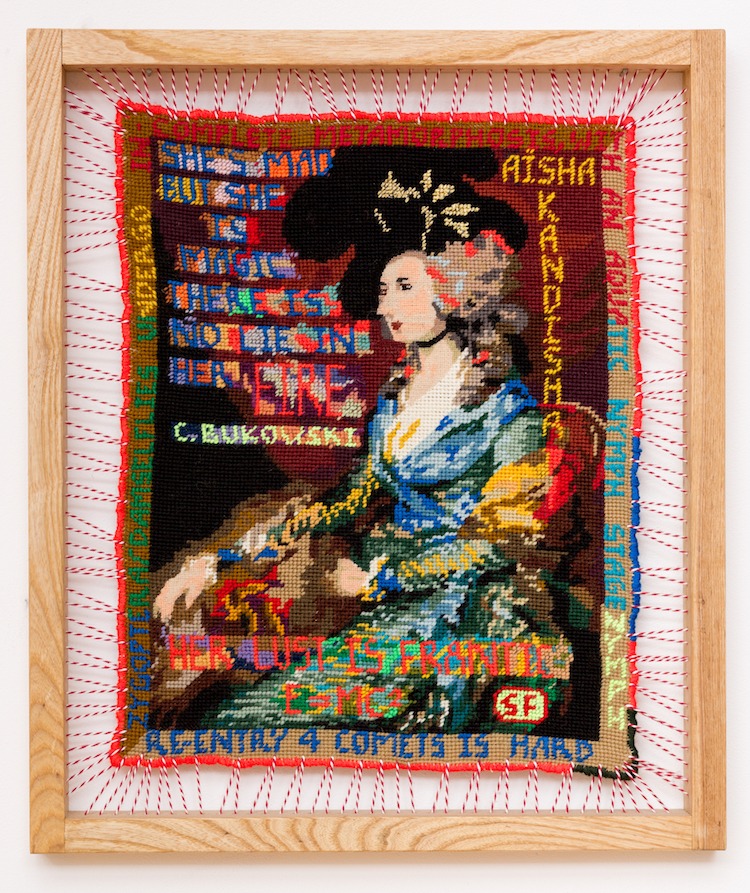

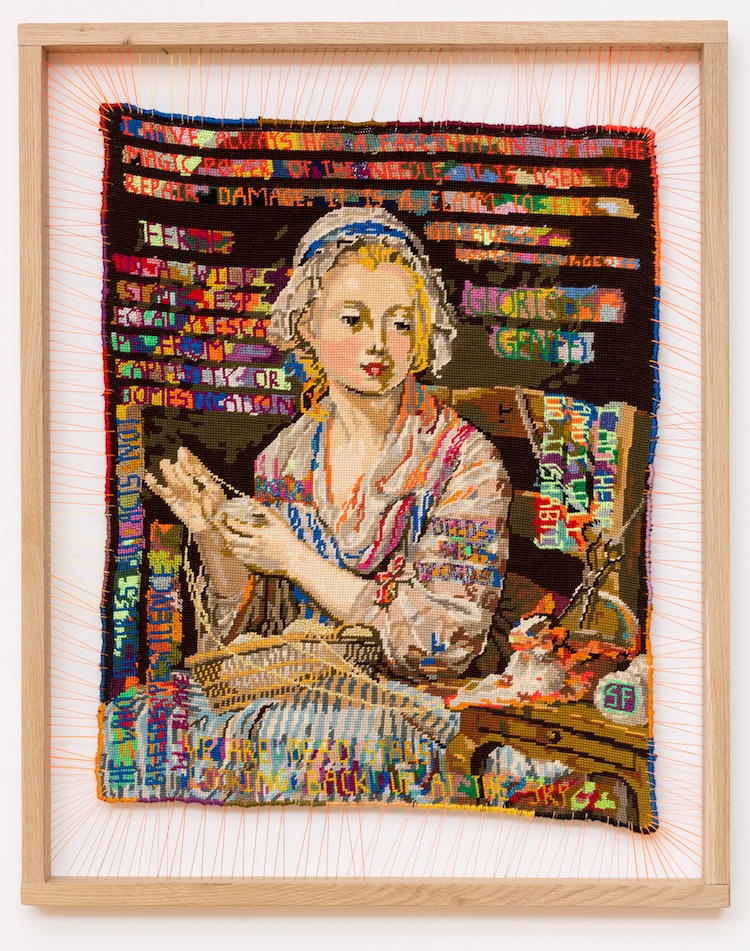

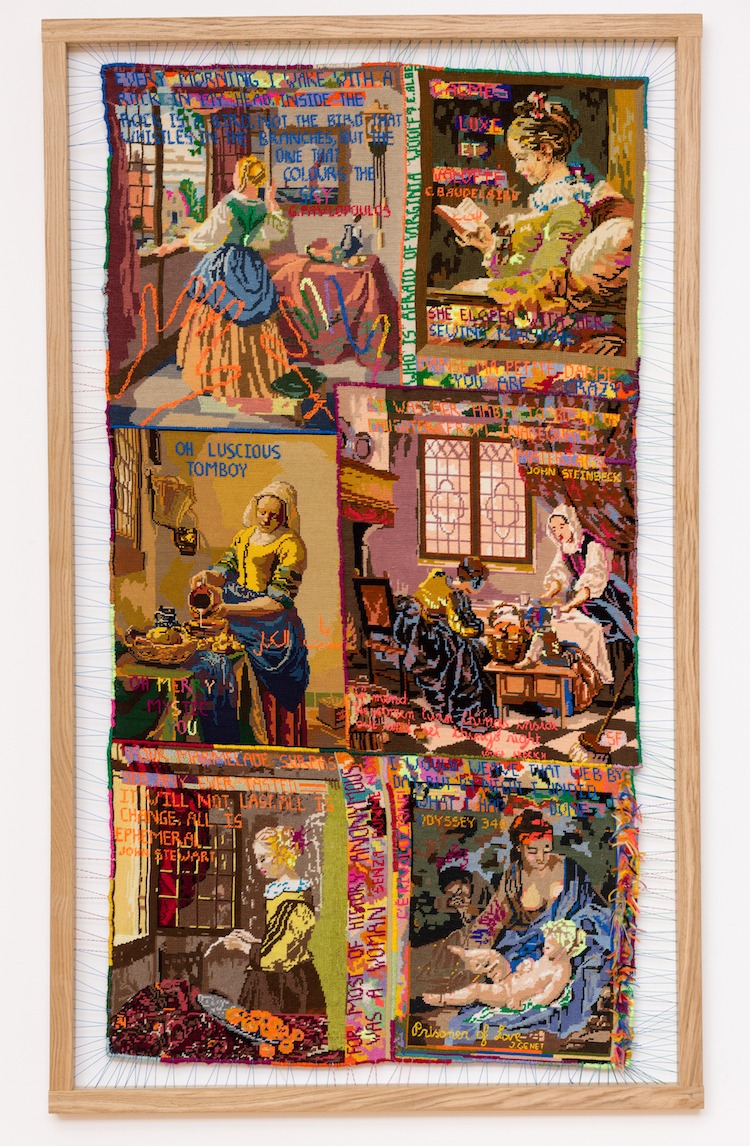

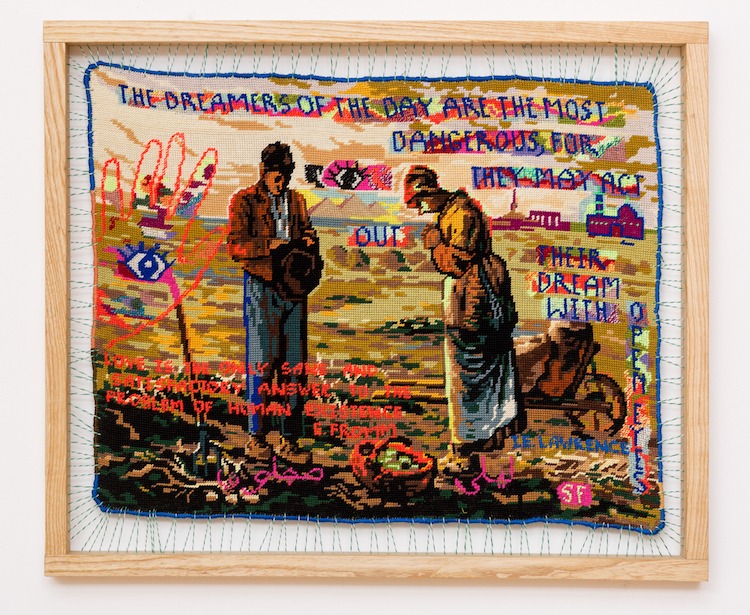

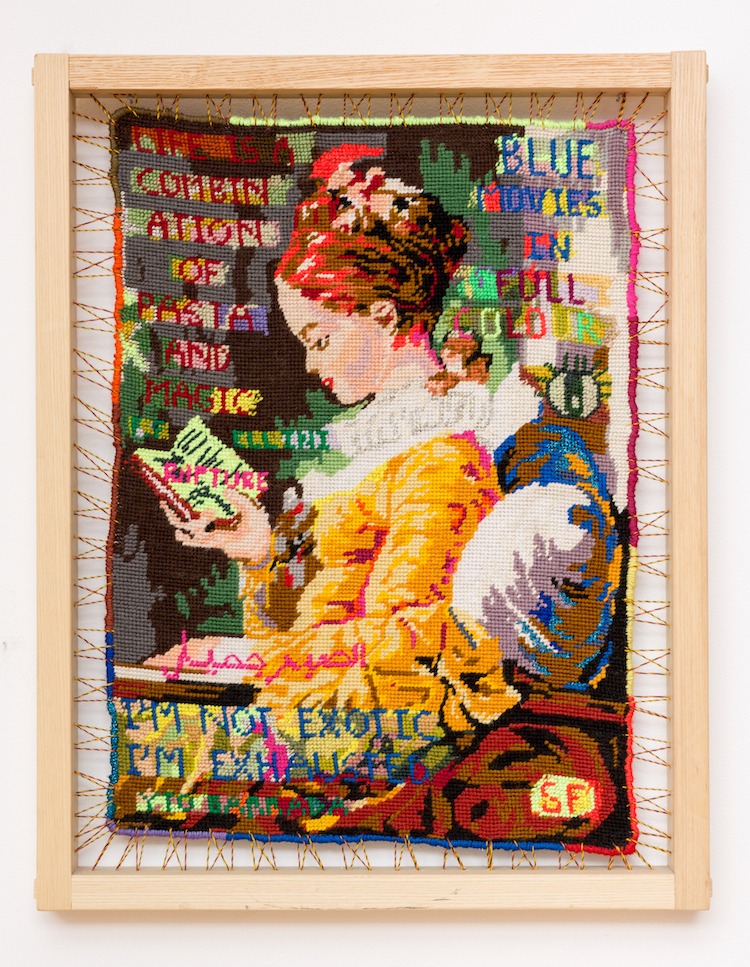

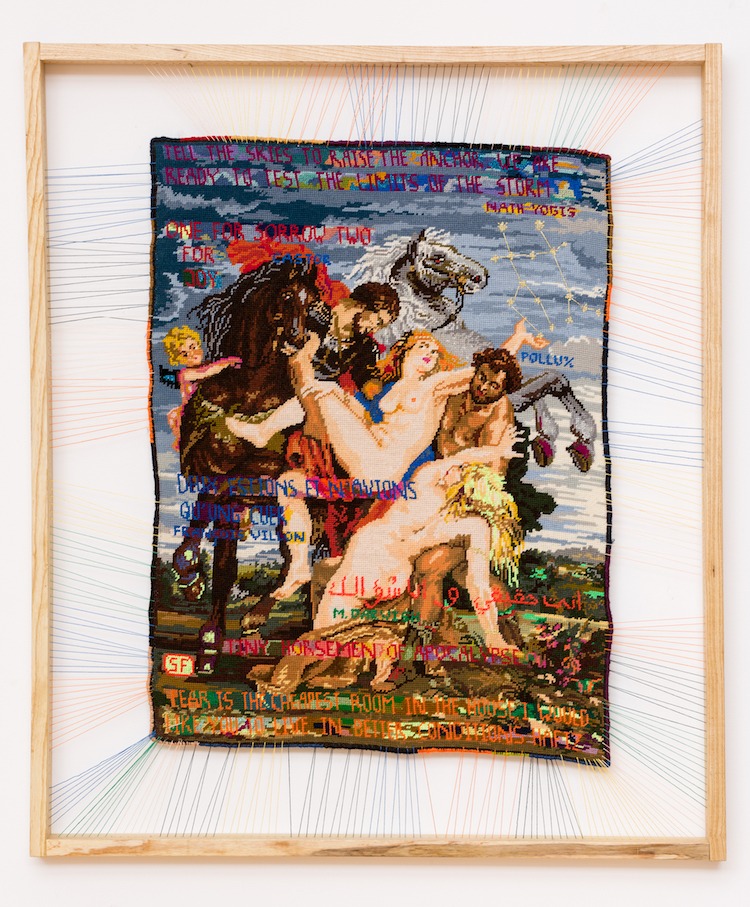

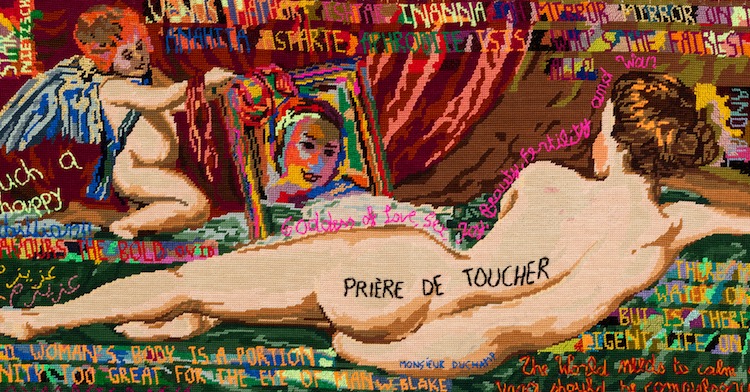

Franquet doesn’t create her tapestries from scratch; the artist builds upon her own cultural history as she reworks found tapestries with her own embroidered imagery and text.

Although her practice involves a certain degree of appropriation, the artist is particularly selective when it comes to finding her raw material, generally looking for tapestries adapting canonical art masterpieces, with a predilection for those that depict nude females.

In this interview, Sylvie gives an insight into her thought-provoking and humorous take on the world of the grand master. We learn what methods and techniques she prefers and how travelling often compels her to create.

Reworking found tapestries

TextileArtits.org: What initially attracted you to textiles as a medium?

Sylvie Franquet: I’m Belgian, and the country has a long tradition of textile production and textile art….woven tapestries etc. I have always made things in fabric, knitted and sewn my clothes.

However, this more recent story all started when I inherited a cupboard full of needle points when my mother-in-law died. I realised she had not entirely finished any of them. That intrigued me, it said something about her that I didn’t know. She always seemed so perfect. I had never been interested in needlepoint because I don’t like following a pattern, but I couldn’t throw these away.

I started filling in the blank holes she had left in the very traditional needlepoints of Victorian roses, with my own lurid colours, geometric patterns and words. I liked the result a great deal and found it an interesting way of working. Later on, I started reworking found tapestries, by unpicking and re-stitching them, embroidering on top.

And, more specifically, how was your imagination captured by stitch?

I sew on everything. I like darning, repairing almost as a decoration. The randomness of moth holes creates an intricate pattern for instance. I am interested in the way needlepoint somehow resembles digital pixelation…it’s so hard to do an accurate face in needlepoint portrait, it’s really like an impressionist technique.

I am also interested in the kitsch aspect of needlepoints, particularly of iconic masterpieces of art. I slowly developed my own voice while unpicking and sewing the works. I love the conceptual and subversive approach to something seen as a demure, domestic female expression. The laborious process in itself seems to me like a rebellion to our world where time is money.

A volcanic explosion

What or who were your early influences and how has your life influenced your work?

My mother made many of my clothes. Later I started making them. So I’ve always stitched, knitted and made accessories. I was a travel writer and collected fabrics and beads on my travels that I ‘collaged’ together when in the UK. My accessories traveled again around the world to the US, Japan, France, Italy etc.. and featured in fashion magazines like Vogue and Harpers.

I always made collages, mail art, even my written stories were collages. I traveled a lot in the Mediterranean and the Middle East, and that has been a huge influence on me. I’m fascinated by that part of the world, by ancient history, mythology, the beginnings of civilisation, the philosophy, the light, the colours, the stories.

I’m particularly fascinated by Islamic art, the way the calligraphy, the word, both has meaning and is part of a series of patterns. That is quite important in my work. My needlepoints are collaged stories of visual elements, colour and words.

What was your route to becoming an artist?

Mmm not so sure, many people say I always was one, it came out in different forms but was never intentionally concentrated as it is now. With the needlepoints, about six years ago, I suddenly felt I had found a way of using my hands, my humour, my love of reading and my mind all at the same time. I also found a way of expressing how I felt about the world, about being a woman.

I created the work on planes, buses and trains, as I travel a lot. My friend Duro Olowu displayed some of them at the exhibition More Material in New York, summer 2014. And they were a success, so then October Gallery, London decided to give me a show.

So it all kind of happened in the last 5 years. I never had any art school training, but I kind of like that. It has been a long time coming, and right now feels very much like a volcanic explosion.

Tell us a bit about your chosen techniques.

I work mainly in textile, but in fact, I like working with all kind of found materials. I make collages with paper, cut from art and fashion magazines, exploring female desire and often stitching on top.

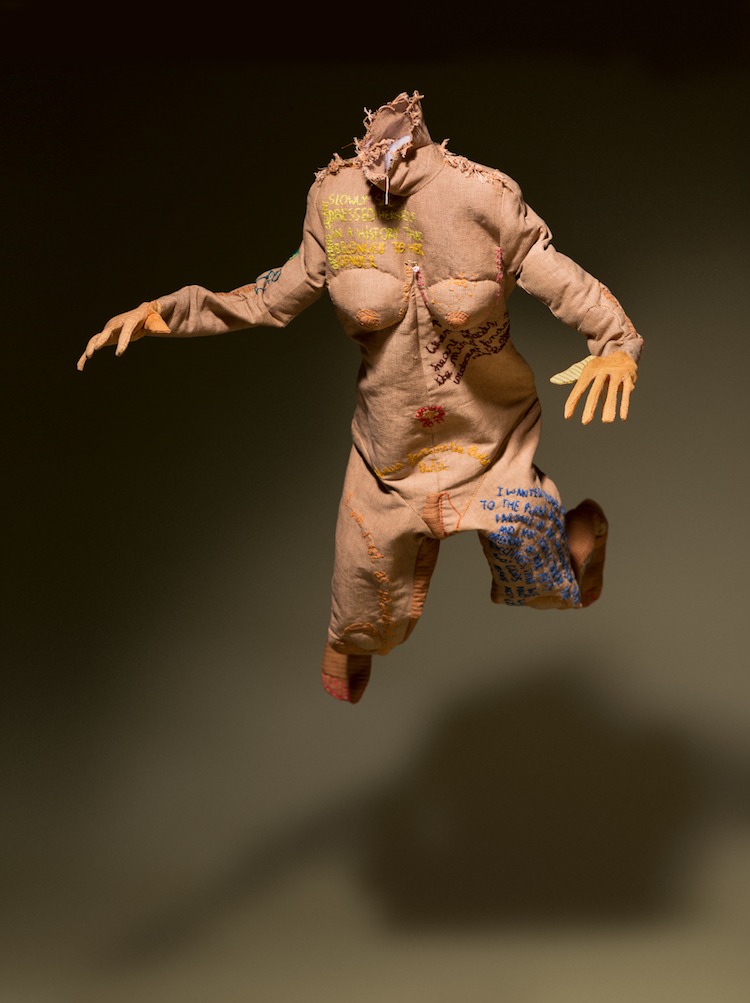

I work with found needlepoints, unpick some of them, re-stitch them, stitch and embroider poetry or text messages on top. I stitched poetry, philosophy and proverbs, on top of Egyptian ragdolls I had commissioned, as magical formulas for the living.

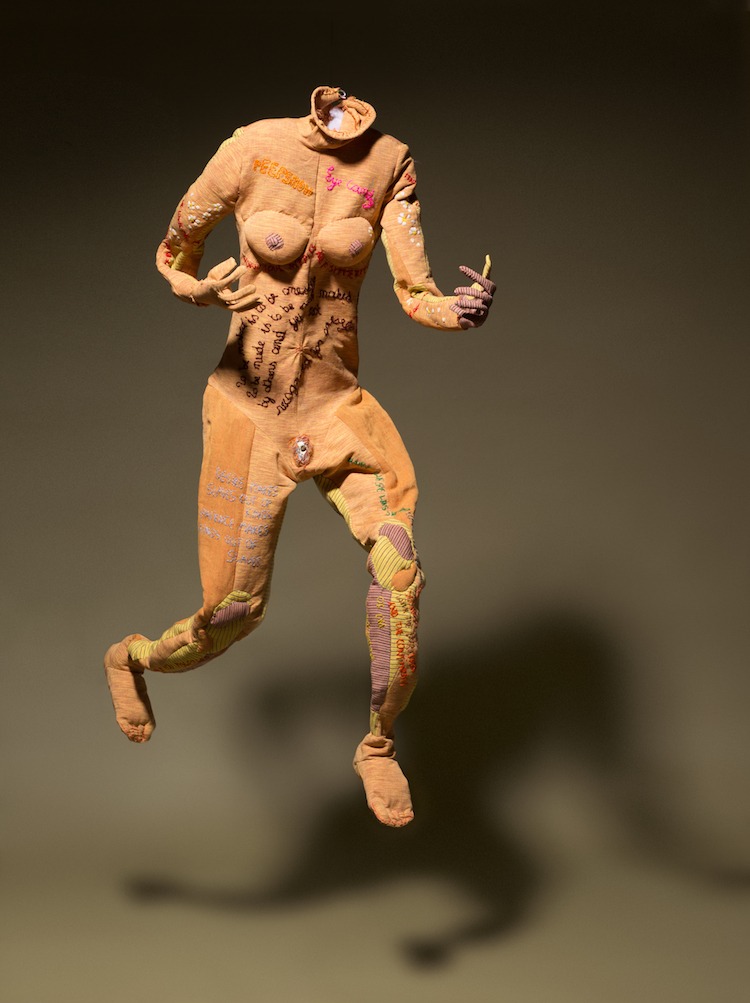

I had a pattern cut of my body and re-membered all the pieces into textile sculptures, again embroidered with words. But then I also made imaginary bird messengers from driftwood with feathers found on the beach.

How do you use these techniques in conjunction with embroidery?

I embroider words, texts, fragments on everything, my sculptures, my needlepoints and even on my paper collages. The bird messengers carry embroidered messages. To stitch the words is in some way like fixing them…As I said, I made a large installation of 99 Wayward Sisters, Egyptian ragdolls embroidered with wisdom from the past and the present.

I don’t like boxes

How would you describe your work and where do you think it fits within the sphere of contemporary art?

I’m not sure where it fits into contemporary art. It seems to be a little bit on its own. It fits in perhaps with feminist artists looking at the female voice, gaze, expression, on looking at gender questions in art history.

It questions art history, why are certain works masterpieces, and others not. It looks at how male masters portray female nudes, women in their space, and then somehow women doing a needlepoint of it fixes the image of themselves but seen by a man. It’s a form of accepting the roles given to them throughout history.

Stitching is both subservient and rebellious, I like that. Someone called my work both in and outsider art. I like that too. I don’t like boxes, I’m happy not to be put in one. Not yet!

Do you use a sketchbook? If not, what preparatory work do you do?

I use a notebook. I choose a worked needlepoint of a masterpiece and try to understand why the painter originally chose the image, why the person, often a woman, chose that image to stitch and why I have chosen it to work on.

Then I think of what it reminds me of and I slowly build up a story. Unpicking and re-stitching, like Penelope in Homer’s Odyssey, searching for some truth. I add the words to it, and the various layers form one story.

What environment do you like to work in?

A lot of the needlepoint I do while I am traveling, on planes, buses, trains, and in the car… I love that in a way. I can be chatting to who is sitting next to me, look at the landscape, somehow it is all reflected in the work.

I sort of sit both in the east and in the west. Of course, I am also inspired by Iranian rugmaking, particularly the symbols, I use rug wool….

Who have been your major influences and why?

I have always been interested in contemporary art.

Seeing the work of the Italian artist Alighiero Boetti at the Whitechapel in the late ‘90s really moved me. I loved his ideas, his woven and embroidered works, his humour.

Equally a few years back when I saw Louise Bourgeois’ textile works at Hauser and Wirth on Savile Row, I was enchanted, and for the first time ever I felt a complete feminine expression.

Also Rosemarie Trockel’s show at the Serpentine, Marlène Dumas at the Tate etc. There were so many influences. I adore Bourgeois’s saying ‘I have always been fascinated by the magic power of the needle. It repairs, it’s an act of forgiveness’….something like that, I feel the same.

Tell us about a piece of your work that holds particularly fond memories and why?

I like all my work because what I don’t like was never completed. I like the poupées, the life-size sculptures of a pattern cut from my body.

A friend measured me up, made a pattern and a toile which she fitted on me and adjusted. It was such a magical process. I took the pattern to Egypt, found Egyptian handwoven cotton from Akhmim and put it together bit by bit, by hand, and hung the various members on a washing line, and then slowly embroidered the words and put the pieces together. It did feel like shedding a skin, a layer a sort of metamorphosis.

What other resources do you use?

I read a lot, also blogs, websites, magazines etc.

What piece of equipment or tool could you not live without?

A needle and scissors

How do you go about choosing where to show your work?

So far other people have chosen to show my work. In that way, I am a complete outsider to the art world.

Where can readers see your work this year?

I don’t have a website, but I do have a Facebook page, Sylvie Franquet Tralala.

Several places are interested in displaying my work but nothing is fixed yet. My work is also on artsy via the October Gallery.

Also, I self-published a small book called ‘Sylvie Franquet’s Wayward Sisters’, featuring the 99 Egyptian dolls and their wisdom. This can be bought on October gallery website.

If you’ve enjoyed this interview why not share it with your friends on Facebook using the button below?

Comments